Traditional tailoring technology as an ethnographic source (the case of eastern Slavic clothing in Southern Siberia)

Автор: Fursova E.F.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnography

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.45, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145318

IDR: 145145318 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2017.45.3.115-125

Текст статьи Traditional tailoring technology as an ethnographic source (the case of eastern Slavic clothing in Southern Siberia)

Thus far, ethnological studies have paid insufficient attention to the development and advancement of methods for the research of the real objects of material culture, museum collections, and in particular traditional clothing. In the 1920s, in the period of intense studies of the material heritage of the USSR nations and their local varieties, ethnologists focused on the ways of wearing, styles, and terminology of the traditional clothing (Grinkova, 1927; Danilin, 1927; Zelenin, 1991). G.G. Gromov (1966: 63– 76), in his textbook on the techniques of ethnological research, addressed the procedures and methods of field work, including identification of materials, motifs of decoration, and sewing-patterns. He did not focus on the techniques of clothing manufacture, such as seams or fabrication of separate units (collar, clasps, etc.), though he advocated making sketches of building techniques in descriptions of dwellings (Gromov, 1966: 59). G.S. Maslova, an eminent researcher of the Slavic traditional costume, proposed classifying the types of garment on the basis of their style, and for more exact classification, to consider fabric, manufacturing techniques, color, and decorative patterns (Lebedeva, Maslova, 1967: 193). Notably, such a criterion as tailoring technology was not well elaborated in Maslova’s works. Analysis of the techniques of processing and sewing deerskin, as well as of types and names of seams, was first performed by Russian ethnologists during the study of the traditional clothing of peoples of Siberia; they also

proposed a detailed program of ethnological research (Khomich, 1970: 104; Prytkova, 1970: 208).

Comparative-historical analysis of the traditional tailoring technology of the Eastern Slavic peoples in Siberia allows us to identify their cultural composition, to confirm or disprove hypotheses as to their possible origin, and to trace the migration-routes of the first settlers and those who moved to Siberia in the late 19th to early 20th century. Construction traditions—in particular, for types of sarafan (a women’s full-body garment)— have been described by us in detail earlier (Fursova, 2015a). This paper addresses the uses of manufacturing techniques for certain types of clothing (shirts) by the peasants of Southern Siberia in the late 19th to early 20th century in the context of ethno-confessional studies. The analysis was based on the typology of stitches and seams, and on their methods of graphic representation, adopted in tailoring technology (Savostitsky, Melikov, Kulikova, 1971: 104–111: Kryuchkova, 2010: 22–39).

Traditional tailoring technology implies methods of modeling clothes using the two-dimensional cutting elements by manually connecting them together, and also methods of processing of clothing details, which methods were passed across the generations and could have been culturally specific (along with the style* and the construction**). Tailoring was a typical female occupation, and every girl learned sewing techniques, names of stitches, seams, etc. from her mother and grandmother.

In this paper, we describe only one type of traditional clothing that was sewn manually from home-made linen fabric. According to the ethnological data, such clothing was worn in Siberia in the 19th to early 20th century by various population groups: Polyaki (‘Poles’) Old-Believers, Bukhtarma Kerzhaks, and migrants from Ukraine, Belarus, and southern parts of Russia. Clothing from these groups, in its archaic form, has survived in the museum collections of Barnaul, Krasnoyarsk, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Tomsk, and St. Petersburg. Natives of Siberia, including the Chaldons, the migrants from the northern parts of Russia, and later also some groups of Old-Believers (e.g., Dvoedans ), comparatively early began to use cheap Chinese and Russian fabrics and sewing machines, and to place orders at professional tailors. This paper focuses on the analysis of techniques for sewing the underwear (shirts) of the peasants who migrated to Southern Siberia from the Dnieper-Desna interfluve (Gomel, Chernigov, and Bryansk regions), the area which is also known in scientific literature as Pogranichye.

*The style pertains to the way the clothing is worn on a human body (either on the shoulders or on the waist).

**Clothing construction pertains to the cutting-details of which a 3-D model is created; construction is graphically represented in a sewing pattern.

Clothing “for the Kingdom to come”

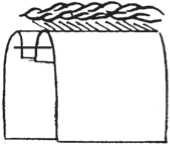

The most significant information for our research has been obtained through the study of the hand-sewing techniques practiced by the Old-Believer groups. The oldest features of the Old-Believer culture display certain old and even rather ancient realia, because the Old-Believers used to live in isolation and followed old traditions. In the 1970s–1980s, we discovered the burial costumes of the Old-Believers* and the custom of preparing a special set** from home-made linen fabrics. Burial clothes were not sewn with the vtachkyu** *or back-stitch, like the clothes for living people, but with the zhivulka (‘basting’) or fore-stitch. When sewing with a zhivulka stitch, it was forbidden to make knots on the thread: elderly women believed that knots, as well as cross-seams, might serve as obstacles on the way of a person to Heaven. An explanation for such customs was given by D.K. Zelenin, a famous researcher of the late 19th to early 20th century, who has recorded a peasants’ legend from the northern parts of Russia, that the deceased might have come back for the other family members: having seen his burial clothes sewn with non- zhivulka stitch, the deceased would allegedly like to take someone of the relatives with him (1991: 347). For that reason, the sharp end of the needle, which was used for sewing the burial clothes, should have been symbolically directed away from the sewer towards the deceased.

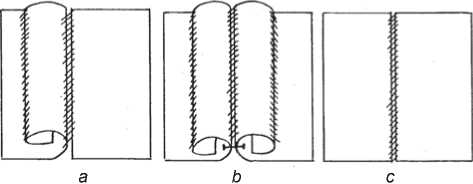

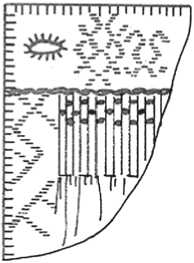

Another technique for sewing burial clothes was to joint the straight pieces of fabric butt-to-butt with a diagonal “over the edge” stitch (Fig. 1, c). However, our informants also mentioned the more detailed differentiation: burial clothes manufactured for future use were sewn “over the edge” (i.e. the edges of the fabric-pieces were attached butt-to-butt), but the seams on the clothes for the deceased were, surprisingly, made by zhivulka stitch. Different methods of burial-clothing manufacture apparently represented the distinction between the “good” deceased and the “bad” ones, who died suddenly or unnaturally (Ibid.: 352). So, clothing for “bad” deceased was distinguished by the special sewing technique. Notably, the ladder stitch is the most laborconsuming: in order to get with a needle into the edge of the joining pieces of fabric (one or two threads are grasped), an artisan needs special skill and proficiency. The basting stitch (Russian zhivulka (possibly derived from zhivoy (‘living’) or zhivo (‘quickly’)) is performed far more quickly, and can be applied for fast sewing of clothing for a suddenly deceased person. The zhivulka, “over the edge”, and vtachkyu stitches were used for sewing from linen fabric not only burial shirts, but also sarafans, pants, shrouds, and shoes (Fig. 2). The majority of burial sets investigated by us were sewn with white threads matching the color of the costume; red threads were found only in the clothes of the Polyaki Old-Believers. According to archive materials, in the mid-19th century, in the Arzamassky Uyezd, Nizhny Novgorod Governorate, red threads occurred in the burial clothes of only young women (Yavorsky, (s.a.)). However, the traditional clothing of the Polyaki Old-Believers always stood out among the many modest and ascetic costumes of other Old-Believer groups in Siberia and Russia in general, owing to its bright colors and rich decoration.

Shirts of the Polyaki from the Altai of the middle–second half of the 1800s

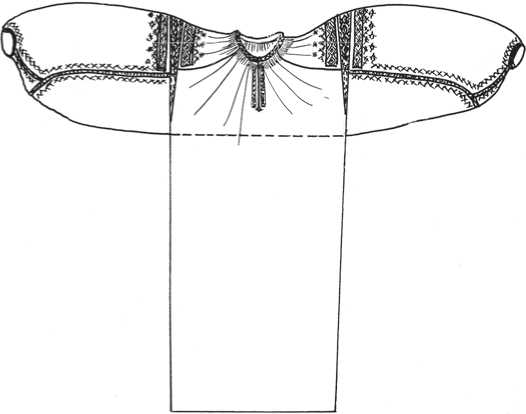

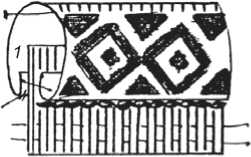

Of special interest are women’s polik * shirts (most likely, wedding dresses) of the Polyaki Old-Believers, sewn manually approximately in the middle–second half of the 19th century (Fig. 3). These shirts are also known as the shirts with kul sleeves, which were sewn with their bottom parts folded like envelopes so that openings for hands were executed without shirring (Fig. 4). The unwillingness of Old-Believers to make shirrs on clothes (except for collars) is explained by their beliefs about the sinfulness of pleats (Field Materials of the Author (FMA), 1978–1979). Below, we will discuss the techniques of connecting pieces of fabric, fabrication of separate units (collar, placket, cuff, etc.) of shirts; their construction features were described by us earlier (Fursova, 2015a: 136). Technology of colorful embroidery will also be described. In the early 20th century, Polyaki women wore shirts with unusual sleeves together with gored sarafans resembling the same clothing of smallholder groups from the Chernozem region and the Kursk-Belgorod frontier region (Alferova, 2008: 33; Tolkacheva, 2012: 168).

The technology of manufacturing linen shirts always corresponded strictly to the quality and especially the width of the fabric (40–42 cm). We have found three Polyaki linen shirts in museum collections: one short shirt without the stitched lower part, and two shirts with the stitched lower part. According to informants, the upper part was called chekhlik , kul , and the lower part stan , stanushka . Each part of the shirt was turned down and

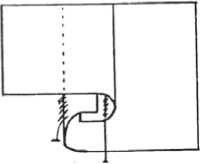

Fig. 1. Seams in the women’s polik shirts.

a, b – seams connecting the upper and lower shirt-parts with the stitches “over the edge”; c – seam connecting the shirtparts with the stitches “over the edge” (ladder stitch); d – felled seam with diagonal stitches.

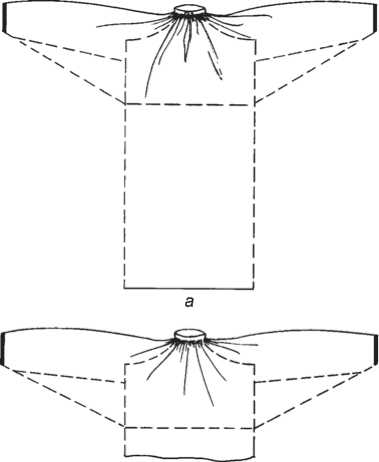

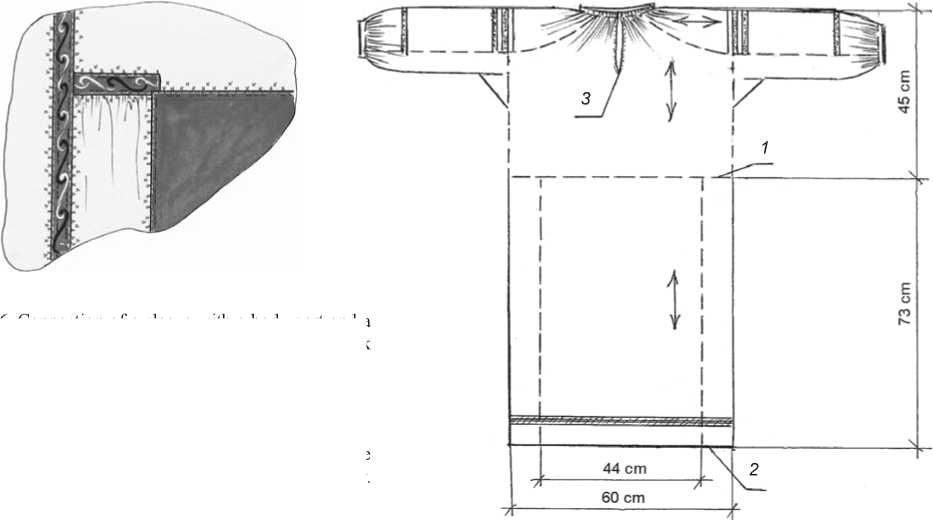

Fig. 2. Construction of the women’s linen burial shirt. The village of Bystrukha, Vladimirskaya Volost, Byisky Uyezd. 1902. Division of the East-Kazakhstan Regional Museum of History and Local History, GIK–IX.

a – front view; b – back view.

hemmed with a felled seam. Then, the hemmed edges were attached together with small diagonal “over the edge” stitches (see Fig. 1, a , b ). This method of attaching the two parts of a shirt together supports the hypothesis that such shirts originated from ancient unsewn types of outer- and underwear clothes (Moszynski, 1967: 446– 448). The bottom hem of a shirt was hemmed by diagonal stitches with a felled seam (see Fig. 1, d ).

In Polyaki shirts, the sleeves with polik inserts, extended with red strips, are attached together with open-

Fig. 3. Women’s white linen shirt. The village of Bystrukha, Vladimirskaya Volost, Byisky Uyezd. OSMLH No. 2351.

Fig. 4. Kul sleeve. OSMLH No. 2351.

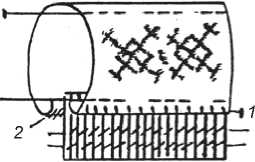

and closed-lap seams: the folded edge of one cloth piece is laid on the cut edge of another and stitched (Fig. 5, 6). Such stitches, executed in two or three lines, had both connecting and decorative functions. In the shirt from the “Novoselov’s collection”*, which is currently deposited in the Omsk State Museum of Local History (OSMLH, No. 2351), the first and the third lines of stitches are executed with white threads, while the second line is blue and has the form of alternating trines of stitches (see Fig. 5). Connections of sleeves with the body-part look simpler than the above-mentioned: they are executed in two lines, where one of the seams is decorative (see Fig. 6). The side-pieces are attached with double seams, as in the similar shirt with kul sleeves, from the collection of the Altai State Regional Studies Museum (Fig. 7). The typologically later shirts were sewn by craftswomen from store-bought fabrics using lap seams executed with back-stitches and diagonal stitches (Fig. 8). Such seams were designated by elderly women from the village of Topolnoye, Soloneshinsky District, Altai Territory, as “blind” (FMA, 1988/14). Lap seams became popular in the first third of the 20th century, when Polyaki women began to replace linen homespun cloth by store-bought fabrics, which were wider than the shirt width. In this case, when cutting the fabric-piece, the edges were turned down so as to prevent the unweaving of threads.

The wide collar, formed by the front and back cloths, and by polik inserts, was gathered through several threads, resulting in small folds around the neck (shirt No. 2351 from OSMLH shows eight threads gathering the collar).

The later Polyaki shirts sewn from store-bought fabrics had collars gathered through not more than three threads. Such execution of the neckline was made with zhivulka stitch. This technique distinguished the Polyaki women’s shirts from those of the Bukhtarma and most of the Uimon Old-Believers, who shirred fabric at the collar with a vtachkyu stitch (FMA, 1978, 1981; Fig. 9, 10).

Another specific technique of tailoring the shirts under study was the connection of polik inserts with sleeves, as well as connection of sleeve-details with each other, using a lace proshva insert, which was crocheted or hand-knitted. Similar techniques have been noted in the traditions of the Semeyskie Old-Believers from Trans-Baikal region, which (like Polyaki ) were deported to Siberia from Vetka near Gomel in the 18th century (Fig. 11). The sleeve-bottoms of linen shirts were edged with red strips or pleteshki -plaits attached by diagonal stitches (Fig. 12). The shirts made of store-bought or silk fabrics were also often decorated with plaits, but sleevebottoms were additionally edged with textile strips by the lap seams.

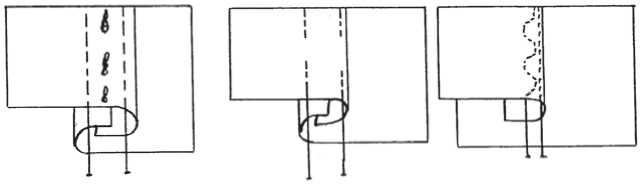

A collar represented a strip of textile, which was stitched from the wrong side with a felled seam using small invisible back-stitches, and from the right side it was turned down and stitched likewise (see Fig. 9). Such a method of attachment allowed the edges of fabric to be carefully concealed. The examined shirts from the Omsk and Altai local museums showed collars and plackets, which were stitched at the edges with a felled seam using red threads (Fig. 13). Such execution of collar-edges with red threads was aimed at strengthening the fabric (so that the detail maintained its shape) and at decoration. Apparently, this trend reflects the belief that harm to person’s health can be inflicted through the openings in the clothing. It’s no coincidence that our informants called this seam zamok (‘lock’), and used it also for the attachment of sleeve-parts (see Fig. 7). Geometric patterns on the polik inserts, collar, and at the joints of sleeves with inserts were embroidered using the verkhoshov, nabor, and counted-thread embroidery techniques, which G.S. Maslova considered the most archaic in the Russian handicrafts (1978: 41, 42). An Old-Believer women’s linen shirt with kul sleeves (Russkiy narodnyi kostyum…, 1984: 217), brought from the Narymsky Cossack settlement (of the former Semipalatinsk Governorate) to the Russian Museum of Ethnography, showed typological similarity to the Polyaki shirts (Fig. 14).

In terms of tailoring technology, the studied women’s shirts obviously pertain to wedding clothing and are close to the Polyaki men’s linen shirts, which are now kept in the “Novoselov’s collection” of OSMLH. However, the latter, unlike the polik women’s shirts, have a tunic-like design: the whole cloth is bent over the shoulders with a cutout neck and two side cloth-inserts. Men’s shirts have their structural seams additionally decorated with embroidered patterns and red strips. For instance, shirt No. 3134 from OSMLH demonstrates the following design: three pieces of the body-part, about 40 cm wide each, are sewn together with diagonal ladder stitch; upon these, red strips 4 cm wide are sewn, which are covered with meander pattern using chain stitch (Fig. 15). All other strips are also attached with lap seams, for example, at the joint places of sleeves with the side cloth-pieces. In a similar way, strips are sewn on the sleeve- and shirt-bottoms, and red gussets* are attached to the sleeves and the bodypart of the shirt (Fig. 16). In the shirt under study, sleeve-details are sewn together with a lap seam, as in the similar men’s shirt from the same collection (OSMLH, No. 3497). The

Fig. 5. Closed-lap seam.

Fig. 6. Open- and closed-lap seam.

Fig. 7. Women’s wedding shirt. Altai Mountains region, Tomsk Governorate. The second part of the 19th century (Istoki…, 2011: 47).

Fig. 8. Closed-lap seam.

Fig. 9. Shirt’s collar. The village of Sekisovka, Vladimirskaya Volost, Altai Mountains region. Late 19th century.

FMA, 1978.

3 I

Fig. 10. Shirt’s collar. The village of Belaya, Verkh-Bukhtarminskaya Volost, Altai Mountains region. Late 19th century. FMA, 1978.

Fig. 11. Semeyskie Old-Believers’ shirts. The village of Bichura, Bichursky District, Republic of Buryatia, 1920s. FMA, 1977.

Fig. 12. Edging the sleevebottoms with pleteshki -plaits.

Fig. 13. Execution of a collar and a placket.

Fig. 14. Old-Believer women’s shirt. Narymsky Cossack settlement (of the former Semipalatinsk Governorate). Middle 19th century. (Russkiy narodnyi kostyum…, 1984: 217).

Fig. 15. Wedding dress of an Old-Believer bridegroom. The village of Sekisovka, Zmeinogorsky Uyezd, Semipalatinsk Governorate, middle 19th–early 20th century. (Russkiy narodnyi kostyum…, 1984: 217).

placket in such shirt is usually located at the left; neckline and collar are edged with decorative pleteshki -plaits made of red linen threads. The plaits were also used for making buttonholes of conical shape (one buttonhole in each shirt); the buttonholes are also held by such plaits. These men’s shirts, like women’s shirts with the kul sleeves, are decorated with sophisticated embroidery using the verkhoshov , nabor , and counted-thread techniques. As has been already shown in our papers, according to their origin, these shirts of the Altaian Polyaki groups can be correlated with the clothing of migrants from Bryansk, Gomel, and Chernigov regions, descending from the culture of Ancient Rus (clergy clothes) and medieval Western Europe (clergy and noble clothes) (Fursova, 2015b: 162).

Shirts of Vetka migrantsfrom the Gomel region of the late 19th century

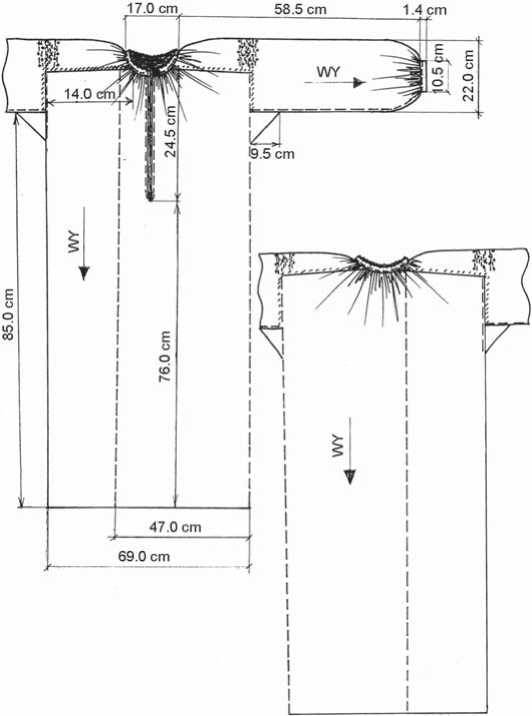

Migrants from the Gomel region settled down in the village of Irbey, Irbeysky District, Krasnoyarsk Territory, in the late 19th century. They originated from the village of Neglyubka, near Vetka settlement, which was the common ancestral homeland of the Polyaki from Altai and the Semeyskie from Trans-Baikal. The collection of Krasnoyarsk Regional Museum of Local History contains non-polik shirts (wherein inserts are connected with sleeves) of the Gomel migrants (KMLH, No. 6861-1, 6861-15). The Irbey shirts tailored in the late 19th century differ from the above Polyaki shirts of their appearance: design, color, and location of the decorative patterns.

The upper part of shirt No. 6861-15 consists of two pieces of bleached linen; the lower part is made of three unbleached pieces 46–47 cm wide (Fig. 17). The hemmed edges are attached together with small diagonal “over the edge” stitches, like in Polyaki shirts (see Fig. 1, b , d ). The sleeves are sewn of two straight pieces of fabric of unequal lengths in the manner different from that of Polyaki women’s shirts, in which the corners of the long piece are folded in kul . Vetka women from the southern regions of Krasnoyark Territory positioned the long piece of fabric such that it started from the neckline, while the straight sleeve was shirred at the wrist. Such features as shirring at the sleeve-bottoms, stand-up collar, and type of decoration pattern make this clothing very similar to

Fig. 16. Connection of a sleeve with a body-part and a gusset. Shirt of the middle 19th century. Novosibirsk State Museum of Local History and Nature, No. 9718.

Fig. 17. Gomel migrant women’s non- polik shirt. The village of Irbey, Irbeysky District, Krasnoyarsk Territory. KMLH, No. 6861-15.

the shirts of Gomel residents (Lobachevskaya, Zimina, 2013: 259). In the middle of the 20th century, the village of Neglyubka, Vetkovsky District, Gomel Region, was the only place in Belarus where such shirts (including polik ones) were still in use together with the open-fronted clothing, poneva skirt (Ibid.: 22).

The techniques of hand-sewing the Irbey (and Neglyubka) and Polyaki shirts are simple and efficient. The straight fabric-pieces are attached butt-to-butt, the hemmed edges of the upper ( stanushka ) and lower ( podstava ) parts are joined together with diagonal “over the edge” stitches. The Irbey and Neglyubka shirts, like the Polyaki ones, show collars and plackets executed with felled seams using red linen threads (Fig. 18). The same seam is used in sewing together the details of sleeves additionally decorated with the woven strip of red linen threads (Fig. 19). The pattern, in the form of geometric figures (rhomboids and squares with extended sides) decorating the shoulders, at the joints with the body-part of the shirt, is close to the original Neglyubka patterns but not identical to them (Ibid.: 265). The bottom hems of the Irbey shirts are decorated with woven bands of checker pattern made of red (6851-15) and white (685117) linen threads.

Shirts of migrants from the Chernigov region of the first quarter of the 20th century

During the field studies of the 1980s–1990s, we have recorded abundant women’s linen shirts of the Ukraine migrants. Archives of Siberian museums and private collections contain mainly shirts with the body-parts made of one cloth (dodilna shirt), which makes them distinct from the shirts of the Russian and partly Belarusian Old-Believers. K. Moszynski (1967: 446–448) considered this type of clothing to be unrelated to the common two-part shirt, and made an assumption about the origin of the one-cloth shirts from the archaic overcoat (poncho). As is known, in the Middle Dnieper region, such shirts were worn together with homemade closed- and open-fronted clothing (andarak and plakhta skirts), which quickly fell out of use in Siberia (like Gomel poneva skirt) and survived only in some museum collections.

Migrants from the northern regions of Chernigov, adjacent to Vetka settlement, brought to Siberia the tradition of stitching the polik inserts of shirts along the weft. Subsequently, this tradition became very popular in tailoring the clothes of Siberian women of Ukrainian origin. One shirt, belonging to the descendant of Chernigov migrants, D.E. Lakizo*, shows a pattern on the shoulders, in the form of a “floral vine”, embroidered with linen threads dyed red and black, and the same pattern is executed at the bottom hem, on the loose fabric (Fig. 20). The body-part of the shirt is sewn of three cloths 45 cm wide, and the sleeves are attached with diagonal “over the edge” stitches. Shoulder-inserts are attached to the sleeves and to the body-part with lap seams using back-stitches

)

Fig. 20. Connection of polik-insert, body-part with sleeve, and gusset. D.E. Lakizo’s polik shirt. The village of Penkovo, Maslyaninsky District, Novosibirsk Region. FMA, 1989.

Fig. 18. Shirt-collar. KMLH, No. 6861-15.

Fig. 19. Connection of sleeve-parts. KMLH, No. 6861-15.

and diagonal stitches. Gussets under the arms are sewn in the same way. In this shirt, as in Irbey shirts, a special seam (here, a faggot seam) is used to mark the joints of inserts with sleeves and back-pieces on the back (Fig. 20). The sleeves are made of linen pieces shirred at the wrist and fixed with cuffs. Unlike the Polyaki shirts, the shirt under consideration has the neckline gathered on one thread and fixed with a narrow stand-up collar. The collar is a strip 1 cm wide; it is attached to the shirred neckline with a lap seam, and from the wrong side it is hemmed by tiny, nearly invisible diagonal stitches with a felled seam (Fig. 21). Additional back-stitching enforces the collar shape. Along the collar edge, scallops are made by embroidery stitches. The collar is fastened with one metal button and a linen loop buttonhole. The cuffs, without any clasps, are attached in the same way.

Fig. 21. Collar. D.E. Lakizo’s polik shirt. The village of Penkovo, Maslyaninsky District, Novosibirsk Region. FMA, 1989.

Another shirt of Daria Lakizo’s is composed of three linen pieces of the body-part attached butt-to-butt, with sutselny sleeves*, shirred at the cuffs (Fig. 22). The cloths of the sleeves are cut step-wise; the protruding parts serve as gussets; and into the formed benches, pieces of the bodypart are inserted. This type of cutting of sutselny sleeves differs from that of the abovementioned shirts (where fabric-pieces of different lengths are used), but is identical to the style of the Polyaki burial shirts (see Fig. 2). Such shirts with one-piece sleeves, attached along the weft, were broadly used in the Middle Dnieper at the end of the 19th to early 20th century (Nikolaeva, 1988: 82–84).

In terms of tailoring technology, this shirt of Lakizo’s is substantially the same as that described above. It also shows the joints of back pieces with the sleeves marked with faggot seams, and edges of the collar and cuffs executed with embroidery stitches. The shoulders are decorated with a weaved zigzag line and embroidery executed with red and black linen threads in cross and half-cross stitch technique (Fig. 23). According to Lakizo, she weaved, sewed, and embroidered all these clothes herself in 1927–1928.

Conclusions: adherence to traditions

Analysis of the underwear shirt tailoring technology of the Old-Believers and non-Old-Believers who had migrated from the Dnieper-Desna interfluve allows some conclusions to be drawn. Apparently, the home-made ritual, burial, and wedding linen clothing of the Polyaki Old-Believers demonstrates the most ancient sewing techniques. This conservatism is explained not only by the predominance of manual labor, but also by the special attitude to clothing of the people who lived in the not-so-distant past. Historical materials provide evidence of the long persistence of many pre-Christian superstitions among the population of Russia, including the members of the royal family, up until the 17th century (Gromov, 1979: 205). The technology of tailoring the shirts under study reflects the old remnant ideas on the necessity to protect oneself from dangerous deceased who died unnaturally, and also to protect the body from evil forces, illnesses, and incantations. This was probably the reason for using the felled seam (loop-and-knot

Fig. 22. Construction of D.E. Lakizo’s shirt with one-piece sleeves. The village of Penkovo, Maslyaninsky District, Novosibirsk Region. FMA, 1989.

Fig. 23. Connection of sleeve with body-part. D.E. Lakizo’s polik shirt. The village of Penkovo, Maslyaninsky District, Novosibirsk Region. FMA, 1989.

stitch*), edging the collar and the sleeve bottoms with plaits, embroidery in the form of geometric pattern at the bottom hem, at the joint places of polik -inserts and sleeves with the body-part, and of sleeve-pieces with each other.

The process of polik shirt modeling, including non -polik shirts, required special technical skills. Types of seams and stitches were adapted to sewing straight pieces of fabric, where cloths were connected with minimal seam allowance (one or two threads) for the sake of fabric economy and aesthetics. The connecting seams (along with their main function) also served as symbolic and decorative elements.

In the clothes of the discussed groups of population of Altai, Krasnoyarsk, and the Novosibirsk region of the Ob, gored details in the sleeves of shirts made of store-bought fabrics began to be used considerably later than in the residents of the European part of Russia. This was accompanied by the spread of the so-called blind seams (lap seams with closed edges). For example, even in 1920s–1930s, in Siberia, there were no shirts with oblique sleeves, which were common in shirts of the population of Central Russia and its non-Slavic neighbors (Maslova, 1987: 268; Manninen, 1957: 107–111).

In the middle 19th to early 20th century, traditional shirts of Russian Polyaki Old-Believer women, as well as migrants from Gomel and Chernigov regions, were shirred at the neckline, and had wide sleeves made of straight fabric-pieces (such shirts, so-called Renaissance shirts, are known among European peoples) (Gaborjan, 1988: 31). However, in the ethnographic materials, no Polyaki women’s shirts with kul sleeves have been found that would be identical to such Renaissance shirts in terms of design and ornamentation. Analysis of the clothes kept in a number of capital and local museums, which sometimes don’t have the required documentation, allows a conclusion to be drawn about a single tailoring technology for men’s and women’s shirts, and hence, about the belonging of their owners to the single group of Russian Old-Believers known as Polyaki .

At the same time, the techniques of manufacturing women’s underwear in the studied Old-Believer and non-Old-Believer groups of Southern Siberia, which migrated from contiguous territories of Bryansk, Gomel, and Chernigov regions (Pogranichye), have shown many features in common. Moreover, all sewn clothes of these migrants demonstrate features typical of industrial production rather than of hand-made articles, which attests to the high tailoring skills of the artisans, and supports the assumption of some ethnologists on the common Slavic origin of polik shirts (Lebedeva, Maslova, 1967: 218). For instance, shirts of the Polyaki women and the Vetka migrants living in the Krasnoyarsk region demonstrate distinct design and sleeve construction, but show common tailoring features: butt joint of pieces of the body-part, hemming of the bottom with a felled seam, etc. Most indicative is the common method of connecting the upper and lower parts in polik and non-polik shirts (attachment of folded edges with diagonal stitches), which allowed repeated replacement of the lower part. This tailoring technology was less popular among the Ukrainian migrants; the bodies of their shirts were made mostly of one piece of fabric. The techniques of hemming the sleeve-bottoms (other than cuffs) in the shirts of Belarusian/Ukrainian migrants and of Polyaki women were different, owing to the difference in the sleeves’ design. Similar technology (connection of sleeveparts with knitted lace strips) was used by Semeyskie Old-Believer group in Trans-Baikal, which are related to Polyaki. However, Polyaki and Semeyskie underwear clothes do not show many common features, because the Trans-Baikal Old-Believers began comparatively early to use store-bought fabrics and to cut oblique sleeve details, which required special tailoring techniques. Polyaki women, while showing similarity to Belarusian/Ukrainian migrants in many sewing techniques and execution of collar through gathering, still differed from them and from their Altaian neighbors (Bukhtarma and most part of the Uimon Old-Believers), who shirred fabric at the collar with a vtachkyu stitch.

The analysis of the underwear of the population who migrated to Southern Siberia in the 18th–early 20th centuries from the Pogranichye region, where three branches of the Eastern Slavs met, intermixed, and separated (Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians), gives grounds for the interpretation of the further development of their culture and ethnographic transformations.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 14-50-00036).