The Wanyan Digunai (Wanyan Zhong, Esikui) funerary complex in Primorye

Автор: Artemieva N.G.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.52, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article outlines the findings of studies of a funerary complex beside the stone sculpture of a bixi turtle, discovered in 1893 on the territory of the mill of O.V. Lindholm in Primorye. The present research is based on unpublished diaries (from 1893 and 1894) of F.F. Busse, who carried out rescue excavations of the hill under the sculpture and unearthed a stone coffin buried nearby. A rounded stele top with 20 Chinese characters was found at the same place. The translation demonstrates that the burial was that of a prominent Jurchen military leader belonging to a noble Wanyan clan— Wanyan Digunai (Chinese name Wanyan Zhong, 完颜忠 , known as Esikui/Asukui, 阿思魁 ). The burial was largely neglected, because scholars focused on translating and interpreting the inscription. The burial was believed to have been looted long ago, and Busse's diaries remained unpublished. The focus of the present study, therefore, is to describe all available sources relating to Wanyan Digunai's funerary complex. Based on the analysis of the excavation findings, features of the funerary rite are reconstructed. The architectural design and layout of the complex are shown to have followed the local East Asian tradition.

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146983

IDR: 145146983 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2024.52.1.089-098

Текст научной статьи The Wanyan Digunai (Wanyan Zhong, Esikui) funerary complex in Primorye

The medieval antiquities of the city of Ussuriysk represent the highlights of the history of the Russian Far East. Archaeological sites discovered there are of striking importance and highly informative with relation to issues concerning the history of East Asia. This territory includes the city of Kaiyuancheng (开元城, Krasnoyarovskoye fortified settlement)—the Upper capital of the Jurchen state of Eastern Xia (东夏国, Dongxiaguo); the city of Xupinlu (恤品路, South Ussuriysk fortified settlement)—a district center of the Jin Empire; as well as two funerary complexes with stone sculptures of turtles, which have provoked the interest of scholars since the 19th century. They are referred to as the Ussuriysk and Khabarovsk turtles according to the current locations of the statues. The former is presently associated with the founder of the Eastern Xia state, Puxian Wannu (蒲鲜万奴) (Artemieva, 2019), while the latter is associated with the outstanding military leader from the famous Wanyan family, Wanyan Digunai (完颜迪古乃, Chinese name Wanyan Zhong (完颜忠), nickname Esikui/ Asikui (阿思魁)) (Larichev, 1966a: 235–237; 1966b, 1974). Scholars have usually paid more attention to the grave stone structures than to the burials. The objective of this study is to present evidence from the unpublished diaries of F.F. Busse who excavated the burial mound with the Khabarovsk turtle in 1893 and 1894, reconstruct the funerary rite using sources related to the burial of Wanyan Digunai, and identify specific features of spatial distribution and architecture at the Jin family cemeteries.

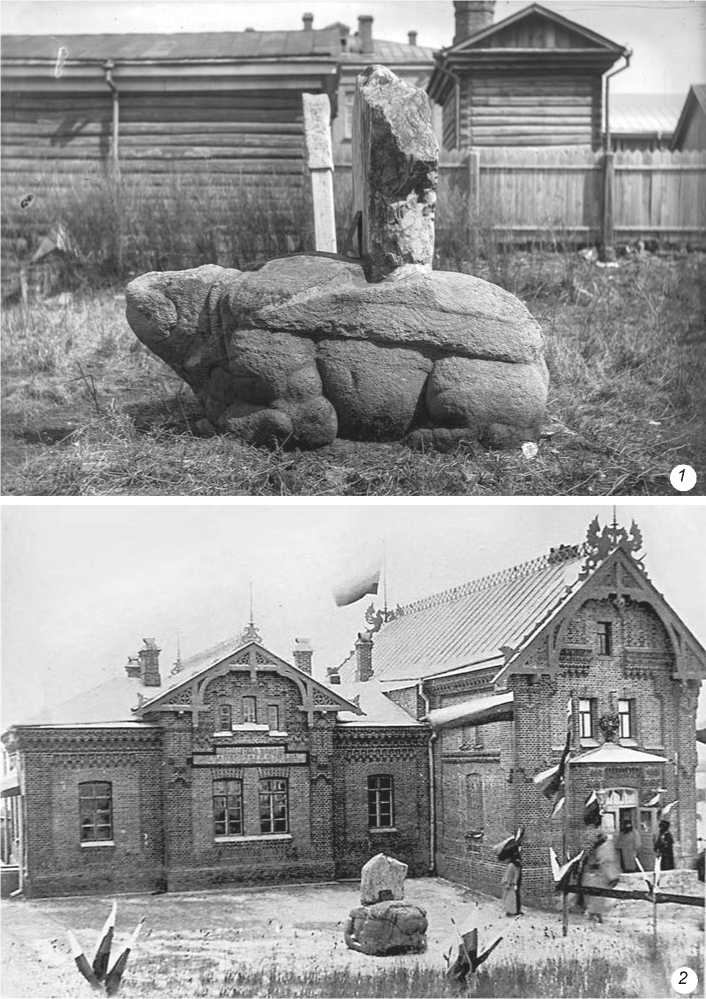

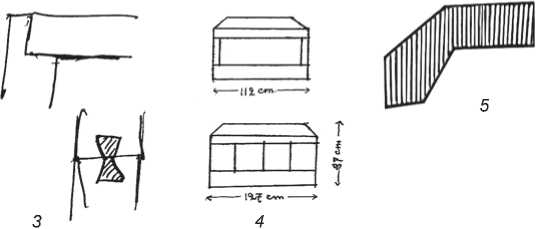

The Khabarovsk stone turtle (Fig. 1, 1 ) is located in front of the entrance to the Grodekov Khabarovsk

Fig. 1 . Turtle at O.V. Lindholm’s mill in 1893 ( 1 ) and in front of the building of the Amur Department of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society (Khabarovsk) in 1894 ( 2 ). Photo from the collection of the Grodekov Khabarovsk Regional Museum .

Museum of Local History (Fig. 1, 2). This gravestone was first discovered by F.F. Busse, who visited the village of Nikolskoye in 1866: “…I saw two statues of turtles, a grave decorated with three pairs of statues of rams, people, and columns” (1893a: fol. 48). Initially, its discovery was attributed to P. Kafarov, who visited Nikolskoye in 1871 (Kafarov, 1871; Khokhlov, 1979). He made a drawing of the burial ground with the Khabarovsk turtle and placed it on the main drawing of the “Plan of Dvugradye and its environs”. The funerary complex was depicted schematically as an embankment line, marked by six burial mounds. Dots indicated four more burial mounds inside this approximate geometric figure (Fig. 2, 4)*. Kafarov was the first to describe a rounded stone top with an inscription written in Chinese characters and associated this text with a person “from the most noble Jurchen families”, who lived in the early 13th century (1871: 94).

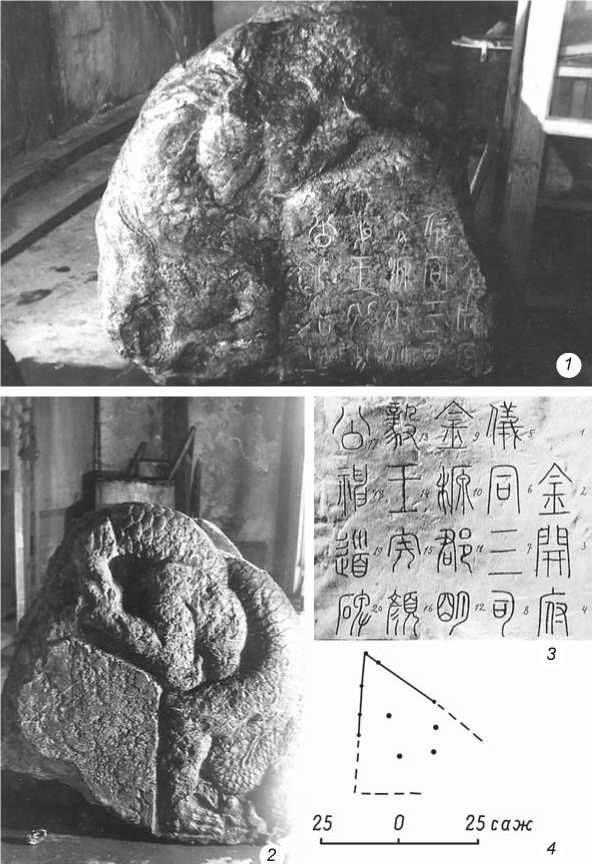

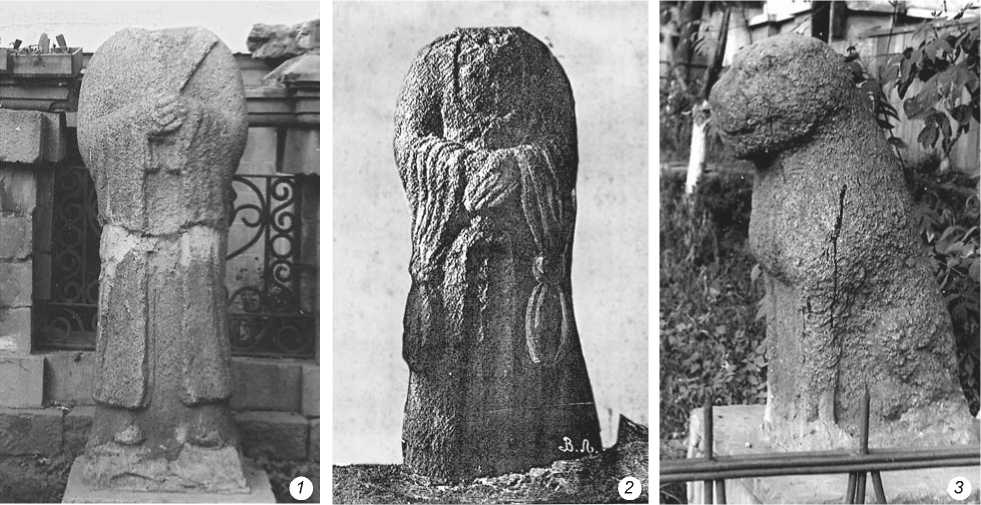

Fig. 2 . Top of the stele with a dragon image. 1 – front side; 2 – reverse side; 3 – trace drawing of the inscription on the top (Busse, 1893a: fol. 53); 4 – diagram of the funerary complex made by P. Kafarov (Busse, Kropotkin, 1908).

The top, which formed the upper part of a funeral stone, was subsequently lost. It was rediscovered in 1885 by V.S. Mikhailovsky in the yard of the peasant Spiridon Nazarenko. A part of the stone on the right side was chipped, but the front side retained twenty Chinese characters, four lines of five characters each. One sign was lacking (Fig. 2, 1–3 ). Presumably, it was the character 大 (da, ‘big, great’), which was part of the name of the Jin state 大金 (Da Jin, ‘Great Jin’). The surviving (complete) text was as follows: 大金开府仪同三司金 源郡明毅王完颜公神道碑 (Da Jin kaifu yitongsansi jinyuan jun ming yi wang Wanyan Gong shendao bei, ‘a stele on the way to the grave of the enlightened and resolute Jin revered prince of the Golden Empire [with the title of] kaifu yitongsansi Wanyan Gong’*).

Busse traced this inscription and ordered photographic copies from the Schulz workshop. These photographs were sent for interpretation to the Academician V.P. Vasiliev, to the Beijing Mission, the Chinese commissioner from the border commission, and to the archaeologist Wu Dacheng. Busse also gave many copies to sinologists in China and Russia. M.G. Shevelev was the first to translate the

inscription: “The monument… to the Prince of Wanyan Ming of the Great Jin Dynasty, the founder of the local government identical to the three chambers of the city of Jinyuan” (Busse, 1893a: fol. 53). Mikhailovsky, who was working on his translation at the same time, using a large number of sources, commented in detail on his interpretation of each character (“The monument of glorious merits, the Most Serene Prince of Jinyuanjun of Wanyan Gong of the Great Jin Kingdom”) and came to the conclusion that “everything occurred under Emperor Shizong, whose reign lasted from 1168 to 1190 AD” (Pismo…, 1890). V.K. Arseniev gave another interpretation: “A funerary monument of the 12th century was erected to the Commander-in-Chief of the Jin Army, the Jinyuan Prince of Wanyan” (1947: 303).

Orientalists of the 19th–20th centuries did significant work on the translation, but the final point in resolving this issue was made by Larichev, who proved that this burial belonged to Wanyan Digunai, the prominent Jurchen military leader from the Wanyan clan (1964, 1966a: 228– 229, 1966b, 1974). He was an important historical figure contributing to consolidation of state power in the Suifen River valley. Much later, without disputing the identity of the buried, Chinese scholars clarified the translation of the passage from the Jin Shi (“The History of Jin”) made by Larichev (Lin Yun, 1992: 37). According to the Jin Shi, Wanyan Digunai (Esikui) governed on the Suifen River for 13 years and died in the 14th year after the beginning of the reign of Xizong (Wanyan Hela, Chinese name Wanyan Dan, temple name Xizon; 1135), that is, the year of his death was 1148, as indicated by Larichev. The same chronicle also reported that in the 2nd year of Tiande (1150), people began to perform the ritual of sacrifice to Wanyan Digunai in the Taizong Temple, and in the 2nd year of the Dading era (1191), he received the posthumous title of “Jinyuan junwang” (‘Jin Revered

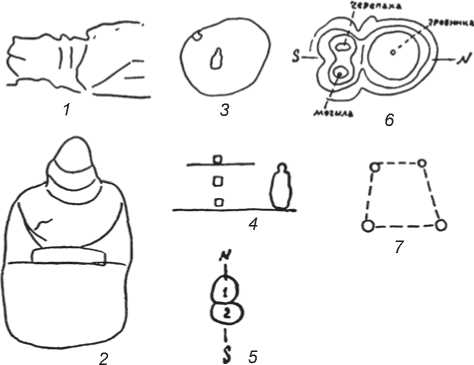

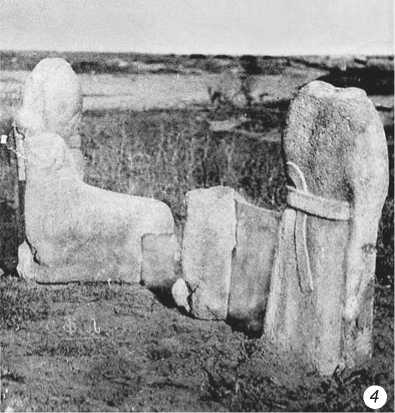

Fig. 3 . Drawings by Busse, from his excavation diary. 1–3 – stone turtle: side view, top view, and location on the hill; 4 – stone bases of columns located next to the statue of the turtle; 5 – diagram of the hills (1 – location of the stone coffin, 2 – location of the turtle statue); 6 – diagram of the hills after excavations; 7 – plan view of the pillars discovered in the burial mound adjacent to the stone turtle.

Prince’) (Jin Shi, 1970: 547)*. Based on this information, Wanyan Digunai (Esikui) died in 1148, and the funerary complex was built after 1191, because the inscription on the top of the stele contained his posthumous title.

According to the chronicles, Wanyan Digunai (Esikui) was one of the three sons of Wanyan Zhilihai, the leader of the Yelan tribe. The section of biographies of the Jin Shi preserved a brief biography of the commander, from which it follows that in 1118, after the death of Shitumen, the leader of the Wanyan tribe in the Yelan Province, he was replaced by his brother Wanyan Diguai (Esikui). The latter was a prominent commander and advisor to Aguda. At a meeting concerning war with Liao, Wanyan Digunai persuaded the Emperor to take military action in which he also took part. The death of Shitumen compelled him to return to Yelan. Wanyan Digunai organized resettlement of his tribe to the Suifen (Razdolnaya) River, since their old lands had become infertile, and lived there for thirty years, diligently engaged in arable farming (Larichev, 1964).

Lin Yun studied the biography of Wanyan Digunai and noted two important events related to him. From the first half of the 11th to the early 12th century, Aguda’s ancestors paid great attention to the Suifen River basin. The Jurchens had to use military force several times, because local tribes still possessed some independence— sometimes they served and sometimes they rebelled. The Jin dynasty firmly established its dominance over the region after the troops under the leadership of Wanyan

Digunai settled on the Suifen River in 1124, and there were no more military clashes in the entire Lindong region (literally, ‘east of the ridge’). Another event involved a report that Wanyan Digunai, together with Wanyan Loushi, submitted to the Emperor after the capture of Xianzhou in 1117, proposing “to resettle the poor to the interior lands” (meaning the conquered people). During implementation of this initiative, additional measures were taken to “provide material assistance to starving and poor people by the officials”, which contributed to independent influx of population from the Liao state. Then in the 7th year of Tianfu (1123), “people of all tribes moved to Lindong”, and in the 2nd year of Tianhui (1124), they were also given material assistance. This played an important role in further development of the Primorye region east of the Laoyeli Ridge. Regarding the time when the burial stele of Wanyan Digunai (Esikui) was set up, Lin Yun believed that this occurred in the 8th year of Dading (1168) (Lin Yun, 1992: 37).

Excavations of the Khabarovsk stone turtle by F.F. Busse in 1893–1894

Busse began excavating the hill under the stone turtle in October 1893. This was caused by the need of the owner of the mill, O.V. Lindholm, to use the part of the yard where the mounds were located for expanding his farm. It was decided to transport the statue to the public garden in the village of Nikolskoye and initiate excavations. Busse already had experience in that kind of work (Artemieva, 2019). It was planned to put the monument on a sleigh and transport it in the winter.

Lindholdm’s mill was located on the edge of a natural terrace on the left bank of the Krestyanka River, 1 km downstream from the Western Ussuriysk fortified settlement. According to the description by Busse, the statue of the turtle was located on an ellipsoidal mound, not in its center, but to the west of the highest point (Fig. 3, 3 ) (1893a: fol. 48). Another partially destroyed burial mound was adjacent to that mound (Fig. 3 , 5 ).

Busse kept a detailed diary of the excavations, which is now the only source of information about this burial (1893a). An excavation ditch, approximately 2.15 m long and 1.5 m deep on its eastern side, was made under the turtle statue along east-west line. A continuous layer of gray tiles of two types was under the sod (3–4 cm). Three stone bases of columns were found at a distance of 4.2 m on the eastern side of the turtle statue (Fig. 3, 4 ). Next to them, an iron chisel and a carnelian ornament with images of berries were discovered. A layer of clay with significant accumulations of large pebbles (15 cm) was under the tiles.

Another trench was needed for placing the sleigh under the statue. It was made along the meridian through the center of the adjacent burial mound. Many pig (?) bones were discovered under a layer of black soil (30–60 cm) at a depth of about 1 m northeast of the center of the hill, and bones of a large animal were found 30 cm lower. Both groups of finds were located in compact accumulations continuing into the eastern and western sides of the ditch, so Busse decided to begin excavations of the entire central part of the burial mound. The works were carried out in two sections. Two accumulations of bird bones were discovered at a depth of 1.2 m in the western part of the well. Blue bricks and fragments of tiles of various colors and sizes, which could not be correlated with any structure, occurred in the filling throughout the entire layer. Most likely, they ended up in the layer by accident.

An iron pipe 10.5 cm long with thick walls and a cap, and the fragment of a screw, attributed to the modern period, was found at a depth of about 1 m, which led scholars to the conclusion that earlier robbers tried to plunder the burial mound by digging a well in the center, which was later filled in. The robbers’ pit did not touch the full skeleton of a horse no more than 6 years of age, as was determined by the doctor F.F. Sushinsky on the basis of its teeth (Ibid.: fol. 50). A board located obliquely along the northwest-southeast line was below this skeleton at a depth of 30 cm. It was inserted into the robbers’ pit, and its lower edge rested against the stone that turned out to be the lid of the coffin. There was the skeleton of a dog in the middle part of the burial mound.

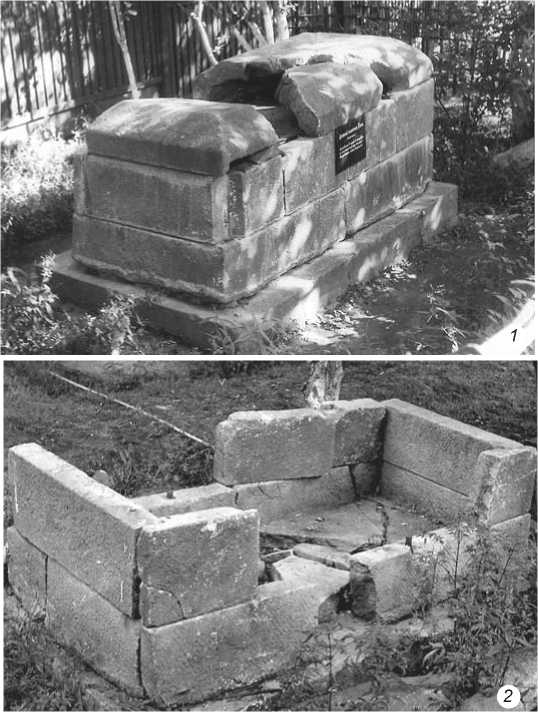

A stone tomb 2.3 m long and 1.5 m high, oriented with its long axis to the NW-SE, was unearthed at a depth of about 2.5 m from the top of the burial mound. The lid was broken in the center. A subtriangular hole measured ca 60 × 15 cm (Fig. 4, 1). Through this hole, soil collapsed into the coffin, and its upper part was filled with a mixed layer containing fragments of tiles, bones, and pieces of charcoal. Below, there were fragments of bones with traces of fire, a part of a human jaw with molars, iron arrowheads, a fragment of a lid decoration with a dragon’s head, and grains of a plant (Ibid.: fol. 51). A part of a human jaw was found above the lid, and another molar was discovered separately. These human remains might have ended up there when robbers tried to pull out the contents of the coffin through the hole. After seeing the cremated remains, they probably lost interest in the tomb.

Busse described the stone coffin in detail: “After clearing the tomb cavity, it turned out that the internal cavity was somewhat expanded to the west-southwest, and the width was 2 ft 9 inches (83.5 cm – N.G.A. ) there. I measured the ends to the east-northeast; it was 2 ft 6

Fig. 4 . Stone tomb.

1 – the tomb assembled, when it was exhibited near the Arseniev Museum of Local History (Vladivostok); 2 – the tomb without its lid (iron pins visible in the side slabs); 3 – diagrams of the fastening of the slabs, from the diary of Busse;

4 – drawing of the tomb (Busse, Kropotkin, 1908); 5 – profile of the tomb lid, from the diary of Busse.

inches long (61.1 cm). The length of the grave inside the walls was 6 ft 8 in (183 cm). The thickness of the vertical walls was 5 in (10.25 cm). The grave depth was 23 in (57.5 cm). The walls were made of properly hewn and well-preserved slabs laid on lime, which also connected the walls with the covering stones. Each of the two walls to the west-southwest and east-northeast consisted of one slab, while the long walls consisted of two layers: one full-length stone on the bottom and four stones on top. The bottom of each wall was made of one slab along its entire length” (Ibid.: fol. 51). After unearthing the layer located below the second layer of stones, it turned out that the corners were secured by soil pressure from the outside (Fig. 4, 2). At the top, all the slabs were fastened with iron brackets. Each of them was placed on an iron pin as a “butterfly” (Fig. 4, 3) fixed in the slab of the lower layer. Busse observed that “this fastening holds excellently, and it took considerable effort to knock out the brackets and remove the slabs. Pure lime is visible along the seams” (Ibid.: fol. 52). The bottom of the tomb was a monolithic slab with vertical side edges (Fig. 4, 4). The tomb was placed on four flat stones. There was empty space under the middle part, which was the reason for the tomb’s breakage under the pressure of the mass of soil of the mound. Large stones were tightly placed around the lower stone layer of the tomb, and were also located underneath the tomb.

To transport the stone turtle, an additional wide trench was dug, where charcoal, pig bones, and fragments of tiles were discovered approximately 3 m from the statue, indicating another grave. It was located in a burial mound to the east of the stone turtle (Fig. 3, 6 ). Excavations of that burial mound were planned for the next year.

A year later it turned out that Lindholm had organized the mill yard and leveled all the mounds (Busse, 1894: fol. 44). Therefore, before starting to excavate the new grave, it was necessary to establish the exact location where the stone turtle had stood. The location of the grave pit was determined by a layer of clay with charcoal, and fragments of tiles and bones. Yellow clay, found in the ditch, indicated the grave boundaries. After expanding the ditch to the north, Busse dug a pit 2 × 2 m in size and ca 70 cm deep. There were bones, tiles, and charcoal in the soil. At the bottom of the pit, there were six round black spots, consisting of decomposed wood remains (holes from posts). These formed a subtrapezoidal figure in plan view (2.1 m on the western side, 1.2 m on the northern side, 2.2 m on the eastern side, and 1.8 m on the southern side) (Ibid.) (see Fig. 3, 7 ). A pile of pebbles with an admixture of yellow clay was lower, and a layer of bones, charcoal, and soot (1.3 m thick) was under the pebbles. Widening the pit and the space near the other walls of the pit did not bring any new results. Busse concluded that “a small shrine ( miao ), covered with tiles and decorated with patterned clay shields, stood on the burial mound to the east of the turtle in ancient times. This is confirmed both by the objects discovered in 1893 and by the traces of posts in the clay, which were found now. The ground was disturbed under this miao , as can be seen from the charcoal and bones discovered during the current excavation, but all these traces of human activities are so unclear, so uncertain that now there is no way to guess as to the purpose which the ancient inhabitants had when building the burial mound under discussion” (Ibid.: fol. 46).

Upon reconstructing the remains of the second burial from the description by Busse, it can be inferred that the platform where the stone turtle stood was located at the place of an earlier grave. A number of column bases were discovered 4 m to the east of the statue, under a layer of tiles. The grave spot recorded on the sterile soil was located at a distance of 3.2 m from the stone turtle (under the bases of the columns). Its area was 4.5 m2. Most likely, a burial pit filled with cremated remains had previously existed under the platform on which the gazebo ( miao ) was built. This pit was covered with stones, and some kind of structure was built on top of it.

Busse mentions that the turtle sculpture was made of coarse-grained pink granite. A note to the report of 1893 provides an explanation: such granite, according to the mining engineer D.L. Ivanov can be found near the village of Nikolskoye in two locations: the cliffy bank of the Tudagou (Rakovka) River slightly above the railway station, and Mount Saltnikovaya on the Olenevka River near the village of Krasnoyarovskaya, on the southern side parallel to the mountain spur (the right bank of the Suifen River), where an ancient Chinese town (Krasnoyarovskoye fortified settlement) was located. The measurements of the stone turtle are also given: the width along the middle of the body – 4 ft 8 in (146.3 cm), the width along the same line from the vertical slab to the edge on the eastern side where the slab was broken off – 1 ft (30.4 cm), the width from the western side – 1 ft 2 in (36.5 cm), the length from the vertical slab to the rear end of the turtle – 2 ft 8 ½ in (85.3 cm), and the length to the beginning of the first neck fold – 1 ft 8 in (54.9 cm), the width of this fold – 6 in (15 cm), the width of the second fold – 5 ½ in (13.7 cm), the length of the head to the nose – 1 ft 9 in (57.9 cm), and the length of the entire turtle – 7 ft 9 in (240.8 cm) (Busse, 1893a: fol. 53).

The vertical slab that was placed upon the stone turtle was made of slate. It suffered greatly over time. Its outer layer disintegrated over the entire surface; therefore, the characters, except for two located in the upper right corner, were not preserved.

After the excavations, the turtle statue was installed in the public garden. In 1895, it was moved to the railway station of the village of Nikolskoye, and then it was taken to the Iman River. At the end of August 1896, the statue was transported along the Ussuri River to Khabarovsk on the motor boat “Kazak Ussuriysky” and placed in front of the museum. The stone coffin discovered in the large burial mound was first kept by the mill manager and later was delivered to the garden of the Museum of the Society for the Study of the Amur Region in Vladivostok.

Note that when Busse invited the Chinese to participate in the excavations, they refused, because, as he explained “the entire foreign world honored the person who was buried near the turtle. When the tomb was unearthed, several of the Chinese made full prostrations and chanted

prayers, reverently bowing to the monument and the discovered tomb. Each ethnic group was convinced that some legendary popular hero was buried here” (Busse, 1894: fol. 45).

Reconstruction of the funerary complex

In the process of rescuing the turtle statue from destruction, Busse discovered the funerary complex of a Prince from the Jurchen family clan of Wanyan. The stone coffin with the cremated remains of the deceased, set on a platform made of clay and densely packed stones, was located in an earthen mound measuring 14 × 13 m and 3 m high. Four flat stones were placed at its corners. The tomb had the following size: a length of 227 cm, width of 112, and height of 150 cm. The bottom of the tomb was a monolith 20 cm thick, with vertical side edges. Its walls were hewn stone slabs 57.5 cm high, fastened to the base with iron pins 2.5 cm in diameter, and attached together with iron brackets in the form of “butterflies” embedded in the stone. In the corners, the slabs were attached to each other using special rectangular cutouts on one of the sides where the slab without a cutout was inserted (see Fig. 4, 3 ). The tomb had a trapezoidal shape in plan view. Based on this, Busse suggested that it was oriented to the southwest with its “head” part. The coffin lid was a monolith in the shape of a truncated pyramid (see Fig. 4, 5 ). The inner walls of the tomb had no traces of fire, which means that the deceased was cremated outside.

The funerary rite, which involved the burial of animals, birds, and fish with the deceased, was performed during construction of the burial mound. A dog was buried

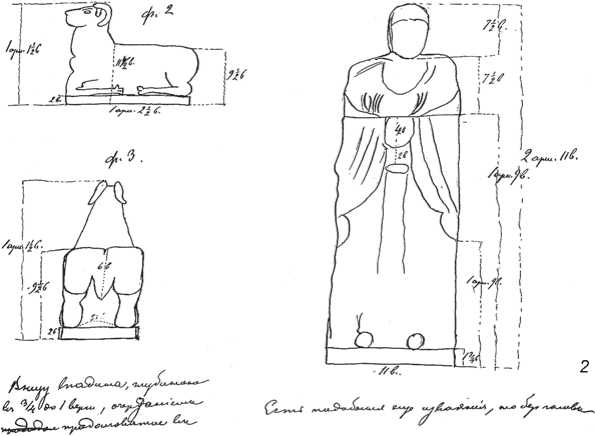

Fig. 5 . Stone statues.

1 – official; 2 – warrior; 3 – lion; 4 – official and rams.

above the coffin lid, and a horse with its head facing south was buried above the dog. The Jurchens always had the custom of burying the deceased of high rank with a horse (Vorobiev, 1983: 129). Bird and fish bones, as well as fragments of clay fishing sinkers, were discovered at the same level as the horse’s skeleton, but slightly to the west. Bone fragments and pig tusks were found slightly higher. No traces of fire were observed on the animal remains.

The stone bixi ( 赑屃 ) turtle, with its head facing south, together with the stele “on the path of the spirit” of Wanyan Zhong (Esikui) was set south of the main burial. A shrine 2.5 × 2.5 m with a tiled roof, with its base supported by six wooden columns, was located to the east of the turtle.

One of the controversial issues associated with the funerary complex of Wanyan Zhong is the presence or absence of stone statues, which were traditionally set in pairs “on the path of the spirit” of the deceased. Their number had to correspond to the rank of the deceased. The History of the Song Dynasty (Juan 124, “Descriptions” 77, ceremonies 27 (funerary rites), “Foreign funerary rites and ceremonies for honoring the memory of the dead; funerals of dignitaries, etc.”) reads: “In front of the graves, there are stone statues of rams and tigers, as well as stone posts, two of each type; when higher than the third rank, two statues of people should be added” (cited after (Lin Yun, 1992: 41)). It was assumed that there used to be at least paired statues of civil officials, warriors, tigers, and rams (Fig. 5), and two stone pillars (Ibid) in front of the grave of Esikui (Wanyan Zhong).

None of the Russian scholars of the funerary complex mentioned that there were stone statues near the statues of the turtles. Most likely, they were no longer there by the time the burial was discovered. According to Busse, when he visited the village of Nikolskoye for the first time in 1866, he saw “two statues of turtles, a grave decorated with three pairs of statues of rams, people, and columns” (1893b). Later, this was erroneously interpreted as Busse having seen a stone turtle with sculptures as part of a single funerary complex, although he was writing about three different burials: two with stone turtles and one with the paired statues of rams, people, and columns. Two years later, one of these turtles (the Ussuriysk turtle) and another burial with stone sculptures of people and sheep were described and sketched by I.A. Lopatin (1869). In 1874, the remains of the statues were photographed by V. Lanin

(Fig. 5, 2 , 4 ). Later, the following was written about them: “From the cemetery church heading west, there is an ancient road about 150 sazhens long; from the point of its intersection with the road heading to the village of Mikhailovskoye, there are two burial mounds about 100 sazhens to the south. The southern burial mound is much smaller than the northern one. On the northern burial mound a pit, which is not very deep, can be seen. According to the testimony of old dwellers, there were originally stone figures on this mound: two rams, two dogs, two people, and a bear. Reported by Lanin in 1897” (Busse, Kropotkin, 1908: 19) (Fig. 6, 2 ). Considering all the available data about these stone sculptures, the conclusion can be made that the statues were not

^ь-й

discovered on the grave of Wanyan Zhong; although, judging by the funerary complex of Wanyan Xiyin (?–1140, Jin dignitary, cousin of Wanyan Aguda), created in the late 12th century in the Upper capital of the Jurchen state of Jin (Huiningfu, currently a part of the Acheng District of Harbin) under the order of Emperor Shizong (1161–1189) (Wu Jin, 2012), they should have been there (Fig. 6, 1 ).

As mentioned earlier, the stele commemorating Esikui (Wanyan Zhong) was erected after 1191, when he was

Fig. 6 . Grave sculptures.

1 – Wanyan Xiyin’s grave ( photo from the Jilin Provincial Museum ); 2 – drawings by I.A. Lopatin (1869).

given his last title of “kaifu yitongsansi jinyuan jun ming yi wang Wanyan Zhong”. Construction of new grave monuments to major statesmen of the Jin Empire (such as Wanyan Aguda, Wingyan Xiyin, etc.) was associated with the policy of exalting the historical past of the Jurchens (Larichev, 1974: 223; Golovachev, 2006). Old burial sites were reconstructed along with building new funerary complexes. The remains of an earlier burial located inside the platform under the statue of the turtle might have been associated with that process. The ashes of the deceased were placed in a stone coffin, and a reburial ceremony was performed.

Conclusions

Relatively few Jurchen burials, such as the Novitskoye (Artemieva, 2018) and Kraskino (Boldin, Ivliev, 1994) burial grounds, have been discovered in Primorye. These burial grounds did not belong to high-ranking Jurchens as opposed to the funerary complex of Wanyan Zhong, which was a unique structure built in honor of a famous representative of the Imperial family clan.

Reconstruction of the architecture in this complex, revealing funerary traditions typical of Jin family cemeteries of the 12th century, was possible only owing to the diaries of F.F. Busse. It has been established that the stone coffin was not lowered into the grave pit. Weapons (arrowheads), food (cereal grains), and roof decorations (a fragment of the sculptural image of a dragon and an end tile) were placed with the cremated remains of the deceased. Funerals of clan chiefs and members of rich, influential families have been known to be especially ceremonial. Their favorite servants, maidservants, and saddled horses were burned, and their remains were placed in the grave as a sacrifice to them. The funerary rite also included burials of pigs, dogs, and birds in the mound. Vessels with beverages were placed in the grave. The entire memorial ceremony was called “cooking porridge for the deceased”. Later, human sacrifices were abandoned. The custom of burying a horse with the deceased existed among the Jurchens even before the creation of their state. A distinctive part of the commemorative ceremony was the ritual of burning food, which was most likely intended to release the spirit of food, since the spirit of the deceased could only use the spiritual essence of a thing (Vorobiev, 1966: 63–64). Judging by the burial of Wanyan Zhong, these customs continued to exist during the state period, but new rituals were added to them. A stone turtle with a stele on its back started being set next to the grave. According to the chronicles, it was called a bixi (赑屃) in China, and was considered one of the nine mythological children of the dragon, symbolizing happiness and longevity. When people wanted to glorify rulers or outstanding figures, and perpetuate their memory, a stele listing the achievements of the deceased was set on the back of the stone turtle so that the magical power of the bixi would contribute to preservation of his great deeds for centuries (Zhang Ruifeng, 2018: 43).

This design of burial places emerged during the Han Dynasty. Six more burial mounds constituting a family cemetery surrounded the burial of Wanyan Zhong. A symbiosis of the borrowed and native Jurchen customs can be seen in the funerary rite, internal layout, and architectural features of the examined funerary complex, confirming the fact that centuries-old Chinese traditions had a significant effect on the development of cultures of various peoples living in the Asia-Pacific region.

It was believed that after the death of Wanyan Digunai (Esikui) in 1148, the Yelan Province began to gradually lose its primary importance and turned into a peripheral region (Larichev, 1964: 634). Currently, there is convincing evidence that the territory where Wanyan Digunai brought the Yelan Wanyan tribe became the district center of the Jin Empire, and later, the city of Kaiyuan—the capital of the Jurchen state of Eastern Xia—was founded there.