Use of parts of ram carcasses in the funerary practices of the Baikal region population in the 13th–14th centuries

Автор: Kharinsky A.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.51, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

In the 13th and 14th centuries, there was a custom of placing parts of a ram/sheep carcass in the grave as an offering in the Baikal region. Materials from three areas, which were then parts of the Mongol Empire, are described: southeastern Trans-Baikal, northern Khövsgöl, and southern Angara. Graves are described with a focus on sheep bones, their composition, and location in the grave. In the southern Trans-Baikal, the shank was usually placed near the buried person’s head. Scapulae and vertebrae are much less frequent than shank bones. The latter are most often found under the human pelvic bones or under the upper femur. In the Khövsgöl area, a ram’s shank was placed near the deceased person’s arm or leg. On the Angara, a ram’s head—or the entire dorsal part—was placed near the deceased’s legs. In the Sayantui type burials, located south of Lake Baikal and representing the Mongols’ funerary tradition of the imperial period, the most common offering was a ram’s shank, placed upright. Elsewhere in the Baikal region, other ways of arranging parts of a ram carcass are observed, apparently because of the absence of the Mongol population and its elite in those areas.

Mongol Empire, Baikal region, Sayantui funerary rite, ram bones, shank bones, vertebrae

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146827

IDR: 145146827 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2023.51.1.146-153

Текст научной статьи Use of parts of ram carcasses in the funerary practices of the Baikal region population in the 13th–14th centuries

At the beginning of the 13th century, the region south of Lake Baikal became part of the Mongol Empire. This event significantly affected the various aspects of life of the local population, including their funerary rite. The economic structure and cultural traditions of the steppe region population differed only slightly from the founders of the empire—the Mongols. This made it easier for the locals to acquire new cultural trends common among the titular nation, which after some time spread nationwide.

One of the common features for a significant part of the burials in imperial territory, including the Baikal region, is the presence of ram/sheep skeletal remains in the grave. In various proportions, these included primarily shank bone, as well as scapulae and bones of dorsal part of the carcass. The custom of placing a ram’s shank in the graves probably had both utilitarian and sacral significance. Moreover, ram’s hind leg, placed upright in the grave, is considered by a number of researchers as the most important cultural element, characterizing the Mongolian milieu in the first half of the 2nd millennium AD. For example, N.V. Imenokhoev attributed the medieval burials with the ram/sheep shank bones to the archaeological culture of the 8th–14th centuries, which territory covers part of the Irkutsk Region, the Olkhon Region, western and eastern Trans-Baikal, and northern Mongolia (1988). This culture was proposed to be called Early Mongolian (Konovalov, 1989; Imenokhoev, 1989, 1992).

In order to understand how stable was this tradition of placing a ram/sheep hind leg in burials of the 13th– 14th centuries in the Baikal region, let us compare materials from the three regions of the area: the valleys of the Urulyungui and Onon rivers in the Trans-Baikal Territory, the valley of Angara River in the Irkutsk Region, and from the northern shore of Lake Khövsgöl in Mongolia.

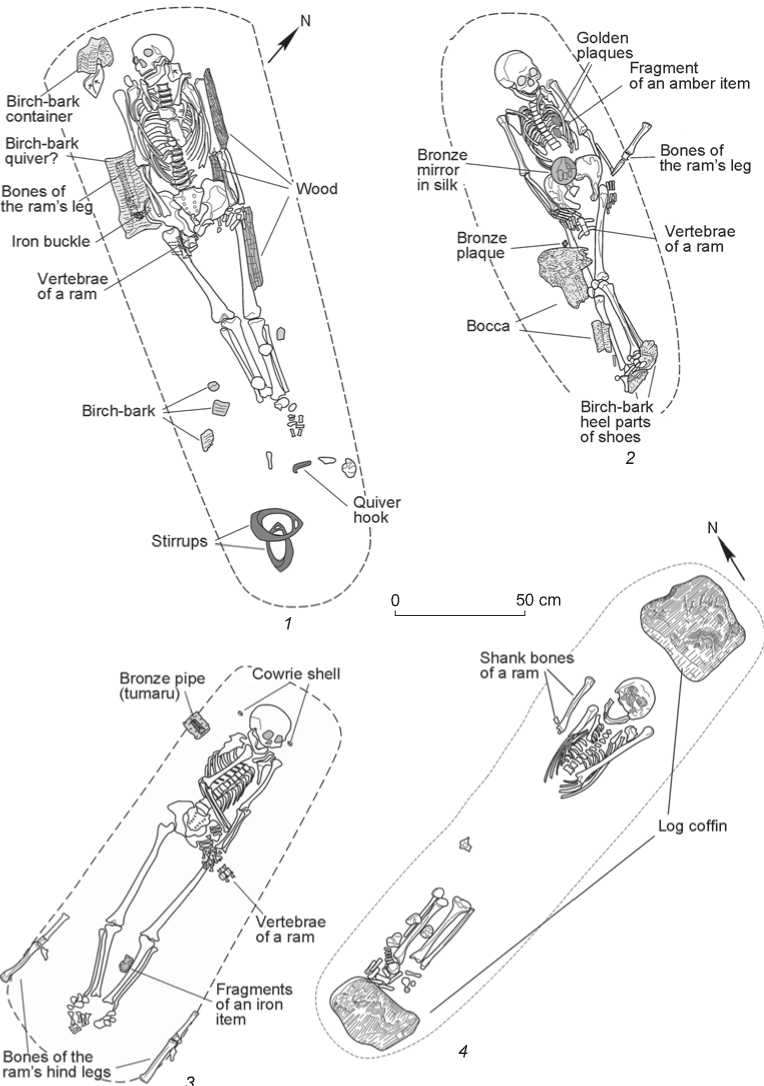

Burials with ram bones

In the 13th–14th centuries, in the southeastern TransBaikal, the unification of the funerary ritual is noted. Its main elements include the placement of parts of a ram/ sheep carcass in the grave, which is well recorded in the materials of the Okoshki cemetery, located on the left bank of the Urulyungui River (Kharinsky et al., 2014). A sheep shank, forming a single unit with the heel and talus bone, is most often found in the burials of the necropolis. The shank of the animal was placed near the wall of the grave, to the right of the head of the deceased (Fig. 1, 1 ). Most of the graves of the cemetery were looted. However, despite the loss of the anatomical integrity of the human skeletons, the bones of the ram’s leg retained their position in the northwestern corner of the grave-pits (Fig. 1, 2 ). In the graves of the Okoshki cemetry, the shank bone of the animal is turned with the upper epiphysis down. The body of the deceased was placed in an intra-burial structure—a wooden frame, a coffin, a log, or a stone sarcophagus, while the ram’s shank was put outside, most definitely at the northwestern corner of the structure (Fig. 1, 3 , 4 ). According to the data from burial 17, the shank was installed in the pit even before the intra-burial structure was placed there: under the weight of the coffin, the bone broke, and part of the shank was under it (Kharinsky et al., 2019). In some cases, the leg bones of the ram were raised above the bottom of the grave-pit by 20–25 cm and were at the level of the facial area of the buried, which suggests the presence of a special small step.

The placement of the ram’s shank at the head of the deceased was also recorded in the burials in the Onon River valley. In burial 2 of the Budulan cemetery, a sheep shank was found in the northeastern part of the grave, near the skull of the buried human (Aseev, Kirillov, Kovychev, 1984: 46, 47). At the Chindant cemetery, ram bones were found near the northeastern end of the log coffin in burial 6; on the cover of the log coffin, at the same end, in burial 10; and on a stone slab covering a wooden coffin, at the northern end, in burial 11 (Ibid.: 49–56). In burial 10 of the Ulan-Khada III cemetery, a ram’s leg bone was discovered in the northwestern corner of the grave, outside the log coffin (Ukhinov, 2014). A similar practice was noted in the Onon River valley also before the 13th century.

In burials 1 and 7 (Fig. 1, 6 , 7 ) of the Malaya Kulinda cemetery (excavations of 2003), dated back to the 11th– 12th centuries, ram’s shanks placed upright were found near the northeastern corner of the coffin (Kovychev, 2004b; Kovychev, Dushechkina, 2004), as well as in another group of graves of this burial ground, excavated in 1980 and attributed by E.V. Kovychev to the12th–13th centuries (2004a: Fig. 17) (Fig. 1, 5 ), which suggests a significant stability of this tradition.

In addition to the ram’s shank bones, in the 13th– 14th centuries burials of the southeastern Trans-Baikal, ram’s lumbar vertebrae and scapulae are also found. At the Okoshki cemetery, vertebrae were discovered in five burials (in four, they retained their original position), and scapulae in two burials. In burial 49, the scapula was located vertically near the northeastern corner of the log coffin in which an infant was buried, and the vertebrae were located under the bottom of the log coffin (Fig. 1, 3 , 4 ).

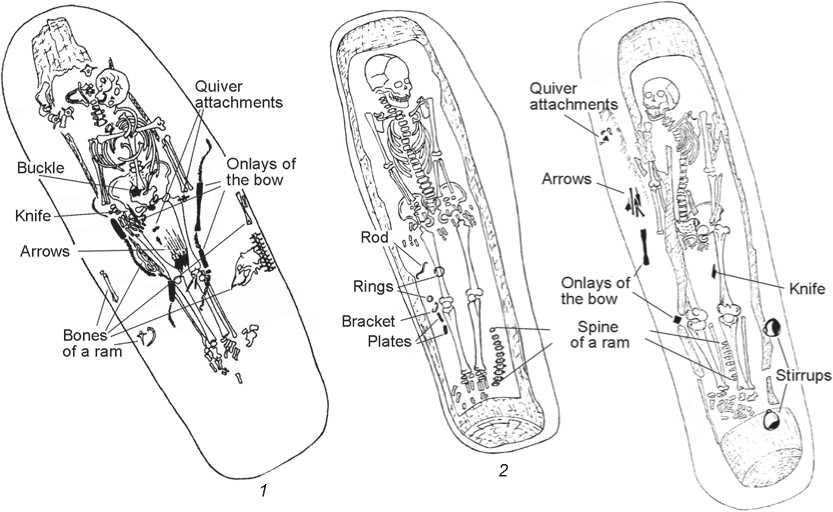

Despite the fact that during the imperial period, in most of the Baikal region, common burial traditions were formed, known as Sayantui type burials (Kharinsky, 2018), a certain individuality was preserved in some of its areas. This included the placement of the ram’s carcass parts into the grave, along with the deceased. One of these areas was the northern shore of Lake Khövsgöl (Mongolia). To date, five undisturbed and six partially disturbed burials of the 13th–14th centuries have been excavated there, which yielded sheep bones (Kharinsky, Erdenebaatar, 2011, 2019; Orgilbayar et al., 2019; Orgilbayar…Bayansan, 2019).

In burial 2 of the Zuun-Khyaryn-Denzh-1 cemetery, the deceased was buried in an extended supine position, with his head to the northwest (Fig. 2, 1 ). Near the bones of the right hand, there was a rectangular piece of birch-bark, possibly the remains of a quiver. Under it, the bones of the hind leg of the ram (tibia, talus, and heel bone) were found in anatomical order, which were located horizontally and directed with their upper parts to the northwest. Under the right ischium of the pelvis of the deceased, two lumbar vertebrae of a sheep were found adjoining each other, with their front parts to the northwest.

At the cemetery of Urd-Khyar-1, in burial 9, the deceased was buried in a log coffin in an extended supine position, with his head to the northeast. Between the log and the wall of the grave-pit, southeast of the upper part of the left human femur, there was the metacarpal bone of a sheep vertically set with its lower epiphysis upwards. Three ram’s lumbar vertebrae were found under the right femur of a human. During the burial, they were in an articulated state, and were oriented with their front parts to the west.

Three burials with ram’s bones were excavated at Urd-Khyar-2. In burial 23, the deceased was buried

Heel bone of a ram

Heel bone of a ram -

Heel bone of a ram -

Scapula «of a ram

Earrings

Shank bone — of a ram

Skull

Scissors

Three ram’s vertebrae — under the log coffin I

Knife

Silk fabric

Birch-bark

'3

В

Heel bone of a ram :^

Cover of the log .coffin

50 cm

1 m

coffin

Heel bone of a ram

Heel bone of a ram

Heel bone of a ram

Knife

^Scapula cf a ram

f- Skull

Vertebrae of a ram

Birch-bark quiver

Fig. 1. Burials with sheep bones in the southeastern Trans-Baikal.

1–4 – Okoshki cemetery: 1 – burial 20, 2 – burial 48, 3 , 4 – burial 49; 5 – Malaya Kulinda, 1980, burial 22 (Kovychev, 2004a: Fig. 17);

6 , 7 – Malaya Kulinda, 2003 (Kovychev, 2004b: Fig. 1): 6 – burial 1, 7 – burial 7.

Wood

Восса

Quiver hook

/ Vertebrae / of a ram

Fragments of an iron item

A Vertebrae

\of a ram

Bronze mirror" in silk ,

Bronze plaque

__Bones of \ the ram's leg

\ Golden

4-plaques

V' Fragment к //\ z of an amber item

Birch-bark / heel parts of shoes

Iron buckle

Birch-bark

Stirrups

Bones of ^ the ram's leg_

Birch-bark container

Birch-bark quiver? Y

Vertebrae of a ram "

"Cowrie shell

Bronze pipe (tumaru) v ,

Bones of the ram’s hind legs

Log coffin

50 cm

Shank bones of a ram \\

Fig. 2. Burials with ram’s bones on the northern shore of Lake Khövsgöl.

1 – Zuun-Khyaryn-Denzh-1, burial 2; 2–4 – Urd-Khyar-2: 2 – burial 23; 3 – burial 24; 4 – burial 26.

in an extended supine position, with her head to the northwest. She was covered by a wooden ceiling. To the left of the human left hand bones, along the wall of the grave-pit, bones of the ram’s hind leg (tibia, tarsal, metatarsal) were found in anatomical order. They were located obliquely, with their upper epiphyses to the northeast. Between the human femurs, there were two ram’s lumbar vertebrae. During the burial, they were in an articulated state, and were oriented with their front parts to the southeast (Fig. 2, 2).

In burial 24, the deceased was laid in the same way as the previous one, but with his head to the northeast.

In the southwestern part of the grave-pit, along the northwestern and southeastern walls, there were the bones of the ram’s hind legs (tibia, tarsal, metatarsal) in anatomical order. They were located obliquely, with their upper epiphyses to the southwest (Fig. 2, 3). Two ram’s vertebrae were found near the left femur of the buried. During the burial, they were in an articulated state. One meter northeast of the grave, a round pit was located, where the skull and leg bones of a lamb were found. Probably, before burial, they formed a single whole with a skin taken from a killed animal and placed in the pit.

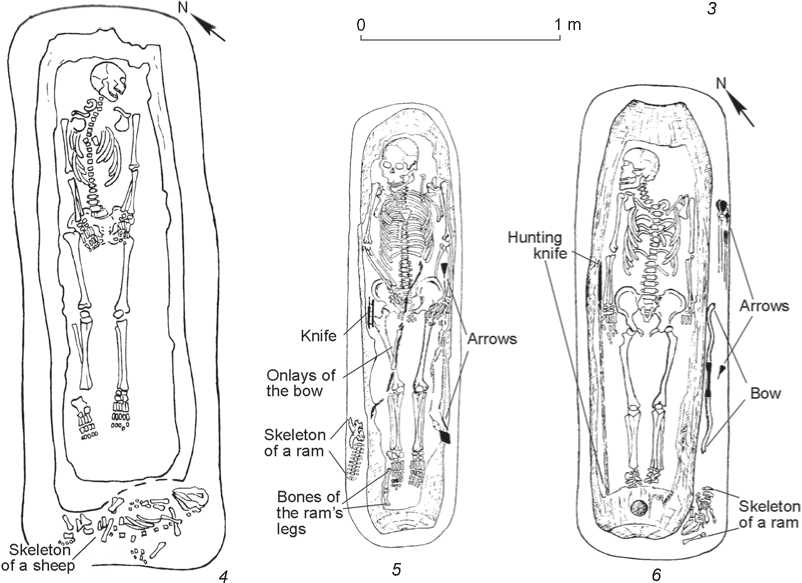

Fig. 3 . Burials with ram’s bones in the southern part of the Angara River valley (Nikolaev, 2004).

1 – Doglan cemetery, burial 15; 2 , 3 – Shebuty III cemetery: 2 – burial 5, 3 – burial 6; 4–6 – Ust-Uda cemetery: 4 – excavation 4, burial 1, 5 – excavation 6, burial 4, 6 – excavation 6, burial 10.

In burial 26, the deceased was buried in a log coffin in an extended supine position, with his head to the eastnortheast. The bones of the middle part of the skeleton were absent. The ram’s tibia and tarsal bones were found to the right of the skull and humerus of the interred (Fig. 2, 4 ). At the time of burial, they formed a single unit, oriented by its upper epiphysis to the east-northeast and located parallel to the human skeleton.

The placement of ram’s bones in the burials of southern part of the Angara River valley differed from those in the southeastern Trans-Baikal and the northern shore of Khövsgöl. At the Doglan cemetery, the ram’s shanks were found in a grave-pit on both sides of the legs of the deceased, whose head was oriented to the northwest (burials 14 and 15). In addition, in burial 15, near the northeastern wall (southeast of the ram’s leg bones), there was ram’s skull and part of its spine, and at the southwestern wall (southeast of the ram’s leg bones) its cervical vertebra and a rib (Fig. 3, 1 ). At the cemetery of Shebuty III, several burials were excavated, in which the deceased were placed in log coffins and were oriented with their heads to the northwest. In each of them, a ram’s spine was found. In burials 5 and 7, it lay near the bones of the lower part of the human left leg (Fig. 3, 2 ), and in burial 6 between the tibia of the deceased (Fig. 3, 3 ). In all the cases, the animal spine was in anatomical order and was oriented in the same direction as the human skeleton (Nikolaev, 2004: Fig. 49, 52, 66–68).

In three burials of the Ust-Uda cemetery, where the deceased were buried in log coffins, skeletons of sheep/ ram were found. In burial 1 of excavation 4, the deceased was oriented with his head to the northeast. The sheep skeleton was located along the southwestern wall of the log coffin, with its skull to the southeast (Fig. 3, 4 ). In burial 4 of excavation 6, the buried was oriented with his head to the north. The ram’s skull and spine were to the west of the southern end of the log coffin. The animal’s skeleton was oriented with its skull to the north (Fig. 3, 5 ). The bones of the ram’s leg were located in the log coffin, along its wall to the southwest of the bones of the human’s right foot. In burial 10 of the same excavation, the deceased was oriented with his head to the northeast. The ram’s skeleton was located at the southwestern end of the log coffin, along its southeastern wall, with its skull to the southwest (Fig. 3, 6 ) (Nikolaev, 2004: Fig. 86, 94, 99).

Discussion

The tradition of placing a vertically installed ram’s shank in the grave was widespread in the Mongol Empire. This element of the funerary rite is primarily typical of the Mongols themselves, but was probably also borrowed by the culturally close peoples. In the south of Siberia, most of the burials of the 13th– 14th centuries with this funerary feature were recorded in the southern Trans-Baikal.

It is still difficult to identify where the tradition of placing a ram’s shank in the grave at the head of the deceased was originally developed. According to E.V. Kovychev, in the Onon River valley, this custom has been already known in the 11th–12th centuries (1981, 2004b). At about the same time, it was practiced in the southwestern Trans-Baikal, in the Selenga River valley. At the Kibalino cemetery of the 11th–14th centuries, seven of the eight excavated graves contained vertically or obliquely arranged ram’s shanks. In four cases, the bone was in the northeastern corner of the grave-pit, in two cases in the northwestern corner, and in one case behind the skull of the buried human. Sheep vertebrae were found in the central part of two burials of the cemetery (Konovalov, Danilov, 1981). Sheep bones were also found in a grave on the right bank of the Selenga River, 1 km from the bridge along the Ulan-Ude – Kyakhta route. At the left clavicle of the deceased, there was a tubular ram’s bone, placed upright, and at the right hand humerus, on the outside, there were three ram’s vertebrae (Aseev, Kirillov, Kovychev, 1984: 34). A paired burial was excavated 15 km east of Ust-Kyakhta, in the Subuktui area. The male skeleton lay in the western part of the grave, the female in the eastern. A vertically standing tubular bone of a ram was found next to the man’s skull, and ram’s vertebrae near the right hand bones. One ram’s vertebra was located at the elbow joint of the woman’s left hand (Ibid.: 36). In burial 1 of the Varvarina Gora cemetery, a ram’s leg bone was placed upright in the northwestern corner of a burial chamber ( domovina ) made of boards, near the skull of the deceased (Ibid.: 38).

Judging by the materials of the 13th–14th centuries burials in the southeastern Trans-Baikal, ram’s shanks were found in about half of them. In most cases (about 90 %), these were placed upright near the skull of the interred person. Sheep scapulae and vertebrae occur in burials much rarer than shanks (Kharinsky, 2015). The latter are most often discovered under the pelvic bones or the upper part of the femurs of the buried.

Funerary rite of inhabitants of the Khövsgöl region in the 13th–14th centuries, as in the southern Trans-Baikal, included the active use of parts of a ram/sheep carcass. In four of the five cases we examined, these were two or three lumbar vertebrae, belonging to the loin part of the animal carcass. It was laid at the bottom of the gravepit before the deceased was placed there. In the funerary practices of Khövsgöl population, the ram’s shank placed upright in the grave near the head of the deceased was not recorded. Here, it was placed in other parts of the gravepit. In two cases, the ram’s shank was located horizontally to the right of the right hand of the deceased, and in one case obliquely to the left of the left hand. Another grave contained two ram’s hind legs, which were located obliquely between the walls of the pit and the legs of the deceased. Near this grave, there was a separate burial of the lamb’s skin, with head and legs. Only in one case, a vertical placement of the lower part of the sheep shank in the grave was recorded, to the left of the left leg of a deceased person.

The Angara burials, where ram/sheep bones were found, belong to the Ust-Talkin culture (11th–14th centuries) (Nikolaev, 2004: 158), widespread in the northern periphery of the Mongol Empire. There was no imperial elite, nor the Mongol population here, which contributed to the preservation of a number of Ust-Talkin own cultural traditions, including the placing of parts of a ram/sheep carcass in the grave. These were located at the feet of the deceased in the log coffin or outside of it. Unlike the Trans-Baikal and the Khövsgöl region, in the Angara region, a whole sheep carcass or a significant part of it was placed in the grave. The presence of a sheep shank near a human’s skull has not been recorded in the Ust-Talkin culture. One of the most important features of this culture is the construction of separate burials of horses, cows or rams near the graves of people.

Conclusions

Despite the unification of funerary rite in the Mongol Empire in the 13th century, there were still areas in the Baikal region where cultural identity was preserved, including a custom of placing parts of a sheep carcass in the grave. The Sayantui type burials, reflecting the funerary practices of the Mongols of the imperial period, show the custom of placing a ram/sheep shank in a vertical position in the grave, while in other parts of the region there were other traditions. The Ust-Talkin culture people, who represented the easternmost enclave of the Kypchak circle of cultures, placed mainly the loin of a sheep at the feet of the deceased. On the shores of the Khövsgöl, where the Tumats lived, a sheep shank was placed in the grave near the hand or foot of the deceased. The preservation of these local differences was probably due to the absence of the Mongolian population and its elite in the northern peripheral regions of the empire.

Список литературы Use of parts of ram carcasses in the funerary practices of the Baikal region population in the 13th–14th centuries

- Aseev I.V., Kirillov I.I., Kovychev E.V. 1984 Kochevniki Zabaikalya v epokhu srednevekovya. Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Imenokhoev N.V. 1988 Srednevekoviy mogilnik u s. Yenkhor na r. Dzhide (predvaritelniye rezultaty issledovaniya). In Pamyatniki epokhi paleometalla v Zabaikalye. Ulan-Ude: BF SO AN SSSR, pp. 108-128.

- Imenokhoev N.V. 1989 K voprosu o kulture rannikh mongolov (po dannym arkheologii). In Etnokulturniye protsessy v Yugo-Vostochnoy Sibiri v sredniye veka. Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 55-62.

- Imenokhoev N.V. 1992 Rannemongolskaya arkheologicheskaya kultura. In Arkheologicheskiye pamyatniki srednevekovya v Buryatii i Mongolii. Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 23-48.

- Kharinsky A.V. 2015 Kosti barana v zabaikalskikh pogrebeniyakh X-XV vv. In Aktualniye voprosy arkheologii i etnologii Tsentralnoy Azii: Materialy Mezhdunar. nauch. konf., Ulan-Ude, 7-8 apr. 2015 g., B.V. Bazarov (ed.). Irkutsk: Ottisk, pp. 407-415.

- Kharinsky A.V. 2018 Yuzhnoye Pribaikalye nakanune obrazovaniya Mongolskoy imperii. Arkheologiya yevraziyskikh stepey, No. 4: 187-192.

- Kharinsky A.V., Erdenebaatar D. 2011 Severnoye Prikhubsugulye v nachale II tys. n.e. In Teoriya i praktika arkheologicheskikh issledovaniy, iss. 6, A.A. Tishkin (ed.). Barnaul: Izd. Alt. Gos. Univ., pp. 107-124.

- Kharinsky A.V., Erdenebaatar D. 2019 Naseleniye Severnogo Prikhubsugulya (Mongoliya) v XIII- XIV vv.: Po pismennym i arkheologicheskim dannym. In Azak i mir vokrug nego: Materialy nauch. konf., Azov, 14-18 okt. 2019 g. Azov: Izd. Azov. muzeya-zapovednika, pp. 212-216.

- Kharinsky A.V., Nomokonova T.Y., Kovychev E.V., Kradin N.N. 2014 Ostanki zhivotnykh v mongolskikh zakhoroneniyakh XIII- XIV vv. mogilnika Okoshki I (Yugo-Vostochnoye Zabaikalye). Rossiyskaya arkheologiya, No. 2: 62-75.

- Kharinsky A.V., Rykun M.P., Kovychev E.V., Kradin N.N. 2019 Mongolskiy mogilnik serediny XIII - nachala XV v. Okoshki 1 v Yugo-Vostochnom Zabaikalye: Konstruktivniye i antropologicheskiye aspekty. In Genuezskaya Gazariya i Zolotaya Orda, vol. 2, S.G. Bocharov, A.G. Sitdikov (eds.). Kazan, Chisinau: Stratum Plus, pp. 69-106.

- Konovalov P.B. 1989 Korrelyatsiya srednevekovykh arkheologicheskikh kultur Pribaikalya i Zabaikalya. In Etnokulturniye protsessy v YugoVostochnoy Sibiri v sredniye veka. Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 5-20.

- Konovalov P.B., Danilov S.V. 1981 Srednevekoviye pogrebeniya v Kibalino (Zapadnoye Zabaikalye). In Novoye v arkheologii Zabaikalya. Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 64-73.

- Kovychev E.V. 1981 Mongolskiye pogrebeniya iz Vostochnogo Zabaikalya. In Novoye v arkheologii Zabaikalya, I.I. Kirillov (ed.). Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 73−79.

- Kovychev E.V. 2004a Dalekoye proshloye Poononya. In Istoriya i geografia Olovyanninskogo rayona. Chita: Poisk, pp. 4-95.

- Kovychev E.V. 2004b Rannemongolskiye pogrebeniya iz mogilnika Malaya Kulinda. In Tsentralnaya Aziya i Pribaikalye v drevnosti, iss. 2. Ulan-Ude: Izd. Buryat. Gos. Univ., pp. 181-196.

- Kovychev E.V., Dushechkina T.A. 2004 Mongolskiye pogrebeniya Poononya (noviye danniye po pogrebalnomu obryadu drevnikh mongolov). In Traditsionniye kultury i obshchestva Severnoy Azii s drevneishikh vremen do sovremennosti: Materialy XLIV Region. arkheol.-etnogr. konf. studentov i molodykh uchenykh. Kemerovo: Izd. Kem. Gos. Univ., pp. 256-257.

- Nikolaev V.S. 2004 Pogrebalniye kompleksy kochevnikov yuga Sredney Sibiri v XII-XIV vekakh: Ust-Talkinskaya kultura. Vladivostok, Irkutsk: Izd. Inst. geografi i SO RAN.

- Orgilbayar S., Kharinsky A.V., Erdenebaatar D., Mandalsuren N. 2019 Mongol-Orosyn khamtarsan “Tov Aziyn arkheologiyn shinzhilgee-1” tosliyn Khovsgol aymgiyn Khankh sumyn nutagt yavuulsan maltlaga sudalgaany azhlyn urdchilsan ur dungees. In Mongolyn arkheologi-2018: Erdem shinzhilgeeniy khurlyn emkhetgel. Ulaanbaatar: pp. 140-146.

- Orgilbayar S., Kharinsky A.V., Erdenebaatar D., Mandalduren N., Bayansan P. 2019 Mongol-Orosyn khamtarsan “Tov Aziyn arkheologiyn shinzhilgee-1” tosliyn Khovsgol aymgiyn Khankh sumyn nutagt yavuulsan maltlaga sudalgaany azhlyn urdchilsan ur dungees. In Mongolyn arkheologi-2019: Erdem shinzhilgeeniy khurlyn emkhetgel. Ulaanbaatar: pp. 200-207.

- Ukhinov Z.C. 2014 Pogrebeniya XII-XIV vv. mogilnikov Ulan-Khada I i III v Vostochnom Zabaikalye. In Sovremenniye problemy drevnikh i traditsionnykh kultur narodov Yevrazii: Tezisy dokl. LIV Region. arkheol.-etnogr. konf. studentov, aspirantov i molodykh uchenykh, Krasnoyarsk, 25-28 marta 2014 g., P.V. Mandryka (ed.). Krasnoyarsk: Sib. Feder. Univ., pp. 194-196.