Time perception and time management during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

Автор: Elena A. Makarova, Elena L. Makarova, Iakoov S. Korovin

Журнал: International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education @ijcrsee

Рубрика: Original research

Статья в выпуске: 1 vol.10, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Our perception of time changes with age, but it also depends on our emotional state and physical conditions. It is not necessarily mental disorders that distort human's time perception, but threatening or dangerous situations, induced fear or sadness trigger psychological defensive mechanism that speeds up or slows down the rate of the internal clock. Fear distorted time is caused by higher (slower) pulse rate, increased (decreased) blood pressure and muscular contraction. The given research is aimed at improving our understanding of the mechanism that controls this sense, opening the way for new forms of time management. Our perception of time is dependent on our emotional state, temporal distortion caused by emotion is not the result of a malfunction in the internal biological clock, but, on the contrary, an illustration of its remarkable ability to adapt to events around us. Development of time sensitivity is very important for timing, time perception, time-management and procrastination problem solution.

Time perception, defensive mechanism, rhythm of brain activity, internal clock, time management

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170198653

IDR: 170198653 | УДК: 159.942.5:[616.98:578.834(100)"2020" | DOI: 10.23947/2334-8496-2022-10-1-57-69

Текст научной статьи Time perception and time management during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

The relevance of the topic under study is due to the fact that until now the processes and mechanisms of time reflection remain insufficiently studied, phenomenology is very diverse and extremely opposite, just as contradictory used concepts are usually not carried from the reflection area wanderings. Why do people constantly lose sense of time? Everyone has to make unusual decisions about organizing their lives in a pandemic isolation. Therefore, we conducted research in order to study people’s experience of the current situation of uncertainty, their decision-making, time management and self-regulation during a lockdown; find out how the individual psychological characteristics of the personality affect time perception and management in these conditions. The goal of the study is to identify the degree of discomfort that a person experiences when in an ambiguous situation, to determine how different the daily routine is and how a person arranges work\study activity while working\studying online. Determination of gender, age, occupation and social status will make it possible to draw a conclusion about the awareness of the individual about time perception, ability to flexibly adapt to changing circumstances and effectively manage their routine. It is necessary to take into account the emotional component: the ability of people to analyze their behavior, to understand and manage their daily activities in a stressful situation of COVID-19 restrictions.

It seems that online mode of work\study is here to stay. COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed our lives: communication, working environment, self-isolation, quality of life itself, etc. ( Rettie and Daniels, 2020 ). The study examined the impact of rapidly changing environment, remote working and loneliness on people who were grounded for a long period of time, on their individual perception of time. Some recommendations are made for time management and daily routine planning as a result of the study. The survey was conducted from March to August 2021, 85 people took part in the survey, their age,

-

*Corresponding author: makarova.h@gmail.com

© 2022 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

gender, marital status, education, social status were taken into consideration. People face the problem of time every day, every minute. Time is the regulator of all human activities. No activity takes place without the perception of time. Therefore, it is important to know what “time” is, how it is perceived by a person, what its perception depends on and whether this perception changes in extreme or dangerous situations when the whole world is restricted by a PC use. “There is no single, uniform time, but rather multiple times which we experience. Our temporal distortions are a direct translation of the way in which our brain and body adapt to these multiple times, the times of life” ( Droit-Volet and Zélanti, 2013 ).

This can help a person organize activities, use time rationally or irrationally, meet the deadline or procrastinate. Time is a concept, and as any concept is taught to us. The feeling of time depends on future and past ( Stockwell et al., 2021 ). Time exists objectively, continuously one minute replaces another and one day follows another, months, years, centuries pass. But, despite the fact that the course of time throughout the world obeys the same laws, for each individual person the same interval of objectively past time may seem shorter or longer than it actually is. There is a joke that you cannot compare 5 minutes in a queue with 5 minutes on a red-hot stove. For different people, the same period of time can have completely different meanings. For one person the week “stretches” into a month, for another the week “flies” like a couple of days or even hours ( Surani and Hamidah, 2020 ). The purpose of this work is to study the features of human perception of time during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown or self-isolation. The research subject is a change in perception of time while working or studying online from the comfort of one’s own home.

Research by neuroscientist Antonio Damasio shows that decision-making is inextricably linked with emotion, so it is not surprising that anxiety and depression are often characterized as states of being stuck in time and unable to make decisions during an uncertain situation ( Damasio and Carvalho, 2013 ). The problem of psychological time in contrast to physical time was first posed by Henri Bergson “If I look at a road drawn on the map, nothing prevents me from turning back and looking if it forks in places. But time is not a line on which we go back”. He differentiated time from duration, i.e., psychological time: “There is the time that is measured, the time of chronometers and science, a cold parameter like a dead fish. And there is the time that is not measured, which is subjective and incomparable, which is elastic and malleable, the time of the moment, the lived time that is called duration” ( Bergson, 2014 ). The following features are characteristic of psychological time: it continuously changes the world, i.e. leaves a mark on things, is a symbol of change, and has an internal genetic relationship of moments. It should be noted that in this research we focus on psychological time. Psychological time is distinguished in different scales. First, there is a situational scale consisting of the direct perception and experience of short time intervals. Second, there is biographical scale based on the laws that manifest themselves when changes of direct forms of experiencing time in various life situations emerge. A certain system of generalized temporal representations is formed in a person’s consciousness (the concept of life time in the scale of life). Historical - when events that occur before the birth of an individual, and those that occur after his death, are involved in the sphere of temporal relations and act as a condition for the formation of a personal concept and direct experiences of time (for example, genealogical succession). All these scales are interconnected ( Martsinkovskaya and Balashova, 2017 ).

Materials and Methods

Our study is based not on a single method, but on a system of different methods. We used several questionnaires to get information necessary for generalization and conclusion. The first questionnaire used was aimed at problems that people had during COVID-19 pandemic ( Martsinkovskaya and Tkachenko, 2021 ). The second one was designed to evaluate different people’s time perception. one’s own home. Time is a form of the flow of all mechanical, organic and mental processes, a condition for the possibility of movement, change and development, every process whether it is spatial movement, qualitative change, emergence or death, occurs in time.

A person’s perception of time is provided with the help of a biological clock, including time-tested cyclical metabolic processes in the body. Comparing the course of real time with these processes, a person has the opportunity to evaluate it in such parameters as its duration, speed, acceleration or deceleration. The role of a biological clock can be claimed by many processes, for example, rhythmic contractions of the heart muscle, the rhythm of breathing, the rhythm of movement of the arms and legs of a person when walking, daily metabolic processes in the body, the rhythm of the electrical activity of the brain and probably some others, so far not sufficiently studied, but subordinate to a certain rhythm or cyclicality, organic processes (Meyer, McDowell and Lansing, 2020). The perception of time is conditioned not only by the course of the “biological clock”, but also by the content and nature of the activity, which the time interval perceived by a person is filled with. The more saturated with affairs and divided into small intervals a given period of time is, the more individual it seems to a person. The past time in our memories seems to us the longer, the more it was occupied by events significant for us, and on the contrary, it seems shorter if during this time no events significant have happened. The waiting time for the desired event, especially if we “rush” its onset, usually lengthens in our perception (the passage of time seems to slow down). If the corresponding event is undesirable for us and we mentally strive to ensure that it would not occur as long as possible, then on the contrary its expectation in our consciousness is reduced (the course of time in its subjective perception on the contrary accelerates) (Galbraith et al., 2021). The time filled with events with a positive emotional connotation decreases in its experience by a person, and the time filled by the events with a negative emotional connotation, respectively, increases in duration. Long-term research by D. G. Elkin in 1962 showed that there was a direct connection between the perception of time and activity: the more accurate the perception of time, the more successful the activity; the more exciting the activity, the faster time flows (Elkin, 1962).

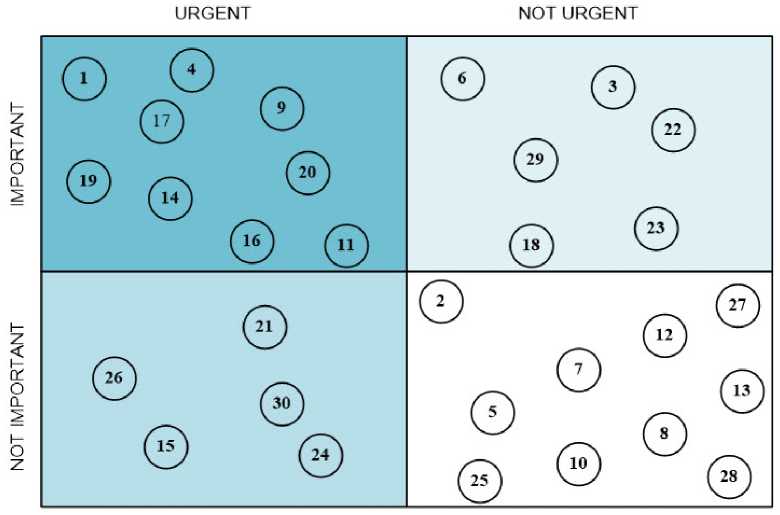

The first part of the questionnaire evaluated quantitative changes in time perception that people noticed during COVID-19 lockdown. The second part of the questionnaire contained open-ended questions that are accountable for the variety of opinions given by people of different age and occupation. In the third part of the study time–management matrix or the Eisenhower Matrix also known as Urgent Important Matrix or the Eisenhower Decision Matrix was suggested as a frequently used model for time management. It should help improve decision making process between priority and minor problems managing time to maintain work-life balance and not get burn out, as many respondents in their answers mentioned lack of time in the situation when some extra time should be found (as people didn’t have to commute or get ready to leave for work or study).

Using simple tools like the time-management matrix helps to keep things organized and reduce emotional stress. Tasks are categorized into specific quadrants, which in turn determine when and for how long you can complete a task:

-

• Quadrant I - “Do it now” (urgent and important). This includes priority tasks that require immediate attention. They have tight deadlines and must be followed above all else and personally.

-

• Quadrant II - “Decide when you will do it” (important but not urgent). The elements it includes are important but do not require immediate intervention or response. At the same time, tasks have a certain deadline and are also performed personally.

-

• Quadrant III - “Delegate as much as possible” (urgent but not important). This quadrant includes phone calls, emails, and scheduling meetings and events. These types of tasks usually do not require personal attention because they do not imply a measurable result.

-

• Quadrant IV - “Do it later” (unimportant, non-urgent). Actions that fall into quadrant IV can always be postponed without fear of any consequences. These tasks take time and interfere with the more important tasks that you put in the first two quadrants.

Using this matrix should definitely help manage time efficiently and effectively in situations of uncertainty and danger when people get stuck in lockdown, but still trying to do their best in work or study.

Results

During the research, a sociological survey was conducted according to the topic “Time Perception and Time Management during COVID-19 Pandemic”. In accordance with the goal and objectives set, a research procedure consisting of three parts was developed. Based on the results of the first part, a quantitative survey of respondents was conducted, which is devoted to attitudes towards COVID-19 in general, the study involved 85 respondents (12 males and 73 females) aged 19 to 65 years, all the respondents were from the education system: full-time bachelor students, part-time master students combining study and work, teachers and professors of the University. Gender factor was not considered, but age was. Teachers and professors of the University not only answered the questions of the survey, but also gave their expert opinion on the issue. The question “What is your marital status?” was answered like this: 59 people (69%) are single / unmarried, 15 people (18%) are married, 4 people (5%) are divorced, 7 people (8%) are in a relationship. The question “What is your occupation?” was answered by the interviewed respondents like this: 45 (53%) students, 30 full-time students (35%), 10 parttime students (12%). The respondents were asked the question “Do you work / study on-line?” 36 people (42%) answered that they study and work on-line; 21 people (25%) are partly on-line, 11 people (13%) remain in the full-time training / work system, 17 people (20%) answered that they had worked online before the pandemic. The answer to the question “Have you restricted physical contacts with other people during COVID-19 pandemic period?” was answered like this: only 10 (12%) people completely stopped contacting other people, the majority of 54 people (64%) answered that they stopped partly, 21 (24%) people did not avoid physical contacts. The respondents were asked the question: Did you have more / less spare time during lockdown? Most of the respondents, 48 people (56%) answered that they had more spare time; 15 people (18%) answered that they had less spare time; 12 people (14%) did not notice any changes, 11 people (12%) didn’t notice any difference before or during COVID-19. The respondents were asked the question “Do you consider the Internet an effective means of communication in the situation of COVID-19?” The majority of 41 people (48%) strongly agreed, 36 people (42%) partially agreed; only 9 people (10%) disagreed. The next question was “Do you follow news about COVID-19 on a regular basis?’ Only 11 people (13%) answered affirmatively, the majority of 45 people’s (53%) answer was “from time to time”, 18 (21%) people did not follow the news about COVID-19 at all. The respondents were asked the question ”Do you feel comfortable being made work / study on-line?” The majority of 37 people (44%) felt comfortable all the time, 30 people (35%) were partially satisfied with working and studying online and only 18 (21%) people did not feel comfortable working and studying distantly. Thus, the first part of the study showed that people who took part in the survey provided demographic variety, their answers were completely different, the majority of respondents enjoyed spare time provided by online work \ study, no need to commute saved time, they enjoyed working \ studying from the comfort of their own home, but they didn’t completely restrict physical contacts with the outside world.

The second part of the study includes mostly open-ended questions and is devoted to people’s individual perception of time during a pandemic. As the study shows, 47 respondents (55%) believed that their daily routine didn’t change during self-isolation period, but 38 respondents (45%) noted that their life had changed dramatically.

About daily routine changes the answers to the open-ended question 4 were like these:

“I have more free time because,” … I don’t spend time commuting and getting ready, everything is at hand, I can conjoin work\study with other activities at home, I was at home for 2 weeks, I didn’t go to work, didn’t waste time commuting (9 people), no need to spend time on a trip to and from work, (in the morning I could sleep longer, since there was no need to pack staff, get ready and spend time travelling), did less work (2 people), I didn’t have to spend a lot of time in traffic jams moving around the city (4 people) , spent time at home (3 people), instead of walking to work, no need to stay late at work (no overtime work), no need to waste time in traffic jams, I finished my master’s degree thesis, during the first pandemic lockdown, I didn’t have more free time; I worked from home (tutoring).

To the open-ended question 5 “I didn’t have enough time for obligatory activities because….” There was a lot of homework (3 people), a lot of offline / online work (7 people), there were chores \housework (2 people), commuting took a lot of time (3 people), the work schedule was less structured (3 people), a lot of work was accumulating that can only be done in the workplace, the whole real life had turned into a virtual one, there was not enough technical equipment for online work of all family members, household chores were distracting, a lot of new activities (2 people), I spent time on procrastination and anxieties, I got tired faster and often took a nap at lunchtime, it seemed that there was too much of it to rush, but I was lazy (2 people), I often got distracted by the phone calls, I don’t know, I wasted time on unnecessary things, new hobbies appeared, I had enough time for everything (9 people).

-

6. The following responses were given to the open-ended question “During self-isolation period I did ....... more, I did .... less” : I stayed at home more (5 people), worked less (2 people), relaxed,

-

7. The following answers were given to the open-ended question “I like / don’t like to function in online mode because…”:

-

2. “During lockdown period the following activities were added to my everyday routine …”.

studied, spent time with my family (3 people), did household chores, watched movies, took care of my health, spent time meditating, went jogging less, self-developed (2 people), focused on courses, ate, slept more (4 people), went in for sports, developed new hobbies, read (2 people), worked at the computer (3 people), spent time surfing the Internet, I got tired more, spent time at home (3 people), did work less, procrastinated more, did exercises, walked more, worked, slept, ate more (2 people), I wanted to do something extra, listened to music, watched cartoons, was distracted from work\study, spent time with children more, was into self-development more, I was stressed less, relaxed (8 people), talked with friends / relatives (7 people), moved around the city, spent time driving, complained about the lack of time more, got nervous, played sports (2 people), was nervous (2 people), I slept at work, walked in the parks or shopping centers, communicated with people, spent money shopping online, socialized at work.

I like working online because ….. it’s better to work from home, it’s comfortable, both online and offline are good for me, I can work / study from anywhere, I don’t need to go anywhere, it saves time, I’m an introvert (I don’t need to communicate with people), it’s easier to schedule things when you work from home, I interact with people less, I like a regular lifestyle, I experience less stress, have more time for selfdevelopment, have more free time, I don’t have to worry about my appearance, I don’t need to go to the office, my home is a comfortable environment both for work and study, I have more time, it is convenient, it is easier to find time for household chores, even when I feel unwell, I can attend classes, do not commute, I can superpose several activities (work\ study and some housework), I can work at your own pace.

I don’t like it because …. academic performance has become much lower and there is not enough live communication and socialization, no time is saved, I have to do household chores, more time with family and friends means less time spent on work\ study, my home is not well-equipped for online study, I have poor contact with teachers, I communicate with people less, I go crazy being alone in my home, information is better absorbed in discussion and interaction, I get tired of a computer, I like face-to-face studies, everyday routine distracts, I need eye contact with the teacher and classmates, there are communication failures, I cannot meet deadlines working\studying from home, I do not participate in the activities of the university, I do not feel alive.

The following answers were given to the open-ended questions of the survey:

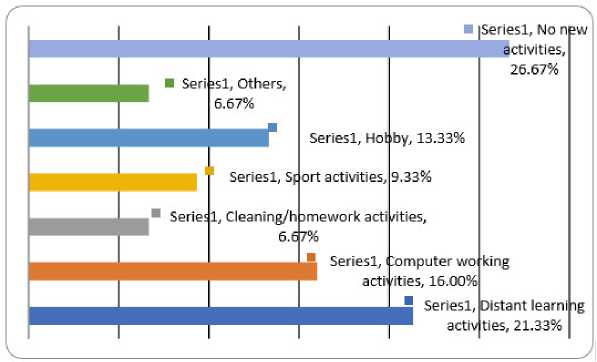

distant learning\working activities 21.33%, computer working activities 16.00%, cleaning / homework activities 6.67%, sport activities 9.33%, hobbies 13.33%, others 6.67%, no new activities 26.67%. Also, other activities were mentioned: online courses, household chores and babysitting, cooking, working out at home, cleaning, Spanish classes, organizing the learning process for children, watching TV shows / cartoons, taking long walks with the dog.

Figure 1. New activities added to regular schedule during COVID-19 lockdown

”

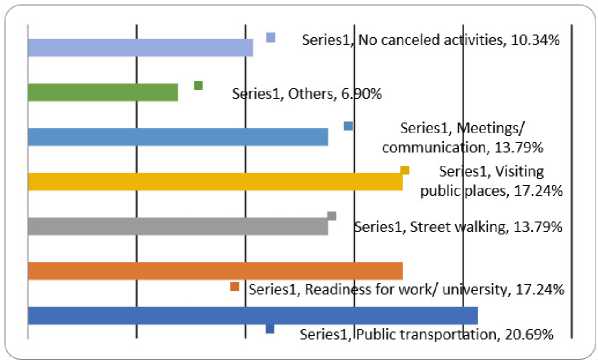

3. “The following activities were canceled during lockdown period

commuting 20,69% , getting ready for work/ university 17,24%, street walking 13,79%, visiting public places 17,24%, meetings/ communication 13,79%, others 6,90%, no canceled activities 10,34%.

Figure 2. Activities deleted from the regular schedule during COVID-19 lockdown

Also, other activities were mentioned: going to college, going to school, meeting friends, chatting with people, eating fast food, going to the grocery store, applying makeup, attending events, dressing up, hiking, going to the gym, meeting elderly relatives, face-to-face interaction with students and colleagues.

In the third part of our study, recipients were asked ‘to fill out this questionnaire by highlighting the statements that characterize your everyday routing during COVID-19 pandemic arranging them according to importance and urgency’. This made it possible to form a time-management matrix in the era of a pandemic when working in distant mode. This matrix is an example of the average indicators of the entire surveyed group, however, it can be filled out individually in order to plan your activities, manage time and set priorities (Fig.3).

Figure 3. Time-management matrix example

-

1. Every day I use an on-line platform (Zoom, Teams, Skype, etc.) and get ready to on-line meetings.

-

2. Every day I check if the clock is visible in the room where I have my on-line meetings.

-

3. Every day I arrange (take part in) meetings that have a certain goal, have a time limit and reach this goal.

-

4. I check my E-mail as soon as it gets into my mail-box, usually the same day, and read messages at once.

-

5. I scan all the articles and on-line news, especially about COVID-19.

-

6. I block all spam letters and advertising sites, delete my name from the delivery lists of on-line magazines that I don’t read.

-

7. I can find solution to several problems without being distracted from Zoom, Teams, Skype meetings or on-line game.

-

8. I decide how many meetings a day in Zoom Teams, Skype to plan.

-

9. I plan certain time for communication with friends and relatives.

-

10. I don’t answer letters, SMS and phone calls when I am busy working (homework, getting ready to lectures, attending classes via Zoom, etc.).

-

11. I always answer the call but say that I will call back later.

-

12. I limit time on the phone and chatting on-line.

-

13. I never answer the phone, but check the messages left later or read SMS.

-

14. I decide how many phone calls a day to make, whom to call and how long to communicate.

-

15. I scan SMS messages as soon as I get them, no matter if there is a meeting in Zoom.

-

16. Later I read messages carefully and answer those to be answered.

-

17. I save all the letters in my mail-box, don’t delete any letters.

-

18. I delete all the documents from my PC as soon as I don’t need them anymore, I also delete SMS messages from my phone as soon as I read them.

-

19. I prefer to copy somebody else’s solution of problems rather than do them myself, saving time.

-

20. I carefully check the homework I give to my students and grade them (I do all the assignments

-

21. I ask students to limit their written papers to one page (I briefly do my written homework, never copying unnecessary material).

-

22, I decide whom to give information, which assignments to offer (I decide which assignments to complete and in which subject).

-

23. I reach the balance between thinking time and action time.

-

24. Every day I make a list of things to do, checking in the evening which ones are completed.

-

25. I spend limited time a day in front of my computer, not more than necessary.

-

26. I try to keep in touch with my friends and acquaintances personally, not only via phone or chat.

-

27. I communicate only with people who inspire positive emotions and avoid those who are negative.

-

28. I am sure I am aware about all the latest information technologies and newest gadgets.

-

29. I save all E-mail letters in order to reread them later.

-

30. I regularly check files in my computer and delete everything that I don’t need.

that a teacher gives).

Our study has shown that although people cancelled some of their time-consuming activities during lockdown period (commuting, meeting people, chatting with them etc.), they still lacked spare time because of the ineffective time management and procrastination. Being on their own during the lock-down period, people relaxed a lot, slept longer, spent time surfing the net or watching TV, thus contributing to waste of time leading to missing deadlines and lowering productivity. The above mentioned matrix is to help and arrange urgent and important activities in one part of the matrix, non urgent and unimportant activities in another part of the matrix thus contributing to the effective and efficient time-management. The matrix also helps and differentiates objective time (it does not depend on a person) and subjective time (feeling the flow of the own time). The respondents had the opportunity to try and arrange their daily activities according to the matrix provided.

Discussions

The simplest form of human perception of time is the perception of one’s own “biological clock”, which contains characteristics such as duration and sequence. Practically all living beings on the planet have a rhythmically changing state of functional systems. This formed the basis for the biological hypothesis of the perception of time by H. Hoagland ( Hoagland, 1933 ). In humans, more than 100 different physiological parameters change with a period of 24 hours. These daily fluctuations can persist both in the absence of any external and internal factors (for example, sleep deprivation). A person is not able to thoroughly monitor the parameters of own body and does not need this, but people are able to arrange their lives in time. For example, the existence of “owls” and “larks” depends on coordination of optimal physiological and mental wakefulness with the cycle of the day, upon reaching which the human body is ready for productive functioning.

Famous Russian physiologist I.M. Sechenov’s concept of the physiological foundations of experiencing time is of exceptional value: “Time is a very general concept, because very little of the real is felt in it. But it is precisely the latter circumstance that indicates that it is based on a part of a concrete idea. Indeed, only sound and muscle sensations give a person an idea of time, moreover, not with all of its content, but only with one side: the viscosity of the sound and the viscosity of the muscular feeling. When an object moves in front of my eyes, following it I move gradually either my head or my eyes, or both together; in any case, the visual sensation is associated with a stretching sensation of contracting muscles, and I say: “The movement stretches like a sound.” People’s daytime life is spent in the fact that they either move, receive a stretching sensation or see the movement of other objects – and again they hear stretching sounds (and olfactory and gustatory sensations also have a viscous character). Hence, it turns out that the day stretches like a sound; 365 days stretch like a sound, and so on. Separate the nature of viscosity from representations of the movement of a day and a year and you get the concept of time” ( Sechenov, 2019 ). The deep analysis reveals an internal dialectical connection between the experiences of time and the spatial-motor functions and the process of generalization and reflection in the consciousness of objective time during which the body moves in objective space.

Another Russian physiologist, academician Pavlov I. P. experimentally showed the possibility of a conditioned reflex development in dogs. Pavlov believed that for the central nervous system time is as real a stimulus as any of the well-known ones. In the body itself, according to Pavlov, there are many cyclic phenomena. The function of time estimation is performed by the central nervous system as a whole. How can we physiologically understand time? - With the help of various cyclical phenomena, the setting and rising of the sun, the movement of the clock’s hands, etc. But people also have a lot of these cyclical phenomena in their body. And since each state of every organ can be reflected in the cerebral hemispheres, there is a reason to distinguish one moment of time from another” (Pavlov, 2012).

The next, more complex situation in which a person perceives the duration of time intervals, which was studied by the Russian psychologist D. G. Elkin (he turned to the problem of time perception back in the 1940s) is activity ( Elkin, 1962 ). The nervous processes accompanying purposeful conscious activity can be studied, but doubts always arise about a person’s ability to reliably interpret the knowledge gained. Depending on the prevailing conditions, the type of activity, the emotional-volitional component, the physical state of the body at the moment, the type of person’s temperament, priorities, goals, motives, etc., an individual assessment of time may be different. When assessing the duration of an activity that was pleasant in nature, people tend to exaggerate the time interval, and if the activity was unpleasant, to underestimate it. Karl von Vierordt, a German physiologist, formulated a law: “When people estimate the duration of short periods of time, they usually overestimate their duration, and when long periods are subject to estimation, they underestimate it” ( von Vierordt, 1868 ), thus contributing to psychology of time perception.

Individual differences in people affect the subjective assessment of the length of time. Thus, in the experiments of H. Ehrenwald ( Ehrenwald, 1923 ), some subjects showed a persistent tendency to underestimate, while others - to overestimate time. In this regard, H. Ehrenwald suggested the need to distinguish between two individually unique types of time estimation: bradychronic and tachychronic. The terms are analogies to “bradycardia - a condition typically defined wherein an individual has a resting heart rate of under 60 beats per minute” and “tachycardia - a heart rate that exceeds the normal resting rate”. The first is characterized by an overestimation of the speed of time, the second - by its underestimation, and the individual differences between people, correlated with these two types of time estimation, turned out to be stable.

“Perception of time is a figurative reflection of such characteristics of phenomena and processes of external reality as duration, rate of flow and sequence. Various analyzers are involved in the construction of the temporal aspects of the picture of the world ( Hookway, 2005 ), of which the kinesthetic and auditory sensations play the most important role in the precise distinction of time intervals” ( Güss, 2013 ). Individual perception of time periods duration significantly depends on the intensity of the activity performed at this time, and on the emotional states generated in the course of activity ( James, 2021 ; Luria, 2018 ; Rubinshtein, 2016 ; Vainshtein, 2005 ).

Human perception of time has been studied much less than the perception of space. This is due to the fact that the spatial characteristics are very visual, real and can be reduced to an experiment. In the modern scientific picture of the world, time and space are connected with each other and with material bodies, therefore, temporary changes can be judged by the change in the physical state of the material world. People are able to judge about temporal characteristics, as about real ones, only by certain criteria, with the “passage of time”. It turns out to be a kind of paradox. To notice that a day has passed, it is enough for us to see the change of the sun and the moon; however, for these changes to actually occur, time must pass ( Rubinshtein, 2016 ).

In order to combine time and space the concept of “chronotope” can be used. This concept is defined as a regular relationship of space-temporal coordinates. In the past, present and future, from separate and unsynchronized images, in the process of social construction, certain centers of grouping objects, time and values - chronotopes, interconnected in space and time by semantic meanings are formed. Chronotopes are “no longer abstract points, but living and indelible events from being”, connected not only by a random sequence, but also by life itself, by the will of living beings, regardless of whether these events are real or not ( Zhuravlev and Kupreychenko, 2011 ). The concept of “chronotope” combines both time and space (the Greek word ‘chronos’ meaning time and ‘topos’ meaning place). Traditionally the chronotope is understood as the time-space continuum in which a person exists. The concept was introduced by A. A. Ukhtomsky ( Ukhtomskiy, 2022 ): “From the point of view of the chronotope, there are no longer abstract points, but dependencies which express the laws of existence are no longer abstract curves in space, but ‘world lines’ that connect long-past events with the given moment and via them - with the events of the future” ( Ukhtomskiy, 1996 ). This term became widely known due to its active use in the field of aesthetics by Michael Bakhtin: “The essential interconnection of temporal and spatial relations, artistically mastered in literature is called a chronotope (meaning ‘time-space’)” ( Bakhtin, 2011 ). Since the beginning of the 1990s the idea of a chronotope as applied to psychology has been actively developed by V. P. Zinchenko: “The peculiarity of a chronotope is that it combines something that seems incompatible. Namely, spacial-temporal in the physical sense of the word, bodily limitations with the infinity of time and space, that is, with eternity and with infinity. The first concept is ontological, which rewards a person with death in the end; the second is phenomeno-logical coming from culture, history, from the noosphere, that

-

is, from eternity to eternity with all conceivable universal human values and meanings. In any behavioral or activity act performed by a person, we have all three time periods: past, present and future, that is, even a chronotope of living movement can be considered as an elementary unit of eternity… Of course, a chronotope is still a metaphor that successfully describes a space-time continuum in which human development proceeds, understood as a unique process within the Universe” ( Zinchenko, 2012 ). According to most scientists, separately taken space and time are just a “shadow of reality” ( Lawson, 2011 ; Loginova, 2010 ; Perrino, 2022 ), but real events occur undividedly in space and time, in a chronotope.

The mentally ill often complain about a change in the consciousness experiences of movement and space within the body, as well as in external phenomena and a change in the sense of time. This problem, especially the problem of time is one of the underdeveloped chapters in psychology and psychiatry. A number of authors divide the sense of time into “I - time” and “world time”. We consider the concept of time by E. Husserl and M. Merleau-Ponty, which makes it possible to understand the origins of the modern problem of conceptualization of temporality and see possible ways of solving it. Time is recognized by researchers as central in the work of E. Husserl, according to the founder of phenomenology time is the basis of all experience, and experience is the only thing that we have. E. Husserl presented the most consistent views on temporality in his work “The Phenomenology of the Inner Consciousness of Time” ( Husserl, 1991 ), which is a lecture, the main theme of which is related to criticism of psychology of time sense in humans. M. Merleau-Ponty (recognizing this point of view calls “I-time” - “bodily time” and believes that it flows unconsciously in a person) identifies the bodily sense of time with the sense of rhythm. The lower the level of an animal or a person, the more the parallelism of the world rhythm with its own subjective rhythm is noted. Thus, “I - time” or “bodily time” is a primitive sense of time ... According to the author, there is also a Gnostic sense of time - as the ability to place lived segments of time along the timeline. Our “I” has a consistent series in the history of our own experiences. This Gnostic sense of time is subject to changes in both pathology and normality ( Merleau-Ponty, 2020 ). A. Carrel figuratively represents physiological and physical time in the form of two trains rushing in parallel. One of them (physical time) goes at a constant speed; at first the other one goes with the same speed, but then its speed decreases more and more - this is physiological time. If we are at the window of the second train in which we are going, we look at the first, then at first we will not notice the difference in speed, but then the further, the more we lag behind, the faster the other train (physical time) rushing will appear to us ( Carrel, 2018 ). For children, time seems to flow slowly; for old people, time rushes by quickly ( Ehrenwald, 1978 ).

People are able to forget about the duration and sequence of events, which means that such a mental process as memory plays an important role in the perception of time. The perception of the past, present and future ensures the normal functioning of a person in society. Russian psychologist S. L. Rubinshtein believed that all human life, including psychological well-being, depends on the awareness and the possibility of reproducing the timeline, consisting of successive causal relationships, memories, emotionally colored events and prospects for the future (an important role is given to the imagination) ( Rubinstein, 2017 ). To make it easier for a person to navigate the time sequence in the modern world there are many ways to document all kinds of details of everyday life, which, on the one hand, opens up prospects for a deeper understanding and study of facts, but on the other hand, causes contradictions in one’s own memories. In psychology, the perception of time is associated with intelligence.

-

Y. V. Bushov and M. V. Svetlik focus on the fact that the faster the neural connections are activated, the faster the operation to find a solution to the situation is performed. The faster the problem is solved, the more real time is left for the solution of the following, i.e. the volume of possibly solvable problems increases. Therefore the less time it takes to search for “answers”, the higher the intellectual level ( Bushov, Svetik and Krutenkova, 2010 ). In his work B. I. Tsukanov describes the quality of the “internal clock” and the problem of intelligence, it was found that the accuracy of time perception in persons with high intelligence is also high ( Tsukanov, 2000 ). This is due to the fact that every single moment in time, the brain processes an incredible amount of information received both from the external environment and from the body. When the process of its merging into a single whole takes place and a more unique moment in physical space and time is created, the brain will be able to create and comprehend a complete picture of the moment. As stated in the definition of the concept of “perception of time”, the most important role in the exact distinction of time intervals is played by kinesthetic and auditory sensations (according to Sechenov, 2019 ).

Ancient philosophers saw time as a measure of movement. Although some Greek philosophers considered time as illusion, others believed that the flow of time was the very essence of reality (Grünbaum, 1974). Albert Einstein expressed his doubt about the distinction between past, present, and future in a letter to his longtime friend Michelle Besso: “People like us, who believe in physics, know that the distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion. … time itself is not what is in question here but rather the passage or flow of time” (Medicus, 1994).

From the early childhood, a person is taught to count and has to count for the rest of the life. Some people are able to very accurately measure the time: professional musicians, the military, athletes, dancers, etc. (according to some research, in the course of special long-term training, a person learned to increase the accuracy of the perception of time intervals) ( Grondin, 2010 ). All these studies also involve the individual recitation of small time intervals that are necessary for the coordination of movements and actions. The connection between articulation, auditory sensations, the action itself and the comparison of response signals becomes obvious.

Like all mental processes, the perception of time is investigated using the substrate-carrier of the psyche - the brain. The subjects of the most research in this area were the people who suffered or had had traumatic experience. The “activation complex” of the time perception process was disturbed in the subjects. Therefore, the information received cannot be absolutely identical for people in the situation of COVID-19. The difficulty lies in the fact that the perception of time is based on other mental processes and cannot be investigated in isolation. In research by the Russian scientists the role of the left and right hemispheres of the brain is also ambiguously interpreted. L. Y. Balonov, V. L. Deglin, D. A. Kaufman, N. N. Nikolaenko in their work “On the functional specialization of the cerebral hemispheres of the human brain in relation to the perception of time” ( Balonov et al., 1980 ) indicate that time flows differently in different hemispheres: the right hemisphere functions in the present and the past, the left - in the present and the future; people’s own physiological time goes faster in the right hemisphere. These data imply that duration is estimated differently by both hemispheres. There is another side to the issue: the perception of time becomes possible only with the joint simultaneous processing of information and the delays mentioned above would lead to a malfunction of the entire system.

It is also unclear whether the perception of time is innate or acquired. It is impossible to appreciate the inalienable meaning that people put into time. According to Y. Bushov, life is the time intervals from one heartbeat to another. No matter what situations a person finds himself in, one is still forced to live with an internal “ticking clock”, which cannot be stopped without ending life itself (Bushov et al., 2019). Physiology does not want to give in to the psychological aspects of this phenomenon. In the entire animal kingdom, only human is able to realize the importance and study the beating of the own heart, however, like no one else, humans seek to exalt themselves above the rest of the world, in the role of the bearers of reason; no matter how much knowledge people get, what they want to achieve, their timer keeps ticking and ticking, time is running out; the mind cannot separate from the body and live on, just as a man cannot take over nature. People were destined to “invent” time in a purely human interpretation (meaning the perception of time from the point of view of the past, present and future), which would bring together every person who has ever lived, would act as an eternal force beyond the control of human, and absolutely everyone feels own heartbeat. From this we can conclude that all the basics of time perception were given to people from birth, but the perception of time in the form in which a modern person can operate with it is a complex mental process acquired by own needs. At the age of two, the child cannot answer the temporal question “when?”, but already understands that the answer must contain a temporal category (today, tomorrow, yesterday, etc.). According to the research data of the French psychologist P. Janet, the very first two concepts in the perception of time “now” and “not now” are formed (Carroy and Plas, 2000). Further, in the process of the child’s development, with active teaching by parents, with the normal development of a child’s self-concept, an understanding of one’s own place in a situation and awareness of the place of others in it is formed. Thus, the conceptual base is being filled, and by the age of three, the child is already able to name a decent temporal hierarchy. One of the main temporary concepts is “now”. The ability to assess a given moment in time can deeply characterize a person. The very fact that, when describing the word “now”, in most cases, information contains a spatial character and a description of changes in the physical characteristics of objects, it makes a connection between the description of time and actions, which was already mentioned in the first paragraph. To describe what was then and what is now, the environment must change; in most of these changes, both nature and man play a major role. From this it follows that the activity not only affects the nature of the perception of time in terms of the dependence of the situation and the individual attitude to it, but also serves as the very instrument with which it is possible to give oneself an account of the change in the stages “before” and “after”. A person is able to set goals that are far from the present, capable of performing multiphase actions (unlike animals). This means that time-oriented purposeful activity is itself a mechanism for measuring intervals of different duration. For example, such a concept as “always” cannot absorb the meaning of the eternal and permanent, since the physical world changes every second, but it has a strong emotional character, implying the constant attitude of a particular person to something (someone) outside of time. From all of the above, we can conclude that the potential for a detailed study of the perception of time is great. There is a lot of knowledge on the basis of which experiments can be designed to study this problem. Physical, psychological, neurophysiological, anthropological and historical knowledge can someday be combined into a single methodology that reveals the mysteries of this mental process. A person has a subjective perception of time, developed in the process of life, as well as internal biological time, which characterizes the course of the rhythmic cycles of the body. The topical location of the mechanism responsible for the individual assessment of time has not yet been found, however, its work is associated with the joint inclusion of all mental processes.

Conclusions

In the study we have considered processes associated with the idea of time in the psyche (representation), as well as the construction (creation) of time in the periods of lockdown during COVID-19 pandemic. However, we cannot be limited to the fact that we somehow perceive time, reflect it in our psyche (represent), and predict the development of the situation. In addition, our psyche is capable of more – constructing and managing time. This is already an active, directed process; however, it may not always be efficient. People are actively looking over options, choosing the most suitable one (according to some criteria - these are not necessarily the “most profitable” criteria), and even, perhaps, specially plan their further actions. Depending on the degree of efforts made, they change the world around, thereby changing space, time and meanings - not only their own, but also the entire environment. This can be called effective and efficient time management. If the past can be represented (remembered), then the future can be not only imagined - represented, but also constructed. Objective time differs greatly from subjective time (the way the person feels it). Subjective (psychological) time is a reflection in the human psyche of the system of temporary relations between the events of his life path. Psychological time includes: assessments of simultaneity, sequence, duration, speed of various life events, their belonging to the present, remoteness in the past and the future, experiences of compression and elongation, discontinuity and continuity, limited and infinite time, awareness of age, age stages (childhood, youth, maturity, old age), ideas about the probable life expectancy, about death and immortality, about the historical connection of one’s own life with the life of previous and subsequent generations of the family, society, humanity as a whole ( Davidson and Sternberg, 2003 ; Grondin, S. 2019 ; Zogby, 2017 ).

Using a matrix to evaluate urgency and importance of activities helps building a mental model of temporal relationships and determining the place of a person in it based on the perception of time. Naturally, it is not a purely individual human psyche that is involved in this, but the role of social mediation (social time and its relationship with subjective time), as well as sign and behavioral expression (shows how a person adjusts subjective time in the environment) is also very important. This is a transition from biologically perceived time (perceptual, immediate) to socially mediated (conceptual).

Acknowledgements

The reported study was a part of the RFBR project number 20-04-60485.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Список литературы Time perception and time management during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown

- Bakhtin, M. M. (2011). Art and Answerability: Early Philosophical Essays (University of Texas Press Slavic Series Book 9) 1st Edition, Kindle Edition 467.

- Balonov, L. Y., Deglin, V. L., Kaufman, D. A., & Nikolaenko, N. N. (1980). O funktsional’noy spetsializatsii bol’shikh polushariy mozga cheloveka v otnoshenii vospriyatiya vremeni [On the functional specialization of the cerebral hemispheres of the human brain in relation to the perception of time]. Faktor vremeni v funktsional’noy organizatsii deyatel’nosti zhivykh system. [Time factor in the functional organization of the activity of living systems]. L ., Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 119–124.

- Bergson, H. (2014). Time and free will: An essay on the immediate data of consciousness. Routledge. https://doi. org/10.4324/9781315830254

- Bushov, Y. V., Svetlik, M. V., & Krutenkova, E. P. (2010). γ-Activity of the cerebral cortex: Relationship between intelligence and the accuracy of time perception. Human physiology, 36(4), 382-387. https://doi.org/.1134/S036211971004002X

- Bushov, Y. V., Svetlik, M. V., Esipenko, E. A., Kartashov, S. I., Orlov, V. A., & Ushakov, V. L. (2019). The activity of human mirror neurons during observation and time perception. Современные технологии в медицине, 11(1), 69–75. https://doi. org/10.17691/stm2019.11.1.08

- Carrel, A. (2018). Man, The Unknown. Kindle Edition, 287.

- Carroy, J., & Plas, R. (2000). How Pierre Janet used pathological psychology to save the philosophical self. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 36(3), 231-240. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6696(200022)36:3<231::AID-JHBS2-3.0.CO;2-I

- Damasio, A., & Carvalho, G. B. (2013). The nature of feelings: evolutionary and neurobiological origins. Nature reviews neuroscience, 14(2), 143-152. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3403

- Davidson, J. E., Sternberg, R. J., & Sternberg, R. J. (Eds.). (2003). The psychology of problem solving. Cambridge university press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511615771

- Droit-Volet, S., & Zélanti, P. S. (2013). Development of time sensitivity and information processing speed. PloS one, 8(8), e71424. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071424

- Ehrenwald, H. (1923). Versuche zur Zeitauffassung des Unbewussten [Attempts at the time perception of the unconscious].«Archiv für die gesamte Psychologie» [«Archive for the whole of psychology»]. Leipzig, Wilhelm Engelmann, 45, 144-157.

- Ehrenwald, J. (1978). The ESP Experience: A Psychiatric Validation. Basic Books Inc. Publishers, NY, 308.

- Elkin, D. G. (1962). Vospriyatiye vremeni [Perception of Time]. - M., APN RSFSR Publishing house, 312.

- Galbraith, N., Boyda, D., McFeeters, D., Hassan, T. (2021). The mental health of doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Bulletin, 45(2), 93 – 97. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2020.44

- Grondin, S. (2010). Timing and time perception: A review of recent behavioral and neuroscience findings and theoretical directions. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 72(3), 561-582. https://doi.org/10.3758/APP.72.3.561

- Grondin, S. (2019). The Perception of Time: Your Questions Answered (1st ed.). Routledge. 184. https://doi. org/.4324/9781003001638

- Grünbaum, A. (1974). Philosophical Problems of Space and Time. Second enlarged edition. Boston: D. Reidel Publishing. 902. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-0 I 0-2622-2

- Güss, C.D. (2013). “Time perception,” in Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural Psychology, ed .K. Keith. New York: Wiley-Blackwell Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118339893.wbeccp542

- Hoagland, H. (1933). The physiological control of judgments of duration: Evidence for a chemical clock. The Journal of General Psychology, 9(2), 267-287. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1933.9920937

- Hookway, C. (2005). William James: Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking. In J. Shand (Ed.), Central Works of Philosophy, Acumen Publishing, 54-70. https://doi.org/10.1017/UPO9781844653614.005

- Husserl, E. (1991). On the Phenomenology of the Consciousness of Internal Time (1983-1917). Translation J. Brough. Springer, 468.

- James, W. (2021). Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Methods of Thinking. Maven Books, 144.

- Lawson, J. (2011). Chronotope, Story, and Historical Geography: Mikhail Bakhtin and the Space-Time of Narratives. Antipode, 43: 384-412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00853.x

- Loginova, I.O. (2010). Education of a Human Being as a Possibility for Life Self-fulfillment: Systemic and Anthropologic Approach. International Journal for Cross-Displinary Subjects in Education, 1(3), 48-56. https://doi.org/10.20533/ ijcdse.2042.6364.2010.0013

- Luria, A.R. (2018). The nature of human conflicts. Franklin Classics Trade Press, 450.

- Martsinkovskaya, T. D., Balashova, E.Y. (2017). Category of chronotope in psychology. Questions of psychology. 6, 56–67.

- Martsinkovskaya, T. D., Tkachenko, D. P. (2021). Questionnaire “Experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic”. New psychological research. 1, 54–68. https://doi.org/10.51217/npsyresearch_2021_01_01_03

- Medicus, H. A. (1994). The Friendship among Three Singular Men: Einstein and His Swiss Friends Besso and Zangger. Isis, 85(3), 456–478. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/235463

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (2020). Phenomenology of Perception (Classic Reprint). Kindle Edition. Forgotten Books. 492.

- Meyer, J., McDowell, C., Lansing, J. (2020). Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviour due to the COVID-19 outbreak and associations with mental health in 3,052 US adults. Cambridge Open Engage. https://doi.org/10.33774/ coe-2020-h0b8g

- Mikhalskiy, A. V. (2014). Psikhologiya konstruirovaniya budushchego [Psychology of designing the future]. Moscow, Moscow State Pedagogical University, 289.

- Pavlov, I. P. (2012). Conditioned Reflexes. Kindle Edition, 450.

- Perrino, S. (2022). Chronotope. In The International Encyclopedia of Linguistic Anthropology, J. Stanlaw (Ed.). https://doi.org/ 10.1002/9781118786093.iela0050

- Rettie, H., Daniels, J. (2020). Coping and tolerance of uncertainty: Predictors and mediators of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist. 76(3), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000710

- Rubinshtein, L. S. (2016). Prichinnoye vremya [Causal time]. M . Corpus, 477.

- Rubinstein, S. L. (2017). Bytiye i soznaniye. O meste psikhicheskogo vo vseobshchey vzaimosvyazi yavleniy material’nogo mira [Being and Consciousness. On the place of the psychic in the universal interconnection of the phenomena of the material world]. Peter, LitRes, 590.

- Schwartz B. L., Krantz J. H. (2018). Sensation and Perception. Second Edition. SAGE Publishing.

- Sechenov, I. M. (2019). Physiologische Studien über die Hemmungsmechanismen für die Reflexthätigkeit des Rückenmarks im Gehirne des Frosches (German Edition). Wentworth Press. 64.

- Stockwell, S., Trott, M., Tully, M., Shin, J., Barnett, Y., Butler, L., ... & Smith, L. (2021). Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviours from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a systematic review. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 7(1), e000960. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000960

- Surani, D., & Hamidah, H. (2020). Students perceptions in online class learning during the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal on Advanced Science, Education, and Religion, 3(3), 83-95. https://doi.org/10.33648/ijoaser.v3i3.78

- Tsukanov, B. I. (1991). Kachestvo «vnutrennikh chasov» i problema intellekta [The quality of the “internal clock” and the problem of intelligence]. Psychological journal. 12(3), 38–44. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1993-33970-001

- Tsukanov, B. I. (2000). Vremya v psikhike cheloveka [ Time in the human psyche]. Monograph. Odessa, Astroprint, 220.

- Ukhtomskiy, A. (1996). Intuitsiya sovesti: Pis’ma. Zapisnyye knizhki. Zametki na polyakh [Intuition of Conscience: Letters. Notebooks. Notes in the margin]. - SPb., Petersburg writer, 525.

- Ukhtomskiy, A. A. (2022). Dominanta [Dominant].-SPb, Peter, 512.

- Vainshtein, L. A. (2005). Psikhologiya vospriyatiya [Psychology of perception]. Minsk, Theseus, 224.

- von Vierordt, K. (1868). Der Zeitsinn nach Versuchen [The experimental study of the time sense]. H. Laupp, 200.

- Zhuravlev, A. L., Kupreychenko, A. B. (2011). Psikhologicheskoye i sotsial’no-psikhologicheskoye prostranstvo lichnosti i gruppy: ponimaniye, vidy i tendentsii issledovaniya [Psychological and socio-psychological space of the individual and the group: understanding, types and trends of research]. Psychological journal. M., 32(4), 45 – 56.

- Zinchenko, V. P. (2012). Formation of Visual Images: Studies of Stabilized Retinal Images. 1972nd Edition, Kindle Edition, 134.

- Zogby J. P. (2017). The power of time perception: control the speed of time to make every second count. Time Life Series, 247.