Wearing folk costumes as a mimetic practice in Russian ethnographic field studies

Автор: Kucherskaya M.A.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnography

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.47, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145408

IDR: 145145408 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2019.47.1.127-136

Текст статьи Wearing folk costumes as a mimetic practice in Russian ethnographic field studies

A clear shift in the scholarly research of folk poetry and peasant life occurred in the mid 1830s–early 1840s, in the period of the revived public debate about the specific nature of the Russian national identity (Pypin, 1891: 1–2). However, despite the fact that ethnographic research entered a new stage of development, collectors faced serious difficulties, primarily, distrust on the part of peasants. To overcome the suspiciousness of the informants, ethnographers began to dress in folk costumes. This practice was most consistently applied by one of the first professional collectors of folklore in Russia Pavel Yakushkin, who walked around the villages wearing a red shirt and plush trousers under the guise of a peddler. According to the recollections of his contemporaries, Yakushkin, “bought goods on ten rubles, brought a carrying basket, and headed for the villages to collect traditional songs” (Leikin, 1884: LXIX).

This article attempts to reconstruct the sources behind the practice among folklore collectors in the mid 19th century of changing clothes to traditional outfits, which has not yet been described in detail by the historians of Russian ethnography. The influence of this practice on the further development of ethnography and later behavioral strategies of intellectual-populists who wanted to get close to the peasants and workers, are also analyzed.

Social mimicry by Pavel Yakushkin

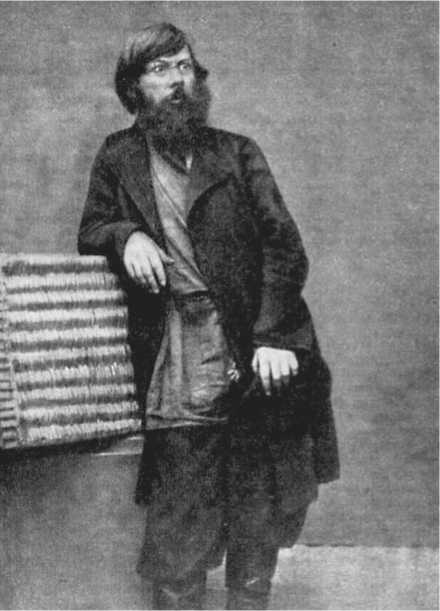

Pavel Yakushkin “walked around as a peasant”, “but wore glasses, because of which real peasants did not want to recognize him as one of their own, but thought that he

Fig. 1. Pavel Yakushkin. Photograph of the late 1860s. Nizhny Novgorod (from the collection of the State Museum of the History of Russian Literature).

just with a rope. I rarely saw him wearing a peaked cap” (1884: LXIX) (Fig. 1). The soiled caftan and shirt girded with a rope, which Pavel Yakushkin wore not only on expeditions, but also in the capital city, indicates that he obviously felt more comfortable wearing such an outfit. This is confirmed by the recollections of N.S. Leskov who studied with Yakushkin in the same Gymnasium, although a bit later, who claimed that negligence in clothing and hairstyle was typical of Pavel Yakushkin even in his young years (Leskov, 1958: 72).

For Yakushkin, traditional clothes, just as the “peasant words” he used, were obviously a marker of his closeness to Russian peasants. However, in popular aesthetic notions, untidy clothes were perceived as indecent (Zlydneva, 2011: 548). Only working clothes directly during work might look dirty on a working person, but not everyday clothes and particularly not festive clothes. Thus, the impression of “disguise” was probably reinforced by the untidiness of Yakushkin’s outfit.

It is quite possible that Pavel Yakushkin would have started to wear peasant clothing even without starting to collect folklore: his engagement with the traditional culture only seemed to legitimize his natural inclination and self-perception. All this, however, does not explain why Yakushkin consciously played the role of a peddler, selling dry goods to peasants. Yet, the idea of dressing as a peddler did not belong to him, but was suggested by his teachers of the collection of ethnographic materials.

was ‘someone who put on a disguise’” (Leskov, 1958: 73). Yakushkin was the son of a nobleman, the retired Lieutenant I.A. Yakushkin, and a peasant serf woman. He graduated from the Orel Gymnasium and Department of Physics and Mathematics of the College of Philosophy at Moscow University (Balandin, 1969: 16–18), became interested in collecting, and eventually became an educated writer and professional researcher of folk culture and everyday life. Thus, the definition of “disguised” is fully applicable to Yakushkin: he indeed put on a disguise and played a role.

Importantly, after returning from his expeditions, Pavel Yakushkin continued to wear the same peasant clothes. N.S. Leikin gave its detailed description, “He wore the same outfit in St. Petersburg: people recognized him from his traditional Russian outfit and glasses. It was not the dashing Russian ballet costume worn by some of the Slavophiles of that time, who would flaunt lacquered boots, sarcenet shirts, and hats with peacock feathers. Yakushkin’s caftan was made of the coarsest woolen cloth, always soiled; his boots in most cases were worn out and dirty; a low hat of lambskin was on his head in the winter and summer; his red kumach [‘calico’ – translator’s note ] shirt was girded with a simple belt containing a written prayer or sometimes

Sources of the social mimicry of Pavel Yakushkin

In his years of study at Moscow University, Pavel Yakushkin met with Petr Kireevsky and Mikhail Pogodin, under whose influence his interest in traditional lore and everyday life took shape. Since 1843, the student Yakushkin started to gather folklore for Kireevsky’s complete collection of folk songs (Azadovsky, 1958: 328– 338). In 1844, his first publication entitled “Folk Tales about Hoards, Robbers, Sorcerers, and Their Actions, Recorded in Maloarkhangelsky Uyezd” appeared in Moskvityanin Journal (No. 12) which was published by Pogodin. It included some of the materials collected on his first two expeditions. It was Pogodin who gave special instructions to Yakushkin on how to collect folk songs. These instructions have been preserved in the work of N.P. Barsukov (1896: 23–25).

Pogodin gave Yakushkin many recommendations. He pointed that songs should be recorded “the way they were sung”, “without any corrections”, and that preference should be given to historical and ritual songs, as well as spiritual poems. In fact, the same instructions essentially contained a detailed scenario of the forthcoming expedition: to walk around villages

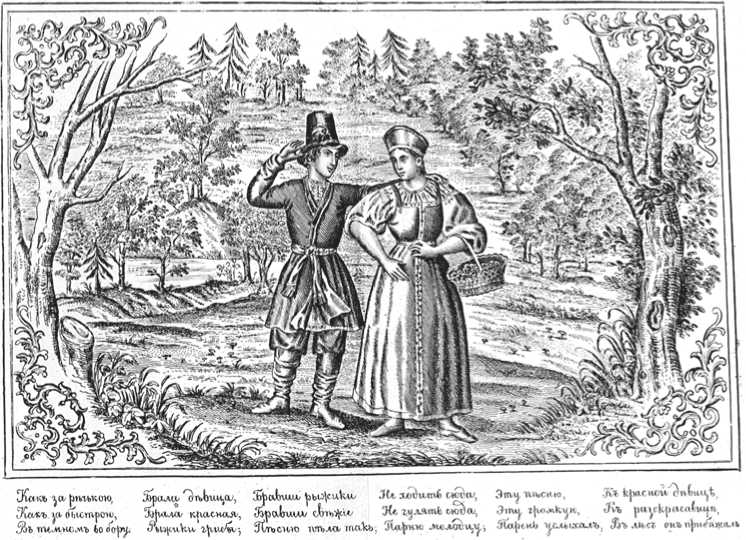

Fig. 2 . Popular print of a peasant man and woman, 1850 (from the collection of the Department of Rare books and Manuscripts at the Scientific Library of the Lomonosov Moscow State University).

in peasant dress disguised as a peddler and use smallscale trade as a reason to get acquainted with peasants. “Do not say anywhere that you came with a certain purpose—to collect songs, or anything else. Gradually, inadvertently, in passing, you should accomplish it, not showing yourself to be smart, and not feeling uncomfortable by any stupidity or vulgarity. It seems that it would be best”, Pogodin wrote, “if you were to grow a beard, put on a kumach shirt with the collar off center, gird your caftan with a sash, and stock up with various small goods: earrings, rings, beads, hair and patterned ribbons, ringshaped dry rolls, and gingerbread, and start trading in the villages. Then you would have the best excuse to begin your acquaintance with village singers” (cited after (Balandin, 1969: 25–26)). Pavel Yakushkin followed this advice to the letter: he grew a beard, bought goods, and started to go around the villages with a carrying basket, selling beads and rings to peasant women, and giving gingerbread to children (Fig. 2). In addition, it is true, he treated the men with “wine” (vodka), so they would sing more willingly. It was this practice that obviously led the collector, who did not shy away from the common merriment, to quite predictable and sad consequences.

It is curious that long before that, in 1838, P.V. Kireevsky, N.M. Yazykov, and A.S. Khomyakov also compiled a brief guide for folklore collectors, “On Collecting Folk Songs and Poems”, which was published in Simbirskiye Vedomosti*. They encouraged their enlightened contemporaries to collect folk songs and poems, “these precious remnants of antiquity”, and formulated the basic principles for recording the texts, “Songs that are sung among the people should be recorded word for word, all without exception, indiscriminately, disregarding their contents, brevity, clumsiness, and even the apparent lack of sense” (Parilova, Soimonov, 1968: 49; Soimonov, 1960: 148). The intersection with the rules set out in the instruction by Pogodin is obvious, but the earlier “song proclamation” by Kireevsky, Yazykov, and Khomyakov did not have a single mention about dressing as a peddler.

Such a manner of recording folklore was unique for Russia in the 1840s–1850s. This is indicated by one of the first biographers of Yakushkin, the famous ethnographer and writer S.V. Maksimov, “It must be remembered that Yakushkin’s departure was new—no one had laid such a path before him. There was nowhere to study the methods; no one had yet dared to take such bold, systematically calculated steps and such daring actions—meeting face-to-face with the people. According to the spirit of that time, the plan of Yakushkin can be considered positive madness which, at least, could be justified only by the passions of youth. <…> Deciding to collect authentic folk songs far from being a child, but almost thirty years of age*, Yakushkin made a major literary step, without knowing it, and in any case he treaded the path on which it would be already a little easier for others to walk” (1884: XXIII).

Calling Yakushkin’s departure “new”, Maksimov obviously had in mind that none of Yakushkin’s predecessor-collectors (albeit not too numerous) (Azadovsky, 1958: 42–112) changed their clothes to look like a peddler. Nevertheless, the instructions of Pogodin looked surprisingly well-polished, filled with confidence that this was the exact way that songs should be collected, although despite all his enthusiasm for folklore Pogodin did not put on traditional Russian clothing, much less did he sell ribbons and ringshaped dry rolls in the villages. Thus, the confidence of Pogodin must have been based not on personal experience, but on completely different sources.

The influence of the Slavophiles and P.V. Kireevsky

According to Barsukov, the instructions cited above were compiled “in the forties” (1896: 22–23); their dating is not difficult to clarify. Pogodin regretted that Yakushkin did not even want to complete his university course, preferring to go on a journey immediately. This means that this happened in the last year of his studies, that is, in the 1844/45 academic year. Yakushkin’s debut story, “Folk Tales about Treasures, Robbers, Sorcerers and Their Actions…” was published in the 12th issue of the Moskvityanin Journal in 1844. At the end of the publication, Pogodin reported, “The author, Yakushkin, a student of Moscow University, intends to go on a trip across all of Russia to collect the remnants of our national spirit”. Apparently, shortly thereafter, he wrote his instructions to his student, most likely in 1845. Precisely in the mid 1840s, the Slavophiles introduced the fashion of wearing a traditional Russian outfit and beard.

K.S. Aksakov was the first who grew a beard and dressed in the Russian traditional clothes; A.S. Khomyakov grew his beard in the fall of 1845 (Mazur, 1993: 128). Aksakov sewed himself a “svyatoslavka” (an Old Russian zipun ‘homespun coat’ with long flaps) for himself, wore an old-fashioned “murmolka” hat, boots, and a red shirt. His example was followed by Khomyakov and I.S. Aksakov. As is well known, the attempts of the Slavophiles to testify to their respect for the Russian national idea in such a way mostly caused ridicule. The famous joke of P.Y. Chaadaev, mentioned by

A.I. Herzen in “My Past and Thoughts”, that people on the streets took K.S. Aksakov for a Persian, is one of the numerous testimonies of public skepticism to the Slavophile venture (Herzen, 1956: Vol. 9, 148) (see also (Chicherin, 1929: 239–240)). The caustic review by the censor A.V. Nikitenko concerning the public appearance of Khomyakov in a traditional outfit (1893: 29) is also known (see also (Kirsanova, 1995: 138–139)). However, his record of the meeting dates back to January 1856—long since the time when the fashion was introduced. Thus, the idea of dressing in peasant clothes was probably taken by Pogodin from the Slavophiles, with whom he was close.

Kireevsky, who was the second mentor of Pavel Yakushkin in folklore collecting and had no less influence on him than Pogodin, also dressed simply and talked with peasants. “A nobleman who does not serve, is always keeping company with simple people, neglects all rules of haut ton, dresses in a svyatoslavka, with a bob haircut”— this is how the portrait artist E.A. Dmitriev-Mamonov, who was close to the Slavophiles, described Kireevsky (1873: 2492–2493).

The reasons why folklore collectors and Slavophiles dressed in traditional outfits were different. The Slavophiles in such a manner sought to emphasize the value of the Russian national idea, to visibly mark the connection with the pre-Petrine time, as well as to emphasize personal freedom and the right to dress according to one’s desire and taste. Conversely, Pogodin offered Yakushkin this kind of mimicry for pragmatic reasons in order to inspire confidence, have the opportunity to engage in conversation with peasants, and therefore, become closer to the informants, and record folk songs more productively. Local dwellers could be suspicious about a collector who did not bother to disguise himself. Pogodin understood this well. Misadventures, which Kireevsky experienced during his trips gathering songs, were most likely known to him as well. Here is a description of one such failure of the famous collector in Ostashkov.

“I imagined”, wrote P.V. Kireevsky to N.M. Yazykov on September 1, 1834, “that I would find back country, but instead I found almost the most educated uyezd town in Russia, in which every blacksmith and every gingerbread maker reads ‘A Thousand and One Nights’ and was already ashamed of bearded songs, but sang: ‘Who could love so passionately’ and even ‘The dashing troika is riding full tilt’… I had hope in the outskirts and lived there for over two months, driving around to village fairs. And in fact a lot of curious things could have been gathered in that uyezd, but not in the circumstances in which I was there. To succeed, I needed: 1) to have some outside excuse for living in Ostashkov and 2) acquaintance with the landowners, but I had neither of the two and therefore not only among the common people, but even in the local beau-monde I was feared like the plague, first imagining

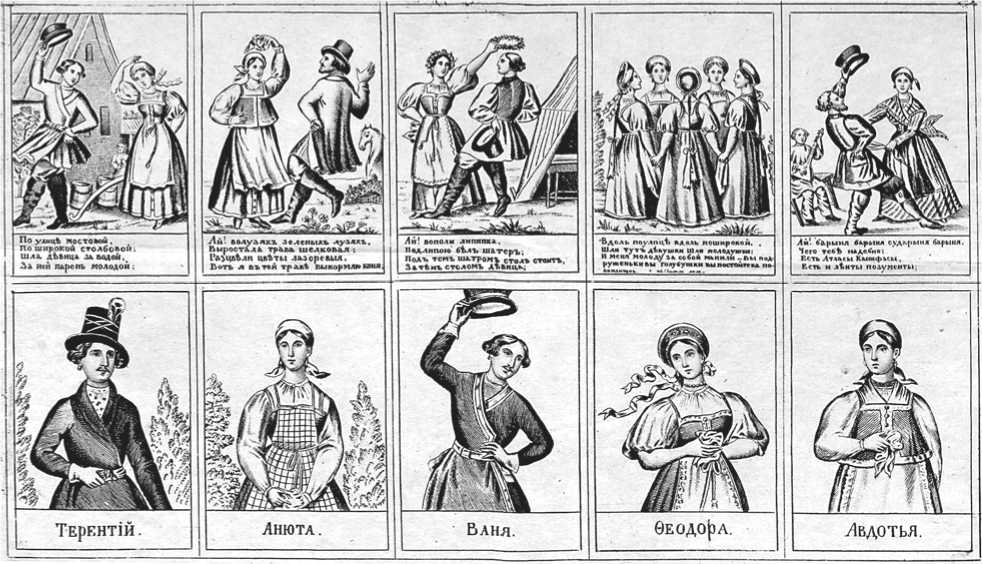

Fig. 3 . Popular print of peasants, 1850 (from the collection of the Rare Books and Manuscripts Department at the Scientific Library of the Lomonosov Moscow State University).

me to be a spy and then a Carbonarist. Therefore, I had a lot of hilarious, most quixotic adventures happening to me (more on them later), but gathering songs was a complete failure” (Kireevsky I.V., Kireevsky P.V., 2006: 123)*.

Interestingly, M.P. Pogodin himself, although he traveled extensively around Russia and was seriously interested in traditional culture, rarely visited peasant houses, starting with a visit to the Governor and continuing with a visit to the Bishop (Balandin, 1969: 144). It was risky for a landowner to go around wearing peasant clothes; this led to conflicts with the police. Yakushkin survived many of them, and the famous Pskov story was only the most sensational in the long series of his misadventures (Yakushkin, 1986: 141–153). Meanwhile, Professor I.M. Snegirev collected folklore wearing his official uniform, and the head of the 3rd Department V.A. Dolgorukov in one of the internal documents referred to his experience as successful (Balandin, 1969: 126). Once, while collecting songs from the people, Kireevsky was “dragged by the collar” by a district officer (Pogodin, 1859).

Another similarity in the strategies of collecting folklore by Kireevsky and Yakushkin was payment for songs. Yakushkin sold his goods for almost free; he basically gave peasants scarves and earrings as gifts, and would often buy vodka for everyone; this livened up people’s merriment and therefore increased the number of recorded texts (see, for example, a description of one of his early travels (Yakushkin, 1986: 448–449)). He could have adopted the practice of paying for the songs which he heard from Kireevsky, who, according to his mother A.P. Elagina, “gathered beggars and old men in Ostashkov and paid them money for listening to their non-paradisal songs” (cited after (Rozanov, 2006: 216)) (Fig. 3).

The red shirt of Alexander Pushkin

The Slavophile dressing in the Russian traditional outfit was the actual context that most likely influenced Pogodin’s ideas concerning folklore collection in the popular environment in the 1840s. However, while compiling his instructions for Yakushkin, he could have relied on an earlier source—the experience of his good friend Alexander Pushkin, who also recorded songs and fairy tales. Pushkin was one of the main initiators of compiling a collection, which eventually Kireevsky became occupied with, and the former gave Kireevsky all the recordings of songs he had (Soimonov, 1968).

Pushkin would also dress in peasants’ clothes. This was recalled by his coachman in Mikhailovskoye, the peasant Peter, “He wore a red shirt tied with a sash, wide pants, a white hat on his head: he did not cut his hair or nails, and he did not shave his beard; he cut the hair on the crown of his head a little, and walked around like this” (Parfenov, 1985: 463). There are other testimonies that Pushkin wore a red silk shirt of the traditional Russian cut (Raspopov, 1985: 399). Wearing a peasant outfit, he went to the Svyatogorsky Monastery fair, where he listened to folk songs and fairy tales that beggars sang (Vulf, 1985: 447).

Since Pushkin wore a red shirt and beard not only at fairs, but also in villages and on the road, it can be assumed that it was an artistic, partly non-conformist gesture. In addition, his love for a red traditional shirt could manifest, first of all, an imitation of George Byron, who dressed with the refined carelessness of an aristocrat and dandy, but who also loved to dress in various outfits (from traditional Albanian to monastic), second of all, the tendency toward theatricalization of life, natural for his time (Lotman, 1992), and third of all, the desire to mark an internal kinship with the people, to act with the same logic as Denis Davydov, who in 1812 put on a “peasant’s caftan” and began “to grow a beard” (Ibid.: 276). Pogodin, who was in friendly and business relations with Pushkin, most likely knew about the whims of the poet and could have taken them into consideration.

Thus, by the mid 1840s, when Pavel Yakushkin was about to go on an expedition, a complex of ideas concerning the appearance of the villager had been finally formed among the Russian intellectuals. First of all, the red shirt was selected from out of the entire diversity of traditional Russian clothes, which in the traditional peasant culture was considered festive and in no way everyday clothing. Another attribute of the “peasant’s” appearance was the beard. The reasons for this choice are clear: such marked elements of ethnic identity were extremely vivid, almost theatrical; we can say that the researchers themselves were originators of a cheap popular image of the Russian peasant, offering to consider the folk costume in isolation from real traditions.

The traditional outfit of Achim von Arnim

It is known that the Slavophiles and Pogodin, who was close to them, were formed under the influence of German philosophy, adopting the ideas of Hegel, Schelling, and Schlegel. I.V. Kireevsky personally spoke with Schlegel several times while studying in Germany. Interestingly, the form of collecting songs by the famous German folklorists Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano, the founders of the Heidelberg circle of German romantics, somewhat resembled the form that Pogodin offered to Yakushkin. In their journey along the Rhine bank, which later became legendary (a collection of adaptations of folk songs, “The Boy’s Magic Horn: Old German Songs”, published in 1806–1808, was prepared using the materials collected during this journey), Arnim walked around wearing a simple outfit obviously trying to imitate a villager. Based on her personal recollections of the two friends, Bettina, the sister of Clemens Brentano, wrote, “Arnim looked so clumsy in his too wide outfit. With a sleeve ripped along the seam, a heavy stick and hat from which the torn lining protruded; you were so slim and graceful with a red cap pulled down on thick black curls, a thin cane and interesting snuffbox sticking out of your pocket” (Zhirmunsky, 1981: 67). Thus, Arnim, a nobleman who knew how to dress elegantly, on a journey dressed in simple clothes, as subsequently did Yakushkin, obviously trying to get close to simple dwellers of villages and following his dream of becoming “a poet of the people”.

“The Boy’s Magic Horn” seems to have been known to Pogodin, although there is no direct proof of this. The book “Spring Wreath”, by Bettina von Arnim (the sister of Brentano who then married her brother’s friend Arnim), consisting of correspondence with Clemens during his journey on the Rhine, was published in 1844, when Pogodin was writing his instructions for Yakushkin. However, in a paradoxical way, the famous collection of Arnim and Brentano was not discussed in Russia—at least in Russian journals there is no response either to that collection or to the “Spring Wreath” (Azadovsky, 1958: 316). Listing for N.M. Yazykov the collections of songs known to him in a letter, P.V. Kireevsky did not mention “The Boy’s Magic Horn” (Kireevsky I.V., Kireevsky P.V., 2006: 376–377). Probably, the parallel in behavior between the German and Russian collectors lies in typology. Obviously, the motives of Arnim and Yakushkin were different. The former wore simple clothes trying to get closer to his ideal of a national poet, while the latter did the same from a natural inclination and for the sake of simplifying the recording of songs.

The motif of changing clothes in Russian folklore

The cultural, historical, and literary circumstances described above, that is the attention of the Slavophiles and folk song collectors close to them to peasant clothing, might certainly have served as a breeding ground for the instructions of M.P. Pogodin. Yet, none of them can be considered to be its main source. Moreover, the proposal to go to villages under the guise of a peddler does not find any direct parallels in the history of the previous folklore studies at all. Most likely, this was Pogodin’s own idea. However, in this case he must have relied not so much on literary, but on folklore sources.

The “disguising”, of which the peasants accused Pavel Yakushkin, was well-known to them primarily from the calendar rituals of Christmastide and Cheese-fare Week. The dressing of a person belonging to a noble or even royal family in simple clothes was also a widespread subject of folklore*. In popular legends about kings and other dignitaries, this subject was used most frequently; as a rule, the changing of clothes was performed in such cases for getting closer to the people (Chistov, 1967: 207, 212).

M.P. Pogodin, a researcher and connoisseur of folk culture, collector and publisher of handwritten antiquities, author of novels in the popular style, insightfully suggested making the move captured in the saying, “Greet him according to his clothes, take leave according to what he knows” for communicating with peasants. And it seems that he turned out to be accurate in his calculations: Pavel Yakushkin followed his advice and became one of the most successful collectors and ethnographers. Certainly, the recipe for success was not limited to the outfit alone, but the clothes and carrying basket on his back indeed made a good impression on the villagers.

Although wearing a traditional outfit for Yakushkin was not an ideologically colored gesture—despite his inclination for provocative behavior, he nevertheless did not like play-acting, masquerading, or “buffoonery”. M.I. Pisarev, who described the last days of Yakushkin, cited his following words, “Eccentric characters are born, not made… I do not like buffoonery. Nothing can be more disgusting…” (Russian State Archive of Literature and Art. F. 236, Inv. 1, D. 367, fol. 2v).

Based upon the fact that in his instructions Pogodin offered the student Yakushkin to change into a traditional outfit and grow a beard, in his early years Yakushkin did not wear either of the two. Gradually, however, wearing plush pants and red shirt became an integral part of his existence; it had nothing to do with “disguise”. Judging by Yakushkin’s “Travel Letters”, informants from among the common people (peasants, their wives, retired soldiers, fishermen, or trade people) did not have a problem with his glasses, and saw not a “disguised landowner” in him, but a “traveling man”, calling him “dear”, “honorable”, “darling”, or “brother” (1986: 44, 122, 131, 252, 259).

Followers of Yakushkin

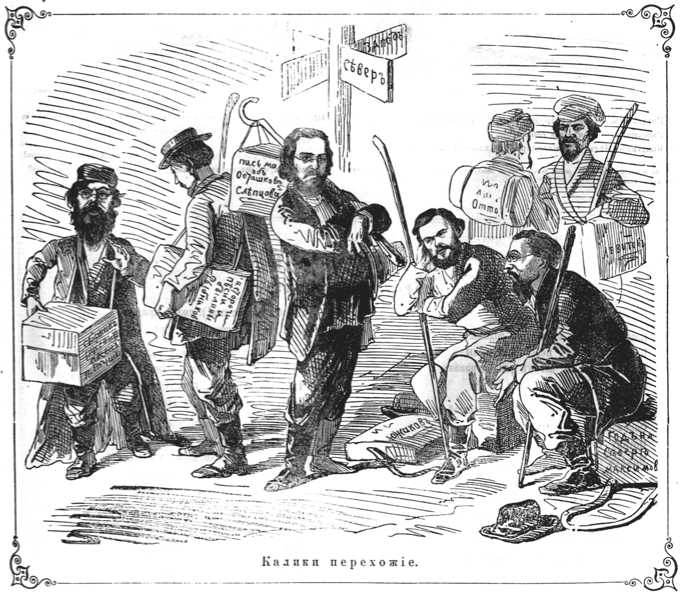

Very few of the ethnographers of the 1850s–1860s dared to use the “disguising” practiced by Yakushkin, primarily because it was risky—not everyone was ready to confront the authorities. The ethnographer and traveler S.V. Maksimov, a close acquaintance of Yakushkin and the author of his first biography, was one of his few and brief followers. He made his first expeditions (1855– 1858) walking around villages either wearing peasant clothes or the outfit of an ordinary merchant (Tokarev, 2015: 428; Lebedev, 1994: 486). P.N. Rybnikov also wore a traditional Russian outfit during his trip to the Chernigov Governorate, where he collected information on the history of local industry as well as folklore and ethnographic materials. Soon he was arrested “on suspicion of having relations with the schismatics and for inappropriate discussions about political matters” (Saprykina, 2007: 401), although there were rumors that one of the reasons was his traditional Russian outfit (Herzen, 1958: Vol. 14, 144). Rybnikov himself thus explained, “…I decided to leave the post road and drive along the governorate using village roads and by water. This gave me the means to look closer into the everyday life of peasants and it partly spared from officiality. It is known how difficult it is for a ‘landowner’ and especially for an official to get some accurate information from simple people. His title, his travelling document, the whole situation of his driving places somehow does not inspire people’s confidence in him; a peasant is always inclined to suspect that an official has, perhaps, some ‘pertinent’ business concerning him, and even if there is no pertinent business, the very person of the official, his concepts, his habits, make him a stranger to the peasant. Can it be true, some would say, in order to collect ethnographic data, one has to be dressed up in a traditional outfit and imitate the appearance of a commoner? Disguise and imitation, of course, are no good. But one can wear a traditional outfit, and then it is not without use for studying the life of the people in the regions of Great Russia. At least, this helped me personally in relations with the Chernigov Sloboda dwellers, although it entailed great inconveniences” (Rybnikov, 1864: X) (Fig. 4).

Obviously, over time there was no longer a need for ethnographers to change clothes: many of them began to travel to the far corners of Russian governorates as representatives of official expeditions organized by the Russian Geographical Society, the Academy of Sciences, and the Military and Maritime Ministries, and could use the advantages of administrative offices in their communication with peasants, also feeling protected from the local authorities. Pavel Yakushkin, who also became a corresponding member of the Russian Geographical Society, might probably have

Fig. 4 . “Kaliki perekhozhiye” (“wandering minstrels”)—members of ethnographic expeditions of the late 1850s to early 1860s. Caricature from the Iskra Journal (1864, No. 9). P.I. Yakushkin, P.N. Rybnikov, V.A. Sleptsov, I.I. Yuzhakov, and S.V. Maksimov are in the foreground; I.L. Otto and A.I. Levitov are in the background.

given up wearing a traditional outfit on expeditions, but the peasant short fur coat, boots, and red shirt had long become a part of his personality.

Conclusions

As it has been shown, Pavel Yakushkin’s dressing in a peasant outfit united two motives: a desire to designate his closeness to the popular environment through such external gestures, and the need to inspire trust in the common people. Subsequently, these two motives began to serve as the basis for two models of behavior actively used both by those who wanted to look like peasants out of sympathy for them and partly from ideological considerations, and those who wanted to make a good impression on them. When the Slavophiles would dress in traditional Russian clothes or A. Grigoriev with a guitar walked across all of Moscow to visit A. Fet, dressed in a “coachman’s outfit which did not exist among the simple people” (Fet, 1980: 331), we may say that they followed the first model. It turned out to be unusually viable, and in the early 20th century, M. Gorky (Skulptor…, 1964: 108) and “peasant poets” N. Klyuev, S. Gorodetsky, and in the early period S. Yesenin also emphasized their closeness to ordinary people by publicly wearing a traditional shirt with an off-center collar and high boots.

The second, “pragmatic” model, designed to win over people, was not widely used by ethnographers. However, it was actively used for other purposes far from gathering folklore. It was adopted by the Populists— young intellectuals who went to the working and peasant environment to propagate revolutionary ideas in the 1870s (in the framework of “going to the people”). In order to win over informants from among the simple people, they would also dress in peasant clothes and go to villages under the guise of trade middlemen and craftsmen. This is how the well-known anarchist P.V. Kropotkin described his “going to the people”: “Of course, all those who carried out propaganda among the workers, were dressed as peasants. The gap that separates the ‘landowner’ from the peasant in Russia is so deep, and they so rarely come into contact, that the appearance of a man dressed in a ‘lordly’ manner in a village would arouse everyone’s attention. But even in a city, the police would immediately be alerted if they noticed among the workers a person who differed from them in dress and speech. ‘Why would he hang around with ordinary people if he had no malicious intent?’ Very often after having lunch in an aristocratic house or even in the Winter Palace where I sometimes went to visit a friend, I would take a cab and hurry to my poor student’s apartment in the remote suburbs, where I took off my elegant clothes, put on a calico shirt, peasant’s boots, and fur coat, and went to my weaver friends, joking along the road with simple men” (Kropotkin, 1988: 307)*. As is known, despite the fact that peasants were quite eager to enter into conversation with propagandists, agitation of the Populists did not give any tangible results. Greeting them “according to his clothes”, the peasants still bid farewell to them “according to what he knows”.

In the 20th century, after the October 1917 Revolution, the distance separating “landowners” from peasants, common people from the intelligentsia, was reduced for obvious historical and political reasons. In a situation when the class borders turned out to be practically erased, there was no longer any need to change into peasant clothes for confidential conversation with the people. Thus, the second model which appeared thanks to M.P. Pogodin and was strengthened thanks to P.I. Yakushkin, died out after existing for over half a century. At the same time, the use of traditional outfits as a political and ideological gesture has survived until nowadays: recent political events in the Ukraine have sharply increased the demand for ethnic “embroidered shirts”, and Russians often wear traditional folk clothes during religious festivities, in particular church processions. Finally, in some regions, for example in Yakutia, the traditional folk costume can perform the function of the official representative clothing of the titular nation.