Tourism councils as a voice institution in Brazil

Автор: Silva Juliana Ferreira Da, Gomes Bruno Martins Augusto, Pessali Huscar Fialho

Журнал: Сервис в России и за рубежом @service-rusjournal

Рубрика: Актуальные вопросы международного сотрудничества в сфере услуг

Статья в выпуске: 4 (96), 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

In Brazil, after the Federal Constitution of 1988, with the redemocratization process, municipal councils, including those of tourism, promote social participation in decisions about public policies. Thus, this work aims to analyze the institutionalization of voice in the legal norms and in the development of the activities of municipal tourism councils of state capitals of Brazil and the Federal District. It was identified that interaction in municipal tourism councils is characterized by the predominant presence of business associations and the public sector. With regard to policy formulation, the councils show a certain passivity, leaving the public sector in charge. There is little debate about plan evaluation and ways to improve implemented actions. The councils' debates revolve, above all, around infrastructure and event promotion actions to improve the destination's economic competitiveness. It was also found a low average participation in the meetings of representatives of the Legislative Branch and other bodies of the Executive Branch, despite the legal provision. We conclude that the use of a more active voice can be achieved with the recognition, by the councilors, of the COMTURs' function as spaces to use their voices and to influence the directions of tourism policies. And Hirschman's (1973) approach on the choices between voice, exit and loyalty, although still little used among researchers in the field, allows us to advance in the understanding of tourism public policies.

Councils, public policies, voice, tourism, brazil

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140261087

IDR: 140261087 | УДК: 338.48 | DOI: 10.24412/1995-042X-2021-4-32-47

Текст научной статьи Tourism councils as a voice institution in Brazil

To view a copy of this license, visit

In Latin America the debate on participatory processes that aim to integrate citizens in public policy decisions gained ground since the late 1970s (Araujo, 2011; Nobre, 2004). In Brazil, the Federal Constitution of 1988 a hallmark of the country’s re-democratization, gave room to institutionalized fora designed for citizens’ participation – such as policy councils, participatory budgets, public hearings and consultations. Some of those participatory innovations, in special tourism councils, have been integrated to tourism policy making.

Policy councils in Brazil may operate at different federation levels: national, state or local (municipal). They are supported by legislation, which establishes their specific roles. Some are aligned on those three levels with a national policy, as it happens with health councils, while other may result from local initiatives. In general, they are conceived as spaces for capturing demands and conciliating interests of different social groups, allowing citizens to have a bigger share on discussions and decisions of collective interest (Lüchmann, 2008). Nowadays, councils are seen as undeniable achievements in support of a stronger democratic society, influencing the production of public policies that are at least exposed to a wider range of social interests (Almeida; Ta-tagiba, 2012).

The first National Tourism Council was established in the 1960s by the military dictatorial government and it was explicitly selective: its members were a small group of finger-pointed businessmen and bureaucrats. The Federal Constitution of 1988 created the basis for social participation. Tourism councils could also spread to the state and municipal levels with a concern to being more inclusive. This would allow more voices from society to be heard, dormant or repressed questions to surface in constructive ways, and that refractory positions could be avoided or revised. However, it is still common to observe in this councils the dominance of businessmen and bureaucrats. Such state of things drives discussions mainly to the more immediate economic aspects of tourism, leaving aside both long-term development issues such as, socio-cultural and environmental problems, and more diffuse interests of many others affected by the activity. Thus, a better understanding of this interaction space is relevant because of the medium and long-term implications for the development of tourism in a region and its impacts on affected people with diffuse interests.

Participatory processes aim at facilitating the voice, and discouraging both indifference or submissive loyalty to the status quo, and exit or renunciation. But do municipal tourism councils act accordingly? Do they respect and encourage participation? What have they accomplished, or failed to accomplish in this direction?

These questions can be addressed with the lenses of the exit, voice and loyalty approach proposed by Albert Hirschman (1973). According to Hirschman, people respond in mainly three different ways to organizations that are expected to cater for them: exit (abandonment of the relationship), voice (political action, expression of ideas) and loyalty (renouncing preference based on commitment). Based on Hirschman’s approach, this paper analyses the institutionalization of voice in the legal rules and in the activities of the municipal tourism councils (COMTURs) in the Brazilian state capital cities and in the Federal District of Brasília.

In addition to this introduction, the article is organized in four sections. Section 2 presents Hirschman's approach and its application in tourism. Section 3 explains the methodological procedures adopted. Section 4 comes with the results and discussion, followed by some final considerations.

Theoretical framework

Tourism policies are actions that aim at the formulation of guidelines, planning, promotion and control of tourism activities of a country, state, region or city (Hall, 2008). In order to make decisions about these policies more democratic, tourism councils seek to integrate stakeholders linked to both the public sector and civil society. Their interactions are expected to affect policies and, thus, tourism development (Gomes, 2018).

In order to better understand such interactions, we frame the problem with Albert Hirschman's (1973) approach. In his book "Exit, voice and loyalty: responses to decline firms, organizations and states," Hirschman addressed the behavior of people toward organizations that propose to serve them, especially when expectations are not fulfilled. Hirschman saw three types of responses: exit, voice and loyalty.

Exit means giving up and abandoning the relationship. This reaction shows dissatisfaction with the other party, avoiding or interrupting a direct conflict. It may come with a search for other organizations as a result of frustration, for several reasons, with the previous one. In addition, exit can be encouraged in order to reduce internal protests expressed through voice, which may be convenient for a local government or other interested party in the relationship (Hirschman, 1973).

Voice can be sound by individuals or groups. A single person can complain directly to the provider of a service or organization, in one case, or collective actions such as petitions, pressure group activities, or other forms of social mobilization can emerge, in the other case (Dowding, 2015).

The democratic political system must have as basic elements, according to Gehlbach (2006), the possibility of voice and exit. The regular ballot is a common exit mechanism. In this case, citizens exit by not voting for incumbent representatives on government. For Delimatsis et al. (2019), this shows a preference for changing the certainty of frustration for the uncertainty of improving services with new representatives, and also the significant barriers that stand in the way of influencing incumbent offices. Both elements may lead to loyalty, which manifests itself as a factor that compels agents to stay in the organization or to postpone their exits.

Loyalty is the renunciation of a preference in favour of a commitment. It stands between voice and exit, expected to occur when there are obstacles to exit or significant costs to moving to an alternative organization (Hirschman, 1973). Loyalty can also be a result of positive experiences that bring about trust in the organization and the expectation of future improvements.

heard and their demands met. They also argue that loyalty can increase responsiveness, as loyal people are more likely to be heard (ibid). However, marked loyalty can grow into a lack of opportunities to exit (John, 2016). In these situations, voice may become the most desired behavior. If ineffective or not used, the result can be silence or conformity – a kind of discontent loyalty.

Exit crosses off other possibilities, whereas loyalty still enables voice Silva et al. (2017). The authors (ibid) observed that exit is used not only when society is indifferent to making political decisions that affect it, but it is also used by the State when decides for inaction. Voice, even if timidly, is exercised when citizens participate in political decisions. Loyalty, in its turn, is understood by the authors as a shared responsibility of society and the State: while society must remain committed, the State must be loyal in order to achieve the purposes demanded by democracy (ibid).

Citizens and business firms can also exit the public sector by leaving the territory (Dowding, 2015). The costs of this option, however, are usually high or even prohibitive. Voice thus become an attractive option, even when the State holds a monopoly on the service.

We shall call institutions the emerging patterns of interaction that, once established, mould future interactions (Hodgson, 1988; Pessali, 2015). Gomes (2018) proposed an exit, voice and loyalty matrix to study such institutions in tourism. The matrix has been adapted here in order to focus on the use of voice in tourism councils. Table 1 shows the categories and subcategories selected to inform this study.

Table 1 – Adapted Matrix exit, voice and loyalty1

|

The use of voice categories |

Subcategories |

|

Collective action by businesspeople |

Common business agenda |

|

Interaction among bureaucrats |

Participation of other public agents in the tourism council |

|

Negotiation |

Cooperation |

|

Coordenation |

Tourism Planning in execution that guides priority actions |

|

Importance of tourism in the public sector |

Direct public action in favor of tourism |

|

Tourism Fund in operation |

The first category is collective action of businesspeople It refers to their ability to organize interests and act accordingly, which includes influencing government decisions (Bianchi, 2007). In tourism, collective action can be observed through their capacity to build and present a common business agenda, granting the public sector a clear view on priorities (Gomes et al., 2020). Presenting a common business agenda can occur by means of closed or open institutions (Doctor 2016). To the purposes of this study, closed institutions do not allow citizens participation or scrutiny. Individual appointments with closed doors, private phone calls or club meetings illustrate the case. They give wide room for corrupt and privileged practices (ibid). Open institutions that allow citizens participation, such as policy councils, fit much better with democratic practices, making

1 Source: Authors, adapted from Gomes (2018)

ideas and interests subject to wider assessment.

Negotiation, third category, is a notion that permeates everyday life, whether in a commercial transaction or in family and labor relationships (Roloff et al., 2003). Negotiation is based on communication and interaction in which those involved create understandings and agreements that define the interdependence of the parties (ibid). One would expect to find negotiation as a regular practice in the democratic context of interaction in councils (Gomes et al., 2020).

Cooperation is a relevant ingredient once interdependence is realized in negotiation, for those involved need each other to achieve their goals, even when they diverge. Cooperation can be defined as the joint action of people or groups in pursuit of a collective end that may or may not favour those who cooperate (Pessali, 2015). According to Beritelli (2011), in the case of tourist destinations, cooperation is central for sustainable planning and implementation, and for the coordination of the public sector. The author (idem) argued that cooperative behaviour is favoured by mutual trust and by reinforced understanding among agents through communication. Active voice, thus play a central role in the decision-making spaces in tourism.

Finally, the importance of tourism in the public sector unfolds in two subcategories: direct public action in favour of tourism and an active tourism fund. Velasco (2016) highlights the public action that is oriented to tourism which starts from the relational and rational standpoints. The relational view has as its object the decision-making process of some agents so that their demands prevail over collective ones, emphasizing the performance of individuals and groups, politics and institutions. The rational view focuses on technique, planning and in the improvement of the processes in order to approach the problems and propose solutions. There are several areas in which tourism operates that often go well beyond the market action. Direct public action is relevant therein, in an attempt to prevent or correct failures caused by markets, or to provide a different institutional solution (Costa, 2015) in order to guarantee policies that contemplate social interests.

A tourism public fund, for instance, is an important tool in such direction (Gomes et al., 2020).

The next section presents the nature of the data collected and the materials and methods used for their treatment and analysis.

Materials and methods

A qualitative approach based on documentary data is used. Legislation and minutes of COMTURs meetings were our main sources.

The COMTURs originally selected were those in, São Paulo, Brasília, Salvador and

Manaus. They were chosen because they hold in their respective regions the largest simple sum of the number of jobs in the accommodation and food catering sectors (Ipea, 2016). This is a proxy indicator of the relevance of tourism activities. Due to the lack of data, especially the meetings minutes, the selected capitals of the Northern (Manaus) and Northeast (Salvador) regions were replaced by the capital with the second largest indicator (Porto Velho and Recife).

Minutes dated between 2013 and 2020 were collected, comprising two mayor terms. In addition, 2013 is the year in which the Brazilian Tourism Map was officially launched (Ordinance No. 313/2013 of the Ministry of Tourism)2. The

Map is a guiding instrument for the national government to develop sectorial and local policies, and it explicitly evokesa running local tourism council for a municipality to take part in those policies (Brasil, 2013). In total, eight minutes of each COMTURs were analyzed. The exception was Porto Velho, which had only three 2019 minutes available. Three of the main legal norms of each council were also selected for analysis – creation laws, regulatory decrees and internal bylaws.

The data collected from the documentation set were tabulated for each COMTUR based on the categories shown in Table 1. Table 2 shows how the content was placed into our categories and subcategories.

Table 2 – Characteristics considered for t he content categorization of the analyzed laws a nd minutes

|

The use of voice categories |

Subcategories |

Aspects |

Analysed Content |

|

Collective action by businesspeople |

Common business agenda |

Manifestations submitted jointly that transcend the interest of the represented organization |

Minutes |

|

Interaction among bureaucrats |

Participation of other public agents in the COMTUR |

Number of representatives of other Executive agencies and Legislative chamber established in the rules and attendance at the COMTURs meetings |

Laws and Minutes |

|

Negotiation |

Cooperation |

Manifestations that address partnerships and joint efforts between COMTURs and other organizations |

Laws and Minutes |

|

Coordenation |

Tourism Planning in execution that guides priority actions |

Statements about planning instruments |

Minutes |

|

Importance of tourism in the public sector |

Direct public action in favour of tourism |

Formal competences of the COMTURs and actions for the tourism development |

Laws and Minutes |

|

Tourism Fund in operation |

Manifestations on the tourism fund |

Minutes |

We also looked for verbs that could suggest propensities towards either active or passive voice used in the statements that deal with the councils’ attributions in the legal rules. The model proposed by Bassani (2018) was used. It contains verbs related to the direction of the voice and which give evidence of the attitude exercised by the agent at the COMTURs meetings. According to the model of the aforementioned author, after counting the verbs, the percentage is made, and it is verified the tendency to use the voice recommended in the legal rules.

Finally, we also looked into participation in the councils, with a focus on who the members are and which relevant social group they represent. This helps identifying which groups have been given room for voice. The following section presents a brief description of the councils, the codification carried out, and shows the results of the investigation.

Results

The legal documents selected provide information regarding the aims, competences, nature, composition and the functioning of meetings. All of them lay down the council’s collegiate link with the municipal administration, either with the mayor's office (São Paulo, 19923), or directly with the local tourism agency Curitiba, 2006 4,5,6; Brasília, 20107; Recife, 20098; Porto Velho, 19999 10). They also address the collegiate duties as for contributing to the proposition and implementation of the municipal tourism policy or plan. The councils analyzed vary in their final legal attribution: some are consultative and advisory (Curitiba, 2006; São Paulo, 1992; Brasília, 2010), some are deliberative (Curitiba, 2006; São Paulo, 1992; Porto Velho, 1999), one is also propositional (Brasília, 2010), and one is also normative (Porto

Velho, 1999).

Cooperation, as expressed in the related laws, come about as a combination of efforts among municipal authorities, civil society and businesspeople in favour of incentives and the development of tourism (Curitiba, 200911; São Paulo, 1992; COMTUR Distrito Federal, 2015; Recife, 2009). Only the norms from Porto Velho COMTUR do not address this matter.

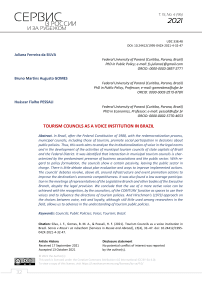

The minutes of the meetings record 16 cooperative actions among different groups. Figure 1 shows the corresponding agents involved.

The cooperative actions linking the council and universities involve research and research projects. Actions linking the council and other municipal agencies, mostly involve joint actions for holding events. The organizations with representatives in the councils also cooperate with each other to raise funds to the Municipal Fund of Tourism and to promote actions in order to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, cooperation actions were observed between COMTURs and the community for holding events and between COMTURs and representatives of the Legislative chamber, especially with the local congresspersons that take part in the Mixed Parliamentary Committee in Defense of Tourism, in order to increase the resources earmarked for the Tourism Fund.

Fig. 1 – Cooperation actions signed by municipal tourism councils

Such cooperative actions support a scenario of active negotiation and interaction in tourism councils. The biggest set of actions involve members of the councils for research, specific projects (about COVID-19 and fundraising), and events promotion. Actions with other groups are less frequent and robust.

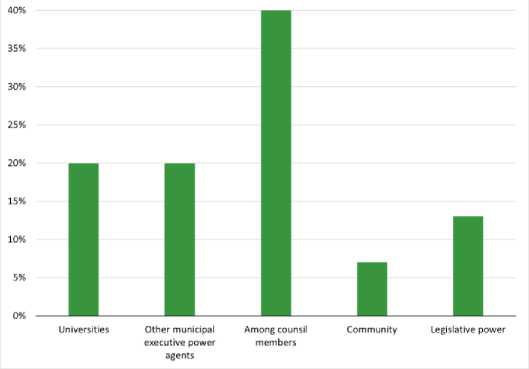

As for the presence and interaction among bureaucrats, it is necessary to show first that the COMTURs have representatives from both the Executive and Legislative branches, from different offices in the administration. The numbers of government representatives established in the rules of the COMTURs are presented in Table 3.

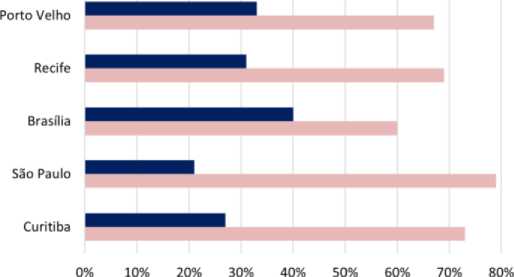

Representatives from the Executive branch outnumber those from the Legislative branch. Brasília’s COMTUR has no seats at all for a local legislature member. Figure 2 shows the number of seats set by law and the average attendance observed per meeting for government representatives.

Table 3 – Normative provision for representatives from Executive and Legislative branches

|

COMTUR |

Normative Provision |

|

|

Executive branch |

Legislative branch |

|

|

Curitiba São Paulo |

9 |

3 |

|

10 |

1 |

|

|

Brasília Recife |

10 |

0 |

|

16 |

1 |

|

|

Porto Velho |

6 |

1 |

-

Figure 2 shows that attendance to the meetings by government representatives is much lower than expected in accordance to what is established in the law. This holds true for both branches of government In Porto Velho, for example, the Executive branch holds six seats in COMTUR, but three was the average attendance. As for the representatives from the Legislative branch, average attendance was under one per meeting.

With regards to the content of the manifestations during the meetings representatives of public agencies focus on exposing the activities developed by their agencies. This shows that the interaction among bureaucrats in COMTURs seems less concerned with proactivity in proposing new fronts for joint activities, which could strengthen tourism and the public sector agencies themselves, and more with some kind of accountability or showcasing.

As for the legal guarantees for voice to citizens and civil organizations Curitiba and São Paulo did not present such guarantees, unlike Brasília, Recife and Porto Velho. Brasília allows for a third representative per organization, with the right of manifestation but not of voting (COMTUR Distrito Federal, 2015). Recife determines that, when appropriate, the council can invite people, entities or institutions to participate in its sessions or to submit reports on matters under debate (Recife, 2009). Porto Velho allows the participation of agencies or any other interested associations that work in the tourism sector.

The COMTUR from Brasília has an honorary president, representative of a private organization, who shares the presidential role with the council president. The position is temporary and rotative. Sharing in the leadership role may have a circular causation effect in which the commitment and concern with the quality of the deliberations from members from the private sector will increase their use of voice, which in turn increases commitment.

Direct action in favor of tourism activities is mentioned in the norms as within the scope of the councils. The COMTUR of Curitiba is bound to propose plans and legal instruments, promote activities and supervise its budgetary resources (Curitiba, 2007; Curitiba, 2009). The COMTUR of São Paulo is responsible for drawing guidelines, proposing solutions and developing tourism programs (São Paulo, 1992). The COMTUR of Brasília has the task of drawing guidelines, helping local tourism development and check the application of relevant legislation (Brasília, 2010). The COMTUR of Recife must establish priority zones of tourist interest and enhance tourism integration in the Metropolitan Region of Recife (Recife, 2009). Finally, the COMTUR of Porto Velho is responsible for advising on the administration of tourist attractions and of areas with potential for tourism, in addition to approving and monitoring a calendar of events (Porto Velho, 200712,13).

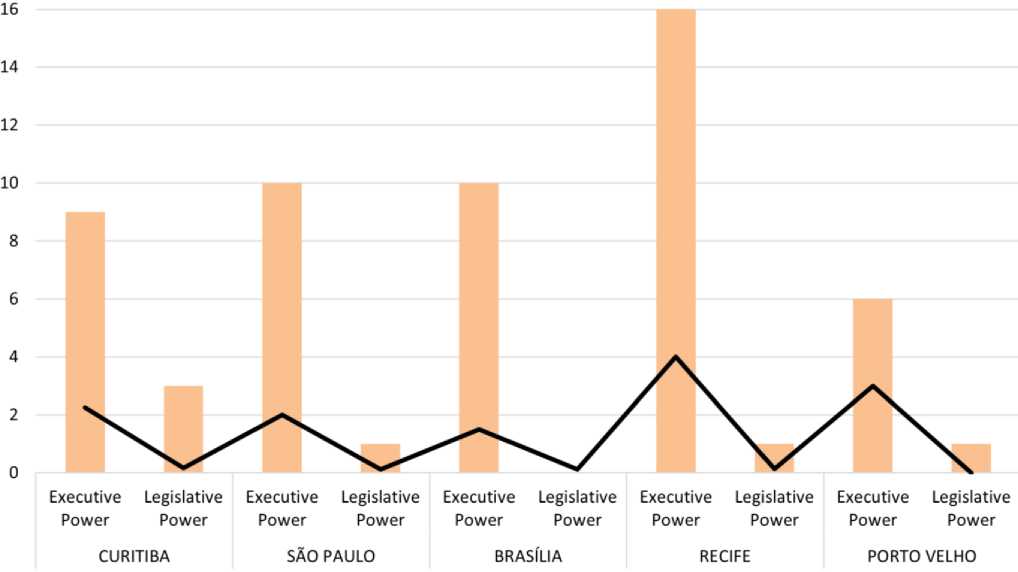

In the minutes of the meetings, 27 manifestations about government action were identified. Figure 3 shows the distribution of themes.

Attendance foreseen in the rule per meeting

Average attendance recorded per analyzed meeting

Fig. 2 – Presence foreseen in the rules and the average attendance of other public agents in tourism councils

-

12 Conselho municipal de turismo de Porto Velho (COMTUR). Regulamento do Conselho Municipal de Turismo de Porto Velho. Conselho Municipal de Turismo de Porto Velho, Porto Velho, 2007.

-

13 Porto Velho, RO. Lei Complementar nº 281, de 15 de maio de 2007. Dispõe sobre a reestruturação do Conselho Municipal de Turismo de Porto Velho – COMTUR, e dá outras providências. Legislação do Município de Porto Velho, RO, maio de 2007. Available at: https://leismunicipais.com.br/a/ro/p/porto-velho/lei-complementar/2007/28/281/lei-complemen-tar-n-281-2007-dispoe-sobre-a-reestruturacao-do-conselho-municipal-de-turismo-de-porto-velho-comtur-e-da-outras-providencias . Access: 26 November 2020.

Fig. 3 – Manifestations themes on public action in favor of tourism

Most manifestations address the themes of infrastructure, tourism promotion and events. As pointed by Hall (2008), these areas are mainly concerned with the improvement in economic competitiveness and the provision of public goods (considering that local citizens also enjoy the tourist sites).

In addition, Hall (ibid) argues that it is also necessary to educate, provide information and work towards reducing risks and uncertainties. Many tourism funds were started with such purposes, helping the public sector to reach farther.

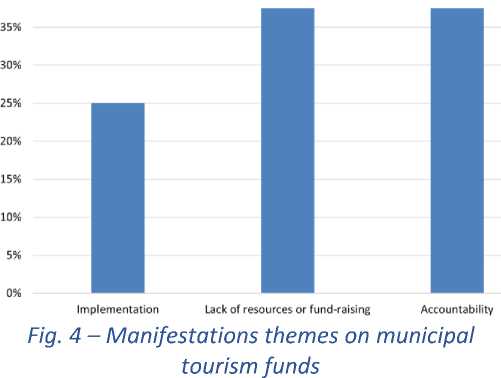

There were eight manifestations about tourism funds in the sampled documents. Figure 4 shows the overall results according to the main themes involved.

Accountability and the lack of resources or fund-raising are the main issues raised by the councilors. The COMTUR of São Paulo mentions the government’s account for the fund (COMTUR São Paulo, 2016a14), but no transfers have been made into it since 2013 (COMTUR São Paulo, 2016a). Some members gave their opinion on possible ways to raise funds and the Finance, Studies and Economic Development Commission was created in order to check the possibilities of changing its design (COMTUR São Paulo, 2017a15; 2020b16). The tourism fund from Porto Velho was established by law (Porto Velho, 2007) and discussions on the allocation of its resources were recorded in the minutes (COMTUR Porto Velho, 2019a; 172019b). This suggests some control of the collegiate on the tourism fund.

In Curitiba, the president of COMTUR from Curitiba commented about the application of a survey on the implementation of the fund in 2014 (COMTUR Curitiba, 201418). The matter was taken up in a meeting in 2016, but it was said that the issue would remain for the next city administration (COMTUR Curitiba, 2016b19). No further mentions were found on the topic.

As for the COMTUR of Brasília, there was a discussion about the need give account of the fund, but the fund is not being used (COMTUR Distrito Federal, 2016a20). And in the minutes of the meetings of COMTUR Recife, there is no mention about the fund.

The absence of a fund, or its inactivity may indicate that many decisions by the collegiate are not carried.

COMTURs in our sample have in their norms the provision to formulate plans and produce legal instruments to guide the local tourism policy (Curitiba, 2009; São Paulo, 1992; Recife, 196821; Porto Velho, 2007) and to propose projects to promote tourism activity (COMTUR BRASÍLIA, 201522). Minutes of three councils show discussions about the elaboration of municipal plans (COMTUR Curitiba, 2014a23; COMTUR Curitiba, 2016a24; COMTUR São Paulo, 2016a). The other three H- Brasília, Recife and Porto Velho – had no records of them. In general, it became noticeable that the councils debate little about tourism development and ongoing marketing plans. Debate on the evaluation of past plans is also rare. Members seem more keen to debate future tourism plans, mainly to check on which organization will be responsible for it (COMTUR São Paulo, 2016b), or to identify areas of interest to become their foci (COMTUR Curitiba, 2014).

The meetings seem to allow moments for all to expose ideas that seek to improve local tourism. The more specific function of coordinating and guiding the elaboration of plans, however, remains assigned to the public sector. Government representatives take the lead to answer questions about the plans and to present them to the council members when they are ready.

Many demands from businesspeople are presented individually by the members, especially in Curitiba. In the meetings, associations argue for the re installation of a receptive committee in order to improve services (COMTUR Curitiba, 2017) and complain about the parks’ infrastructure (COMTUR Curitiba, 2016). In Recife, there was an individual request recorded in support of walking routes in the city (COMTUR Recife, 2013a25).

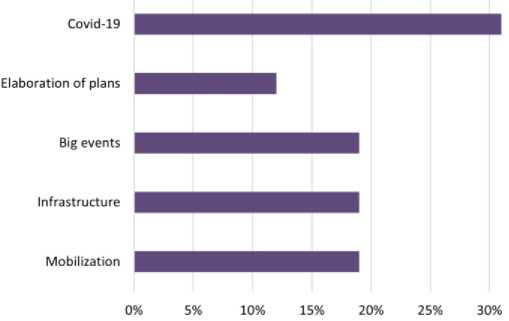

Manifestations on collective agendas and ideas were also found, mainly in the councils of São Paulo, Brasília, Recife and Porto Velho. They were 16 in total and their distribution by theme is shown in Figure 5.

Fig. 5 – Common themes in the business agenda

Most manifestations reflect the concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic. Big events, infrastructure, the need for joint mobilization, and the elaboration of tourism plans were the other main subjects discussed. The COVID-19 pandemic is widely known to have impacted heavily on tourism. Councilors were extremely sensitive to the context and seemed to converge on related issues such as requesting a timetable for businesses to reopen and defining criteria for the use of public transport during the pandemic (COMTUR Recife, 2020a26); suggestions about resuming tourism activities in conformity with health and safety protocols (COMTUR São Paulo, 2020b; COMTUR Curitiba, 2020a27); setting up working groups to feed discussions with updates on the pandemic situation (COMTUR Distrito Federal, 2020b28; COMTUR Curitiba, 2020a).

There is robust evidence that businesspeople in Brazilian tourism have a long-established habit of presenting their demands at councils meetings individually, without previous negotiation with their peers (Gomes, 2015; Alencar & Reyes Junior, 2017: Gomes & Pessali, 2018;). Thus, the chances of making each of them a priority to the public sector is reduced. As noted by Gomes et al. (2020), these situations leave the public sector in a difficult position to select priorities among items with little or no collective support. The Covid-19 pandemic, however, shows that a serious setback can spark greater synergy.

-

■ Passive voice Active voice

Fig. 6 – Tendency of the council rules in relation to voice

Lastly, Figure 6 shows the tendency of the verbs used to express the attributions of the councils in their legal norms.

In general, it was observed that the norms try to encourage the proactivity of tourism councils. The most frequent verb used in the set of documents analyzed, however, was “to propose” (22%), followed by “to approve” (16%), “to study and appreciate” (14%), indicating a predominantly propositional role for the councils. This seems to show that proactivity may not come easily, demanding more cooperation among private sector members and with the public sector.

Final comments

Municipal tourism councils aim to promote participation in policymaking by enabling a wider debate and the negotiation of interests among different groups in favor of tourism development. The behavior of councilors in interaction can be framed as voice, exit or loyalty, according to Hirschman (1973). This paper focused on the voice behavior and its institutionalization in the norms and meetings of tourism councils in five Brazilian capital cities: Curitiba, São Paulo, Brasília, Recife and Porto Velho.

Municipal tourism councils are predominantly occupied by representatives of business associations and the public sector. In relation to policy formulation, the councils seem to lack proactivity, leaving the public sector to coordinate and guide municipal tourism plans. There is little debate about evaluating past plans and improving ongoing actions. This happens in spite of legal norms that encourage the active voice of the councils.

Debates in COMTURs are mainly about urban infrastructure and the promotion of events, with a concern for increasing the economic competitiveness of the destination. Oher relevant activities to the public sector, such as providing information, education and reducing risks and uncertainties, are not mentioned. To some extent, resources from tourism funds could help to address them. but few councils demonstrate that they have resources, discuss about or account for them.

Legal norms point to cooperation among the members of the councils and with external parties. The studied documents show that cooperative actions are carried out mainly among members of the councils. Not all councils allow non-members to participate and speak in their meetings, and this may result in a circular causation. Members interact more, build trust among them and then cooperate (or the reverse), reinforcing their proximity for future cooperation. Non-members become increasingly distant from such circle. As democratic spaces, and to allows cooperation to reach a wider group, councils are expected to be inclusive with regards to the diversity of social interests. This can be achieved with the inclusion of groups other than business associations and government. They may include neighborhood associations, organizations that represent workers in the tourism sector and those with environmental and poverty alleviation concerns, or other groups meaningful to the local context considering the tourist vocation of the municipality, such as traditional communities.

The business associations come together to present their demands and to defend ideas when facing problems of a general nature, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, or big events that have a clear positive impact on a wider group of business interests. In such cases, there are collective and active manifestations.

Legal norms establish the participation of representatives of Executive and Legislative branches of local government. The studied documents show, however, that their attendance to the meetings is low on average. Their participation can be described mostly as accountability. This may indicate a certain lack of knowledge or of interest in the actions of the COMTURs, or a bureaucratic view of it, as if it were a fora for explaining and justifying decisions already made.

Many council members do not give their opinions during meetings, nor do they actively pursue cooperative actions s. Even so, they do not leave or stop interacting with the COMTURs. Their conflicts of interest do not spark debates and occasional negotiations, as one would expect in such a space and before institutionalized practices of fragmented action.

There seems to prevail a retracted voice and some apathy on the part of the members. Based on Hirschman's approach, voices in the sampled COMTURs focus on proposing, lying closer to loyalty than to exit. This is evidence of a significant gap to be reduced between what is established in the norms – more encouraging to an active voice – and what the records of the meetings show.

It is also worth questioning the extent in which the public sector, whose representatives preside over all sampled COMTURs, plays a facilitating role to stimulate debates and share responsibilities. Since citizens do not necessarily have complete training in a deliberative sense, a facilitator continually shapes and reshape the conditions for deliberation, and are therefore fundamental to participatory institutions. It may be the case in the sampled COMTURs, however, that the public sector feels comfortable with the current state of interaction patterns.

Accessing documents, mainly the minutes of the meetings, was more difficult than expected. This shows that Brazilian COMTURs have transparency issues to deal with. As a result, the time period of the sample was not homogenous and the sample smaller than it should be to allow more robust evidence and other hypotheses to be tested – such as changes in voice behavior related to changes in the city office.

In theoretical terms, it seems that the two models can be adapted fruitfully. Gomes (2018) model seems robust as a basis for studies with a focus on voice in a larger set of tourism councils (or even from other areas), while Bassani (2020) helps to link it to Hirschman's (1973) approach to the choices among voice, exit and loyalty in tourism studies. In the latter case, the approach seems useful not only if applied to policy councils, but also to other situations of standing

interactions, as it happens in or among employers' associations or communities, to name a few. In practical terms, the study provides useful information and analysis to the COMTURs, that may help to improve their design and operation as a voice institution. Future investigations may be dedicated to observing a larger set of councils or to include more categories of analysis in order to identify more patterns of behavior in the use of voice by tourism councilors.

Список литературы Tourism councils as a voice institution in Brazil

- Adnanes, M. (2004). Exit and/or voice? Youth and post-communist citizenship in Bulgaria. Political Psychology, 25(5), 795-815.

- Alencar, J. L. O., & Reyes Junior, E. (2017). Análise da rede de relagoes e sua influencia nas políticas públicas de turismo. Texto para discussao / Instituto de Pesquisa Económica Aplicada. Rio de Janeiro: Ipea.

- Almeida, C., & Tatagiba, L. (2012). Os conselhos gestores sob o crivo da política: balangos e perspectivas. Servigo Social e Sociedade, 109, 68-92.

- Araujo, C. M. (2011). Gestao pública democrática e democracia participativa no Brasil: Disseminagao dos conselhos de políticas públicas, no ámbito do turismo, no estado de Sao Paulo. Tourism & Management Studies, 1, 396-406.

- Bassani, C. P. (2019). Turismo, Direito e Democracia: uma análise dos bens democráticos nas leis dos conselhos municipais. 128f. MPhil Dissertation, Universidade Federal do Paraná.

- Beritelli, P. (2011). Cooperation among prominent actors in a tourist destination. Annals of Tourism Research, 3/38(2), 607-629.

- Bianchi, A. (2007). Empresários e agao coletiva: notas para um enfoque relacional do associativismo. Revista Sociologia Política, 28, 117-129.

- Costa, C. C. S. (2015). Instrumentos de Políticas Públicas do Turismo: uma análise empírica dos municipios portugueses. PhD Thesis, Universidade do Minho.

- Delimatsis, P., Kanevskaia, O., & Verghese, Z. (2019). Exit, voice and loyalty: strategic behavior in standards development organizations. TILEC Discussion Paper, 1-60.

- Doctor, M. (2016). From neo-corporatism to policy networks in Brazil: the case of lobbying for port reform. Revista Agenda Política, 4(1), 175-185.

- Dowding, K., & Hirschman, A. O. (2015). Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States". In: Lodge, M.; Page, E. C.; Balla, S. J. The Oxford Handbook of Classics in Public Policy and Administration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Flick, U. (2013). Introdugao á metodologia de pesquisa: um guia para iniciantes. Porto Alegre: Penso.

- Gehlbach, S. A. (2006). Formal model of exit and voice. Rationality and Society, 18(4), 395-418.

- Gilson, L. L., & Lipsky, M. (2015). Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service. In: Lodge, M.; Page, E. C.; Balla, S. J. The Oxford Handbook of Classics in Public Policy and Administration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gomes, B. M. A. (2015). Políticas públicas de turismo: interagao empresários-setor público em Curitiba sob a ótica institucional. Tese (Doutorado). Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba.

- Gomes, B. M. A., & Pessali, H. F. (2018). Salida Voz y Lealtad en las Políticas Públicas de Turismo: interacción entre empresarios y sector público. Estudios y Perspectivas en Turismo, 27, 336-354,.

- Gomes, B. M. A. (2018). Políticas Públicas de turismo e os empresários. Sao Paulo: All Print.

- Hall, M. (2008). Tourism Planning. Harlow: Pearson.

- Hirschman, A. (1973). Saída, voz e lealdade: reagoes ao declínio de firmas, organizagoes e estados. Sao Paulo: Perspectiva.

- Hodgson, G. (1988). Economics and institutions. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hoyler, T., & Campos, P. (2019). A vida política dos documentos: notas sobre burocratas, políticas e papéis. Revista Sociologia Política, 27(69).

- I nstituto de pesquisa económica aplicada (IPEA). Extrator de dados do setor de turismo, 2016. URL: http://extrator.ipea.gov.br/. Access: 16 April 2021.

- John, P., & Dowding, K. (2016). Spanning exit and voice: Albert Hirschman's contribution to political science. In: BianchI, M.; Franzini, M. (eds). Research in the History of Economic Thought and Methodology, 34B, 175-196.

- John, P. (2016). Finding exits and voices: Albert Hirschman's contribution to the study of public services. International Public Management Journal, 20(3), 512-529.

- Lipsky, M. (2019). Burocracia de nível de rua: dilemas do individuo nos servidos públicos. Brasilia: Enap.

- Lotta, G., Pires, R., & Oliveira, V. (2014). Burocratas de médio escalao: novos olhares sobre velhos atores da produjo de políticas públicas. Revista do Servigo Público, 65(4), 463-492.

- Lüchmann, L. (2008). Participado e representado nos conselhos gestores e no ornamento participativo. Caderno CRH, 21(52), 87-97.

- Miele, M., & Zylbersztajn, D. (2005). Coordenado e desempenho da transado entre viticultores e vinícolas na Serra Gaúcha. RAUSP, 40(4), 330-341.

- Nobre, M. (2004). Participado e Deliberado na teoria democrática. In: Coelho, V. S. P., & Nobre, M. (Orgs.) Participagao e Deliberagao: Teoria Democrática e Experiencias Institucionais no Brasil Contemporáneo. Sao Paulo: Editora 34, 21-40.

- Pessali, H. F. (2015). Nanoelementos da mesoeconomia. Curitiba: Editora UFPR.

- Pessali, H. F., & Gomes, B. (Org.) (2020). Instituigoes de democracia participativa: bens democráticos nos conselhos de políticas públicas de Curitiba. Curitiba: PUCPress.

- Roloff, M. E., Putnam, L. L., & Anastasiou, L. (2003). Negotiation skills. In: Greene, J. O., Burleson, B. R. Handbook of Communication and Social Interaction Skills. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Rua, M. G., & Aguiar, A. T. (1995). A política industrial no Brasil, 1985-1992: políticos, burocratas e interesses organizados no processo de policy-making. Planejamento e Políticas Públicas, 12, 233-277.

- Silva, F. R., Candado, A. C., Rodrigues, W., & Batista, W. L. (2017). Controle social: a dinámica da teoria da saída, voz e lealdade no contexto da administrado pública brasileira. Revista Emancipagao, 17(1), 108-125.

- Velasco-González, M. (2016). Entre el poder y la racionalidad: gobierno del turismo, política turística, planificación turística y gestión pública del turismo. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 14(3), 577-594.