A organization of a cooperative educational environment for students of the Japanese language using the example of work on essays

Автор: Marfina V.E.

Журнал: Высшее образование сегодня @hetoday

Рубрика: Трибуна молодого ученого

Статья в выпуске: 2, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Cultural differences in approaches to writing essays by native Japanese speakers are considered. The need to focus on the reader when writing essays in Japanese has been revealed. As a method of developing this skill, the use of the Digipad online corporate environment for student collaboration is proposed. Feedback from students about the degree of convenience and efficiency of working in this environment was analyzed.

Higher education, japanese language teaching, cooperative educational environment, writing as a productive type of speech activity

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148328809

IDR: 148328809 | УДК: 372.881.1 | DOI: 10.18137/RNU.HET.24.02.P.116

Текст научной статьи A organization of a cooperative educational environment for students of the Japanese language using the example of work on essays

Марфина В.Е.,

Российский университет дружбы народов

Организация кооперативной образовательной среды для изучающих японский язык на примере работы над сочинениями

Российский университет дружбы народов

Besides the obvious peculiarities of the Japanese writing system such as two syllabaries (hiragana and katakana), more than 2000 hieroglyphs and a sentence structure unusual for Russian learners, Japanese has a unique narrative style, which is frequently brought up by Japanese methodologists in their manuals, and which teachers should take into account when instructing students on writing.

As is stated in the article “Evaluation of “3P” writing approaches to the teaching of Japanese research paper writing” by Tsunehisa Tanaka, Japanese writing style originated from zuihitsu (“following the brush”, a form of essay) which can be characterized by its bad correlation with linear logic, strict rules and regulations required in Western reports. For Japanese people, writing is viewed as something spontaneous rather than arti- ficially constructed, subtext, vagueness and implications are valued more than openness and putting thoughts in a logical order. Instead of liner logic Japanese texts are based on circular reasoning, associations, changes of the topic and do not mind logical leaps and gaps [3, p. 158]. The author acknowledges that these features can lead to difficulties and misunderstandings in situations of intercultural communication, so he advises Japanese to adapt to English norms of narrative style when writing [3, p. 159]. It is worth noting that now one can easily find textbooks for Japanese university students aimed at teaching ro-jikaru raitingu (logical writing), which helps to bridge a gap between cultures. Meanwhile, there is no denying that when communicating with Japanese people, Japanese learners should take into account differences in cultural norms and writing styles.

Another aspect that deserves attention when writing a text in Japanese and teaching it to students is yomite ishiki (reader's awareness, or audience awareness), frequently referred to by Japanese methodologists. According to the definition by Hideyuki Sakihama, yomite ishiki is an ability to write and choose expressions based on information about the reader, or an ability to accurately grasp reader's knowledge to change the explanation to suit the reader [4, p. 207]. The need to focus on the reader is considered

ОРГАНИЗАЦИЯ КООПЕРАТИВНОЙ ОБРАЗОВАТЕЛЬНОЙ СРЕДЫ ДЛЯ ИЗУЧАЮЩИХ ЯПОНСКИЙ ЯЗЫК НА ПРИМЕРЕ РАБОТЫ НАД СОЧИНЕНИЯМ

МАРФИНА ВИКТОРИЯ ЕВГЕНЬЕВНА

Российская Федерация, Москва

VICTORIA E. MARFINA

Moscow, Russian Federation

necessary in writing by many Japanese researchers and methodologists. Midori Yoshida points out that audience awareness is introduced in native Japanese materials early on, as it can be seen implemented in the assignments from elementary school textbooks for Japanese children, where they are asked to write a letter or an explanatory text to their friend or a family member. It turns writing from being merely a practical task into a communicative activity, plus by imagining your reader it makes writing easier as one can write as if they are talking to their reader [5, p. 24].

Yomite ishiki appears as one of the requirements in Japanese Language Studies Course Guidelines for school pupils. For example, the instructions prescribe Japanese 3–4-year students to decide what to write about based on their interests and search for the appropriate content taking into consideration the objective of the writing and their reader. 8th grade students are required to reread a written text, paying attention to the use of words and sentences, the relationship between paragraphs, to make the text easy to read and understand [7, p. 109].

While on the subject of developing audience awareness, Reiko Ikeda writes about pluses of conducting exchange of compositions between university students and making them share their pair feedback, noting that such exchange makes learners see their text through the lens of their reader and consider who they are writing the text to and how they can write better [6, p. 105].

That position is broadly shared by the authors of the Japanese Foundation manual on teaching writing in Japanese to foreign learners “Kaku Koto wo Oshieru”. They also mention audience awareness as an important aspect in teaching writing, and to develop this skill, they similarly suggest that students work together in the classroom by discussing compositions and asking questions [8, p. 28–32]. This can be a good method, though, taking into consid- eration reduction of auditory hours, an emphasis on the student's independent work and a significant time consumption of composition writing, it seems reasonable to organize this type of work during students' extracurricular time. By creating an online cooperative educational environment for students to share and discuss their works and outlining the necessary amount of investment from each student, a teacher can solve a problem with students' lack of confidence in the classroom, when insecure students shy away from speaking and participating in the task. In addition, online environment lets a teacher observe all interactions between students since everything is recorded, so they can help or correct mistakes when necessary.

To evaluate the effectiveness of this approach, a pedagogical experiment was conducted from September till the end of December 2023 among beginner groups of Japanese language learners. The experiment involved 2 groups of A1 level students from the School of Young Philologist at Moscow State University and 2 groups of the 2nd year of the RUDN University with level A2.

First, students took part in a questionnaire to find out to what extend they pay attention to the audience awareness when writing a composition. Interestingly enough, the majority of students stated that they do take of consideration their reader in one the questions, but in a multiple-choice question that went right after that, where students were asked what aspects of the writing they consider important, only half of the students chose that they try to make their text easy to read and understand. This inconsistency in the answers made it doubtful that students were in fact paying attention to the audience awareness. Therefore, it was decided to organize an educational cooperative environment for two groups of each level and, at the end of the experiment, compare their results in writing compositions with the results of the other two control groups.

For an online space for students the choice was between 3 educational systems, namely Padlet, Digipad and SpacesEdu, all of which had comparable functionality. Though initially the experiment was conducted on the system Padlet, since it had already been tested earlier in a similar experiment with other groups, starting the end of October there were technical difficulties when working in the system, it was decided to switch to the Digipad system due to its very close resemblance to the previous environment to which students had already got used.

The sequence of tasks in Digipad generally corresponds to the one described in the article “Use of Information Technologies to Improve Productive Skills of the Japanese Language Students”, although it has been expanded for this experiment [1, p. 83– 84]. Precisely, this time in addition to the example of the text written by the teacher on the topic of the composition and video instructions uploaded on Youtube, students received tasks for preparatory work. Each task included vocabulary, reading and listening exercises. Students were asked to do the exercises, listen to the podcast in Japanese for the listening part, which they latter discussed in class with the groupmates, and prepare a draft of their composition to first share with the teacher via corporative mail. The teacher then provides feedback by recording a video response where they read the received text for a student to copy the pronunciation, to evaluate the natural- ness and smoothness of the text, and where explain student's mistakes. This part acts as the first step for a student to heighten their audience awareness.

Although introducing students to various technologies that can be useful when writing a text was not the main goal of the experiment, this process took place naturally thanks to video feedback technology. With the help of screen capture technology, a teacher can pay enough attention to the discussion of both student's language and contextual mistakes, demonstrate examples of suitable words from an electronic dictionary, provide an example of the proper pronunciation of individual words by recording them through a microphone, find an example of the correct spelling of a hieroglyph in a search engine [2, p. 259]. Some students noted that though at first they felt ashamed to watch a video explanation of their mistakes, later they got used to it and found it very valuable due to its repeatability.

After correcting the mistakes students uploaded their texts to Digipad and started the second phase of the work where they cooperated with each other by sharing feedback, questions and comments on each other's work in order to heighten their audience awareness. Digipad lets also

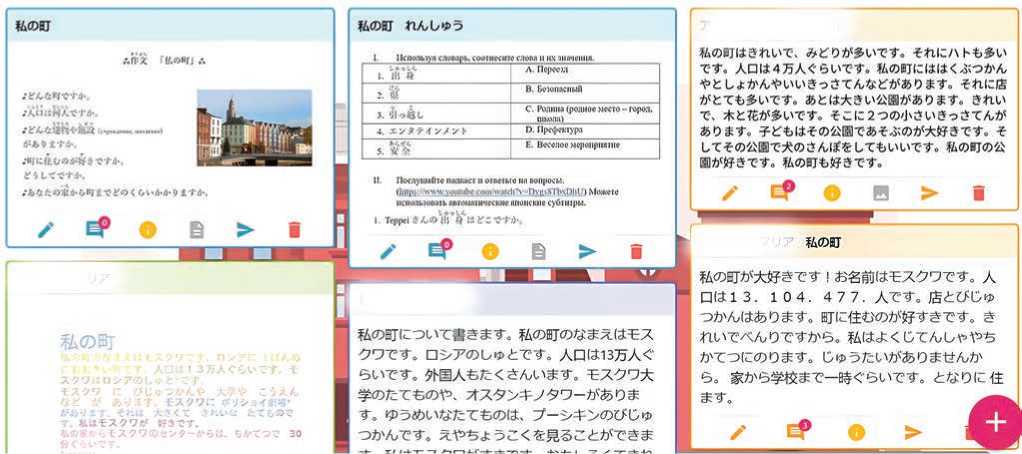

F igure. Digipad page with teacher's materials and students' compositions and comments*

* Origin:

ОРГАНИЗАЦИЯ КООПЕРАТИВНОЙ ОБРАЗОВАТЕЛЬНОЙ СРЕДЫ ДЛЯ ИЗУЧАЮЩИХ ЯПОНСКИЙ ЯЗЫК НА ПРИМЕРЕ РАБОТЫ НАД СОЧИНЕНИЯМ make audio recordings,so the last task was to make a recording with the retelling of the composition and the answers to other groupmates questions.

Later the participants shared in the questionnaire, that for some of them this format of work became a turning point and helped to revive their interest in learningJapanese. According to students' responses, it was interesting to read each other's texts, to train both speaking and writing and to support each other in the comments. They said that they would like to continue working with Padlet and

Digipad, as it helps to build a system from the knowledge that is taught in class, to hear the insights from their groupmates and to learn more about each other (Figure).

Although only 2 groups out of 4 were chosen to take part in the experiment, all students wrote the final composition of the semester to draw a conclusion and compare the results. In total, the participants of the experimental groups showed significantly better results and on average made 3 times less mistakes than students from the control groups. From these data the conclusion can be made that it is advisable to implement this system in the future. On the part of the teacher, it may take time to select interesting communicative topics, record video explanations and design exercises, but given the positive feedback from the students, the increase in the quality of their compositions and the reusability of the prepared materials with other groups of the same level,one can verify the operability of the proposed system.

Список литературы A organization of a cooperative educational environment for students of the Japanese language using the example of work on essays

- Марфина В.Е. Применение информационных технологий для развития продуктивных навыков обучающихся при обучении японскому языку // Высшее образование сегодня. 2023. № 5. С. 81-85. EDN: QQBHKP

- Марфина В.Е. Использование видео-обратной связи при проверке сочинений изучающих японский язык на начальном уровне // Современные проблемы филологии и методики преподавания языков: вопросы теории и практики: сборник материалов VII Международной научно-практической конференции, Елабуга, 20-21 октября 2023 г. Елабуга, 2023. С. 257-260. EDN: MRFUMY

- 田中恒寿. 日本語作文教育に応用した「3Pライティング」とその評価. 札幌大学総合論叢.2002.

- Цунэхиса Танака. Оценка подхода "3P writing" применительно к обучению японскому письму // Вестник комплексных исследований Университета Саппоро. 2002. № 13. С. 157-181. (на японском языке).

- 崎濱秀幸. 読み手に関する情報の違いが文章産出プロセスや産出章産.名古屋大学大学院教育発達科学研究科大学院研究生. 2003.

- Хидэюки Сакихама. Влияние различий в информации о читателе на написание текста // Бюллетень Высшей школы образования и человеческого развития Университета Нагои. Психология и науки о человеческом развитии. 2003. № 50. С. 207-212. (на японском языке).

- 吉田美登利.日本語作文の読み手意識についてー中国人学習者と日本人大学生の場合. 学習院大学人文科学論集2004.

- Мидори Ёсида. Об ориентации на читателя при написании сочинения на японском языке на примере японских и китайских студентов // Вестник Университета Гакуин по гуманитарным и естественнонаучным наукам. Токио. 2004. № 13. С. 23-47. (на японском языке).

- 池田玲子, 岡崎眸, 岡崎敏雄. 中上級を対象とする作文指導の方法. 日本語教育における学習の分析とデザイン.言語学習得過程の視点から見た日本語教育. 凡人社. 2002.

- Рэйко Икэда, Хитоми Оказаки, Тосио Оказаки. Метод обучения написанию сочинений на пороговом продвинутом уровне. Обучение японскому языку с точки зрения процесса овладения языком. Токио: Бонинся, 2002. 191 с. (на японском языке).

- 岸学、辻義人、籾山香奈子. 説明文産出における「読み手意識尺度」の作成と妥当性の検討.東京学芸大紀要 総合教育科学系.2014.

- Манабу Киши, Есихиро Цудзи, Канако Момияма. Разработка и апробация шкалы ориентации на читателя при написании сочинений // Вестник Департамента образования и науки Токийского университета Гакугэй. 2014. № 65. С. 109-117. (на японском языке).

- 書くことを教える (国際交流基金日本語教授法シリーズ). ひつじ書房.2010.

- Обучение письму. Серия по обучению японскому языку от Японского фонда. Токио: Хицузи Сёбо, 2010. 124 с. (на японском языке).