An Unexpected Epigraphic Find in the Athonite Monastery of Vatopedi and Its Comparative Study

Автор: Liakos D.

Журнал: Вестник ВолГУ. Серия: История. Регионоведение. Международные отношения @hfrir-jvolsu

Рубрика: Византийская церковь

Статья в выпуске: 6 т.30, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The author focuses upon an inscription revealed in the circular baseline of the dome in the Catholicon (the cathedral church) of the monastery of Vatopedi at Mount Athos. Athanasius, who is mentioned in the inscription, can be identified with the abbot Athanasius recorded in the documents from 1020 until 1048. This recently uncovered dedicatory inscription and the similar in structure inscription on the pavement of the Catholicon of the monastery of Iviron are important examples promoting church officials in donation or renovation of the Catholicons in the flourishing Athos during the eleventh century. Through targeted expressions containing the quotations of psalms, the patron’s images are constructed, and their reputation after their death is strengthened. The discovery of the inscription is extremely important, the evidence undoubtedly shedding light on the early architectural history of the Catholicon. The latter has been thoroughly documented, but its study continues to be of interest to researchers until today.

Mount Athos, monastery of Vatopedi, Athanasius, St Athanasius the Athonite, Catholicon, dome, opus sectile, monastery of Iviron

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149150176

IDR: 149150176 | УДК: 930.271(100):726.7 | DOI: 10.15688/jvolsu4.2025.6.11

Текст научной статьи An Unexpected Epigraphic Find in the Athonite Monastery of Vatopedi and Its Comparative Study

DOI:

Цитирование. Льякос Д. Неожиданная эпиграфическая находка в Афонском Ватопедском монастыре и ее сравнительное изучение // Вестник Волгоградского государственного университета. Серия 4, История. Регионоведение. Международные отношения. – 2025. – Т. 30, № 6. – С. 150–162. – [На англ. яз.]. – DOI:

Introduction. Until recently Athonite epigraphy had received very little attention from scholarship [12, pp. 279-282]. Although the fundamental corpus of the pioneer Byzantinists G. Millet, J. Pargoire, and L. Petit [15] appeared at a very early stage of Athonite studies, knowledge of the Byzantine and post-Byzantine Athonite inscriptions had been minimal and not on secure footing. Just recent years have witnessed a veritable surge of interest in Byzantine and postByzantine inscriptions of Mt. Athos. Following the first contribution of G. Millet, J. Pargoire, and L. Petit, some scholars did attempt to approach the subject, either dealing with already published inscriptions or presenting unknown material 2. In my recent papers I studied in detail the role and function of some Byzantine and early postByzantine dedicatory inscriptions on Athos, through the selection of unknown items and the reconsideration of published material [12; 8; 10]. In a very recent essay, two well-known dedicatory inscriptions from the monasteries of Megiste Lavra and Vatopedi were re-examined in depth [21, pp. 128-140].

The middle Byzantine dedicatory inscriptions on Mt. Athos. Research on the Byzantine dedicatory inscriptions in Mt. Athos has to deal with the reality of a lack of material. Due to irretrievable losses of buildings and artifacts as well, the number of Byzantine dedicatory inscriptions is extremely scarce. So, little is known about patronage activity in the Byzantine era, due to the paucity of epigraphic material concerning the building history of almost all monasteries. It is noteworthy indeed, with regard to what is known about patrons, that in all cases our knowledge is boosted by documents. The few Byzantine dedicatory inscriptions are of particular interest for the study of Athonite patronage; the most important ones are the patron’s invocation in the door lintel of the Catholicon (cathedral church) of the old monastery (nowadays cell) of Trochalas [12, pp. 284-285], the epigram composed for the bell tower and the phiale 3 in Lavra [8, p. 161; 21, pp. 128-140], and the inscription of the Catholicon of Pantocrator [8, pp. 160-161].

The emergence of coenobitic monasticism after the foundation of Lavra was to take on wider dimensions during the eleventh century through activities linked directly with donations and patronage of emperors and upper-class persons [11; 10]. However, the Middle Byzantine epigraphic testimonies from Mt. Athos are too few, and they are not commensurate with the growing increase in patronage and building development of the monastic complexes at the time Mount Athos experienced prosperity with the foundation of numerous monasteries, especially in the eleventh century.

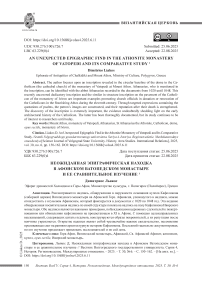

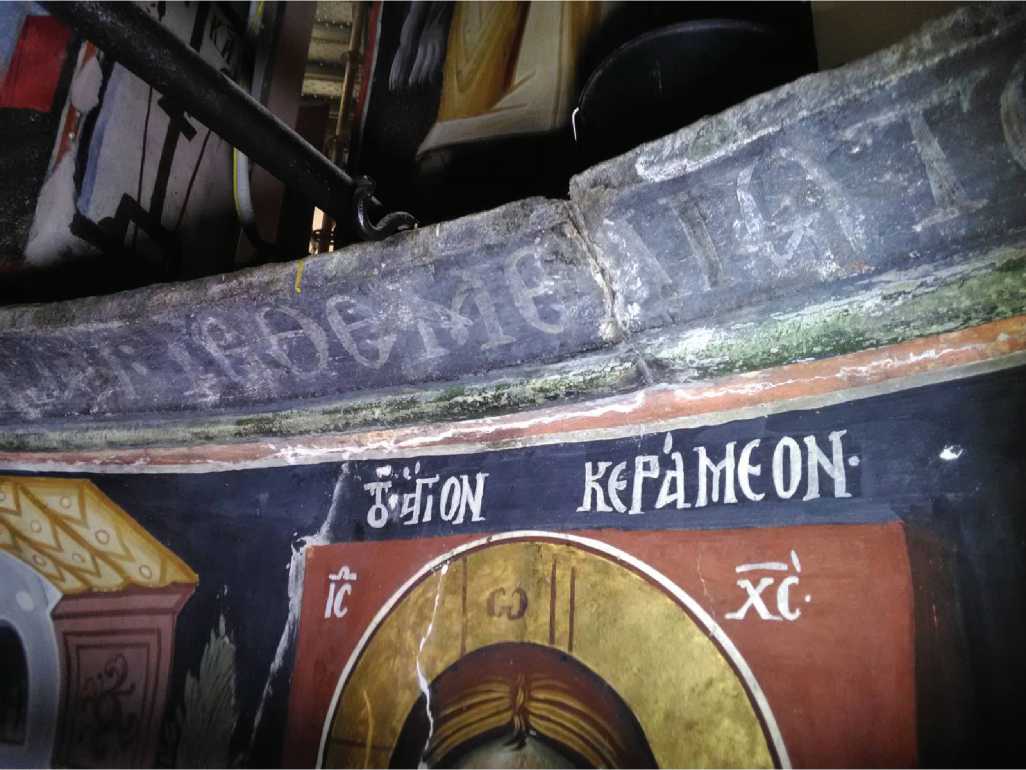

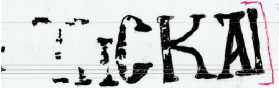

The revealed dedicatory inscription in the monastery of Vatopedi. This paper focuses upon the evidence of an inscription revealed in the circular baseline of the dome in the Catholicon of the monastery of Vatopedi (Fig. 1); recent conservation works on the frescoes of the Catholicon brought to light many significant elements for its painted decoration. Earlier frescoes’ layers have been revealed, along with a painted inscription in the circular baseline of the central dome. The beginning of the inscription in the west part of the circular baseline has been lost. The inscription – with several effaced letters – is partially preserved: THC KAI in the north part of the circular baseline, CΑΛΕΥΘΗCΕΤΑΙ Ω ΕΘΕΜΕΛΙΩΤΟ in the east part (Fig. 2), and ΔΕ Ο ΤOΙΟΥΤΟC ΝΕΟC ΥΠΟ ΑΘΑΝΑCΙΟΥ ΤΟΥ ΟCΙΟΤΑΤΟΥ in the south part of the circular baseline (Figs. 3, 4, 5, and 6). The dedicatory inscription can be restored as follows (Fig. 7): [ἐγὼ ἐστερέωσα τοὺς στύλους αὐ]τῆς καὶ [εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα οὐ] σαλευθήσεται [---] ῳ ἐθεμελίωτο δὲ ὁ τοιοῦτος νεός ὑπὸ Ἀθανασίου τοῦ ὁσιοτάτου .

Who is Athanasius mentioned in the inscription? The monastic tradition speaks of three aristocrats from Adrianople, Nicolaus, Athanasius, and Antonius, who arrived on Mt. Athos in order to cloister and, following the encouragement of St. Athanasius the Athonite, settled in a ruined monastery, which they rebuilt [7, pp. 210-213]. This episode, however, is not mentioned in the two Vitae of St. Athanasius. Regardless, the names mentioned in the tradition are also mentioned in written sources, albeit from differing time periods; all three were abbots of the monastery. In the first known mention of the monastery of Vatopedi, in a document from 985, Nicolaus is designated as abbot [3, no. 7.5, 63]. A few decades after Nicolaus, the energetic abbot Athanasius is mentioned in written sources from 1020 until 1048 [3, no. 24.24; 2. no. 4.41]. The abbot Antonius is mentioned in documents of the next century, in particular of 1142 [1, no. 3.43].

Therefore, Athanasius, who is recorded in the inscription, can be identified with the abbot Athanasius mentioned in the documents from 1020 until 1048. Besides, as the archaeological research has shown, Athanasius was buried in a tomb in the Catholicon [19, pp. 143-146].

It is noteworthy indeed that the inscription refers to the construction of the church ( ὀ τοιοῦτος νεός ) under Athanasius. The use of the Homeric word νέος , meaning church ( ναός ), is remarkable. Of interest for the presentation of the patron is the epithet accompanying his name. The epithet ὁσιοτάτου indicates that Athanasius was dead at the time the inscription was written. On the basis of the documents, it seems that Athanasius died around or after the middle of the eleventh century. Therefore, the inscription on the dome was composed at that period, after Athanasius’ death.

Athanasius was an active patron involved in the early history of Vatopedi. The crucial topic that the inscription concerns is the period of the construction of the Catholicon, as it clearly stated that Athanasius built the church. Therefore, the construction of the Catholicon should be placed between 1020 and 1048, at the time Athanasius was mentioned as the abbot of the monastery, yet it seems that he was dead at the time the inscription was written.

The inscription likely implies that another earlier church existed, yet it is obscure whether it is the early Christian basilica partially unearthed some decades ago under the Catholicon [18] or another church. It is undoubted that the monastery of Vatopedi was built on the location of a pre-existing establishment; the early Christian Basilica and other buildings, which are currently being excavated around the Catholicon (Fig. 8), are parts of it.

Mindful of the typological similarities that the Catholicons of Iviron [13, p. 287] and Vatopedi have, as well as the revealed dedicatory inscription in the dome of the Catholicon in Vatopedi, it seems that the Catholicon of Iviron, whose nucleus was built in the last twenty years of the tenth century [16], was the model for that of Vatopedi.

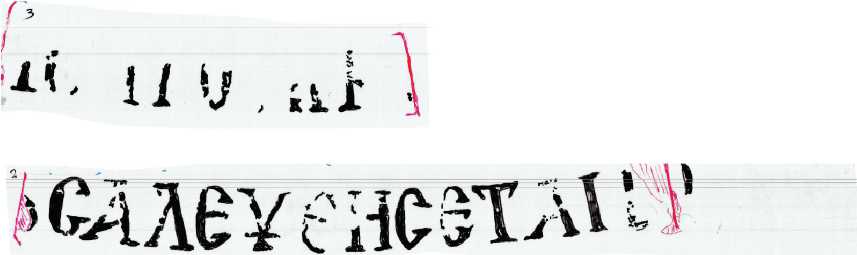

The inscription on the copper ring around the central omphalion 4 of the pavement of the Catholicon in Iviron, first published by Millet, Pargoire, and Petit [15, p. 70, no. 231], has recently attracted the attention of the author [10, pp. 187-188]; it reads as follows (Fig. 9): Ἐγὼ ἐστερέωσα τοὺς στύλους αὐτῆς καὶ εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα οὐ σαλευθήσεται Γεώργιος μοναχὸς ὁ Ἴβηρ καὶ κτήτωρ. This opus sectile 5 pavement of the Ca-tholicon was constructed around the mid-eleventh century as part of the renovations commissioned by George Agiorites, as its abbot (1045–1056). The patron George (Γεώργιος μοναχὸς ὁ Ἴβηρ καὶ κτήτωρ) cited in the inscription is George I, who carried out renovations to the Catholicon during his highly creative office as abbot of the monastery (from 1019 until 1029), according to the Vita of George Agiorites. Therefore, the donor activity recorded in the inscription concerns an earlier phase of the Catholicon, carried out under the patronage of George I [10, p. 188].

It has been claimed with reservations by P. Mylonas that the inscription (which mentions George I) is a later copy of a pre-existing one from an earlier pavement created by George I, who carried out renovations in the Catholicon as abbot between 1019 and 1029 [9, p. 42]. It is a fact that similar examples of donor inscriptions that appear to copy earlier ones are encountered in Mt Athos. I just mention the inscription on the outer west wall of the main church of the chapel of Sts Anargyroi in Vatopedi (overpainted in 1847), which seems to copy that of an earlier painting layer, financed by the Serbian despot John Unglesis (1365–1371) [8, pp. 165-166].

Also, the removed inscription of the church of the cell (and early monastery) of St. John the Forerunner, a dependency of the monastery of Docheiari. It was rebuilt in 1695 under the former abbot ( προηγούμενος ) Anastasius, seems to copy in the first part of the text) the original inscription of the church of the old monastery, founded, as it is stated, during the reign of Andronicus II Paleologus: Κατά τά ςωγ΄ ἐκτίσθει κ(αὶ) / ἀνιστορίθει ὁ θεῖος οὗτος κ(αὶ) πάν/σεπτος ναὸς τοῦ θείου καὶ ἐνδόξου προφήτου / Προδρόμου κ(αὶ) Βαπτιστοῦ Ἰω[ά]ννου· ἐπὶ τῆς βα/σιλείας τοῦ πανευσεβεστάτου βασιλέως / Ἀνδρονίκου τοῦ Παλεολόγου· νῦν δὲ ἐ/κ βάθρων ἀνεκενίσθη διὰ συνδρομῆς / κ(αὶ) ἐξόδου τοῦ πανοσιωτάτου προηγουμένου Ἀνα / στασίου ἐκ τῆς ἱερᾶς μονῆς τοῦ Δοχιαρίου· δικαίβον / τος κυροῦ Βαρθολομαίου μοναχοῦ ἐν μηνὶ Μαίω / ἔτους, ζσγ· ἀπὸ Χ(ριστο) ῦ αχ Ϟ ε [12, pp. 301-303] .

As for the donor activity recorded in the inscription on the pavement of the Catholicon in Iviron, I am in favor of another interpretation. The commemoration of George I could reflect the posthumous restoration of his memory and the recognition of his patronage in a later period under George Agiorites, at the time the accusations against George I of conspiracy against the emperor Romanus III Argyrus (1028–1034) had been dropped. It was for this reason that, shortly before the middle of the eleventh century, the remains of George I were removed from Mono-vata, where he had been exiled, and reburied in a tomb in the lite of the Catholicon. The memory of George I was strongly revered in the monastery after the mid-eleventh century thanks to George Agiorites [10, pp. 187-188].

Conclusions. Therefore, the mid-eleventhcentury inscription on the pavement of the Ca-tholicon in Iviron states its renovation occurred some years earlier, under George I, during his office as abbot (1019–1029) [9, p. 42]. From this point of view and on the basis of the available evidence this dedicatory inscription is a unique example in Mt Athos to my knowledge. In other words, there is an interaction between the inscription and the collective monastic memory, since the text vitalizes and restores the significant role of an earlier abbot and patron, who was unfairly accused of conspiracy.

The aforementioned dedicatory inscriptions in Vatopedi and Iviron appear to have strong similarities in their structure. The phrase Ἐγὼ ἐστερέωσα τοὺς στύλους αὐτῆς , common to both texts, comes from Psalm 74: … διότι ἐγὼ ἰδιοχείρως ἐστερέωσα τοὺς στύλους καὶ τὰ θεμέλιά τας ... In addition, the phrase καὶ εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα οὐ σαλευθήσεται comes from Psalm 111: … εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα οὐ σαλευθήσεται, εἰς μνημόσυνον αἰώνιον ἔσται δίκαιος ... As many other known ones, they reproduce quotations from the psalter [17, p. 152].

The majority of the Byzantine inscriptions on Athos occur at the interior, chiefly on the wall paintings. Although the practice of dedicatory texts on pavements and domes is rather scarce, the position of the inscriptions in the dome of the Catholicon in Vatopedi and in the pavement of the Catholicon in Iviron is entirely suited to their content meaning. Both aimed to accentuate the symbolic value of these architectural elements, since they symbolize the celestial (the dome) and the earthly (the pavement). In analogous cases, another common text to appear on door lintels is the citation of Psalm 117, 20: Αὕτη ἠ πύλη τοῦ Κυρίου δίκαιοι εἰσελεύσονται ἐν αὑτῇ [4, pp. 225226; 5, passim].

The aforementioned dedicatory inscriptions memorialize the donation or the renovation of Catholicon in middle Byzantine Athos, bespeak the important role of the abbots, and carry the stamp of their personalities. Especially, the recent finding in Vatopedi seems to be the earlier dedicatory inscription related to the construction of the Catholicon of a large coenobium. It occupied the second position in the Athonite hierarchy, as it is stated in the Typikon of Constantine IX Monomachus (1045) [14, p. 157]. Along with the invocation of the founder of the old monastery of Trochalas on the door lintel, which comes from the Catholicon (late tenth-early eleventh century) [12, pp. 284-285], they appear to be the only known middle Byzantine dedicatory inscriptions that state named founders of Athonite churches. A later known example mentions upper-class patrons coming from the Catholicon of Pantocrator, built in 1362–1363 under the eminent dignitaries John Primicerius and Alexius Stratopedarches [8, pp. 160-161].

Dedicatory inscriptions create the ideological context that the patrons aspire to promote for themselves through sponsoring the monastic foundations. Our knowledge on the role of church officials and especially of abbots in Middle Byzantine Athonite patronage is also confirmed by the aforementioned epigraphic testimonies. Especially, the case of inscription in Vatopedi offers valuable documentation of the participation of the abbot Athanasius in the construction of the Ca-tholicon; his substantial role in the constructional history of the monastery was until now unknown from other sources.

Despite the similarities that both inscriptions have in their structure, there is a difference in content. The inscription in the dome of the Catholicon inVatopedi refers to its founding under the abbot Athanasius, while the other one on the pavement of the Catholicon in Iviron states its renovation carried out earlier under George I.

All in all, the recently uncovered dedicatory inscription of the monastery of Vatopedi and the inscription on the Catholicon of the monastery of Iviron are important examples of promoting church officials in the donation or renovation of the Catholicons in the flourishing Athos during the eleventh century. Through targeted expressions containing psalms, the patron’s images are constructed, and their reputation after their death is strengthened.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to express my deepest gratitude to Abbot Archimandrite Ephrem for granting me permission to publish photographs of the inscription. The drawing of the inscription published here was drawn by Nikolaos Stoumpos, conservator of artworks (Ministry of Culture / Greece).

NOTES

-

1 The scientific editing is realized by Yury Vin.

-

2 Here follows a selection of notable entries from the varied bibliography [13, pp. 266-267; 20, pp. 184189; 6, pp. 29-35; 12; 8; 21, pp. 128-140].

-

3 Phiale – a shallow bowl at the entrance in a church, which means for water utilized in liturgical and ceremonial using ( Editor ).

-

4 Diminutive form, see “omfalos” – literally “the navel,” the sacred symbol of the creation at the central point of the church ( Editor ).

-

5 Opus sectile – the ancient mosaic technology of laying out polished color ashlars ( Editor ).

APPLICATION

Fig. 1. Monastery of Vatopedi; Catholicon (photo by D. Liakos, 2018)

Fig. 2. Monastery of Vatopedi; Catholicon; dedicatory inscription; detail 1 (photo by D. Liakos, 2024)

Fig. 3. Monastery of Vatopedi; Catholicon; dedicatory inscription; detail 2 (photo by D. Liakos, 2024)

Fig. 4. Monastery of Vatopedi; Catholicon; dedicatory inscription; detail 3 (photo by D. Liakos, 2024)

Fig. 5. Monastery of Vatopedi; Catholicon; dedicatory inscription; detail 4 (photo by D. Liakos, 2024)

Fig. 6. Monastery of Vatopedi; Catholicon; dedicatory inscription; detail 5 (photo by D. Liakos, 2024)

- йРТеоеЖ hi ото д eGTOW^

Тб^Жо^

^ ^одеждомУ

Fig. 7. Monastery of Vatopedi; Catholicon; dedicatory inscription; drawing (by N. Stoumpos)

Fig. 8. Monastery of Vatopedi; part of an early middle-Byzantine building near Catholicon (photo by D. Liakos, 2025)

Fig. 9. Monastery of Iviron; Catholicon; opus sectile pavement; dedicatory inscription (photo by D. Liakos, 2008)