A diachronic study of negative imperatives in Mongolic languages

Автор: Su-ying Hsiao

Статья в выпуске: 4, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This paper investigates negative imperatives in Mongolic languages from a historical perspective. The distributions of negative imperative markers in Mongolic languages are compared, based on data drawn from corpora of texts from Middle to early Modern Mongolian, published field reports of Modern Mongolic languages, and our own field notes. Negative imperatives are mainly marked by a pre-verbal negator buu in Mongolian historical documents such as Secrete History of the Mongols, Altan Tobči, Erdeni-yin Tobčiya and Mongolian Laokida. In Modern Mongol proper, buu rarely appears and bitegei is used instead. However, buu is used in Dagur and several Mongol vernaculars spoken in Eastern Inner Mongolia, Liaoning and Heilongjiang, where contacts and inter-actions among Mongolian and Sinic people are lively and the Mongolian spoken in that area contains abundant Chinese borrowings. Santa and Mongghul-Mangghuer, two Mongolic language located far from Eastern Inner Mongolia also uses buu. It is argued that buu in modern Mongolic languages is not a Chinese loanword but a retention of Middle Mongol buu.

Negative imperative, prohibitive, Mongolic language, lexical borrowing, retention, innovation, conditional converb

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148315843

IDR: 148315843 | УДК: 811.512 | DOI: 10.18101/2305-459X-2020-4-8-22

Текст научной статьи A diachronic study of negative imperatives in Mongolic languages

Geographically, Mongolic languages are located in Mongolia, Republic of Buryatia, Republic of Kalmykia, Afghanistan, and Inner Mongolia, Laoning, Heilongjiang, Gansu, Qinghai, Xinjiang of China. Rybatzki [27, p. 388-389] tentatively classifies Mongolic languages into the following six subgroups according to their relevant phonological, morphosyntactic and lexical properties: (1) Northeastern Mongolic: Dagur; (2) Northern Mongolic: Khamnigan Mongol-Buryat; (3) Central Mongolic: Mongol proper-Ordos-Oirat;(4) South-Central Mongolic: Shira Yughur; (5) Southeastern Mongolic: Mongghul-Mangghuer-Bonan-Santa; and (6) Southwestern Mongolic: Moghol.

This paper investigates negative imperatives in Mongolic languages from a historical perspective. The distributions of negative imperative markers in Mongolic languages are compared, based on data drawn from corpora of texts from Middle to early Modern Mongolian, published field reports of Modern Mongolic languages, and our own field notes. Data of Modern Mongolic languages used in the paper include: (1) Dagur (1988); (2) Khamnigan Mongol, Buryat (Buryat, Bargut dialect); (3) Mongol proper (Dörbet, Kharchin, Khalkha varieties), Oirat; (4) Shira Yughur; (5) Mongghul-Mangghuer, Bonan, Santa, Kanjia. Unless noted, examples are drawn from my field notes. All glosses are mine. Diachronic data are retrieved from corpora of the following historical texts: Mongγol-un niγuča tobčiyan (1228) ‘Secret History of the Mongols’(SHM), Mongolian monuments in ‘Phags-pa script (1276-1368) (Tu-murtogoo 2010), and Pre-Classic Mongolian monuments in the Uighur-Mongolian script (13th-16th centuries) (Tumurtogoo 2006) for texts represented Middle Mongol (13th century to 16th century); Manju-i yargiyan kooli (1635) ‘Manchu Veritable Records’(MSL), Erdeni-yin Tobčiya (1662) ‘Precious Summary'(ET), Beijing woodblock version of Mongolian Geser (1716), Mongolian Laoqida (1790) (LQD), and Köke Sudur (1871) ‘The blue chronicle’(KS) for Late Mongol texts (17th century to 19th century); Manju monggo nikan ilan acangga šu-i tacibure hacin-i bithe (1909, 1910) ‘Manchu-Mongolian-Chinese Readers’ (MMC) for Early Modern Mongolian (early 20th century).

2. Negative Imperatives in modern Mongolic languages

Most of negative imperative markers in modern Mongolic languages correspond to Written Mongol buu and bitegei .

Dagur: /buː/

-

(1) ɡɑᶅeːr buː nɑːdtu, xɑl-ɣuitɑː. [14, p. 343]

|

"Don't play with fire! You may be burned." |

|

|

Khamnigan Mongol: buu (2)a. buu kele. |

[19, p. 98] |

|

NEG say.2IMP "Do not mention [it]!" b. buu martaarie. NEG forget.2OPT "[please] do not forget [it]!" Buryat: bü (3) bü yab-uuzha-b. |

[29, p.114] |

|

NEG go-DUB-1SG "I shall not go!" Bargut (a dialect of Buryat): /buː/ (4) ʃiː buː xəntəɡləːreː |

. [3, p. 235] |

|

you.NOM NEG be_angry.2OPT “Please don't be angry!” Dörbet (a dialect of Mongol proper): /buː/

NEG be_naughty.2IMP “Don't be naughty!” Kharchin (a dialect of Mongol proper): /buː/

NEG go.2IMP “Don’t go!” Mongghul-Mangghuer: /biː/

|

[10, p. 223] |

|

sound NEG come_out.2IMP "Don't make any sound!" (8) bu biː daulaja ba. |

[10, p. 224] |

|

1SG.NOMNEG sing.1VOL PTCL |

|

|

“Let me not sing!” (9) mahani bii ide |

[16, p. 303] |

|

meat NEG eat.2IMP |

|

“Do not eat [the] meat!”

It is noteworthy that irrealis negator /liː/ (< ülü) sometimes plays the role of negative imperative marker. See (10). On the other hand, (11) exhibits that /biː/, like /liː/, may occur in a conditional clause.

|

(10) te liː |

jaulaxɡɘ |

budaŋɢʊla |

jauja. |

|

3SG.NOM NEG go.3OPT [10, p.224] “Don’t let him go, we’ll go.” (11)a. ʨɘ biː |

1PL.NOM jausa |

go.1VOL amaxɡɘna? |

[10, p. 233] |

|

2SG.NOM NEG go. CVB "What if you don't go?" b. ʨɘ liː ɕiʥisa |

how.NPST te |

rɘguna. |

“If you don’t go, he will come.”

Besides, preverbal negators may occur before a “converb-imperative verb” chunk if the converb doesn’t take any argument, and are adjacent to the imperative verb if the converb takes arguments. Compare (12)a and (12)b,c.

(12)a. ʨɘ biː baɢala ɕiʥɘ. [10, p. 233]

“You don’t go to hit [someone/something]!”

-

b. maxanɘ idela liː ɕiʥim.

“I’ll not go to eat the meat.”

-

c. ʨɘ nara baudɘlaː biː sau.

“You don’t sit until the sun sets!”

-

(13) ce be er. [17, p. 343]

"You, do not come!"

Santa: /bu/

-

(14) bi xui ʥiərə bu kiəliəjə,

"I'll not say [anything] at the meeting! Let him not say [anything], too!"

-

(15) kieme-de bu kielie [24, p. 362]

who-DAT NEG say. 2IMP

"Do not tell anyone!"

BITEGEI forms are utilized in Khalkha dialect of Mongol proper, Spoken Oirat, Kanjia, Shira Yughur and Bonan.

Khalkha: /bitgi:/~/bitxi:/

-

(16) engeʤ bitxiː xel!

like_that NEG say.2IMP

"Don't say [things] like that!"

-

(17) bitgii gar. [31, p. 165]

NEG come_out.2IMP

"Don't go out!"

Spoken Oirat: / biʧɡᴂː/ ~ /biʧɡɑː/~ /biʧkɑi/

-

(18) Bidniːɡeː biʧɡɑː mɑrtɑː.

-

1PL.ACC NEG forget.2IMP

“Don’t forget us!”

-

(19) ʧinᴂmᴂːɡ biʧɡᴂː xɑrʃliːʧ, [11, p. 253]

NEG disturb.2OPT bi tʊŋ ɑdɢɑmtᴂː bᴂːnᴂːb.

“Please don’t disturb me now, I’m very busy.”

Birtalan [4, p. 226] notes that Spoken Oirat negative imperatives are bitkä~bicke~bicge~bice 'do not'.

Kalmuck, a dialect of Oirat, uses bicä .

Kalmuck: bicä

(20)a. bicä ir [5, p. 246]

NEG come.2IMP

"Don't come!"

-

b. bicä ir-tn.

NEG come-2OPT

"[Please] don't come!"

-

c. bicä ir-iy.

NEG COME-1VOL

"I will not come!"

-

d. bicä ir-txä

NEG come-3OPT

"[Let him] not come!"

In Kangjia and Shira Yughur, the forms büde~ püti are used as negative imperative marker, while /təgə/ occurs in Bonan negative imperatives.

Kangjia: büde

(21)a. ʧi küni büde sügü!

[28, p.203]

“Don’t curse anyone!”

-

b. tasɯ büde ʤaχara!

“Don’t be noisy.”

-

c. kɔmida la büde medeʁa!

“Don’t let anyone know (it)!”

Shira Yughur: /pʉtə/~ püti

(22)a. bu pʉtə hɑnəjɑ/hɑnəsɑː. [12, p. 247]

“I will not go.”

-

b. ʧə pʉtə hɑnə!

“Don’t go!”

-

c. munə kyken nɑɡtə pʉtə hɑnəɡɑne!

“I hope that my son will not go into the woods.”

-

(23) ci püti tamiki soro-soo. [26, p. 275]

"[Please ]do not smoke tobacco!"

Bonan (Bao'an): /təgə/~tege

-

(24) a. ʨi təgə ɢuara! [9, p. 204]

“Don’t be angry!”

-

b. ʨi təgə ɢuarase:.

“Please don’t be angry.”

-

(25) tege d angla [17, p. 343]

NEG stop.2IMP "Do not stop [them]!"

Like the case in Mongghul-Mangghuer, conditional clauses may contain optative meaning (polite request, wish...), and negators for indicatives/interrogatives may occur. But unlike Mongghul-Mangghuer, negative imperative marker does not appear in Bonan conditional clauses. Compare (24)b and (26). It shows that the Mongghul-Mangghuer conditional clauses at issue are treated as imperatives themselves, while the imperative meaning of their counterparts in Bonan are derived from the context. Also note that in (25), realis negator ese, not irrealis negator ülü, is used. It suggests that the construction involved is subjunctive.

-

(26) ʨi ese ɢuarasa/ɢuaragisa. [9, p. 204]

“Please don’t be angry.” (Literally, if you [were] not angry,...)

To sum up, BU forms occur in Dagur, Khamnigan Mongol, Buryat, Written Oirat, Mongghul-Mangghuer, Santa, sGo.dmar subdialect of Qinghai Bonan and Dörbet, Kharchin dialects of Mongol proper. BITEGEI forms appear in Khalkha dialect of Mongol proper, Spoken Oirat, Kanjia, Shira Yughur and Bonan. Besides, negators /liː/ (<ülü) and ese occur in conditional clauses with imperative meaning in Mongghul-Mangghuer and Bonan respectively.

BU is used in several Mongolian vernaculars, Bargut and Dagur spoken in Eastern Inner Mongolian, Liaoning and Heilongjiang, where contacts and interactions among Mongolian and Sinic people are lively and the Mongolian spoken in that area contains abundant Chinese borrowings (Bao 2006, our field notes). While BU is phonetically identical to Chinese negator bù ( 不 ), is BU in these modern languages/dialects recently borrowed from Chinese? The answer is No. First, BU appeared as early as in the 13th century. Second, Mongolic languages located far from Eastern Inner Mongolia such as Buryat, Santa, Written Oirat, and Mongghul-Mangghuer also use BU. Even though Santa and Mongghul-Mangghuer have intensive contacts with Chinese and it's not unlikely to borrow BU from Chinese independently, Buryat, which is spoken in Siberia, is rather free from Chinee influences. Therefore, BU is a retention from Proto-Mongolic.

Although Chinese bù ( 不 ) 'not' originally took a final stop, the final stop was lost in Guānhuà 'Mandarin'. It was listed in Mengguziyun 'Rhyme Book of Phagspa-Chinese characters' under the categories “bu”, “fu” and “fuw”. That is, Chinese bù ( 不 ) and Proto-Mongolic BU are phonetically identical. Is the Mongolian BU an ancient borrowing from Chinese bù , then? The answer is No, either. Chinese bù was barely used as an imperative negator when the Chinese version of Secret History of the Mongols was transcribed and translated in early Ming dynasty. The Chinese character 不 was used to transcribe the sound “bu” (including the negative morpheme and the syllable /bu/), but in most of the cases xiū ( 休 ) 'don't' was chosen as the gloss for Mongolian negative jussive bü .

Among 71 tokens of the negator bü , only two were glossed as 不 . See (27).

“I will not make its linchpin to overturn the cart with a lock.”

It is unlikely that Chinese bù ( 不 ) was borrowed into Proto-Mongolic and played a role it rarely played at that time.

3. Negative Imperatives in Mongolian Historical Texts3.1 Negative Imperatives in Middle Mongolian Texts

There appear 71 tokens of the negator bü in Secret History of the Mongols. Bü cooccurs with 1st, 2nd, 3th person imperatives/optatives/jussives. See (28)-(30) 1 . Bü appears before the verbs in imperative form or the verbal chunk. See (29)a, b.

(28)a. bida bü bawu:ya ! [SHM S118_V03_31b_2]

“We will not stay!”

-

b. manaγar-un unda:n bü meküde'ü:lsügei ! [SHM S124_V03_45a_4]

“I will not let morning drinks insufficient.”

(29)a. quda kö'ü: minü noqai-yača bü

“Quda, don’t cause my son to be scared by the dog.”

-

b. ta ber bü a(b)ču yabudqun !

[SHM S72_V02_03a_3]

“You don't take [us] away, too”

-

(30) bidan-u beye čerig ese γaru'a:su bidan-ača

separately other nightguardsoldier NEG come_out.3JUS

[SHM S278_V12_40a_2]

“If our personal soldiers do not go out, let other nightguards separately from us not go out!”

There are 5 tokens of the form bütügei in Secret History of the Mongols. One of them is the 3rd imperative form of the verb “to be”. See (31).

-

(31) ‘añgida qolo buyu.’ bütügei ! [SHM S189_V07_11b_5]

“Let [them] be far away [from us] separately!”

The other 4 tokens of bütügei are negative imperatives. Different from negative imperative marker bitegei in modern languages, bütügei in SHM are main verbs. Its meaning is “abstain, refrain”.

-

(32) aqa de'ü:-dür sayi iǰilidülčen

(33)…erte early eye harmony

Alan eke-yin

Alan mother-GEN

üge

'ü:n büi ?

ya:kin why

[SHM S76_V02_08b_1:2]

-

(34) qan ! qan ! bütügei ! [SHM S174_V06_16b_2]

king king abstain.3JUS

“Qan, Qan! Abstrain [from rush to fight against Temüjin]!” 1

-

(35) ese uqaγsan-dur bütügei ! [SHM S242 V10_24a_4:5]

-

205 tokens and 86 tokens of bü occur in Mongolian monuments in ‘Phags-pa script (1276–1368) and Pre-Classic Mongolian monuments in the Uighur-Mongolian script (13th–16th centuries) respectively.

(36)a. ėden-u gŭen-dür gėyid-dur 'anu

ėlč'in bu ba·ut'uq'ayi ! [THE EDICT OF MANGAL (1276)]

messager NEG lodge.3JUS

"Let messagers not lodge at their temple and houses!"

"Let [them] not take their lands, water right and whatever by force!"

|

c. ėde basa sėnšhiŋud |

bič'igt'en g·eǰu yosu 'üge·uė |

|

'üėles bu behavior NEG |

'üėledt'ugeė ! do.3JUS |

"Let them not, saying that they are Taoist monks with [the prince's] edict, do ruleless behabiors, either!"

Like the cases in Mongghul-Mangghuer, BU is adjacent to the imperative verb if the converb takes arguments. See (36)b above.

The frequency of negative imperative markers in some Middle Mongolian documents is summarized as Table 1.

Table 1

Tokens of imperative negators in Middle Mongolian historical documents

|

Sources Negators |

Secret History of the Mongols (1228) |

Mongolian monuments in ‘Phags-pa script (1276–1368) |

Pre-Classic Mongolian monuments in the Uighur-Mongolian script (13th–16th centuries) |

Sum |

|

Bü |

71 |

205 |

86 |

362 |

|

Bütügei |

4 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

3.2 Negative Imperatives in Late Mongolian Texts

The frequency of negative imperative markers in some Late Mongolian documents is shown in Table 2. bütügei disappeared in these Late Mongolian Texts, while bitegei emerged.

Table 2

Tokens of imperative negators in Late Mongolian historical documents

|

Sources Negators |

Manju-i yargi-yan kooli (1635) |

Erdeni-yin Tobčiya (1662) |

Beijing Geser (1716) |

Mongolian Laoqida (1790) |

Köke Sudur (1871) |

Sum |

|

Buu |

65 |

17 |

69 |

29 |

57 |

237 |

|

Bitegei |

0 |

0 |

4 |

7 |

116 |

127 |

Neither Manju-i yargiyan kooli nor Erdeni-yin Tobčiya contains bütügei/bitegei . Besides of 2nd person imperative, buu occurs with 3rd and 1st person imperatives.

-

(37) ‘namayi buu alatuγai!’ kemen ayuǰu es_e

ügülelüge . [MSL V2_91a_6:7]

"[I was] scared of being killed and didn't say [who I am]."

-

(38) činü ǰarliγ-ača buu dabay_a ! [ET V1_3r_26]

"Let's not violate your edict!"

The innovative form bitegei emerged in 18th century's Beijing Geser and Mongolian Laoqida, and occurs more frequent than buu in Late 19th century's novel Köke Sudur.

“Well, if you say such bad words, don’t catch up with me tomorrow!”

-

b. ta balai bitegei sayirq_a [Geser V1_39b_11]

"You don't boast stupid words!"

Note that bitegei can appear without taking an overt imperative verb in Beijing Geser, reminiscent of bütügei in SHM. See (40).

-

(40) abai bitegei ai . [Geser V4_6b_22:23]

baby NEG PTCL

"Baby, don't [do it]!"

It's surprising that bitegei may appear in an indicative clause. See (41).

-

(41) eǰei minu bitegei dügürčü [Geser V1_46b_13]

ükünem bayinam.

"My mother, don't [eat too much and] become stuffed!"

buu in Geser also shows interesting behavior. It may appear before an object-verb chunk. See (42)b. In (42)c, the verbal phrase "am kürge" was written as one word. (42)a. eǰei minu buu qariy_a ! [Geser V1_10b_12]

“My mother, don’t curse!”

-

b. nigen nigen-d'egen buu amu kürgelčey_e !

[Geser V1_20a_8:9]

"Let's not send even one bite into [one's] mouth!"

-

c. miqan-i nada buu amkürge ! [Geser V1_19b_6]

"Dont send meat to my mouth!"

buu and bitegei are competing forms, which occur in the same contexts. Compare (43)a, b.

(43)a. či erte buu eči ! [LQD V2_10a_4]

"You don't do early!"

-

b. ger-ün eǰen tür

bitegei eči ! [LQD V2_25a_2] go.2IMP

house-GEN master temperary NEG “Host, don’t leave at this moment!”

Negative imperative markers can occur before a verbal chunk, such as "Converb-MainVerb", "Verbl_Noun-AuxVerb" and "Complement-AuxVerb". See (44)a, b, c. Note that (44)c contains a lengthy complement composed of two phrases, i.e. "či mau bi sayin geǰu" and "nür ügei", and buu occurs between them.

(44)a. či sayitur idegülǰü ongγuča-du buu

"You nicely feed [the horses] and don't fill the receptacle!"

-

b. öndürken qarbuγad buu kürgekügei bolqu , boγoni

"Shoot rather high and do not become undelivered. When shooting low the arrow goes shaky."

-

c. bida nökürleǰu yabuqula či mau bi

-

3.3 Negative Imperatives in Early Modern Mongolian Texts

There are 40 tokens of buu and one case of bitegei in Manju monggo nikan ilan acangga šu-i tacibure hacin-i bithe (1909, 1910). buu appears before the verbal phrase. (45)a. baγsi namayi surγaγad , ” ene üge-yi buu

"When we make friends, don't say "You're bad. I'm good." and make [your friend] faceless."

mouse-ACC hit.2OPT

"Forbiding small boy servant, 'don't hit mouses!' "

-

c. buu modun-u dour_a niγuγtun ! [MMC 7T_228_5]

NEG tree-GEN under hide.2OPT

"Don't hide under a tree!"

The only case of bitegei in MMC is used as a main verb, too. See (46).

“Don’t make (them) too thirsty!”

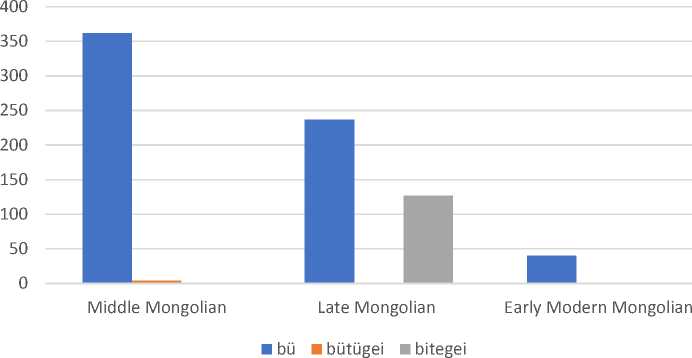

The use of buu declines from Middle Mongolian to Modern Mongolian. See Figure 1.

Tokens of bü (buu), bütügei and bitegei

Figure 1. Numbers of tokens of bü, bütügei and bitegei in three periods buu was replaced by bitegei in some languages/dialects/varieties but resists in others. There are 4 tokens of negative bütügei in SHM. The form bitegei appears in mid-17 century and is abundant in late 19 century. Nowadays, BU forms occur in Dagur, Khamnigan Mongol, Buryat, Written Oirat, Mongghul-Mangghuer, Santa, sGo.dmar subdialect of Qinghai Bonan and Dörbet, Kharchin dialects of Mongol proper. BITEGEI forms appear in Khalkha dialect of Mongol proper, Spoken Oirat, Kanjia, Shira Yughur and Bonan. Besides, negators /liː/ (<ülü) and ese occur in conditional clauses with imperative meaning in Mongghul-Mangghuer and Bonan respectively.

( bü atuγai >*bü ätügei > bütügei) . This analysis can account for the negative meaning easily, but the issue why a 3rd jussive form also occurs in 1st and 2nd person imperatives remains.

As for the etymology of bitegei , one possibility is that bitegei is a direct descendant of bütügei. bütügei becomes bitegei through de-rounding of the vowel /ü/. De-rounding of /u/~/ü/ is an abundant process in Mongolian. For example, bui 'to be' is pronounced as /bi ː/ in spoken language. Another possibility is that bitegei is not a descendant of bütügei, but a contraction of bü ‘NEG’ + tege- ‘to do so, thus, or that way’+ -ye ‘1VOL’ ( bü tegeye > * bütegei > bitegei ).

4.3 Concluding Remarks

We have traced the development of BU and BITEGEI from Middle Mongolian to Modern Mongolic languages/dialects. We find that realis and irrealis negator ese and ülü may be interpreted as negative imperative marker in some languages. Primary results show that it might be related to conditional/subjunctive. We also proposed tentative analyses for the etymology of bitegei and bütügei . However, there remains missing links of empirical data and problems unsolved. We'll leave them for further research.

Abbreviations

-

1, first person; 2, second person; 3, third person; ABL, ablative; ACC, accusative; CAUS, causative; COM, comitative; COOP, cooperative; CVB, converb; DAT, dative; DUB, dubious; FUT, future; GEN, genitive; IMP, imperative; INS, instrumental; IPFV, imperfective; JUS, jussive; LOC, locative; NEG, negation, negative; NOM, nominative; NPST, non-past; PFV, perfective; PL, plural; POSS, possessive; PST, past; PTCL, particle; REFL, reflexive; SG, singular; QUOT, quotative.

Список литературы A diachronic study of negative imperatives in Mongolic languages

- Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. «Imperatives and Commands», Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Bao, Lianqun. «Meng Han shuangyu xingrongci: qi gouci tezheng», (Mongolian-Chinese bilingual adjectives- its morphological features) paper posted at the 14th Annual Conference of the International Association of Chinese Linguistics & 10th International Symposium on Chinese Languages and Linguistics Joint Meeting, Academia Sinica, Taipei, May 25–29, 2006.

- Baoxiang & Jirannige, B. «Ba'erhu tuyu» (Bargut Variety), Hohhot: Inner Mongolia University Press, 1995.

- Birtalan, Ágnes. «Oirat», In Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 210-228. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Bläsing, Uwe. «Kalmuck», In Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 229-247. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Buhe. «Dongxiangyu he Mengguyu» (Santa language and Mongolian language), Hoh-hot: Neimenggu Renmin Publisher, 1986.

- Buhe & Liu Zhaoxiong. «Baoanyu Jianzhi» (Notes on Bao'an language), Beijing: Minzu Publisher, 1982.

- Buhe et al. eds. «Dongxiang Huayu Cailiao» (Santa Spoken Texts), Hohhot: Neimenggu Renmin Publisher, 1986.

- Chen, Naixiong. «Bao'anyu he Mengguyu» (Bao'an language and Mongolian lan-guage), Hohhot: Neimenggu Renmin Publisher, 1987.

- Chinggeltai et al. eds. «Tuzuyu he Mengguyu» (Mangghuer language and Mongolian language), Hohhot: Neimenggu Renmin Publisher, 1988.

- Choijongjab et al. eds. «Weilate fangyan huayu cailiao» (Oirat Dialect Spoken Texts), Hohhot: Neimenggu Renmin Publisher, 1986.

- Chuluu, B. & Jalsan. «Dongbu Yuguyu he Mengguyu» (Shira Yughur language and Mongolian language), Hohhot: Neimenggu Renmin Publisher, 1990.

- Cleaves, F. W. «The Secret History of the Mongols: Translation», Harvard-Yenching Institute, 1982.

- Enkhbatu. «Dawoeryu he Mengguyu» (Dagur language and Mongolian language), Hohhot: Neimenggu Renmin Publisher, 1988.

- Georg, Stefan. «Ordos», In Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 193–209. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003a.

- Georg, Stefan. «Mongghul», In Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 286–306. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003b.

- Hugjiltu, W. «Bonan», In Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 325–345. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003a.

- Injannasi. «Köke Sudur», 1871. Chifeng: Neimenggu Kexue Jishu Publisher, 2004.

- Janhunen, Juha. «Khamnigan Mongol», In Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 83–101. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003a.

- Janhunen, Juha. «Mongol Dialects», In Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 177–192. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003b.

- Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Junast. «Tuzuyu Jianzhi» (Notes on Mongghul), Beijing: Minzu Publisher, 1981a.

- Junast. «Dongbu Yuguyu Jianzhi» (Notes on Shira Yughur), Beijing: Minzu Publisher, 1981b.

- Kim, Stephen S. «Santa», In Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 346–363. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Liu, Zhaoxiong. «Dongxiangyu Jianzhi» (Notes on Santa), Beijing: Minzu Publisher, 1981.

- Nugteren, Hans. «Shira Yughur», In Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 265–285. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Rybatzki, Volker. «Intra-Mongolic taxonomy», In Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 364–390. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Sechenchogtu. «Kanjiayu» (Kanjia language), Shanghai: Yuandong Publisher, 1999.

- Skribnik, Elena. «Buryat», in Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 102–128. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Slater, Keith W. «Mangghuer», in Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 307–324. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Svantesson, Jan-Olof. «Khalkha», in Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 154–176. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Tsumagari, Toshiro. «Dagur», in Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 129–153. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Tumurtogoo, D. «Mongolian Monuments in Uighuric-Mongolian Script (XIII–XVI Centuries): Introduction, Transcription and Bibliography». Taipei: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, 2006.

- Tumurtogoo, D. «Mongolian Monuments in ’Phags-pa Script: Introduction, Transcription and Bibliography». Taipei: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, 2010.

- Weier, Michael. «Moghol,» in Janhunen, Juha (ed). «The Mongolic Languages», 248–264. Routledge Language Family Series 5. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Wulan. «Menggu Yuanliu Yanjiu» (Studies on Erdeni-yin Tobčiya), Shenyang: Liaoning Minzu Publisher, 2000.