Types of winter clothing worn by descendants of the Russian pioneers in Siberia (late 19th to early 20th centuries)

Автор: Fursova E.F.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnography

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145409

IDR: 145145409 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.1.137-146

Текст статьи Types of winter clothing worn by descendants of the Russian pioneers in Siberia (late 19th to early 20th centuries)

Until now, ethnographers have not given due attention to winter clothing, which had a special role in the life support system and traditional culture of the Siberians, mostly focusing on the description of types and varieties of clothing, and on identifying their names. A historiographic overview shows that scholars have not posed the question concerning climatic features of the winter clothing worn by the old residents of Siberia. In the process of research, the current author followed a multidisciplinary method, which made it possible to take a fresh look at this cultural phenomenon and its structural links (Tishkov, 2016: 5). This study analyzes only traditional homemade clothing, which was intended for protecting people from the snow and cold during everyday household work, as well as fishing and hunting activities. The author took into account the data on climate periods and temperature anomalies, which were noticeably manifested in Siberia (Kislov, 2001: 248, 255, 259). According to the studies of climate, prior to the 20th century the climate was much colder than today. Cold winters in Central Russia occurred in the 17th–19th centuries—the time of the Russian settlement in Siberia (Ibid.: 248).

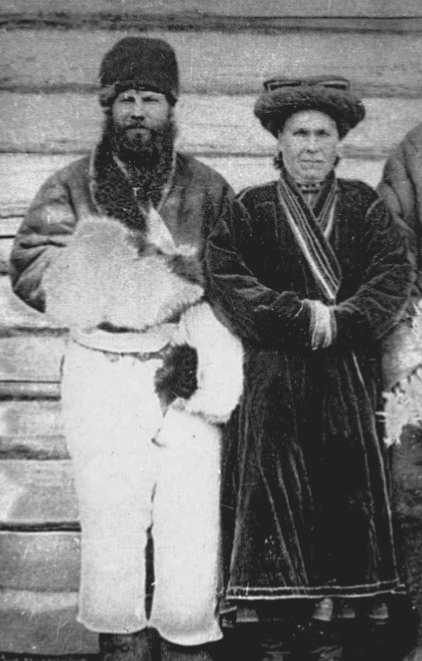

A Siberian dweller wearing a winter outfit looked large and clumsy, as is testified by sketches made by travelers and collectors of the 19th century (Fig. 1), now kept in archives, as well as recollections of contemporaries. The

Fig. 1. A Siberian wearing a winter outfit (Puteshestviya po Sibiri…, 1865: 254).

image of a Siberian (“Siberian bear”) was formed under the influence of the set of spacious fur clothing for the winter. According to numerous archival descriptions, the winter outfit of the inhabitants of Siberia was similar to the clothing set worn by the peasants of the Perm Governorate, which constituted the core of Siberian settlers (Na putyakh…, 1989: 10–16, 309; Sibir…, 2014: 99).

This study employed the manuscript by V.K. Multinov, “Clothing of the Angara People”, from the Department of Manuscripts of the Russian Museum of Ethnography (DM RME), which was virtually unknown to ethnographers. This manuscript describes the clothes of the local Chaldons* as “clothing of hunters and plowmen” (1926). The peasants in the south of that region lived in the taiga zone; accordingly, their non-agricultural activities were associated with forest-based gathering and woodworking, as well as hunting, and fishing. For identifying the common and particular features in the culture of the Siberians against a broad ethnographic background, the study used Western Siberian evidence obtained in field studies in the 1970s and 1980s, and related to the Russian old residents in various regions of Western

*Chaldons are the self-name of the Siberian old residents who associated their origins with the Don River and Yermak, the “conqueror of Siberia” (Fursova, 2015: 12–13).

Siberia, including the Uymon Old Believers of the Altai (Shitova, 2013: 74–75). The data from the studies of exhibits from museums in Moscow and regional capital cities, descriptions made by collectors (RME, Museum of History and Culture of the Peoples of Siberia and the Far East of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the SB RAS (MHCPSFE IAET SB RAS)), as well as archival materials (Russian Geographical Society (RGO), DM RME) have also been used.

Winter and hunting clothing of the Siberian peasants according to archival, museum, and field evidence

Multinov indicated the following varieties of men’s “lopot” (as winter clothing was called in the Angara region): azyam , zipun, or adneryadka *, shabur ( shoidennik ), fur coat, tulup , khalat, and coat (local name kozlovka ). “The ozyam or zipun”, as Multinov wrote, “is a type of armyak coat made of homespun woolen cloth, white or black, without a collar, rather wide; when put on, it is thoroughly wrapped (without fasteners) and tightly girdled with a belt or homespun long ‘sash’. When it is not particularly cold, the zipun is worn in villages in order to pass from one house to the other, and both men and women like to wear it with one sleeve (over one shoulder – E.F. ). A town coat is worn only by non-locals. <…> Of course, at work, especially while working in the forest, the zipun soon wears out and then it is covered with canvas. Such a zipun sewn over with canvas is called a ‘shabur’ or ‘shoidennik’. Rarely, a simple armyak made of canvas, which is worn instead of a zipun, is called a ‘shabur’” (1926: Fol. 17). Multinov pointed out that in some villages of the Angara region, “a shabur worn by women is called a ‘ponitok’** from the name of the fabric” (Ibid.: Fol. 21).

According to field materials, clothes such as the shabur and ponitok , which were worn by all sex and age groups (men, women, children), also belonged to everyday, working clothing in southwestern Siberia. Laughing at the stereotypical opinion of them as people who could endure cold especially well, the Chaldons would say, “What, can the parya***, really be cold—he took two shaburs from off the stove and both are hot!” The old residents explained this custom of dressing

“carelessly” in the winter by their careful attitude toward fur clothing and thriftiness, “What will happen to the parya; he put on two shaburs from the stove—both are hot! …It would be a pity to wear a fur coat”.

The description of the Altai zipuns collected for the funds of RME by the “statistician” S.P. Shvetsov in 1905 in the village of Uymon in Biysky Uyezd of the Tomsk Governorate, as stated in the inventory (RME, inventories of exhibits No. 1343-1, 1343-2, and 1343-3), was performed uniformly. It was only indicated that “the fit is like that of the Caucasian sleeveless burka cloak, but with sleeves. The sides are with gores, as are the sleeves”. According to the author’s inventory, zipuns were worn by both men and women.

In 1978, the Altai ethnographic team of the Institute of History, Philology, and Philosophy of the Siberian Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences (today—IAET SB RAS) recorded a zipun of homemade woolen brown fabric, belonging to A.F. Kharlamova in the village of Bystrukha, in the East Kazakhstan Region of the Kazakh SSR. The zipun of a tunic-like cut was sewn from two sheets 2.16 m long, folded over the shoulders. The sides were widened by gores, two on each side. The sleeves were slanted with one gore each; the armholes were straight. The edges of the sleeves were trimmed with black satin. The shawl collar was trimmed with homespun black linen. The zipun was hand-sewn in the 1920s using black and white coarse threads (FMA, 1978).

It was unthinkable to live without a fur coat in Western or Eastern Siberia. As described by Multinov, the fur coat was an ordinary sheepskin coat, yellow or dyed black, with a sheepskin collar. “There are no cloth-covered fur coats. Fur coats are sewn by village fur-coat specialists” (Multinov, 1926: Fol. 16). Such fur coats, as Multinov indicated, were worn daily not only by men, but also by women.

The Western Siberian version of this clothing was a festive fur coat made of sheepskin of light brown color, found in the village of Maloubinka of the East Kazakhstan Region of Kazakhstan—the territory where Russian Old-Believers, known as Polyaki settled. This fur coat was made in the early twentieth century. Local fur clothes of the Polyaki, according to the materials of the abovementioned expedition, did not differ from that of other groups of the old resident population. “This sheepskin fur coat is sewn with the fur on the inside; the shawl collar is trimmed with black karakul. Fur strips also trim the edges of the sleeves and bottom hem. The coat is of a straight silhouette, overlapping from right to left. The sleeves are made with a single seam; the armholes are straight” (FMA, 1978). Everyday fur coats were sewn from cheaper materials. Thus, the inhabitants of the village of Bystrukha in the East Kazakhstan Region preserved an old, home-sewn, short fur coat of black calfskin. “The wide collar is made of red calfskin. There are a straight silhouette and straight fastenings buttoned right to left. The sleeves are straight and wide. The fur coat was sewn with a lining of cotton fabric” (FMA, 1978).

Multinov noted that women’s festive clothing differed from men’s festive clothing in the Angara region, “This is a long coat padded with flax tow or even cotton, and on the outside covered with satin or another shiny fabric, sometimes with woolen cloth, with a fur collar and fur cuffs. Such a coat is a source of pride for its owner, and it is worn only on extremely solemn occasions: people wear it while going to a wedding, on a big feast day, or going to the parish church (for taking Communion). Such a coat is often made of costly fur (squirrel, sable)” (Multinov, 1926: Fol. 20). Types of outer clothes similar in appearance and design were worn by the female “Semeyskie” Old Believers of the Trans-Baikal region. The collection of the MHCPSFE IAET SB RAS contains a fur coat sewn from goat skins with the fur on the inside (No. 350, Buryatia, 1973, collected by T.N. Apsit). On the outside, it was covered with burgundy semi-silk fabric, probably kanfa dense satin (made in China) (Fig. 2). The sleeves were narrow, exceeding the length of one’s arms (80 cm). At the bottom, they were trimmed with black goat fur and two strips of braid. The collar and the edges of the flaps were also trimmed with fur.

In its design, the fabric covering was similar to Russian gored sarafans with two rectangular gores on the sides. In

Fig. 2 . Fur coat sewn from goat skins with the fur on the inside. MHCPSFE IAET SB RAS, No. 350.

an expanded form, the fur coat almost formed a circle. The silk fabric was sewn manually through the fur to the center of the back with small seams made with a forestitch. Stitching was made parallel to the connecting seam on the back on both sides of it. The stitches connecting the top and fur of the coat were also made in front parallel to the slit-fastener. Stitching with coarse linen thread was also made along the bottom of the hem. Apparently, later, with the spread of sewing machines, machine stitching was made over the hand-made stitches.

In appearance, such a fur coat resembled old-Russian unbuttoned fur coats of the 17th century with long sleeves, which were sewn from expensive patterned fabrics and were decorated with gold and silver embroidery (Gromov, 1979: 208). In contrast to medieval fur coats, the Semeyskie fur coats were khalat-like, without fasteners (overlapping to the left). In the middle of the 19th century, similar fur coats must have become known in Western Siberia, where non-covered fur clothes were valued less, while clothing covered with industrial fabric was considered expensive and prestigious. M. Serebrennikov thus wrote about the clothes of peasants from the village of Kamyshevo*, “In wintertime, men wear a sheepskin coat and zipun of homemade woolen cloth; on feast days, rich people wear fur coats made of the same sheepskin covered with blue or black industrial woolen cloth (my italics – E.F. ), while poor people use the same clothes as on ordinary days” (1848: Fol. 1). Women, as the author noted, “in the winter wear sheepskin coats and zipuns for work, and on feast days sheepskin coats covered with nankin or woolen cloth or drap-de-dames (my italics – E.F. ) with squirrel fur collars…” (Ibid.: Fol. 2).

Another fur coat of the Semeyskie from the TransBaikal region, kept in the same museum (No. 357, collected by T.N. Apsit), was sewn of sheepskin, and was covered with Chinese kanfa dense satin. The burgundy semi-silk kanfa of large-knit weave was decorated with knotted ornamental decoration, swastika images, etc. The fur coat was sewn with the fur on the inside, trimmed with strips of black hare fur on the bottom of the sleeves, around the collar, and along the flaps in front. Its length is shorter than the above-described fur coat No. 350. Examination of this fur coat, like the previous one, suggests that the craftsmen tried to remove all structural seams (including shoulder and side seams) of the upper fabric (kanfa) to the back. The elbow seams of the sleeves, when the fur coat is worn, are visible only from the back. Location of seams in the front could have been considered impractical or did not meet the aesthetic requirements of traditional clothing. The design drawing of fur coat No. 357, just as fur coat No. 350, corresponds to the design of gored sarafans supplemented with long sleeves (below the hands). The seams between the skins on the sides coincide with side seams of the upper fabric and are interconnected. The seams of the upper and lower parts of the fur are also connected along the center of the back; the rest of the seams do not match. The stitching (made by hand) runs in three vertical lines on both sides of the center of the back and in two vertical lines on the flaps. In this fur coat, just as in the fur coat described above, pieces of fur were sewn together and sewn to the fabric with slanting stitches using coarse linen thread.

The Trans-Baikal women wore festive fur coats over the shoulders, without a belt, as opposed to working khalat-like clothing. It is surprising that even in this clothing they managed to hold their children in their arms under the flaps. Prikhvatkas (ties woven of ropes to hold the flaps) were sewn under the flaps of fur coats at the waist level on both sides (No. 357). Such fur coats were considered an expensive gift, and were passed down from generation to generation. They were given to daughters as a dowry, which Multinov confirmed in his manuscript (1926: Fol. 20). We found similar fur coats during the work of the Trans-Baikal ethnographic team (Fig. 3).

It was customary among the old residents of Siberia to prepare for their daughters as a dowry not only bright, stitched fur coats in the form of silk khalats, but also sheepskin fur coats. “When I was given in marriage, a fur coat for me was blackened, edged with sheep fur. It went straight down. We tanned the sheepskin ourselves”, recalled T.A. Polomoshnova (born in 1914), a resident of the village of Bolshoi Bashchelak, Charyshsky District, the Altai Territory.

In the Angara region, heat-preserving clothing worn under the fur coat or zipun was a sleeveless jacket- nadevashka . Multinov observed, “There are also women’s warm sleeveless jackets worn under a fur coat or zipun (‘nadevashki’). They were fastened in the front just like cardigans which were specially made for household use and work” (Ibid.: Fol. 23). In Western Siberia, this type of clothing has not been observed.

Going on a long journey, the Siberians, just as the dwellers of all of Russia, put on the tulup . Multinov thus wrote about the Angara tulup , “…this is actually a dokha (a name not particularly popular on the Angara, and used by non-locals) mainly from dog’s fur, with the fur on the outer side. There are also goatskin (wild goat fur), bearskin, calfskin, and composite tulups. <…> During winter trips, the tulup is an irreplaceable thing and warms much better than our Russian fur coats covered with woolen cloth. People sew tulups at homes, and a certain number of long-haired laika dogs are bred especially for them in every household” (Ibid.: Fol. 16).

Multinov noted that bearskin tulups were rare, because they were very heavy. “Deerskin dokhas are almost completely not seen on the Angara, and they are

а

Fig. 3 . Fur coat from the village of Desyatnikovo, Tarbagataisky District, Buryatia, which belonged to N.S. Bannova. Drawings by E.F. Fursova. a – when worn, with folded sleeves; b – unfolded; c – decoration of the sleeves.

b

c

of Tungus origin. An Angara dweller puts on the tulup not only during long journeys ‘in wagons’, but also during short ‘household’ trips (transporting firewood, hay, and wheat, since there are almost no roads in the summer), and therefore it is rarely sewn below the knees” (Ibid.: Fol. 16).

As opposed to the dokha , tulups in Western Siberia were sewn of sheepskin with the fur on the inside. Tulups were worn during snowstorms and blizzards over short fur coats and zipuns ; they were not girdled or fastened, only overlapped from right to left. This type of clothing had a specific element in the form of a high sheepskin fur collar. Old residents sewed fur coats by themselves at home, but they ordered tulups from local craftsmen. According to the expedition field materials, tulups were very long and wide: as old men recalled, “they would hide girls in tulups” (apparently, during the youth festivities of Christmastide).

In the severe cold, a dokha was put over a sheepskin coat or regular coat. In Western Siberia, dokhas , as was mentioned above, were sewn with the fur on the outside. Clothes of this type were worn during long journeys, not only in winter, but also on cold days in the fall and spring. The collection of the RME contains a dokha sewn from 12 dog skins of red light yellow and black color in the village of Novoaleiskoye, Tretyakovsky District, the Altai Territory (collected by I.I. Shangina and I.I. Baranova,

-

1975) . The dokha had a straight design, set-in straight sleeves, and a wide semicircular collar which was tied by strings. The left side overlapped the right; it was fastened with two black buttons. The lining was made of pieces of black and gray satin. According to the collectors, the design of the fur coat, made in 1962, was traditional for this territory (RME, No. 8525-79).

The word khalat for winter clothing was much less common in Siberia than the words fur coat and tulup . According to Multinov, in the Angara region, people used the word khalat for a canvas cover put over a fur coat. “It is somewhat longer than a fur coat and has rather wide sleeves; however, people sew it already when the fur coat is worn out in several places and has no need for being protected. The khalat is always made of homespun canvas, rarely dyed” (Multinov, 1926: Fol. 15). The Trans-Baikal Semeyskie used the word “khalat” for wool-padded clothing covered with semi-silk Chinese fabric. The design of the fabric covering was the same as in fur coats, with gores; the sleeves were made significantly longer than the hands (for example, the length of the sleeves in khalat No. 1327 from MHCPSFE IAET SB RAS is 75 cm, collected by F.F. Bolonev). We were able to examine khalats in the village of Desyatnikovo, Tarbagataisky District, Buryatia (Fig. 4).

Clothing called a khalat, but festive, purchased, which was worn by a dweller of Western Siberia, can

Fig. 4 . Female cotton-padded khalat covered with dense satin, from the village of Desyatnikovo, Tarbagataisky District, Buryatia. Drawing by E.F. Fursova.

be seen on a photograph taken by A.N. Beloslyudov in 1914. The description of the photograph says, “The owner is standing at the door wearing a fancy Kokand khalat, purchased in China during the sale of elk antlers; the village of Fykalka” (Fursova, 1997: 167). Judging by the ethnographic evidence, khalats with or without ornamental decoration occurred in the region only sporadically.

Multinov made a description of men’s legwear, which according to his information always included two layers: long underwear ( podshtaniki ) and outer pants ( sharovary ). “Podshtaniki are made of coarse homemade canvas, not dyed, using calico only as an exception. They are sewn fairly short (for reasons of economy) have a so-called opushka around the upper edge, through which a drawstring is pulled; there are no buttons. Sharovary are made of woolen cloth or plush, dyed linen (‘to resemble those bought at the market’), of cheviot (woolen fleecy fabric – E.F. ), or adreatin ” (Multinov, 1926: Fol. 19). Multinov provided detailed information about sharovary , “Canvas sharovary are dyed mainly the favorite kubovy (blue) color. In addition, they, just like shirts, are dyed brown with oak. The cut of sharovary is straight, not particularly wide. Buttons are sewn onto them, and even pockets are made. Sometimes there are suspenders, but usually, sharovary are girded by a belt with the shirt tucked in or tied with a drawstring. Sharovary are worn tucked into ‘brodni’ waders or boots, but sometimes they are worn over brodni or felt boots. This original method is practiced while walking in deep snow and in order to make it difficult for black flies to get inside the footwear” (Ibid.: Fol. 20).

Pants among the inhabitants of the Yenisei region were also a part of the women’s fishing outfit, which was not typical of everyday clothing among the peasants from other regions (Fursova, 2015: 116). Multinov wrote, “Women’s pants are clothing for fishing with a seine, offering protection from black flies. They are worn under the skirt and often women use men’s sharovary . Of course, in the forest, women also cannot do without pants, which in a funny way come out from under the skirt and are tucked into leather ‘chirki’ shoes and tied with a rope at the bottom, sometimes tucked into stockings*. While fishing with a seine, especially when one has to stand in the water, women flaunt pants tucked into waders or untucked, without a skirt. But in the winter, no matter how cold it was, even on a long journey, the Angara women never put on anything warm under their skirts” (1926: Fol. 23).

In Western Siberia, men going on trips or for longterm work in the open air or in the deep snow, tuck their short fur coats or zipuns into wide chambary pants. We can find a description of chambary from among the Altai Old Believer-“Stoneworkers” in A.N. Beloslyudov, who collected ethnographic materials on the territory of Kazakhstan in 1925. These were working chambary made of white canvas with triangular inserts between the pant legs in the front and back from the village of Bykovo, in the former Semipalatinsk Governorate (RME, No. 5158-23). In 1925, in the Uba River region, Beloslyudov purchased chambary of homemade fabric with yellow, red, and blue strips (RME, No. 5091-10).

In the village of Sekisovka, in the East Kazakhstan Region, the local resident T.A. Babina showed us men’s chembary pants (another variant of chambary ) made of white coarse linen with a low crotch, which were sewn by her mother-in-law in the early 20th century according to the old style. Chembary were used as outer pants; they were worn over long underwear made of striped linen or thinner white linen (FMA, 1978). The Polyaki Old-Believers of the Altai tucked a ponitok robe into chembary made of white canvas, and put a fur coat or short fur coat on top. “A shirt, ponitok, and dokha—people put these on going into the woods”, recalled Ivan Novikov from the village of Soloneshnoye, the Altai Territory (born in 1906, Polyaki Old-Believer).

Multinov described in detail the headwear of the Angara peasants, “The headwear of a peasant in the winter and summer is a warm hat of woolen cloth trimmed on the outside and sometimes on the inside with fur. But often flax tow is simply placed under the lining of the hat… The Angara dweller prefers to wear all year round a hat with loose earflaps dangling while walking. The fur on the hats is predominantly that of dogs, hares (“ushkan”, according to the local dialect), rarely squirrels. In the years of the Civil War, when it was not possible to sell furs at all, squirrel (the entire hat, without even woolen cloth) hats appeared” (1926: Fol. 7). Hats in the shape of papakhas were made of the skins of bears, otters, dogs, squirrels, rarely wolves or calves. “Nansen hats were also made of calfskin. Almost all hats are homemade; very few are market-bought. Women sew them. The distinctive hats made of ‘cherpa’, green fur, apparently that of the seal, should be mentioned. Nansen hats of Tungus origin made of fur from autumn unborn animal fetuses are rare and highly valued” (Ibid.: Fol. 7).

The author noted that the Chaldons “also wear ordinary Tungus deer hats—pointed caps. Very rarely, one might also find among the Chaldons on the Angara Tungus headwear connected to a fur ‘shirt’, as the whole combination is called, and mittens. Combined with ‘luntay’*, such an outfit completely “envelops” its carrier, and leaves only the face open, which suffers little from frost due to habit, and is only lubricated with some lard in the extreme cold. All things of Tungus origin are sewn not with threads, but with deer tendons” (Ibid.).

Multinov provided some information about the headwear, “There are very few fur hats with long ears, the so-called ‘malakhais’, on the Angara. Creative imagination of a hat’s owner is sometimes manifested in the cut of the hats: for example, people may sew a very uncomfortable and heavy bear hat of colossal size… Sometimes there is also a very strange selection of fur in one hat: one ‘earflap’ is of squirrel fur, another of dog fur; the front flap visor is of ‘ushkan’ hare fur. Nansen hats are often supplied with a hard visor of woolen cloth sticking forward, as on a cap. Winter hats on the Angara are worn only by men and children. Women wear them very rarely, unless sometimes while traveling” (Ibid.: Fol. 8). Multinov also mentioned the treukh as the headwear of old men, which was worn by fishers and hunters in the autumn as they went to the woods, and was called a “hunting hat”. “This hat is supplied with a wide ‘tail’ of canvas falling down over the shoulders at the back. This ‘tail’ is called a luzan and has the purpose of protecting from snow off the trees from falling down the shirt… A hunting hat is put on only in the forest and is not worn in the village. There is also a simplified version of that hat as a round, low pointed cap of woolen cloth… also with such a ‘tail’” (Ibid.).

A spherical fox hat, stitched from small pieces of fur, which was purchased from the Trans-Baikal Semeyskie (No. 353, collected by F.F. Bolonev, 1969) is stored in the MHCPSFE IAET SB RAS. This fox hat has earflaps connected using black cotton fabric (Fig. 5). The strings were stitched in such a way that three loops in the shape of a trefoil are formed on the top of the head when the hat is worn with the earflaps in the raised position. It was probably possible to loosen or tighten the hat with their help, depending on the size of the head. At the bottom, the hat is padded with lamb fur; pieces of soft brown felt were laid between the two layers of fur—fox and sheepskin.

A complement to the outfit of the Angara dwellers was the woolen scarf, which was almost never used in Western Siberia. “People knit scarves of wool—it is a necessary attribute of the Angara outfit. Ushkan scarves are white with a black strip at the ends, or the wool is not purely ushkan (hare – E.F. ), but with the addition of sheep wool. There are multi-colored and striped scarves. The length is significant—5–7 arshins. They are worn in a special way: they are wrapped twice around the neck and then they cross over the bulk (body – E.F. ). The width is not significant. The scarves end with tassels. It is interesting that scarves are very often knit by men who do not consider it shameful to be engaged in this handiwork” (Ibid.: Fol. 25).

The harsh climate and black flies did not allow the Angara dwellers to go outside with bare hands even in the summer. Multinov wrote, “Home knit, woolen handgear with one sheath for the thumb are ‘mittens’. There is a hole on the palm for sticking out the index finger when shooting. While working in the open air, a second pair of elk leather ‘verkhonki’ handgear was worn on top of the woolen mittens. Sometimes mittens for durability are sheathed with canvas. There are also ‘kokoldy’ mittens of Tungus origin, made of elkskin with fur… Mittens knit of hare wool have the reputation of being very warm.

Fig. 5 . Fox fur hat with earflaps. MHCPSFE IAET SB RAS, No. 353.

By the way, mittens in general, often with a hole for sticking out the hand for ‘hunting’ convenience are often called ‘kokoldy’. The sheath for the thumb is called the ‘napalok’” (Ibid.).

According to the informants, fur mittens were called mokhnashki in southwestern Siberia. The collection of the RME contains three almost identical pairs of such mokhnashki , from the Altai Territory, discovered by the ethnographers I.I. Shangina and I.I. Baranova (RME, No. 8525-31/1, 2). They are rectangular, sewn from dog fur of white, red, and black color, and are equipped with leather loops (RME, No. 8525-84/1, 2; No. 8525-87/1, 2).

For agricultural work on cold days, on top of the mittens, people put on handgear made of cowhide (“cattle”) leather. Such leather handgear was sewn according to special patterns. “Cattle” mittens were intended for working, so for greater convenience, the thumb was made out of canvas, and the edges of the mittens were made with a leather cuff. In the inventory of Shvetsov’s collection, they are listed as verkhonki —“non-covered handgear with black woolen ‘mittens’” (RME, No. 1343-10).

The wide range of footwear among the Russian dwellers of the Angara region indicates not only the development of home craftsmanship for processing leather and fur, but also the great ingenuity of Siberians, their ability to create comfortable and functional footwear for living in Siberia. Multinov indicated the existence of leather ( brodny , boukuli , bakari ) and fur ( luntai , lunty , lakomei , dyshiki , etc.) types of footwear. Unlike Western Siberia, where the main type of winter footwear, along with obutki and brodni , were homemade felted pimy or katanki , felted footwear on the Angara was exclusively purchased and was called “market-bought”, which means that people did not felt these on their own (Multinov, 1926: Fol. 6).

According to M.P. Berezikova*, in Western Siberian villages, in the winter, in addition to pimy felt boots, people wore self-made leather chirki footwear (another variant charki ) with boot tops and potnik long felt socks. Fishing and hunting footwear of the inhabitants of the Uymon Village in Biysky Uyezd of the Tomsk Governorate in the early 20th century (collected by S.P. Shvetsov) were functionally adapted to winter conditions.

Lunty were boots made of skins taken from goat legs with the fur inside, worn by old men in the winter (RME, No. 1343-6). Kisy were winter footwear made from skins taken from goat legs (RME, No. 1343-7). The presence of a pair of woolen stockings in the collection of Shvetsov indicates that the above footwear was worn with this heat insulating item (RME, No. 1343-5). Woolen stockings could also be worn in the fall and spring with leather koty. In the inventory, the collector thus wrote about them, “Ankle boots with fringes fastened with twine” (RME, No. 1343-9).

Principles of conserving heat in Siberian clothing

According to scientific research, humans have 250,000 skin receptors that perceive cold. This is over six times higher than the amount of heat-perceiving receptors (Osobennosti zashchity cheloveka…, 2008: 133). Conserving heat during the cold season, that is, for almost six months, was an important concern of the descendants of the Russian pioneers in Siberia. In their efforts to protect themselves from the cold, they were guided by the following principles. First, materials with heat-preserving properties, such as wool (woven and nonwoven), fur, and leather were used for manufacturing clothes. Mathematical descriptions of heat transferring processes carried out by scientists have shown that high-volume heat-insulating materials having a porosity of 90–99 %, that is furs, have the lowest heat conductivity (Bessonova, Zhikharev, 2007: 106). Second, people created multilayered outfits thereby forming air layers, which preserved heat between woolen and fur materials. On long trips and travels, old residents put on additional fur clothes, and the location of the fur side was regulated by the principle of oppositeness: inward toward the body (lower layers) and outward as is the case with the outfits of the peoples of the Far North (for example, the Samoyeds, and others) (Prytkova, 1970: 8, 12; Khomich, 1970: 107–109). In this case, clothes such as the fur coat and short fur coat with an interior fur surface acted as the intermediate layer. Third, people sought to ensure, as far as possible, maximum insulation from the outdoor weather conditions. Khalat-like types of clothing were loose, but air circulation was hampered by belts which girdled garments such as the short fur coat, zipun , azyam , etc. in certain situations. Thus, with a high level of snow, they were tucked into the upper pants. Pant legs stretched over felt boots created insulation from the adverse effects of the environment, forming something like a cocoon, which we may call a “Siberian one-piece garment” (Fig. 6). Notably, similar principles of insulating outfits of three layers, like clothes with the fur inside and outside, are actively used today in creating heat protection outfits in the garment industry (Vygodin, 1997: 41).

Analytical dependences of thermal resistance of fibrous materials on temperature, humidity, and the value of mechanical pressure, have been scientifically established. The package should include clothes of sufficiently spacious structures so that the body could

“breathe” and there was no heat loss (Osobennosti zashchity cheloveka…, 2008: 147). It is logical to assume that the “Siberian one-piece garment” for hunting or long trips (together with fur outer clothing: a tulup or dokha ) minimized heat loss, while providing for heat flow from points of the body with higher temperatures to points with lower temperatures.

In the case of a long stay in the snow in the cold, old residents supplemented outfits for fishing and hunting , known in Siberia from the 17th century, with such elements as the luzan , or knee pieces (Bakhrushin, 1951: 88). A specific Siberian feature was the use of some clothing elements of the local Siberian peoples (for example, of the Evenks in the Angara region) in the outfits for fishing and hunting, and women wearing men’s legwear.

It should be noted that aesthetic qualities and compliance with their own traditions were important for Russian old residents of Siberia in addition to heatpreserving properties of the outfit. For this reason, everyday and festive complexes of winter clothing did not include the types of clothes of the indigenous peoples: for example, fabric made with one-piece shoulders (like that of the peoples of the Far North), hoods, or fur footwear.

Conclusions

The variety of categories and types of winter clothing made from various materials and using various methods reflects the experience of previous generations of people coming to Siberia from northern, northeastern and southern regions of European Russia. Numerous testimonies have shown that migrants to Siberia, including those coming from Southern Russia, arrived in outfits appropriate for the local climatic conditions. Such types of clothes as the tulup , short fur coat, zipun , and other clothing with high heat-preserving properties were well known not only to Northern Russian settlers, which was natural, but also to peasants from Southern Russia. Thus, the inventory of the outer clothing of peasants from the Trubchevsky, Bryansky, and Karachevsky Uyezds of the Orel Governorate mentions such clothes as korset , zipun , chekmen , polushubok , svita , and tulup (RGO Archive. Division 27, Inv. 1, No. 18, fols. 112–117). The principle of layering to enhance thermal protection has long been known among the Russians: in the winter, the svita as warm and beautiful clothing was worn over the short fur coat or tulup (RGO Archive. Division 27, Inv. 1, No. 18, fols. 117–118).

Such manifestations of “Siberian courage” as working in the cold without hats and mittens, refusing to wear scarves, putting on the outer garment over one shoulder, in one sleeve and so on reveals the good health and hardiness of the Siberian dwellers in the late 19th to

Fig. 6 . Woman wearing a khalat covered with plush (velvet), and man wearing a “Siberian one-piece garment”. Altai, 1912. Fragment of a photograph by A.E. Novoselov.

early 20th centuries. Light clothing for winter work (half-woolen shabur , ponitok , etc.) were heat treated: for making them warm they were preheated on the stove. Temperature changes in the cold season and winter thaws determined the appearance of manifold variants for winter clothing and various words for it, falling within a limited amount of types, which nevertheless ensured comfortable living conditions throughout the entire cold season. This excluded cooling of the body and consequently the occurrence of cold-related and other diseases.