Two rare finds from the Maikop-Novosvobodnaya sites in the Black Sea region

Автор: Korenevskiy S.N., Yudin A.I.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.48, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145489

IDR: 145145489 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2020.48.2.029-037

Текст обзорной статьи Two rare finds from the Maikop-Novosvobodnaya sites in the Black Sea region

Two unique finds from the 2018 excavations at the Pervomayskoye and Chekon settlements in the Krasnodar Territory are of great interest as cult symbols of the Maikop-Novosvobodnaya community (MNC) tribes, which, far from being alike in the source of their formation, reflect their different beliefs. As an excursion into the historiography of the MNC concept, note that this was introduced instead of the former term “Maikop culture”, in order to preserve the originality of sites included in this culture against a rapid accumulation of new materials, and to distinguish their typological features. For example, analysis of the entire ceramics of MNC allowed us to reveal the diagnostic types of ware, indicative of four typological variants of this community (Maikop or Galyugaevskaya-Sereginskoye, Psekups, Dolinsk, and Novosvobodnaya). Their common features are the absence of artificial mineral admixtures in pottery paste, reddish or yellowish, ochreous tones of burnished ware, elements of ornaments finding analogies at the Eastern Anatolian sites of Arslantepe Phase VI A, the customs of burying the deceased in a flexed position on one side, covering bodies with red paint, and often placing them on a pebble spread on the bottom of grave. Each of the distinguished variants can be considered a special culture in terms of its formation conditions, but detailed mechanisms of their development are unclear so far (Korenevskiy, 2004: 49–64).

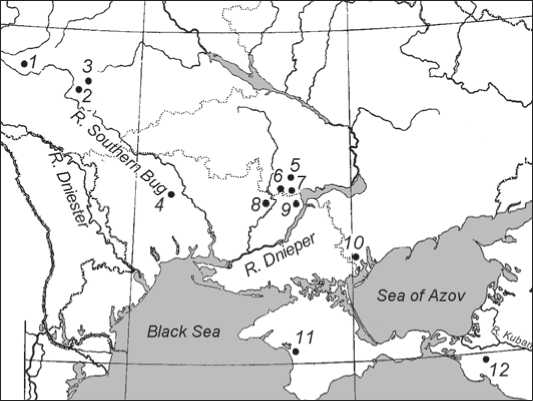

Fig. 1. Location of the Pervomayskoye ( 1 ) and Chekon ( 2 ) settlements.

The findfrom the Pervomayskoye settlement

The settlement is located on a terrace above the flood-plain of the right bank of the Psif (left tributary of the Kuban River). Its area is about 3.4 ha. The main territory of the settlement is built up with houses along Pervomayskaya Street in Keslerovo village, Krymsky District, Krasnodar Territory, which is 16 km southeast of Varenikovskaya village, and approximately 55 km northeast of the town of Anapa and the Black Sea coast (Fig. 1).

The total area covered by the archaeological studies at the Pervomayskoye settlement came to nearly 3000 m2. The cultural layer, covered by a plowing horizon, is a brown loam 0.4 to 0.6 m thick. 76 items, including three burials without grave goods, have been discovered during the excavations. Two buried people found at the lower level of the cultural layer were laid in flexed positions on their right sides. The third skeleton was in a round burial pit located above the utility pit’s mouth. The deceased was buried on his back, with his legs bent at the knees, his right arm extended along his body, and his left arm bent at the elbow.

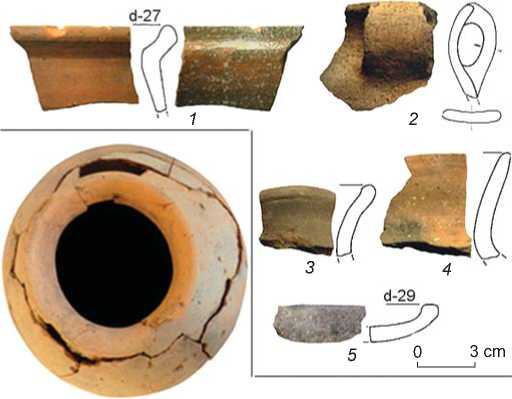

The archaeological materials obtained include MNC ceramics of two main types (Fig. 2); cone-shaped hearthattachments typical of the MNC Psekups variant; discs from the walls of vessels, with drilled holes; a clay model of wheel; a fragment of a clay ladle in the form of a small spoon; bone and stone items, including fragments of stone axes; and a bronze knife. The Maikop layer’s age can be determined according to the date obtained from the human bone found in burial 1: 4150 ± 70 BP (Ki-19677), 2979– 2892 BC, i.e. the 30th–29th centuries BC. It corresponds to the final stage of MNC.

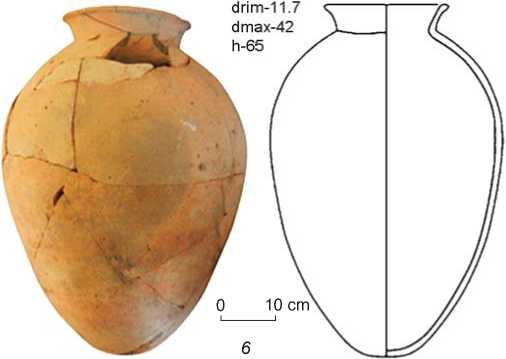

A pendant (Fig. 3) was found in the site area near the terrace’s edge, at a depth little more than 0.3 m from the surface, in the upper part of the cultural layer, at the same level as the Maikop ceramics (see Fig. 2, 1–4 ) and stone items (a flint flake, an axe fragment). The square where the pendant was discovered contained utility pits, but these were located 0.9 m below, in subsoil.

The item is probably made of horn. It has a yellowish color, a trapezoid shape, and an oval cross-section. The item’s surface is polished up. Obviously, it was rubbed

Fig. 2. Ceramics from the Pervomayskoye settlement.

0 3 cm

Fig. 3. Pendant from the Pervomayskoye settlement.

repeatedly in ancient times. The item is 30 mm long, 20 mm wide, and 7 mm thick; the diameter of the hanging-hole is 3 mm. A similar ornament is applied to the pendant on two sides: some kind of a sidelong cross at the center, and four surrounding cross-hatched triangles. The composition can also be represented as four joined triangles hatched using the parquet ornament.

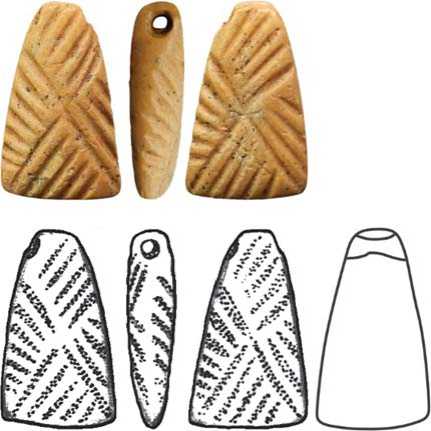

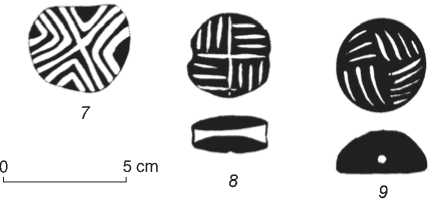

The pendant was probably an amulet. However, its ornament resembles those on Near Eastern geometric stamps, which allows the artifact to be attributed to this category of items. But, certainly, its function as a seal is conventional. Among the materials of MNC sites, two finds of this category are known. The first one is a jetty cylindrical bead from a burial of the MNC Psekups variant in a mound near Krasnogvardeyskoye village (Fig. 4, 1 ). There is a Tree of Life, with a deer standing in front of it, engraved on the bead. The bead is 1.9 cm long, its diameter is 1 cm (Nekhaev, 1986: 247, fig. 3). A.A. Nekhaev finds parallels among the Near Eastern button-seals. One of them originates from the Tepe-Gawra settlement, the other one (Fig. 4, 2 ) is obviously also from Mesopotamia (Ibid.: Fig. 3, 2, 4 ).

The second Maikop seal in the form of a cylindrical bead (3 cm long) has been found at the Chekon settlement

Fig. 4. Seals of the Psekups variant.

1 – cylindrical seal from burial 4, kurgan 1 of the Krasnogvardeyskoye cemetery (after (Nekhaev, 1986)); 2 – seal impression from Mesopotamia (after (Amiet, 1961)); 3 – cylindrical seal from the Chekon settlement (photo by S.N. Korenevskiy); 4 – development drawing of ornament thereon; 5 , 6 – seal impressions on the upper part, i.e. on the head of the cone-shaped hearth-attachment from the Natukhaevskoye-3 settlement (after (Shishlov, Kolpakova, Fedorenko, 2013)).

(Bochkovoy et al., 2013: 11) (Fig. 4, 3 ). Its surface is smooth, burnished, and dark. The bead is apparently made of a clay mass saturated with mineral admixtures. It shows an incised ornament, whose development drawing presents a row of adjoining rhombuses hatched using the parquet ornament. On top and bottom, they are limited by double horizontal lines (Fig. 4, 4 ). Thus, the version of the parquet ornament on the cylindrical seal from Chekon is the same as that on the pendant from Pervomayskoye.

Two impressions of the same Psekups-type seal have been discovered on a fragment of the head of a coneshaped hearth-attachment from the Natukhaevskoye-3 settlement near Novorossiysk (Fig. 4, 5 , 6 ) (Shishlov, Kolpakova, Fedorenko, 2013). A geometric ornament with zigzags, resembling elements of the parquet ornament, is discernible on them. What could this ornament type have meant for ancient people? Let us give our version.

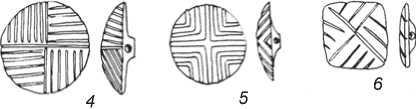

The parquet ornament on the button-seals is recorded in Mesopotamia since the Ubaid period (Amiet, 1961: Pl. 8, 154, 155). It is well traced on the finds from the Sialk III settlement in Iran (Fig. 5, 1–6 ) (Ghirshman, 1938: Fig. 8, 1 , 4 , 5 ; pl. LXXXVI, 117, 417, 1701). Seals with such an ornament have been discovered in layers XVI, XII, XI at Tepe-Gawra (Fig. 5, 7–9 ) (Tobler, 1950: Pl. CLIX, 21, 26, 27; CLXXII, 19, 24). At the same site, pendants with similar geometric designs have been

Fig. 5. Parquet ornament on the button-seals ( 1–9 ) and pendants ( 10 , 11 ).

1–6 – Sialk III (after (Ghirshman, 1938)); 7–11 – Tepe-Gawra, layer XVI, XII, XI (after (Tobler, 1950)).

found (Fig. 5, 10 , 11 ). The Sialk III antiquities generally pertain to the final Ubaid period and the Early-Middle Uruk epoch, with the overall range of ca 4500–3500 BC (Voigt, Dyson, 1984), like the above-mentioned Tepe-Gawra layers (Porada et al., 1984). The range of analogs for seals with the parquet ornament in the Near East can be wider, but currently we have enough information about such items that existed a little earlier than the MNC time, and about analogs from MNC period in Ciscaucasia in the 4th millennium BC.

Presumably, a stable use of such geometric ornament on the items could hardly have been a chance phenomenon. In terms of its function, the pendant-seal could have played the role of a property mark, or be understood as something whose ornament took on a magical meaning. Analysis of later Anatolian seals can be a help in clarifying the situation. Items from Izmir, from the Abu-Habba (Sippar) settlement, and accidental finds from the collections of Anatolian antiquities (Fig. 6) show representations of the fertility goddess, surrounded by various symbols and items, including round and square tokens with parquet ornament (seals?). Thus, the semantics of this ornament is directly related to the magic of a Great Goddess and her magical functions. The above items are dated to 2400–2200 BC (Tonussi, 2007: SM/4, SM/6, SM/8, SM/9). In all probability, this interpretation of the parquet ornament’s symbolism can be extended to more ancient beliefs of Near Eastern peoples, taking into account a deep conservatism inherent in the cults of the goddess—the patroness of every living thing.

Thus, pendants from Chekon (see Fig. 4, 3 ) and from the Pervomayskoye settlement (see Fig. 3) can be considered amulets with symbols of the fertility cult. Seal impressions on the head of the cone from Natukhaevskoye-3 were probably symbols of a goddess responsible for the flourishing of all living beings, on something associated with her cult (Korenevskiy, 2013). In terms of its significance, a cylindrical seal from the kurgan near the Krasnogvardeyskoye village (see Fig. 4, 1 ) also belongs to the artifacts with fertility cult symbolism, personified, in particular, by the Tree of Life depicted on the seal.

Seals as an economic phenomenon of the Near Eastern population were a conspicuous indicator of the development of ownership rights in pre-state formations relating to the beginning of the establishment of a production economy, such as, for instance, the finds from the Tell Magzaliya settlement, a site of the pre-Hassuna

Fig. 6. Impressions of Anatolian seals with representations of goddess and tokens with parquet ornament, 2400–2200 BC (after (Tonussi, 2007)).

1 – Izmir; 2 – Abu-Habba (Sippar); 3 , 4 – the exact place is unknown (Anatolia).

period of the 8th–9th millennia BC (Bader, 1989: 103, pl. 39, 2 ; p. 314). In the Caucasus, seals appeared in the Northern Mesopotamian cultures in the 4th millennium BC, known as the Leyla-Tepe culture of the Southern Caucasus (Museibli, 2007: 173, fig. 14, 1 ) and its close analog—MNC of Ciscaucasia. Did these pendants play the role of the property marks in the Caucasian population? The question is still open, since the number of such finds is very small. It is more justified to regard them as symbolic amulets, which were worn in the form of beads and pendants.

In the MNC materials, the parquet ornament is also encountered on bone “pins” from the Solomenka kurgan (Kruglov, Podgaetsky, 1941: 195, fig. 33, 7 ) and burial 9, kurgan 11 of the Klady cemetery (Rezepkin, 2012: 145, fig.16, 6 ). It is also represented on the Dolinsk-type ceramics; for example, from the Inozemtsevo kurgan studied in 1976 (Korenevskiy, 2004: 88, fig. 58, 1 ) and burial 13, kurgan 5 of Nezhin group II (Ibid.: 189, fig. 59, 6 , 7 ). Such decoration was recorded on the ridge vessel from burial 20, kurgan 11 of the Klady cemetery (Rezepkin, 2012: 151, fig. 23, 5 ) and on a Psekups-type vessel from a burial of the Ventsy kurgan in the TransKuban region (Korenevskiy, 2004: 186, fig. 56, 10 ). In general, it can be said that the parquet ornament became a rather widespread symbol of the fertility goddess among various tribes of the MNC at the late stage of its existence.

The find from the Chekon settlement

The settlement is located near the village of the same name in the Anapsky District, Krasnodar Territory, on the left bank of the Chekon River (right tributary of the Kapilyapsin River, the right bank of the Kuban River). Its total area exceeds 25,000 m2. Earlier, excavations at the site were conducted by V.V. Bochkovoy (2011) and A.D. Rezepkin (2014). They opened more than 1000 m2

of area (Bochkovoy et al., 2012; 2013: 5–16; Rezepkin, 2014). In 2018, more than 6400 m2 of cultural layer ca 1 m thick were studied (Yudin, Kochetkov, 2019). Here, saturation with various artifacts is greater than that at Pervomayskoye, but in general the materials are culturally comparable. This site also pertains to the MNC Psekups variant. Two dates have been obtained for it: from the animal bone found in the cultural layer of the settlement – 4480 ± 80 BP (Кi-19621), 3352–3120 BC; from the human bone found in burial 1 – 4380 ± 60 BP (Кi-19679), 3091–2911 BC, which corresponds to the late 4th to the early 3rd millennia BC.

During the 2018 excavations, dwellings, utility pits, cult structures (?), and burials were discovered at the Chekon settlement. No traces of hearths have been revealed, though accumulations of adobe and lumps of calcined clay are common in the cultural layer. Deep pits expanding towards the bottom and filled with adobe bricks, ceramics, and stones are, presumably, the remains of cult structures. On their bottoms, ash and several pieces of charcoal are recorded; however, no traces of red calcination caused by long-term use of hearths have been found. Nine burials have been studied, among which four are paired, and one is triple. There is no unified burial rite.

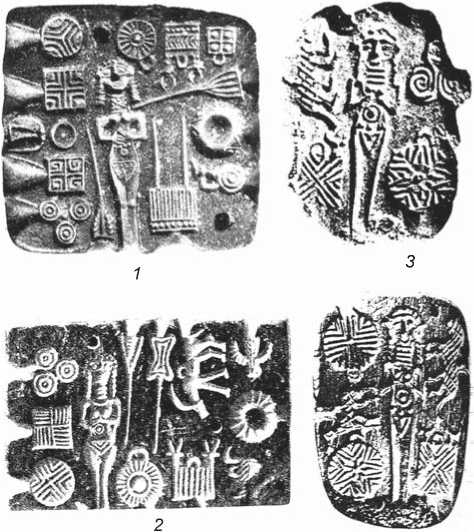

The bulk of the finds is composed of bone animals and pottery. The latter includes two classes. The first is ware with strict symmetrical shapes, without mineral admixtures in paste. The reconstructed types are typical of the MNC Psekups variant (Fig. 7, 1–3 , 8 , 9 ). There are round-bottomed vessels of various size. Small fluted-body vessels are encountered. There are a lot of round-bottomed bowls. Vessels with an undulating line incised along the rim are encountered. The second class consists of molded ware with mineral admixtures in paste. Ceramic fragments with admixture of shells are observed.

Other ceramic items are hearth stands with hollow bodies (Fig. 7, 5–7 ), spindle whorls or wheel models (Fig. 7, 4 ), lids, and corks for vessels. Items made of copper-

Fig. 7. Ceramics from the Chekon settlement.

based alloys (20 spec.) have been found: small daggerknives, awls, pins, rods, a socketed axe, and production waste. Numerous stone items occur: large flint inserts, including those with serrated retouch, bored axes, hoes, pestles, burnishers, grinders, hammerstones, and abraders. Among stone items, borers, pipe-shaped beads, spindle whorls, a pickaxe, and a stemmed arrowhead occur (Yudin, Kochetkov, 2019; Yudin, Korenevskiy, Barinov, in press).

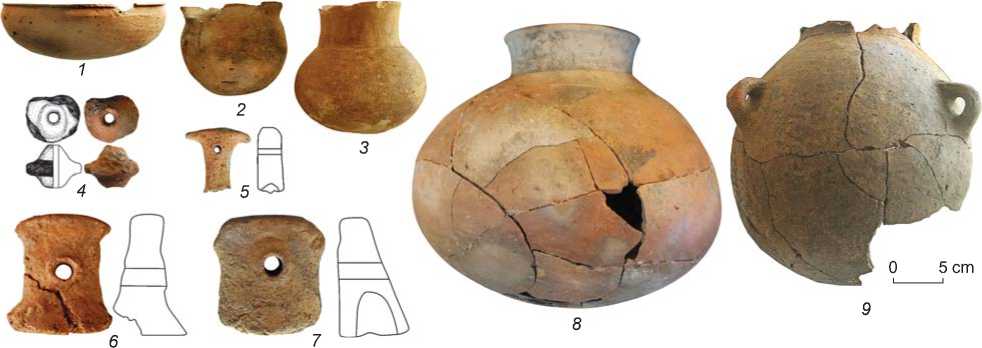

The clay anthropomorphic figurine under consideration, which can be interpreted as a statuette, has been found in the filling of a building located in the central part of the settlement. The contour of the structure resembles a rectangle with strongly rounded corners. The long axis of the building is oriented along the SE-NW line. The premises are ca 4.4 × 3.4 m. The pit’s bottom is uneven and sloping. It is seemingly divided into two parts with different directions of surface slope. It was possible to trace the walls to a depth of 14 to 50 cm. At the center of the building, there is a small pit about 1 m in diameter and max. about 20 cm deep from floor level. This structure is most probably the lower part of a half-dugout dwelling, while the upper one was above the native soil level and could not be clearly determined in the cultural layer.

Similar half-dugouts at Chekon are known from the excavations conducted by V.V. Bochkovoy (2013). The

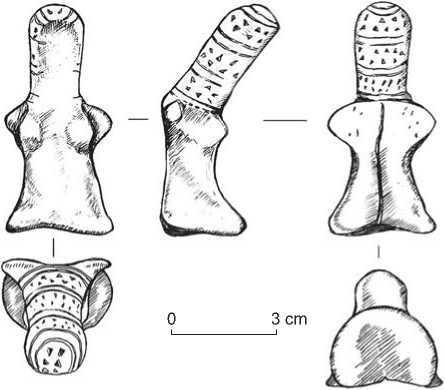

Fig. 8. Ceramic statuette from the Chekon settlement.

first publication about them has already been presented by E.N. Bulakh (2014). The typology of half-dugouts at the Black Sea region settlements of the MNC is under development currently. It can only be noted that they can be rounded or subrectangular. Such a subrectangular halfdugout is known at the Tuzla-15 settlement, located on the Taman Peninsula, in the Temryuksky District, Krasnodar Territory. The spot of the structure was recorded below the plowing layer, 25–30 cm above the native soil level. The excavations have demonstrated that the building had dimensions of 3.4 × 3.2 m and was oriented according to cardinal points. At the pit’s bottom, there was a depression. It was possible to trace the structure’s walls to a depth of 40 cm in the native soil (Korenevskiy, 2014).

A set of finds from the building where the statuette was found is typical of the assemblages from halfdugout dwellings of the MNC Psekups variant. Pottery breakage is observed therein. As a rule, intact items are not encountered. Fragments of the so-called wheel-thrown vessels, made using rotating devices, are present. Such ceramics do not contain mineral admixtures. Sherds of molded vessels with mineral admixtures also occur (Korenevskiy, 2004: 173, fig. 43, 77 , 81 ). Fragments of clay cone-shaped hearth-attachments are regularly found in such sets. Such domestic waste probably appeared as a result of filling the abandoned structure with fragments of ware and cone-shaped attachments as a special ritual finishing the use of the structure. What could this ritual have been associated with? Possibly, with the idea of revival and worshiping the fertility goddess, whose cult attributes in the MNC population were the attachments to hearths (Korenevskiy, 2013).

The clay statuette was in the northern corner of the building, almost on the bottom of the half-dugout. It is hard to say for certain whether it was left by the inhabitants of the structure or thrown into the dwelling to be abandoned. However, this item could have had the same symbolism as the hearth-attachments associated with the mother-goddess and revival cults. Therefore, discovery of a magic item relating to the great fertility goddess in the abandoned Maikop building is possibly not coincidental.

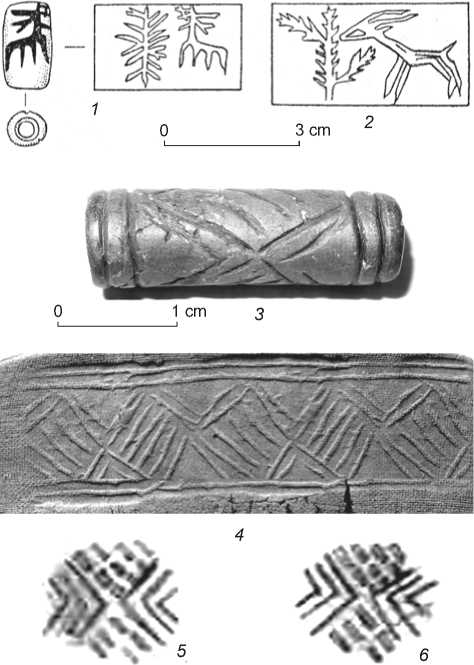

The anthropomorphic figurine has a slightly concave base, which ensures it can be placed in an upright position (Fig. 8). The height of the statuette is only 66 mm. The human figure is rendered schematically. The head and neck are well marked. This part of the figurine is slightly inclined forward. Its front surface is flat, without any images or details, while the back and side surfaces and the top of the head are covered with ornament. Possibly, such a manner renders a headdress resembling a scarf or a cape. The ornament includes horizontal strips, with two rows of pricks, divided by double lines.

In the upper part of the figurine’s body, there are two projections that could designate arms. The female breast

0 2 cm 0 2 cm

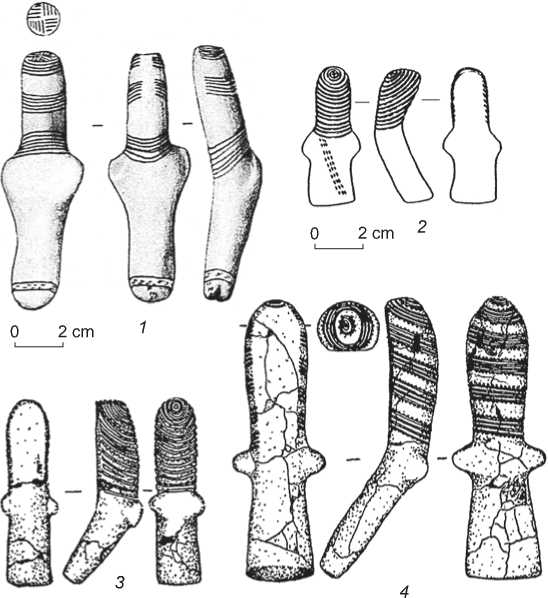

Fig. 9. Serezlievka-type statuettes (after (Burdo, 2018)).

1 – Sandraki; 2 – Shirokoye; 3 , 4 – Zeleny Gai.

is rendered by two convexities. This suggests that it is a representation of a female goddess. The lower front part of the figurine looks like a long garment (?). The rear side of

at the MNC sites. Figurines of sitting goddesses of the Southern Caucasus or Ciscaucasia pertain to the earlier time and the cultural context of the Southern

the torso is bisected by a vertical bar. It is not quite clear what this means. The bend of the torso most probably corresponds to the sitting posture, which is typical of many Chalcolithic anthropomorphic figurines of the Caucasus and those belonging to the Tripolye culture (Kovaleva, 2004: 498).

The closest analogs to the anthropomorphic figurine are among the Serezlievka-type statuettes (Fig. 9), including those from burial 26, kurgan 6 near the Zeleny Gai village, Dnepropetrovsk Region (Kovaleva, 2003: Fig. 3). I.F. Kovaleva points out that such statuettes occur in the rightbank steppe area of the Dnieper River, in kurgan burials, as attributes of the local Dnieper-Bug group of the post-Mariupol culture. In the burials of this group, the deceased were laid in a flexed position on their left or right sides, sometimes on the back (Videyko, 2004: 475). Sites of Serezlievka,

Sofievka, Usatovo, Gordineshty, and Gorodsk types pertain to the Tripolye CII phase, dated back to 3200–2750 BC (Videyko, 2003: 115). The dates obtained for the Chekon settlement in 2018 are in good agreement with this period.

The issue of cultural contacts between the Tripolye population and the Northern Caucasian tribes was raised earlier, also in connection with the Late Maikop sites (Zbenovich, 1974: 144–149). But in this case, the Serezlievka-type statuette found at a MNC settlement is a unique and incontestable example of such contacts. Notably, this is nearly the only evidence of ideological influence by the steppe people on the Maikop population.

N.B. Burdo has compiled a map of the distribution of Serezlievka-type statuettes (2018). Their area of distribution is associated with the Southern Bug and the right bank of the Dnieper River. One such statuette was found in kurgan 17 of the Zaozernoye burial ground, near Yevpatoria, in the southwestern Crimean Peninsula, though outside of burials (Popova, 2016). This find reflects the spread of the Tripolye (“Serezlievka”) goddess cult from the Late Tripolye tribes’ habitation area to the south. The discovery of a statuette of such a type at Chekon points to the penetration of this tradition even into the environment of tribes belonging to the MNC Psekups variant (Fig. 10). In this environment, the statuette of the Tripolye goddess looked like an unusual object of worship, since it is well known that there are no other clay statuettes of female goddesses

Fig. 10. Distribution of Serezlievka-type statuettes (after (Burdo, 2018), with addition of Chekon).

1 – Sandraki; 2 – Serezlievka; 3 – Dolinka; 4 – Petropavlovka; 5 – Zeleny Gai;

6 – Shirokoye; 7 – Ordzhonikidze; 8 – Baratovka; 9 – Chkalovo Group; 10 – Novoalekseevka; 11 – Zaozernoye; 12 – Chekon.

Caucasian Chalcolithic; for example, a statuette from the Galgalartepesi settlement in Azerbaijan (Narimanov, 1987: 224, fig. 28).

Thus, the discovery of the Serezlievka-type statuette at a settlement of the MNC Psekups variant testifies to obvious ties between the local population and territorially remote tribes belonging to the Dnieper-Bug group of the post-Mariupol culture, which possibly had their mediators in the Crimea. Moreover, the fact of finding such a cult figurine suggests that it was necessary exactly to people who adhered to the beliefs of a population influenced by the Late Tripolye culture rather than by the cults of the Maikop tribes. However, we did not manage to reveal ceramics of any other culture in the Chekon pottery assemblage. Is it possible, on the basis of this find, to speak about the presence of people of a different, “Tripolye world” at a settlement of the MNC Psekups variant? This question is worthwhile; however, it is hard to solve.

Conclusions

Let us sum up the results of our publication. Both the described items belong to the so-called markers of cultural relations. The pendant with the parquet ornament reflects the penetration of the symbolism of the Tree-of-Life cult and its associated mythology of revival and fertility from the south. Such a conclusion is in good agreement with the known concept, according to which formation of MNC in Ciscaucasia was conditioned by the migration of population from Northern Mesopotamia and the Southern Caucasus.

At the same time, it is more important to find an answer to the question why seals and a parquet ornament occur at the sites of the Psekups and Dolinsk variants and of the Late Novosvobodnaya group of the Klady cemetery, but not of the MNC Early Maikop variant, whose establishment pertains to the first half of the 4th millennium BC (3900/3800 to 3600 BC) (Korenevskiy, 2011: 27–30). It is poorly provided with sources so far; besides, such southern influences could have taken place in the Uruk time and in the Jemdet Nasr epoch, i.e. in the late 4th to early 3rd millennia BC (Vignola et al., 2019). Finding a statuette of the Serezlievka-type at Chekon points directly to absolutely different contacts between the local population and the Southwestern Black Sea region tribes—representatives of the Late Tripolye culture. These contacts were caused by some events of the MNC final stage that influenced the nature of the local cultural process.