Turkic inscriptions in Cyrillic on 14th-15th century eastern European Lithic artifacts

Автор: Medyntseva A.A., Koval V.Y., Badeev D.Y.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145452

IDR: 145145452 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.4.105-111

Текст обзорной статьи Turkic inscriptions in Cyrillic on 14th-15th century eastern European Lithic artifacts

Throughout their entire history, Slavic tribes and state associations coexisted in Eastern Europe with settled, semi-nomadic, and nomadic peoples, including the Iranian- and Turkic-speaking peoples. The Old Russian state had the closest trading and cultural ties with Volga Bulgaria—a multitribal (yet Turkic in its essence) state entity, which emerged in the Middle Volga region in the 10th century. Volga Bulgaria was not only a military rival of Russia, but also a permanent partner in craftsmanship and trade. Russians constantly lived on its territory, while Volga Bulgarian merchants and craftsmen also permanently lived in Russian towns (Poluboyarinova, 1993: 116–118). The relations of Rus with the Turkicspeaking peoples of the steppe zone of Eastern Europe

(the Khazars, Pechenegs, Torks (Guzes), and Cumans) in the 9th–13th centuries were just as diverse.

After the Mongols conquered a significant part of Eastern Europe, all Turkic-speaking peoples who had settled on this territory became a part of the Jochi Ulus (the Golden Horde). Its main spoken language was the Turkic language of the Kipchak type. The writing systems on the territory of both Volga Bulgaria and the steppe zone differed from the Old Russian system both in terms of language and alphabet (the Cyrillic script), which was adopted by the Russians from Bulgaria of the Balkans. Writing based on Arabic script spread in Volga Bulgaria with the adoption of Islam in the 10th century. Unfortunately, manuscripts of the pre-Mongol period from the territory of Volga Bulgaria have not survived. We can get some idea of the Volga Bulgarian language

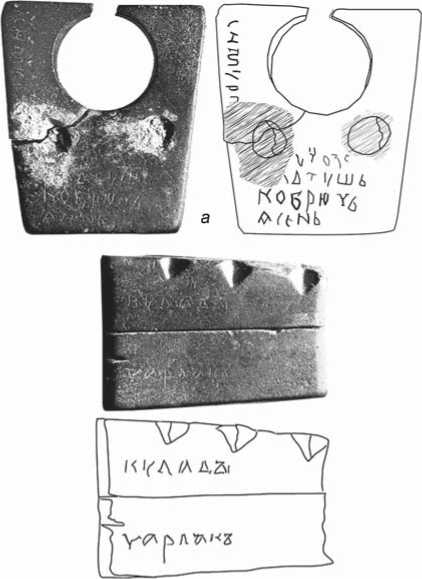

of this time from epigraphic monuments—epitaphs on stone gravestones, made either in Kufic writing in the Turkic language, or in Arabic. The surviving early epigraphic monuments of Volga Bulgaria go back to the 13th–14th centuries (Mukhametshin, Khakimzyanov, 1987; Khakimzyanov, 1987), but they do not fully reflect the living spoken language, which was used in everyday life by the population of this state. Therefore, a rare find of an inscription on a casting mold discovered at the Bolgar fortified settlement during the excavations conducted in 2016 by a joint team from the Institute of Archaeology of RAS and Institute of Archaeology of the Academy of Sciences of Tatarstan is of great interest (Medyntseva, Koval, Badeev, 2018) (Fig. 1).

Description of finds from Bolgar and Polotsk

The casting mold with an inscription was found in the very center of the Golden Horde town of Bolgar. It was a part of a large set of casting molds that belonged to a workshop for casting non-ferrous metal products,

b 0 1 cm

Fig. 1 . Photos and tracings of the casting mold from Bolgar with inscriptions. Stored in the Bolgar State Historical and Architectural Museum-Reserve. Photo by A.A. Medyntseva.

a – flat, segmented surface of one of the halves; b – trapezoidal end.

which had been completely destroyed by digging works. During archaeological studies conducted in 2016–2018 (excavation area CXCII), only a part of the household with the workshop was unearthed. A set of 86 intact and fragmented halves of casting molds was found during the excavation at the site (Badeev, Koval, 2018: 280– 283, fig. 6). The workshop probably functioned in the mid 14th century (1350–1360s); however, subsequently the molds became redeposited and ended up in pits, which were filled in the 1360–1380s. The paleographic features of the inscription correspond to the time indicated by the stratigraphic date (Medyntseva, Koval, Badeev, 2018: 144).

The casting molds were made of various materials, including local white stone (limestone, marl), schist rocks from the Urals, and fragments of Central Asian talchlorite pots*. Shield rings, bead temple rings, plate bracelets, a needle case, various pendants and medallions, mushroom-shaped weights, buttons, beads, belt plaques, and tops of headdresses were cast in them (Badeev, Koval, 2018: Fig. 6). As a rule, personal adornments did not have a specific ethnic association; however, all of them were typical primarily of the territory of the Golden Horde, although they also appeared at the sites of Medieval Rus as imported products. Many casting mold halves have graffiti in the form of circles, images of birds, lines, zigzags, grids, or geometric figures (Fig. 2). Some halves constitute sets and precisely fit each other, including two halves for casting a shield ring, on which barely visible inscriptions have survived. Both halves were carved from dense black schist with fine scintillating inclusions. The inscriptions were drawn very shallowly, and consisted of small letters, making it difficult to read and photograph them. They were made on the trapezoidal ends of both halves and on the flat side of one of them. Unfortunately, two through holes for connecting pins made of lead were made next to the inscriptions. As a result of lead corrosion, two lines of the inscription were hidden by adhering lead oxides. The inscriptions were made in the Cyrillic script, as evidenced by specific Cyrillic letters x, |, z, “, R, but the language of the inscription was not Old Russian. Most likely, the Cyrillic letters rendered the inscription written in one of the Turkic dialects. Before the conquest by the Mongols and at a later time, the main population of Bolgar consisted of Turkic-speaking Bulgars, and was constantly enriched by an influx of Turkic-speaking peoples from the vast territories of the Golden Horde, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. The Turkic language of the Kipchak type, as scholars believe, became the main language of the Golden Horde by the 14th century (Khalikov, 1989: 124, 129–131).

The letters on the side surfaces of the mold are best preserved. We can clearly read two words there (one on each half), which constitute one inscription: KykA(E)R )АРЛАКЪ ( kula(b)y/ charlak ). The first word has survived in the modern Tatar language in the form of kalyp and means “mold, form for casting molten metal” (Tatarsko-russkiy slovar, 1966: 218). It is also known from the modern Bulgarian language in the form of kalp with the meaning “form, sample, block” (Bernstein, 1975: 247).

Thus, if we take into account that the inscriptions were drawn on one half of the stone casting mold, they can be considered to be the signature of the stone cutting artisan who made

Fig. 2 . Graffiti on the casting molds from Bolgar. Photo by V.Y. Koval.

this mold (Medyntseva, Koval, Badeev, 2018: 142). Such signatures of artisans appear very rarely on Old Russian products. These are the well-known signatures on Maxim’s molds from his jewelry workshop, which was destroyed during the conquest of Kiev by the Mongols in 1240, and two signatures with the same name from the layers at the site of the scorched ruins of Serensk destroyed by the Mongols two years earlier (Medyntseva, 1978; 2000: 71–73). Judging by the possessive form of the name “Maxim” in the inscription, it was most likely inscribed not by a carver-artisan, but by a jeweler-caster who was marking his property. A graffito on a mold of the 13th century from Novgorod with the image of a warrior and the name Danila has been interpreted as a signature of the caster (Rybina, 1998: 37–38). The inscription on the molds from Bolgar was definitely left by the stone-cutting artisan and can be understood as “cut the mold” or “the mold of a cutter.” This reading gives us the key to deciphering a more extensive, but unfortunately damaged inscription on the front side of one of the halves of the mold (the word charlak was inscribed on its side).

Only indistinct characters have been preserved from the first two lines, which were damaged by oxides. The first line is completely illegible; four letters ТУШЬ ( tush’ ) are visible in the second line; the last three letters can be read quite clearly. These may be the remains of the word preserved in the modern Tatar language as tash- ‘lithic, made of stone’ (Tatarsko-russkiy slovar,

1966: 523), written in Cyrillic, with the character Ь at the end of the word. Notably, the Cyrillic letter “izhitsa” was used in the inscription to transmit a sound close to А (see the word kulaby above). The last two lines have been preserved much better, and the words ко(е)р~)ь “сень (ko(v)ryuch’ yasen’) can be read. The last word is quite clear: this is a Cuman (Kipchak) name, which has appeared many times in the written sources. The Cuman Khan Yasen-Osen-Asen is known from the Old Russian chronicles (Polnoye sobraniye…, 1962: 76, 97v). In Bulgaria on the Danube River, two brothers (Asen and Peter) led an uprising of the Cumans in the late 12th century and then founded the dynasty of the Asenovites (Zlatarsky, 1972: 430– 480). Therefore, such a name has been historically attested to and its reading is beyond doubt. The word kovryuch (possible reading kobryuch, which does not change its meaning) most likely means belonging to an ail (patriarchal family, clan, kurin), named after the founder of the clan. Such collectives were parts of larger ethnic entities, for example, the unions of the Chorni Klobuky, Berendei, Torkiis, Kovui, as well as the “tribes” of Moguts, Tatrans, Shelbirs, Revugs, and Olbers. The name of the large tribal association of the Koui (Kovui) has the greatest consonance with the word kovryuch. According to the Old Russian type of word formation, kovryuch should be the possessive form derived from the root of the personal name Kovryut or Kovryui with the possessive suffix -ich, which was used to designate both paternal names and ethnic (tribal) affiliation. Such a name is absent from Old Russian and Cumanian dictionaries of personal names, although it is quite possible that it existed in other Turkic languages. Thus, we can assume that the inscription speaks about the casting mold carved by a man named Yasen from the Kovryui clan.

Now we should turn to the beginning of the inscription—the line located perpendicular to the four other lines (first two of which were damaged by oxides, and the final two, which have been read above). At its beginning, the word qhlrp(c) ( simur(g) ) can be read*. This is the name of a mythical character widely known in the Iranian-speaking world. In Iranian mythology, Senmurv (Simurg) is a winged dog with two paws and claws, an intermediary between the celestial and terrestrial worlds, patron of crops and vegetation, which has two essences—benevolent and demonic (Trever, 1937). It is known that each Cumanian (and Torkic) tribal entity had its clan patron (totem) as an animal or bird. It can be assumed that the artisan indicated the name of the tribal totem at the beginning of the inscription, which was followed by his own tribal origin, occupation, and property—the casting mold that he made. The spread of Islam in Bolgar since the 10th century did not exclude the persistence of pagan views among the diverse tribes of the Golden Horde and probably tribal totems (even in the 14th century), especially the clan name, which was passed down from generation to generation.

A different interpretation of this inscription is also possible. Along with the word semirgÜk (Semurg, the mythical bird), the Cumanian vocabulary included the word semÜrgÜk —the name of an ordinary singing bird (Drevnetyurkskiy slovar, 1969: 495). Keeping this in mind, we can assume that the word SIMUR(G) designated a simple singing bird. Such an interpretation seems more preferable, since there are two graffiti with images of birds on another half of a casting mold from the complex under consideration (Fig. 2, 1 , 2 ). If one assumes that several carvers belonging to the same family clan worked in the same workshop, a competent artisan, while marking his product, left a rather lengthy benevolent (?) inscription; a second illiterate artisan marked the mold with images of the bird-totem, and other artisans made ornamental decoration or drawings. Signs resembling Turkic runes were made at the end of one of the molds in a row resembling an inscription (Fig. 2, 4 ). Some epigraphic and numismatic finds make it possible to conclude that the runic script of the Kuban type was preserved among the artisans of

*Only the vertical line is visible in the last character.

Volga Bulgaria living under Islam, until the 12th or even 13th centuries (Kyzlasov, 2012: 232). In our case, the runic-like characters only vaguely resemble the runic script*. A graffito in the form of a cross with flower-like ends on one of the molds (Fig. 2, 3 ) may be evidence that the casters of Bolgar were familiar with Christianity**.

In general, the inscription carries concentrated and at the same time multifaceted information about the occupation and origin of the mold cutter. In the context of the entire unique complex of casting molds, it can testify to close contacts between the Turkic-speaking population of Bolgar and literate Russian people, whose written culture was adopted by some of the local dwellers. At the same time, one cannot exclude the possibility that, along with writing, some basic concepts of Orthodox Christianity were also adopted.

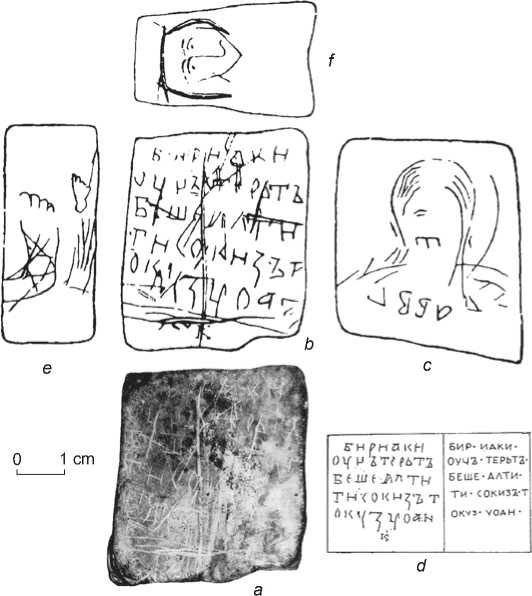

Another Cyrillic inscription in the Tatar language made on a flat stone tablet is known. It was found during the excavations in Polotsk over half a century ago. The inscription was published by G.V. Shtykhov (1963); it was deciphered and briefly commented on by B.A. Rybakov (1963). The item with the inscription was found in the layers of the 13th–16th centuries. A list of Tatar numerals from one to ten was drawn on the tablet in Cyrillic letters (Fig. 3, a , b , d ). According to paleographic features but without corresponding commentary, Rybakov dated the inscription to the 14th– 15th centuries and correlated it with the Tatars of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, who were settled there by Vytautas in 1397–1398. The language of the inscription was called Tatar, but taking into account the date of Rybakov, it is more likely that it was a dialect of the Tatar language called Tyurki. That dialect was spoken by the Turkic tribes resettled from the Urals-Volga region, who were invited by Vytautas in the late 14th–early 15th century for protecting the land against the German knights, and were later called the Lithuanian Tatars. However, it should be noted that according to some documents and legends, the Cumans from the Tugorkan clan who came to the Duchy of Lithuania, were already serving in Lithuania as early as the 13th century (Fedorov-Davydov, 1966: 228). Unfortunately, at the time of discovery, the tablet with inscriptions was in an unclear stratigraphic situation, mixed with the finds of the 13th–16th centuries, so it is impossible to clarify its date.

It is difficult to date the inscription discovered in Polotsk on paleographic grounds owing to its poor preservation. However, its closest parallel in terms of time and type is our inscription on the mold from Bolgar. Indeed, the letter И with a horizontal bar, equal sized loops in the letter В , triangular loops in the letters Ь and Ъ measuring half of the height of the letter, represent archaic features for the 13th–14th centuries in both inscriptions. Moreover, the letter ' has “rounded” loops, which in manuscripts serves as a sign of the second half to late 13th century. The letter Y in two cases resembles the shape of the number 4 with its long curved tail. Experts in birch-bark letters call this form “Ч-shaped”, and letters of this form are known from the group of birchbark manuscripts dated to the second half of the 14th to early 15th centuries (Zaliznyak, 2000: 189, pl. 21). In the third case, the letter Y has a shape like in the inscription from Bolgar (see the commentary above). Both inscriptions (from Bolgar and Polotsk) must have been chronologically close; therefore, Rybakov had some grounds for dating the inscription from Polotsk to the late 14th–15th centuries. Other features of the inscription from Polotsk, which were not mentioned by the publishers, include Ц ( tsi ) instead of ) ( cherv ) in the word uch ( three ) and the opposite designation of the diphthong YO ( uoan-un – ten ). The first feature may reflect the dialect ts–ch merger typical of the Old Russian northwestern dialects (Zaliznyak, 2008: 34); the second feature may reflect the transmission of sounds of the Early Tatar language with the help of Cyrillic letters. Turkologists will probably find an explanation for these dialectic features, which will make it possible to more accurately describe the specific nature of the Turkic dialect in both inscriptions, especially since Rybakov pointed to some regional parallels to the Tatar numerals.

The inscription from Polotsk is an important testimony to the regional Early Tatar language of a population that was in an isolated foreign language environment. Unfortunately, this inscription did not become the object of close attention for its first publishers. Neither the drawings on the back longitudinal side and end surfaces of the tablet, nor even Cyrillic letters representing the beginning of the Cyrillic alphabet caused much interest on the part of researchers. Only in 2011, in a comprehensive study of Belarusian epigraphy, I.L. Kalechits cited the Cyrillic transliteration of the inscription on the front (?) longitudinal surface, gave a description of drawings on the back longitudinal side, as well as the transverse

Fig. 3 . Inscription on the front longitudinal side of the item ( a , b ) and its reconstruction ( d ), tracing of images on the back longitudinal side ( c ) and ends ( e , f ). Photo of the item: (Shtykhov, 1963: 247), inscriptions on the front side: (Rybakov, 1963: 248).

sides, as well as her reading of the beginning of the Cyrillic alphabet on the back longitudinal side (2011: 58, 59, fig. 35). The transliteration of the inscription on the front longitudinal surface (in the works of Rybakov and Kalechits, Y0| was mistakenly transliterated as

Y)l ) is the following: БИРИЛКИ / ОГЦБТ6РБТ / Б6Ш6ЛЛТИ / THGOKHgzT окГзгоат / К .

On the back side, Kalechits read the inverted four first letters of the alphabetical sequence ЛББГ drawn under a chest-high image of a person with the remains of a halo around his head, reasonably considered by Kalechits as an attempt to reproduce an icon. For determining the date, Kalechits accepted the view of Rybakov, but expressed some doubts about his suggestion of considering the author of the inscription to be a native Tatar speaker. She admitted that the inscription, including the alphabet and numeration, could have been written down by a student who was practicing writing the alphabet and Tatar numerals by ear, not knowing the Tatar language. Kalechits agreed with G.V. Shtykhov, who rightly called the stone tablet “a notebook of a student”. Probably, doubts about the use of the Cyrillic alphabet by the Tatar population were caused by the lack of “everyday” monuments of that type. Now, with the discovery of synchronous inscriptions in the Turkic (the Volga Turks?) language in the Cyrillic script in Bolgar, both of these finds have lost their exclusivity.

The presence of the Tatar population in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania is not something new, and the use of the Cyrillic script in writing is not surprising, since the Old Russian language in its Western version, as well as the Cyrillic script, were used there not only in everyday life, but also in official documents and chronicles.

Discussion

Notably, both Cyrillic-Turkic inscriptions, which were found in areas separated by great distance from each other, are associated with Christianity: an image of the cross appears on one mold from Bolgar (see Fig. 2, 3) and a sketch of the figure of a saint and the initial four letters of the Cyrillic alphabet appear on the stone tablet from Polotsk. As Kalechits rightly observed, the initial letters of the alphabet, drawn on a stone tablet, are evidence of learning how to write. It is important to note that the process of writing letters of the alphabet in the understanding of a person of the Middle Ages contained a sacred meaning. This becomes understandable if we take into account the process of teaching how to read and write, which differed from the present-day learning process. The order of letters and their names, which survived until the 20th century and became the basis of the very word “azbuka” (alphabet): “Az, buki, vedi, glagol, dobro…”, etc, are known from the preserved “Alphabetic Prayers”—the acrostics in which the initial letters of lines constituted the phrases of the prayer text. Their authorship is attributed to Cyril (Constantine) and his disciples. It should be kept in mind that teaching how to read and write began precisely with the alphabet prayers, which were memorized by heart. Later, an unknown scholar proposed memorizing not the whole verses, but only the initial words which made up the names of the letters arranged in a certain order—azbukas (abecedaria, alphabets) to facilitate the learning process of writing. While studying the alphabet, the students memorized the full names of the letters and at the same time the first sounds of the words, which started the prayer phrases. Thus, the learning process was inextricably linked with the prayer text; learning how to read and write occurred simultaneously with memorizing the prayer. Therefore, the writing of abecedaria (alphabets) had not only educational and practical meaning, but also a sacred meaning: the writer pronounced not the sounds as is done in the present-day teaching process, but the first words of the alphabet prayer or the entire prayer. Consequently, the unknown owner of the tablet was supposed to pronounce the words of the alphabet prayer while writing the letters of the alphabet. The presence of Cyrillic letters in the Polotsk inscription is a proof that its Turkic-speaking author was a Christian and Orthodox.

Conclusions

The inscriptions published in this article belong to the period of turbulent ethnic changes and emergence of a new “Tatar” language based on the Cuman-Kipchak language. At the same period, the Russian population moved to the Golden Horde in large numbers. The spiritual culture of the Russians included the Cyrillic script and Christian religious beliefs. The Cyrillic Turkic inscriptions, which illustrate the vernacular language Tyurki from the time when new ethnic identities were emerging, is important evidence for linguistic Turkic Studies and for the studies of contacts between Russians and steppe dwellers in the area of spiritual culture. These inscriptions testify not only to the familiarity of the Turkic-speaking population of the Golden Horde with the Russian language and writing, and their use of this writing for their own professional needs, but also to the adoption of the spiritual foundation of the Cyrillic writing (Russian Christianity) by some representatives of that population.