Tourism as geopolitical strategy: the institutional trajectory of tourism public policies in Ecuador

Автор: Pimentel Thiago Duarte

Журнал: Современные проблемы сервиса и туризма @spst

Рубрика: Региональные проблемы развития туристского сервиса

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.16, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This paper analyzes how tourism has been used as a geopolitical strategy by the Republic of Ecuador throughout the last century, gaining remarkable relevance in the recent period, being considered as an alternative source of development in the context of the restrictive capacities and resources of the National State. In particular, we analyzed the institutional trajectory of tourism public policies in Ecuador, between 19902020, focusing on the role and form of state action in this process. To this end, an empirical study was carried out, based mainly on secondary data collected from the official press of the Republic of Ecuador, in its three branches (executive, legislative and judiciary). From a total of 19,026 documents initially identified, we reviewed and found a total of 223 normative acts specifically dedicated to the tourism issue. This material was analyzed using the institutional model of public policy analysis elaborated by Pimentel (2011; 2014), structured in 3 dimensions and 5 categories, which deals with the normative, regulatory and cognitive dimensions, drawn upon a synthesis of several categories identified by Scott - among others - on institutional theory. The data showed that: a) there is a clear growth in the volume of national normative acts in the period in question, which suggests that tourism has become a State policy, b) the policies are “initiated” and have the executive as the main participating actor, c) however, they are mostly generic acts and poorly linked to operational actions (with plans, projects and measurement instruments) what suggest that extraofficial actions have been taken in order to promote and operate the sector, and d) they are characterized by the absence of resources to make them feasible. We conclude tourism has become a state policy, in terms of the discursive and also institutional level of official actions taken by the national government, as well as the practice we can see in relation to inbound and domestic flows. However, the way the subject is handled lacks support, especially material and financial one, for its effective execution, which suggests that it may have any other - no official and/or institutional - different force driving the sector, while public policies appear as a shadow on the sector's performance.

Geopolitics, institutional analysis, public policies, tourism, ecuador

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140293629

IDR: 140293629 | УДК: 338.48

Текст научной статьи Tourism as geopolitical strategy: the institutional trajectory of tourism public policies in Ecuador

To view a copy of this license, visit

This study1 addresses the theme of tourism within the framework of the contemporary international division of labor (Marcussen, 1982; Kiljunen, 1989; Janoski, 2015; Grimberg, 2016), in particular what has come to be considered as post-industrial society (Touraine, 1969; Harvey, 1992) or labor and immaterial economy2 (De Negri; Lazaratto, 1992; Laza-ratto, 1992; 1993; Lessa, 2001). Particularly, it focuses on the question of how the tourism activity has acquired relevance3 in this recent context, on a global scale and particularly among developing countries. This lays on the discourse of rapid generation of employment and income and increase in the export agenda, to the point of being considered a structuring strategic axis (Eddy, 2016) transforming the production matrix of these countries infavorof tourism (Restrepo Quintero, 2014).

From the second half of the twentieth century tourism became a new sector of the world economy and a social practice with the expansion of capitalism, the development of technologies, the social and international division of laborandthe workers' demandforfree time (Araujo; Gelbcke, 2008). The great expansion of this sector over the last decades (Dias, 2003; Beni, 2 006) has generated expectations in the most diverse publics, and for many countries the sector has become a bet in terms of development (Ansarah, 2000). But, by assimilating diverse roles throughout the twentieth century, the State and its governments can establish goals, create structures, allocate resources, and provide expectations in different ways for the development of national tourism.

The empirical fact, however, is that the growing number and extent (in terms of the issues addressed) of tourism public policies is emerging as a common and recurring background, not only in developed countries but also in developing ones. In particular, Latin American countries have seen a true "wave1' (Pimentel, 2017) of expansion and institutionalization of tourism, through public policies, in the recent context (Harvey, 1992). Its adoption, however, is not always accompanied in a planned and critically reflected way, due to the characteristics and structural constraints of the country, but often occurs uncritically, being seen - as Cerqueira (2016) points out -as a quick and easy alternative to generate employment and income and increase exports.

The crucial point, however, is that even under the economic aspect (seen as an export sector), tourism does not always generate a trade balance surplus by virtue of (except in specific countries4) a total volume of tourist inflow (considering the inflows of foreigners and outflows of residents to other countries) are generally close, having a more prominent significance in the differential spending rates between inbound tourism and outbound tourism (Ouriques, 2005; 2008).

Moreover, studies on the tourism economic chain show that about 75% of tourism GDP is concentrated in the operating segments of the activity: airline companies, hotel chains, and travel agencies, which are, in general, and on a global level, dominated by large transnational business conglomerates based in developed countries (Bull, 1994). One implication is that tourism does not seem to be as profitable an economic activity as it promises, especially for poor countries (Vercellone, 2017).

Despite this, one witnesses a growing space dedicated to tourism as an increasingly relevant and even strategic economic activity in their national development agendas, almost always empirically effecting a change in their productive matrix in order to give more and more space to this activity (Eddy, 2016;

Pimentel, 2017; 2021). In a way, such phenomenon has been repeated in several countries, thus characterizing a global phenomenon, although its adoption in a more accentuated way is in the peripheral countries, mainly due to their low investment capacity and the low value that this industry requires.

In this sense, considering the emergence and institutionalization of tourism in the new world order of the international division of labor, we start from the following research question: how does the emergence, expansion and institutionalization of tourism take place in Ecuador, through its national public policies? The objective, therefore, is to map the institutional trajectory of tourism public policies in Ecuador over the last 30 years (1990-2020), from its normative, regulatory, and cognitive dimensions, in order to highlight how this "issue" acquires a status of "public interest".

We start from the assumption that tourism has assumed a growing role and relevance in contemporary Western capitalist societies and that this manifests itself in a more notorious way to the extent that its National States recognize it as a theme of public interest and integrate it in their agendas, discourses and actions. It is hoped that this study can contribute to the programmatic revision of cou rses of action adopted in tourism public policies, which eventually take the activity in an overvalued manner in relation to its contributive potential in generating employment and income in the economic-productive matrix of the country.

2 Geopolitics and Tourism

Geopolitics - the interface between power and space - as afield of social practices has always existed in the human universe (Lacoste, 1972). However, its importance was dramatically accentuated in the last quarterof the 19th century, when there is a deliberate process of reflexivity on the subject, emerging as an area of study, and more recently in the last 50 years. If in the beginning, geopolitical issues were more concentrated in the hands of the rulers - governors, emperors, feudal aristocracy, etc. -; in the last century, the situation has become more "democratized" as a new type of actors gained access to influence political decisions, for example large corporations (such as international car factories in developing countries). However, it has become more complex, polarized and multifaceted, as in the stable world of the feudal era power was exercised in a bidirectional (or more often unidirectional) way, in the modern world multiple actors emerge, with distinct capitals and with them spheres of influence, and power relations come to be redefined in a multidirectional network. The political power of National States, exercised by their governments, is now disputed (and interfered too) by "nonpolitical" actors, most of these "new" actors, large international corporations5.

From an economic perspective, in particular its production apparatus, tourism is embedded at the macroeconomic level in a new functional form (Dachary, 2015) of articulating and maximizing capitalism (Harvey, 1992), in which it operates in two ways: (1) increasing the circulation of capital between spaces and regions - including peripheral ones - thus increasing the possibilities of resource allocation and thus optimizing the differential advantages that can be exploited from the asymmetries between these regions; and (2) the inclusion within the productive and economic system - i.e. production, distribution and consumption - of a new class of leisure time-related products and services6 (Zuzanek, 2018; 2020a, 2020b), thus increasing the scope of the capitalist system through the introduction of new, typically non-productive products and areas (Briceno & Munoz, 2015). In other words, tourism becomes a symbol of accumulation even by the inclusion in the market (and the logic of working time and its rules) of free (and "unproductive") time.

In the macro-sociological context (Wal-lerstein, 1974; 2000), a new framework of international division of labor operates in the second half of the twentieth century, with the consolidation of post-industrial societies (Tou-raine, 1969) and the expansion of the service sector and the contraction of the industrial sector. It is in this context that tourism is inserted in this new world order, where, on one hand, the more developed countries absorb this activity, but selectively, especially the more technical and operational parts of this system, yet in a diluted way among all the other activities of their economic system; while, on the other hand, the peripheral countries incorporate it more markedly, because with a less diversified economic system and products of lower added value, this activity would be incorporated and accommodated in an easier way, still specialized in areas destined for tourism, due to the lower investment capacity in commercial and productive apparatus of the activity (Pimentel, 2020). Thus, in these countries, what would remain would be the exploitation of natural resources through international management equipment, capable of making the necessary investments in the transformation and exploitation of such resources (Arend, 1990; Pochmann, 1991).

Tourism has become an economically important "industry" and has been massively replicated in several countries around the world (Dachary, 2018). Such an economic activity has been adopted by countries, especially developing countries, as a form of development, as it does not require large investments (compared to other activities, such as the automobile orcell phone industry, innovation, etc.). However, tourism is a less profitable sectorthan manufacturing-intensive manufacturing, and even within the tourism sector, there are different levels of income according to the subsector of the tourism chain (e.g., most of the GDP (75%) stays with international hotel chains, tour operators and airlines, while restaurants, attractions, etc. -activities typically carried out in destinations-are less profitable) (Bull, 1994). Thus, tourism has been "pushed" into developing countries as a form of development, however, it can be an illusion if only the (plantation) pattern in which it is hegemonically preached is followed. In order to put it back on its (developmental) course it is necessary to make a more specific assessment and see the ways and (under what conditions) it can be emancipatory.

3 The Institutionalization of Public Policies in Tourism

Institutions are a central object of the social sciences, and for some authors are their own object of social sciences (Hughes, 1936). This is because they metonymically represent the three pillars of all social analysis: action, change and structure (Vandenberghe, 2010). In these social phenomena, the characteristics of permanence and collective behavior "meet in a particular way, so that the very form assumed by collective behavior is socially permanent" (Hugges, 1936, p. 180).

The 20th century witnesses the rise and centrality of this object of study, in its most varied forms. At least since Max Weber, various sociological studies have considered bureaucratic structures, such as ministries, businesses, schools, and interest groups, the result of striving for the formation of increasingly effective structures to fulfill the formal tasks attached to these organizations (Hall; Taylor, 2003).

In the subfield of institutional theory, this story can be told in three stages: from the old institutionalism, which extends from the 1930s to the end of the 1960s; the new institutionalism, which runs from the 1970s; and a third moment, from the 1980s onward, what maybe could be called "newest institutionalism", in which there is a theoretical and discursive fragmentation into localized concepts such as institutional work and institutional entrepreneur.

While the first phase tended to focus on institutions from their organizational aspect and the infusion of value into these structures -that is, for Selznick (1948) institutionalization is a "process", something "that happens to the organization overtime"; the new institutionalism embraces a more symbolic and culturalist perspective, grounded by a constructivist epistemological perspective, in vogue in the 1960s. According to Berger and Luckmann (2004), the process by which actions are repeated over time and take on similar meanings among actors is defined as institutionalization. Inthis sense, wewilltry to identify how the State, through tourism public policies, institutionalizes this activity7.

In the 1980s institutionalist theorists gave a new impetus to the field and laid the foundations for its contemporary discussion.

DiMaggio and Powell (1983, p.148) considered the process of institutional definition by the expansion of the degree of interaction among organizations in the field, by the emergence of domination structures and coalition patterns, and by a greater mutual knowledge among the participants involved in the same enterprise.

Scott (1995), for example, has systematized the various approaches according to their emphasis on normative, regulatory, and cognitive regulations. The approach that falls under the regulatory pillar has norms, laws, and sanctions as its legitimation basis. Under the normative pillar, legitimacy comes from group values and expectations. Finally, in the cognitive pillar, a set of shared knowledge legitimizes institutionalization.

Despite the much that has been discussed about public policies in general (Souza, 2006; Faria, 2003, 2005; Melo, 1996; Paiva, 2010), only recently has tourism policy been gaining prominence and being studied and evaluated in a systematic and intermittent way.

Studies in the area of tourism based on the assumptions of institutional theory are still recent and incipient (Song, Dwyer, Li & Cao, 2012; La-vandoski, Albino Silva & Vargas-Sanchez, 2014; Pimentel, 2014a, 2014b; Carvalho, 2015; Cintra, Aman-cio-Vieira & Costa, 2016; Falaster, Za-nin & Guerrazzi, 2017; Endres & Matias, 2018), being even scarcer when specifying the type of institutional theory strand, for example, historical institutionalism (Endres & Matias, 2018; Estol, Camilleri & Font, 2018; Falaster, Zan in & Guerrazzi, 2017;

Carvalho, 2015) and especially when applied to the topic of tourism research (Falaster, Zan in & Guerrazzi, 2017; Pimentel, 2016b; Pimentel, Carvalho & Bifano-Oliveira, 2017; Pimentel, Carvalho & Pimentel, 2017;

Some works, in the international field and also in the regional (Latin American) and local (Brazilian) context, contribute to the studies in which institutional theory is used in tourism, either in the theoretical or empirical sphere (Table 1).

The institutional approach in the study of the state is interested in issues such as the institutionalization of procedures and the consolidation of government actions, the effect of political institutions on the behavior of actors or the content of political decisions (Arretche, 2007). Understood as what governments decide to door not to do (Dye, 2009), public policies can have their themes, formats, objectives, and effects diversified (Pimentel; Pimentel, 2019) not only when comparing different national states, but as the roles assumed by a given state vary in the course of its history (Kliksberg, 1998).

In the wake of these systematization processes and drawing on their contributions, Pimentel (2011) applied the synthetic framework established by Scott (1995) in the study of tourism at the municipal level in Brazil, being one of the first studies and that effectively dialogued with institutional theory in this sector. Based on Berger and Luckmann's (2004) conception of institutionalization: "the process by which actions are repeated over time and take on similar meanings8 among actors"

(Pimentel, 2011 : 84), the author develops a protocol based on the following categories: (a) the characteristics that constitute them, namely: 1. objectives; 2. expected effects; (b)

the institutional reference arrangement, defined by: 3. position in the organizational structure; 4. proponent; and 5. Resources (Pimentel, 2011; 2014).

Table 1 - Summary of recent studies on institutional theory in tourism

|

Authors |

Context /Level |

Type of Study |

Contributions |

|

Lavandoski, Albino Silva e Vargas-Sanchez (2014) |

World / International |

Theoretical review |

They analyze tourism with respect to studies on: the environment, entrepreneurship, innovation, technology, social responsibility, institutional arrangements, governance, public policy and political trust, often focusing on the articulation between various stakeholders in a specific context |

|

Song et al. (2012), |

World / International |

They propose the broadening of the adoption of the institutional perspective in studies on tourism economics in order to extend the existing knowledge frontiers on the subject |

|

|

Carvalho (2015) |

Brazil / National |

Theoreti-ca 1-empirical |

They observe the conjuncture of formation of the national tourism public agenda (Brazil) based on historical institutionalism |

|

Falaster, Zanin e Guerrazzi (2017) |

Brazil / Local |

ro Ф Ф or E Ш |

They propose institutional theory as a framework for analyzing the image of a destination and its relationship between tourists and the local population, grounded in sociological institutionalism |

|

Endres e Matias (2018) |

They use historical institutionalism to analyze the trajectory of the main actors that are directly involved with the development of tourism |

||

|

Le et al. (2006) |

Vietnam / Nationa |

They analyze the factors that interfere in the adoption or rejection of environmentally friendly practices in hotel organizations |

|

|

Wilke e Rodrigues (2013) |

- |

They start from the premise that the norms and regulations created and consolidated in society make up a set of institutional forces that put pressure on organizations to seek legitimacy in their sector |

|

|

Garcia-Cabrera e Duran-Herrera (2014) |

- |

They discuss how the effects of an economic crisis stimulate tourism companies to generate innovation in order to remain competitive |

|

|

Gomes, Vargas-Sanchez e Pessali (2014) |

Spain / Local |

They analyze the interaction of the tourist trade, emphasizing the concepts of entrepreneurship, governance and public policies |

|

|

Cintra, Aman-cio-Vieira e Costa (2016) |

- |

They analyze the configuration of the organizational field of tourism |

|

|

Araujo e Mal-heiros (2013) |

Brazil / Regional |

They analyze the evolution of regional development (South Region of Brazil) using the organizational model of the Local Productive Arrangement (APL) among firms and other institutions |

|

|

Aureli e Baldo (2019) |

- |

ro Ф Ф as •a LU |

They analyze the role of private organizations, focusing on the administration of Convention Bureaus, with particular attention on the diversity among the members that form the entity and the need for integrated information about the actions at the institutional level |

|

Fazito, Scott e Russell (2016) |

Brazil / Local |

Observes the process of social construction of the discourse on sustainability in a biological reserve |

|

|

Silva (2017) |

Brazil/ Regional |

Analyzed how the public power, in its various spheres, historically established stimuli to the tourist activity, from an economic approach and its reflexes in the institutionalization of municipal tourism in Brazil |

Source: own elaboration based on the material reviewed.

In his view this instrument would be useful in capturing elements of the institutionalization process related form the normative aspects, given by the very institutionality of the institutional arrangement, for example: regulatory, via the sector's own legislation, its normative acts and formal elements; as well as cognitive, by the social construction and sharing of meanings underlying the processes (Pimentel, 2014). We then used this conceptual-methodological framework to guide the study.

4 Methodology

This research is of an empirical nature and based on secondary data from official sources of the Repub lie of Ecuador, in its three branches (executive, legislative and judiciary), plus strategic institutional documents of the Ministry of Tourism (policies, plans and action programs). Its object of study is the "normative acts", at the national level, of the Federative Republic of Ecuador, specifically related to the tourism sector, being here these tourism normative acts (ANT) understood simply as tourism "public policies" (PPT).

For the identification and collection of data, this research resorted to searching the official press of that country, since this would be responsible for communicating the institution of the normative acts and, therefore, when they are published, they would clothe themselves with the official status they are entitled to. By official press, here we take the main means and channels of communication of the three powers - executive, legislative and judiciary - through which, necessarily, at some stage of the process, whether downstream or upstream, such normative acts go through; in general, being, at least, at the end, filed in such registers (or database). Thus, we initially took the data from the "Official Registry"9 repository of the Republic of Ecuador, as the exclusive source for the research, to which, in a second moment, data from the institutional repository of the "National Assembly"10 and the "Ministry of Tourism"11 were added for consultation, due to the scarcity and/or incompleteness of the data12 originally found in the "Official Registry"13.

The study covered the period of the last 30 years (1990-2020). A total of 431 documents containing the word "tourism", "turistico(a)" and "turis" were found in the aforementioned official repositories. All documents found were downloaded and saved in Google Drive (Phase 1). After this stage of search and collection of initial data, we moved on to the stage of classification and screening of the material, whose goal was to verify inconsistencies, eliminate redundancies and produce the refinement of the sample (Phase 2), thus reaching its final form. For the execution of this phase, the documents were first counted, and all of them were reviewed, individually, to verify if they were really documents tourism about normative acts on tourism.

This way, the documents were classified into four different groups: a) ANT (tourism normative acts) that mention the search term and deal specifically with the tourism theme, b) ANT that mention the search term, but do not have specific tourism content, c) ANT of other levels "Municipal and/or State" outside the scope of the research, and, finally d) repeated ANT. After sorting the documents (Phase 2), the final sample of the analysis (Phase 3) was consolidated. From the total of 431 (100%) documents originally identified mentioning tourism, 122 (28.3%) were not specifically about tourism (although they mentioned this word in some part of the text), 85 (19.7%) referred to municipal and/or state ANTs, 1 (0.23%) document was repeated14

and finally 223 (51.7%) were actually about tourism.

After identifying and quantifying the nor-mativeacts atthe national level in Ecuadorfrom 1989 to 2020, we moved on to Phase 4, which was to organize, classify, and analyze each normative act according to the PPT organizational analysis method used by Pimentel (2014). The script below summarizes the proposed systematization (Pimentel, 2014, p. 274):

-

1. Identify the main tourism public policies;

-

2. Analyze the means used by govern-mentsto institutionalize tourism public policies. For this purpose it was sought: a. the institutional arrangement by which tourism policies are outlined, defined by: i) position in the organizational structure; ii) proponent; iii) investments.

-

b. the constituent characteristics, namely: i) objectives; ii) expected effects.

In possession of such analysis, reconstitute the agenda of tourism public policies, seeking to group public policies into periods with distinctive characteristics, defining an organizing principle and the expected effects in each period.

After the survey, classification and grouping of the data, we proceeded, specifi cally, to use content analysis as a method of analysis and treatment of the data collected on Public Tourism Policies/PPTur in Ecuador to trace the meanings of how the legitimating and propelling discourses of these policies were constituted starting in 1990.

Thus, over the last century, the growth and multiplication of actions of the Ecuadorian State in relation to tourism public policies has been witnessed, and the set of structures and mechanisms created overtime constitute today an institutional apparatus represented by the Ministry of Tourism, which from 2000 began a process of decentralization, with periodic national plans, programs and projects, which are carried out in a decentralized manner, through articulation and participation with involving local governments and other entities to promote development and selfmanagement (Carrion; 2003; Serrano, 2011). Policies at the provincial and cantonal level must be articulated with policies at the national level, that is, with the policies developed by the Ministry of Tourism. Therefore, the decentralized, provincial and cantonal public bodies are not free to relay their own policies and projects, but must follow and implement - through their plans and projects -the national tourism policies, thus contributing to implement the guidelines of the national tourism policy (Cevallos, 2015).

Table 2 - Number of records according to source

|

Source/ Repository Description |

Official Register* |

National Assembly |

Turismo Ministry |

Subtotal |

|

Period* |

2001-2020 |

2009 a 2018 |

1989 a 2017 |

1989 a 2020 |

|

Total of Normative Acts / NA |

9307 |

147 |

59 |

9.513 |

|

Total of Normative Acts / NA "tourism" as criteria of search |

344 |

28 |

59 |

431 |

|

Total of Normative Acts / NA with no real tourism contend ("no tourism") |

113 |

8 |

1 |

122 |

|

Total of Normative Acts / NA on municipal or state level ("no national level") |

85 |

- |

- |

85 |

|

Total of Normative Acts / NA repeated |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

|

Total of Normative Acts / NA with real tourism contend (sample) |

145 |

20 |

58 |

223 |

* The periods have different date among themselves because they have different data availability according to the each database.

Source: own elaboration based on the research data based on the data from Official Records, National Assembly and Ministry of Tourism.

-

14 These 3 initial categories were rejected and filed as they were outside the original scope of the research.

Table 3 -Summary of the evolution of the state apparatus, policies and mechanisms related to tourism in Ecuador from 1930-2020

|

Period |

Main characteristics |

|

Decade 1930 (first actions, Tourism Law) |

|

|

1940s (operative companies and creation of organizational structures) |

|

|

1950s (Emphasis on International Tourism - private tourism operation and the State assumes responsibility for promotion and infrastructure) |

|

|

1960s (Parks and tourism promotion) |

|

|

1970s (No actions on tourism) |

• The country has devoted itself to oil exploration. |

|

1980s Community Tourism |

|

|

1990s Tourism Institutionalization |

|

|

2000s Institutionalization and |

|

Period strengthening of tourism

Main characteristics administrative independence (Caiza & Molina, 2012);

-

• In 2001, state policies were established for the sector, and the National Government declared the development of tourism as a national priority. Thus, MINTUR promotes actions so that tourism becomes the most important currency generator of the national economy (National Plan forTourism Competitiveness, 2012).

-

• In 2002, the Organic Law of Tourism was created, which regulates the tourism sector.

-

• In 2007, the Strategic Plan for Sustainable Tourism in Ecuador was created (PLANDETUR, 2020), and sustainable tourism has become a key element in the country's agenda.

-

• PLANDETUR (2020) is led by the Ministry of Tourism (MINTUR) and aims to coordinate public, private and community actions for the development of tourism, aiming at equity, poverty reduction, competitiveness, decentralization and sustainability, promoting the economic and social development of the country (MINTUR, 2007).

-

• In the period 2008-2011 aII actors, from small traders to large companies, had a strong presence in making decisions of transcendental importance (Caiza & Molina, 2012).

-

• In 2008, the Government of Ecuador, in the first term of President Rafael Correa (2008-2011), declared Tourism as a State Policy (Caiza & Molina, 2012). In this way, several plans have been introduced into the government's agenda to make tourism one of the strategic sectors that contribute to the change of the productive matrix.

-

• In 2009, the Comprehensive Tourism Marketing Plan for Ecuador was published (PIMTE, 2014).

-

• With the reform of the Constitution in 2008, a process of decentralization began for the Autonomous Decentralized Governments (Regional, Provincial and Parish) (Serra no, 2011).

-

• The country's brand was changed in 2010 to "Ecuador, loves life".

-

• The Comprehensive Tourism Marketing Plan for Ecuador is created (PIMTE, 2010-2014).

-

• In rafael correa's second term (2012-2015), an analysis of the functioning of government policies at national, provincial and cantonal level was made, with emphasis on tourism development policies at the cantonal level, in order to better understand how they are applied and which actors are present in this process.

2010s to 2020

Professionaliza

tion

-

• Ecuador's National Development Policy is called the Buen V'rvir Plan, which focuses on outlining the country's socio-economic development guidelines for the period 2013-2017, where tourism is a strategic sector to drive the transformation of the production matrix (SENPLADES, 2013);

-

• According to Renato Ceva Iios, tourism training coordinator at the Ministry of Tourism, ecuador's Strategic Plan for the Development of Sustainable Tourism 2020 (PLANDETUR, 2020) has been in disuse since 2014. Instead of PLANDETUR 2020, some projects and programmes were created forthe period 2014-2017. These MINTUR Plans (2014-2017) have five basic pillars: Security, Destinations and Products, Quality, Connectivity and Promotion15.

-

• In 2017, under Lenin Moreno Garces, tourism is a central axis of development;

-

• In 2017, the National Tourism Policy is created, which aims to convert Ecuador into a tourist^powerhouse (MINTUR, 2019)

Source: own elaboration based on the bibliography revised (Serrano, 2011; Pietros, 2011; Caiza; Molina, 2012; Oliveira; 2016; Saant; Caires, 2017).

Since the 2000s tourism has been incorporated as a strategic axis for economic development in Ecuador because of its ability to improve the inflow of foreign exchange, reduce the fiscal deficit, and generate new jobs (Ordonez, 2001). In this way, tourism gains centrality in State policies (MINTUR, 2019), which recognizes it as a sector of importance, giving emphasis in a particular way, to community tourism (Saant; Caires, 2017; Bravo et al., 2021). The country seeks to develop tourism in a sustainable way, as it recognizes that sustainability goes beyond the environmental issue, and is also related to social and gender equity, with citizen and local participation, with an emphasis on decentralization (Ordonez, 2001; SENPLADES, 2013; Ramos, 2016).

Tourism has acquired priority in the productive matrix of the country, from the foundation that the Ecuadorian economy is basically dedicated in the extraction of natural resources, is intensive in primary goods and re-source-based manufacturing, not generating great returns, and tourism is an important activity in the increment of production (SENPLADES, 2013). According to MINTUR (2019) tourism in the last 6 years has had an average growth of 5%, in 2018 the direct contribution of tourism in Ecuador’s GDP was 2.8%, and the total contribution was 6%, even in a study by CEPAL (2020), in 2019 tourism represented around 10% in the country's exports of goods and services.

The main normative and governing instrument of tourism public policies in Ecuador, currently underway, is its national tourism plan, which have as a general proposal the integral development of society, generating quality of life for its population, emphasizing happiness, cultural and environmental diversity, harmony, equality, equity and solidarity16. Among its objectives is the promotion of the transformation of the production matrix, in which tourism is incorporated as the most important activity in the change process17. Specifically, in relation to Goal 10: Promote the transformation of the production matrix, it proposes to promote the transformation of production structures with the objective of promoting import substitution and productive diversification. Thus, this objective aims to encourage "national production, systemic productivity and competitiveness, knowledge accumulation, strategic insertion in the global economy and complementary production in regional integration" (SENPLADES, 2013, p.292).

This goal mentions the synergies that must exist between social equality and economic dynamics and proposes the creation of new industries and new sectors; the promotion of public investment, public procurement and the promotion of private investment; the promotion of import substitution, disaggregation and transfer of technology, endogenous knowledge and the prioritization of diversified national production.

In this proposal for Buen Vivir socialism, according to the plan, the goal is to achieve the transition - from a neoliberal country to a socialist country - which also means a change in production relationsand in the mentality of the citizens. It therefore seeks balanced and sustainable growth in contrast to neoliberal trends that seek opulence and infinite economic growth. In this sense, it proposes a state of regulation and planning that gives priority to the distribution of resources and where the interest of the people is the supreme order. On the other hand, the plan refers to the modification of power relations, that is, "the transformation of the state is expressed in the appropriate distribution of power through decentralization processes that, in turn, are part of democratization" (SENPLADES, 2013, p.17). Another relevant aspect is the emphasis given to democratization and citizen participation in the fulfillment of the proposed objectives, where such participation has a major importance to the nationbuilding of the country.

5 Tourism Public Policies/PPTur in Ecuador

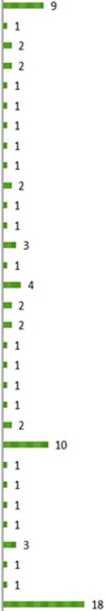

When the temporal distribution of ANTs in Ecuador is verified (Figure 2), it is observed the vast majority (93.72%) of these NA concentrated in the recent period, from the decade of 2010 to 2020, with emphasis on the years 2019, 2017 and 2020, respectively with 32.28%, 16.59% and 13.0%. This confirms that there is an ongoing process of accentuation of the relative importance of the tourism activity by the State, as previously identified as the strategy of change in the productive matrix of the country (SEPLANDES, 2013). In addition, it suggests a continuity of public policies due to the relative stability and maintenance of a certain regularity, particularly seen from 2014 and extending over the period 2014 to 2020.

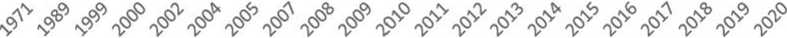

Analyzing the months in which the normative acts were published, we see that February, March, April, July and December, are the months with the highest frequency, i.e., at the beginning and end of the year, which may suggest a coincidence with the beginning of the legislature and the end of fiscal years, and the limit period for commitment of resources, respectively (Figure 3).

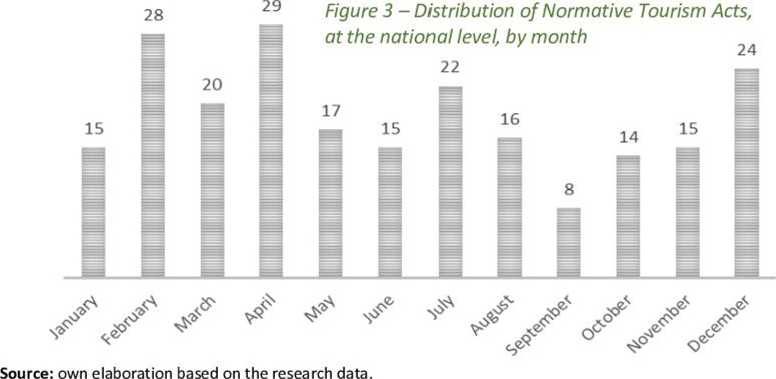

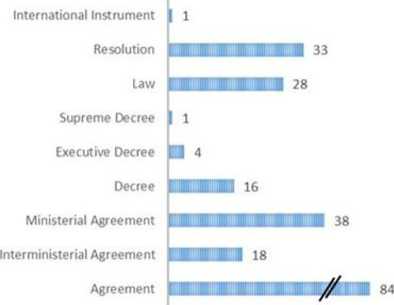

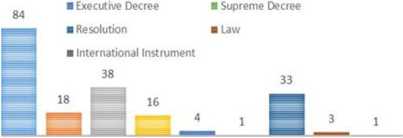

Of the 223 normative acts analyzed: 84 are Agreements, 18 are Interministerial Agreements, 38 are Ministerial Agreements, 16 are classified as Decree, 4 as Executive Decrees, 1 as Supreme Decree, 28 are Laws, 33 are Resolutions, and 1 is an International Instrument (Table 4).

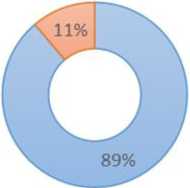

Regarding the institutional arrangement (Table 4), the ANTs perpetrated by the executive represent 89% of the total, followed by the ANTs of the legislative branch with 11% (Figure 1). We did not identify any ANTs concerning the judiciary. This difference is, in a way, expected, since it is up to the executive to implement the State's actions, giving, for this, an outlet for its demands through normative acts of different types and purposes. On the other hand, the lower relative performance of the legislative power suggests a lower participation of this power in the regulation of this sector, which can be due to an eventual "greater" economic freedom of the agents to explore the sector or else a lack of "perception" and assimilation, by this power, of the economic and social importance of tourism in the country.

-

□ Executive

-

□ Legislative

Figure 1 - Distribution of Tourism Norma tive Acts, at the national level, per year

Institutional Arrangement

Source: own elaboration based on the research data.

16 17 |

Иа

4 - ° о 5 4

1111 11112 3

— — — — Я — — — —

Figure 2 - Distribution of Tourism Normative Acts, at the national level, by year Source: own elaboration based on the research data.

|

Table 4 - Types of normative acts according to the type of bureaucratic organization |

|||

|

Grouping/Type of bureaucratic organization |

Types of Normative Acts |

Total |

% |

|

Executive Decree |

4 |

1,79 |

|

|

Supreme Decree |

1 |

0,44 |

|

|

Decree |

16 |

7,17 |

|

|

Ministerial Agreement |

38 |

17,04 |

|

|

Normative Acts of the Executive |

Inte rmin iste rial Agreement |

18 |

8,07 |

|

Branch, at the national level |

Agreement |

84 |

37,66 |

|

Law |

3 |

1,22 |

|

|

Resolution |

33 |

14,79 |

|

|

International Instrument |

1 |

0,44 |

|

|

Normative Acts of the Legislative Power, at the national level |

Law |

28 |

12,55 |

|

Normative Acts of the Judiciary, .. , -iiU . Not found 0 at the national level |

0 |

|

Subtotal Normative Acts 223 |

100% |

Source: own elaboration based on the research data.

Figure 4 - Distribution of Normative Tourism Acts, at the national level, by type

Source: own elaboration based on the research data.

Besides the prominence, in terms of their relative importance, of the executive's ANTs (Figure 4), an asymmetric distribution among their types is observed. While 21.97% refer to primary ANTs, i.e., universally binding, the vast majority (79.03%) are secondary and administrative NA of the public administration, such as agreements and resolutions. This suggests that the measures taken by the State have, in the majority, an ordering, instructive and disciplining character, placing conditions whose force of compliance is less restrictive and more discretionary by the agents.

Another important issue refers to the specific preponderance of agreements as the most frequently used ANT modality (37.66%), which is even higherif weconsiderthe modality of ministerial and interministerial agreements, totaling (62.77%), in these 3 types, the most used type of ANT. Next come resolutions (14.79%) and only in third place are laws (12.55%). When analyzing, qualitatively, the agreements, it is verified, for example, that they are instruments used, mainly, in two ways: a) one regarding the proposals of potential partnerships or an initial step in relation to cooperation with another country on a specific theme; or b) between agencies and ministries of the national public administration itself in order to standardize and parameterize matters, or regulate the realization of joint actions.

-

■ Agreement ■ Interministerial Agreement

-

■ Ministerial Agreement ■ Decree

Figure 5- Distribution of Normative Tourism Acts, at the national level, by type, focusing only on the Executive branch

Source: own elaboration based on the research data.

Ecuadorian Navy

Technical Secretariat of the National System of Professional QuaWications

National Secretariat of Public Administration

President of the Republic and Ministry of Tourism

President of the Republic and Director of the Official Registry

President of the Republic

Internal Revenue Service • Tax Policy Committee

Ecuador National Customs Service

Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Human Mobility

Ministry of Tourism

Ministry of Tourism - Ecuadorian Tourism Corporation* Executive body (Company) of Tourism at the federal level in... i 1

Ministry of Tourism and Ministry of Interior

Ministry of Tourism and Ministry of Environment and Water Ministry of Tourism and Ministry of the Environment

Ministry of Tourism and Ministry of Government, Police and worship

Ministry of Tourism and Ministry of Public Health

Ministry of Transportation and Public Works

Ministry of labor and Employment and Ministry of Tourism

Ministry of Government, Ministry of Tourism and Ministry of Health

Ministry of Gove mment and Ministry of Tourism

Ministry of Government and Police and Ministry of Tourism

Ministry of Culture and Heritage

Ministry of Environment, Ministry of National Defense, Ministry of Tourism and Ministry of Transportation

Ministry of Environment

Ministry of Industries and Productivity - Quality System Undersecretariat

Ministry of Industries and Productivity • Quality System Undersecretariat Ministry of Industries and Productivity

Ministry of Production, Foreign Trade, Investment and Fishing ■ Undersecretariat of Quality

Ministry of National Defense

Ministry of Urban Development and Housing • Technical Council for Land Use and Management

Ministry of Economy and Finance - Economic and Productive Sectorial Cabinet

Coordinating Ministry of Production, Employment and Competitiveness - Production Sectorial Council Directorate General of Internal Revenue Services

Directors of the National Agency of Regulation and Control of Land Transport, Traffic and Road Security National Competencies Council

Counci of Planning and Development of the Amazon Special Territorial District

Board of Directors of the National Agency for the Regulation and Control of Land Transport, Traffic and Road Safety GalapagosSpecial Regime Government Counci National Congress

Galapagos, Cafiar, Pastaza, Manabi and Imbabura Assembly National Assembly and General Secretariat National Assembly

Figure 6 - Distribution of Tourism Normative Acts, at the national level, by their position in the Organizational Structure

Source: own elaboration based on the research data.

Of the 223 normative acts analyzed 89% (total 198 acts) are from the Executive, and 11% (total 25) are from the Legislative. Of the 198 policies prepared by the Executive: 84 are Agreements, 18 are Inter-Ministerial Agreements, 38 are Ministerial Agreements, 16 are classified as Decree, 4 as Executive Decrees, 1 as Supreme Decree, 3 are Laws prepared by the Executive, 33 are Resolutions and 1 is an International Instrument (Figure 5).

When only the ANTs of the executive are analyzed, it can be seen that most normative acts were prepared by the Ministry of Tourism with a total of 106 documents. Next, the Presidency of the Republic has a total of 27 normative acts, followed by the National Assembly with a total of 18 acts, and the Directory of the National Agency of Regulation and Control of Land Transport, Traffic and Road Safety with a total of 10 acts. The remaining bodies have fewer normative acts as can be seen in Figure 6.

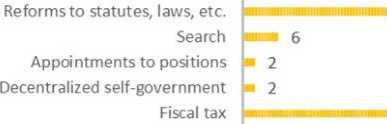

From the 223 normative acts analyzed we identified that 53 had as their objective the "Creation and approval of norms and regulations", followed by 49 acts with the objective of "Delegation of functions and responsibilities", and 28 with the objective of "Regulation of commercial activities related to tourism" (Figure 8).

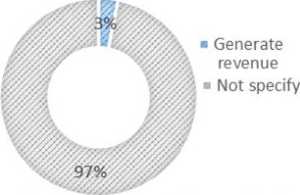

Considering all the normative acts analyzed, none of them presented any type of economic resource destinated to their execution. Of the 223 acts, 216 did not specify if the proposed policy would have some kind of burden, and 7 indicated that the normative act would generate revenue (Figure 7).

Figure 7 - Distribution of Normative Tourism Acts, at the national level, according to the Resources committed for their execution

Source: own elaboration based on the research data.

In order to delve deeper into those normative acts in which the resource was not specified, we analyzed from its objective whether this resource was omitted. In this way we generated three other categories: "there will be no burden" in the case where the normative act referred to a standard or regulation and did not really generate any type of burden; "there will be a burden" in the case where it indicated, for example, the need for a trip by a public representative, but the burden was omitted; and "there may be a burden" in those cases where the proposed normative act indicated some type of expense.

Covid-19 ■ 2

™™"™ 8

Community Tourism and Popular and... 3

Transportation/Signaling

Regulation in protected natural areas

Regulation of commercial activities related...

Appointments and representations in... n™ 7

Delegation of functions and responsibilities

Creation and approval of norms and...

Travel Authorization 1

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Figure 8 - Distribution of Normative Tourism Acts, at the national level, according to their Objectives

Source: own elaboration based on the research data.

This deepening allowed us to reach the result that of the 216 normative acts in which the resource was not specified, 194 normative acts actually there would be no burden when it comes to the creation of norms, law reforms, statutes, delegation of functions, etc.; in 15 normative acts we identified that their implementation would generate some kind of burden (there will be burden) with salary, research, holding events, public works, etc. salary, travel, exoneration of tourist tax, exoneration of tariff, and exoneration of taxes; and 7 normative acts we identified that there may be burden, such as a redistributive policy, feasibility study, road control, etc. (Figure 9).

-

• Will be a burden W • Will be no burden ■ May be a burden

^,90%

Figure 9 - Distribution of the Tourism Normative Acts, at the national level, according to the Type of Resource Source: own elaboration based on the research data.

6 Discussion: tourism public policies and geopolitical analysis

What data show in terms of geopolitical analysis? Geopolitics, in classical terms, deals with the strategic conduct of the State aiming to reach a better position in the international scenario. In Ecuador, we can witness an ongoing process of geopolitical action in terms of tourism, due its recurrency and stability over the years and specially in the current century.

First of all, we have identified that the number of normative acts has increased more than 200% on the last 2 decades (after 2,000). This is an indicator which - allied to other observations (Eddy, 2017) - shows us that there is a conduct of the State in terms of considering tourism as a national strategy, in order to make a change in the productive structure of the economy, putting tourism as one of the main sectors to be fostered.

The second point is that Ministry of Tourism, as the main actor performing the normative acts, confirms the classical stream on geopolitics studies in which State actors are determinant in order to push forward geopolitical issues. Moreover, when we analyze the contend of the docu ments - for example, federal constitution, tourism national plan, Buen Vivir national master plan, among others - we confirm that tourism is pursued as a strategy to generate income and jobs. Thus, "selling the country" in the international tourism market is a strategy to increase the national GDP in the economy and occupy a large number of people. Even when one considers the agreements made by the legislative, one still can see that different actions are performed in order to engage with nations (externally) and sectors (internally) aiming to create easy conditions to run tourism business.

However, if the number of acts and their legislation (ordering issues) abouttourism has increased. On the other hand, we cannot affirm that there are feasibly. It is because the resources related to the implementation of that policies are not specified or even are not existing themselves, which makes that the proper condition of its execution will be unassured.

At this point, we came up with a paradox situation - typical in developing countries -where is expected that the tourism flow - special international one - increases, but the necessary operational actions (more than legislation, programs and plans) to perform the activity are not taken by the State. Thus, this strategy of national development can be seriously threatened in in a double sense: on one side, tourisms is a lees profitable activity than other industries and betting excessively on it -for example, forgetting other strategic sectors or in a monopolistic sense - can represent a kind of plantation economy and a return to the colonial era (Hall, 1994). On the other side, it is very necessary that the National State be capable to ensure the resources -economic and material ones - needed to perform the activity, inside the tourism sector itself. Otherwise, it can become just one more unaccomplished task and loose one more passport to development (De Kadt, 1984).

7 Conclusion

This work aimed to map the institutional trajectory of tourism public policies in Ecuador in the last 30 years (1990-2020), seeking to highlight how this "issue" acquires a status of public interest.

From the analysis of the normative acts over time we have identified that the normative acts on tourism have had a greater growth in the last two decades, just when tourism is incorporated as a strategic axis for national economic development. Most of the ANT are generic, are agreements, and do not provide resources for their implementation, which suggests that there is no direct implementation of the issue.

Regarding the actors, most of those involved are from the executive power (Presidency, MINTUR, and other ministries). The Ministry of Tourism, is the main actor responsible for approximately 47% of the actions. On the other hand, it is worth noting the participation of the National Assembly (even if in a generic way) in the incorporation of the tourism theme in their speeches.

In this way, the study indicates that the ANTs seek to achieve better business performance, foreign exchange generation, and employment. In addition, the data confirm the idea that the PPTUR in Ecuador have become a theme of relevance and priority for public authorities in what is relative to the amount of ANT that has been published over time, however what is verified is that they are superficial in terms of a real application of initiatives and actions, in this way the theme of development, despite appearing in some ANT, is isolated and not applied.

It is hoped that this work can contribute to future research that aims to study tourism public policy planning and its potential economic and social implications.

Список литературы Tourism as geopolitical strategy: the institutional trajectory of tourism public policies in Ecuador

- Adu-Ampong, E. Divided we stand: institutional collaboration in tourism planning and development in the Central Region of Ghana. Current Issues in Tourism, 20 (3), 295-314, 2017.

- Agnew, John (2003[1998]). Geopolitics: re-visioning world politics. Taylor & Francis e-Library [Routldge]: London & New York.

- Ambrosie, L. M. Myths of tourism institutionalization and Cancún. Annals of Tourism Research, 54, 65-83, 2015.

- Araújo, N. De F.; & Malheiros, D. A participação das mulheres na política institucionalizada do Distrito Federal: Um olhar sobre atuações e repercussões no turismo sustentável. Revista Cenário, 1(1), 108-121, 2013.

- Arnaiz Burne, S. M. & César Dachary, A. A. (2009). Geopolítica, recursos naturales y turismo: una historia del Caribe mexicano. Editora de la Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario de la Costa.