Emotional effect of teachers’ discourse in a multicultural classroom

Автор: Zhou Qing, Laiche Souhila, Larina Tatiana V.

Журнал: Вестник Волгоградского государственного университета. Серия 2: Языкознание @jvolsu-linguistics

Рубрика: Дискурсивные аспекты изучения эмоций и эмоциональная лингвоэкология

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.22, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The manifestation, meaning, categorization of emotions, as well as the factors that cause them, have cultural characteristics. To build successful intercultural interaction it is necessary to be aware of them. This study explores classroom discourse and emotions of international students in a multicultural classroom. Our goal is to determine what emotions the discourse of Russian teachers evokes in students from different lingua-cultures and which speech acts have an emotional perlocutionary effect. The material was obtained through a questionnaire with the participation of 70 international students (45 Chinese and 25 Algerian). We focus on emotions and emotional states of surprise, happiness, sadness and offense. Being drawn on qualitative and quantitative methods the comparative analysis showed that the behavior of Russian teachers is more likely to surprise Chinese students than Arab ones, besides Chinese students experience negative emotions and states more often than Arabs which may indicate a greater cultural distance. In relation to speech acts that evoke the emotions, we identified some similarities and differences, which are discussed through the type of culture and cultural values. The results contribute to the study of culture specific features of emotions in communication. They specify the factors that evoke emotions in students belonging to different lingua-cultures, and can contribute to the successful interaction of Russian teachers with international students in a multicultural classroom.

Emotion, emotionalization, classroom discourse, emotional effect, multicultural classroom, cultural values, communicative ethnostyle

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149142302

IDR: 149142302 | УДК: 81’23:371.32 | DOI: 10.15688/jvolsu2.2023.1.10

Текст научной статьи Emotional effect of teachers’ discourse in a multicultural classroom

DOI:

Language and emotion are the two fundamental systems involved in communication. Their correlation is in the focus of numerous interdisciplinary studies (e.g.: [Alba-Juez, 2018; Alba-Juez, Larina, 2018; Foolen, 2012; Ionova, 2015; 2019; Ionova, Shakhovskiy, 2018; Lerner, Rivkin-Fish, 2021 ; Mackenzie, Alba-Juez (eds.), 2019; Shakhovsky, 2008; 2009; 2015; Shakhovskiy, 2018; Wierzbicka, 1999; etc.]). They show that today, as Shakhovsky stated, the study of emotions in language is one of the most relevant linguistic problems [Shakhovsky, 2008, p. 9].

Scholars draw attention to the emotions in social life (e.g.: [Bericat, 2016; Olson, Bellocchi, Dadich, 2020]) and highlight “the pervasive presence of emotionality in contemporary culture, where emotions become more important and formative than anything else” [Lerner, Rivkin-Fish, 2021, p. 5]. Emotionalisation viewed as legitimization and intensification of emotional discourse in public domain is observed in various settings, discourses and genres (e.g.: [Breeze, 2020; Larina, Ponton, 2022; Maíz-Arévalo, 2018;

Musolff, 2021; Ozyumenko, Larina, 2021; Bull, Waddle, 2021; Zappetini, Ponton, Larina, 2021]), including those which are traditionally regarded as non-emotional (e.g.: [Belyakov, 2015; Mackenzie, 2018]). It is also relevant in academic discourse [Deveci, Midraj, El-Sokkary, 2023; El-Dakhs et al., 2019; Lerner, Zbenovich, Kaneh-Shalit, 2021]. Shakhovsky rightly noted that emotions have become the most important components of the mind, thinking and linguistic consciousness of a modern person belonging to any lingua-culture [Shakhovsky, 2008, p. 5].

While emotions are universal, how they are experienced, expressed, perceived and variously regulated across cultures [Dewaele, 2010; 2014; Goddard, Ye, 2014; Larina, 2015; 2019; Wierzbicka 1999; 2001; etc.]. Differences between languages and cultures have an effect on how speakers perceive or experience their own and other’s feelings, and might lead to misunderstandings in intercultural communication. In the context of intercultural interactions, the language of emotion takes a special importance [Gallois, 1993].

Emotions are recognized as being dependent on a type of culture and may be described with a set of sociocultural parameters and a type of culture. Matsumoto [1989] developed an emotional hypothesis based on the dimensions of culture proposed by Hofstede [Hofstede G., Hofstede G.Y., 2004] and suggested that (1) Expected power distance is connected to emotion perception; if high/low power distance is overlooked in communication, it might induce cultural shock; (2) Individualism-driven cultures will foster the expression of negative emotions and varied emotional judgments; (3) Anxiety or dread of the unknown is connected with uncertainty avoidance; (4) Gender differences in emotional expression and perception are to be expected in a masculine culture. Hofstede [Hofstede G., Hofstede G.Y., 2004] noted that in weak uncertainty avoidance cultures emotions should not be shown and in masculine cultures men should be emotionally reserved.

There are two basic approaches for looking into how language and emotion interact: one is investigating at how language affects emotion, while the other focuses on studying at how emotion influences language [Alba-Juez, Larina 2018, p. 10]. People typically convey emotions through language, and the expression of emotions takes place at all linguistic levels: phonological, morphological, lexical, syntactic, semantic and pragmatic levels (e.g.: [Foolen, 2012, p. 349; Shakhovsky, 2009]). Additionally, they are capable of conceptualising a variety of emotions by using verbs like love, surprise, and hate; adjectives like happy, sad, and nouns like sadness or jealousy [Foolen, 2012, pp. 350-351] and express them by using these words. At the same time, language has the potential to affect how we feel or how we perceive the words of our interlocutor. Members of all cultures engage in daily interactions with these two systems simultaneously: any linguistic statement is made and understood in a natural discourse inside an emotional context.

One of the most crucial categories of speech acts in Austin’s theory is the perlocutionary speech act [Austin, 1975, p. 105]. It is focused on how a speech can achieve a certain effect on the hearer, which is also well known as perlocutionary effect [Austin, 1975, p. 121]. As a kind of perlocutionary speech acts, emotive speech act has characteristics that impact the emotions in communication behavior [Piotrovskaya, Trushchelev, 2020]. Moreover, emotions are related to politeness (e.g.: [Langlotz, Locher, 2017; Spencer-Oatey, 2011; Yuasa, 2001]). Scholars single out emotive politeness [Larina, 2019], which concerns emotional sensitivity and consideration for the other’s feelings, and appears to be (pre)determined by the sociocultural context [Larina, Ponton, 2022].

According to Ekman, there are six basic emotions – fear, anger, disgust, surprise, happiness, and sadness [Ekman, Cordaro, 2011]. More complexed emotions can also be studied from the combination of the six basic emotions. In the lexicon of emotions there is a dichotomy in the type of evaluative signs. For example, “happiness” is an emotion that is affected by the achievement of certain goals or ambitions, “sadness”, on the contrary, can be evoked by disappointment due to a failure.

In this study, we explore how teachers’ discourse affects their students’ emotional states in the classroom settings and focus on emotions/ emotional states of surprise, happiness, sadness and offense. The classroom is an emotional environment. During classroom activities, both the teacher and the students experience a range of emotions, from positive to negative [Hargreaves, 1998; Schutz, Lanehart, 2002]. A good and healthy emotional teaching atmosphere is essential to the success of education and the achievements of students [Becker et al., 2014; Bellocchi, 2015; Frenzel et al., 2009; Sutton, Wheatley, 2003]. On the contrary, an unhealthy classroom communication climate can lead students to frequent complaints about communication problems with their teachers, claiming to be offended or disappointed by them [Gretzky, Lerner, 2021, p. 212]. Negative emotions are a major factor explaining why many students do not live up to their potential and fail to pursue the educational career that would correspond to their abilities and interests [Pekrun, 2014, pp. 14-15]. Moreover, according to Denzin [1984], teaching and learning involve emotional understanding. Which is “an intersubjective process requiring that one person enter into the field of experience of another and experience for herself the same or similar experiences experienced by another” [Denzin, 1984, p. 137]. However, emotional misunderstandings between students and teachers may also occur especially in a multicultural classroom due to the differences in culturespecific communicative styles of teacher – student interaction.

When teachers come from different sociocultural backgrounds than their students, the emotional disparities become much wider. Emotional misunderstanding is a serious barrier in the educational process that prevents a comfortable psychological atmosphere in the classroom. Thus, studying the emotional understanding of teachers and students from various cultural backgrounds can provide us with useful insights and clues on how to change teaching and learning more broadly in this regard [Hargreaves, 1998]. Nevertheless, researchers seldom pay attention to emotional interactions between students and teachers from different cultural backgrounds in the classroom environment. This paper attempts to fill this gap by conducting an empirical study of emotional effect of Russian teacher discourse on Chinese and Arabic students.

Material and methods

The goals of the current study were to identify the variables that affect students’ emotional responses to Russian teachers’ speech acts in classroom settings and to find out how the discourse of Russian teachers in multicultural classrooms affects Chinese and Arab students. As was already established, teacher’s communicative behaviours can either positively or negatively stimulate the emotions of their students. We will therefore focus on four emotional responses in this study, namely surprise, happiness, sadness and offense. First, we predicted that students from different cultural backgrounds would experience some surprise finding their teacher’s behavior sometimes unexpected. However, surprise can be either positive or negative because it is brought on by either unanticipated or incorrectly anticipated characteristics (e.g.: [Scherer, 1984]). Both positive “happy” and negative “unhappy/sad” emotions will be the subject of our research. Based on the sadness, we looked into another negative emotion called “offense.” Feeling offended is a negative emotion brought on by another person’s verbal or nonverbal act or omission. Damage to one’s image and selfimage is what leads to feeling insulted, which is one of the so-called “self-conscious emotions” [Lewis, 2008; Poggi, D’Errico, 2018].

The study employs a mixed-methods approach that combines quantitative and qualitative methods of achieving the intended goals. The results were discussed drawing on cultural studies [Hofstede G., Hofstede G.Y., 2004].

The material for the study was obtained through a questionnaire. The questionnaire is divided into two parts: the first part contained four questions that allowed us to gauge how frequently various emotions (surprise, happiness, sadness and offense) occur. The participants were asked to identify the frequency of their emotions experienced in the international classrooms while being exposed to the Russian teachers’ discourse on the scale (Never/Seldom/Sometimes/Often/ Always). The second part of the questionnaire is a discourse completion test (DCT), where the students were asked to specify the situation in which they experienced the forementioned emotions and provide examples of the Russian teachers’ discourse for each situation (see Appendix). Participants were recognized as Chinese and Arab students studying at Russian universities and included 45 Chinese students, and 25 Arab (Algerian) students.

The study was aimed at answering the following research questions:

-

1. How often do Chinese and Arab students experience emotions of surprise, happiness, sadness and offense caused by their Russian teacher’s discourse?

-

2. What actions/acts of the teacher may surprise, delight, upset and offend Chinese and Arab students?

-

3. Are there any similarities and differences in the emotional perception of the Russian teacher’s discourse by Chinese and Arab students?

-

4. Could the students’ emotions and the factors, which evoke them, be related to the differences in students’ culture, values and communicative ethnostyles?

Results and discussion

-

1. Surprise

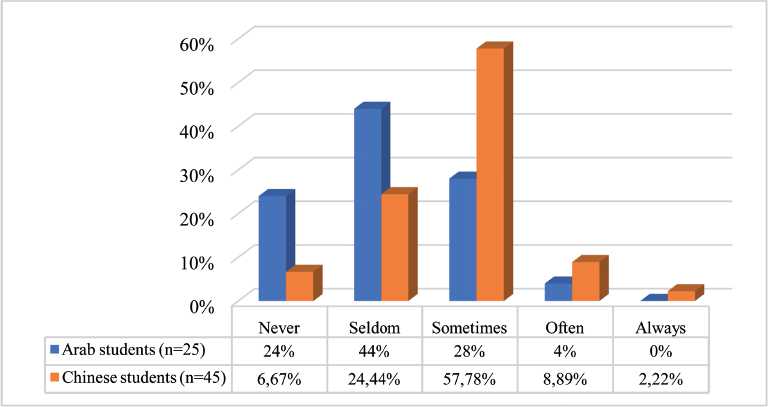

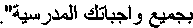

The findings showed that the verbal behavior of Russian teachers may surprise both Chinese and Arab students. However, significant differences were found in the frequency of this emotion. The majority of students from China (57.78%) responded they were “sometimes” surprised by the mode of communication of their Russian teachers, “seldom” was chosen by 24.44%, while 8.89% chose “often” and 6.67% chose “never”. Some students (2.22%) said they “always” feel surprised by their Russian teacher.

The majority of Arab participants selected “seldom” (44%), followed by 28% “sometimes” and 24% “never,” with only 4% selecting “often” feeling surprised. This suggests that the Chinese students have more unexpected experiences in the Russian teachers’ classrooms than the Arab students do (Fig. 1).

Moreover, the respondents’ reactions can provide some insight into the teachers’ acts or utterances which international students find unexpected and surprising.

The analysis of the Chinese material showed that the situations where the students feel surprised mostly deal with Russian teachers’ expertise, which exceeds their expectations rather than with the performed speech acts. In our Chinese material, one of the most frequent response concerned the Russian teachers’ knowledge of China and Chinese culture:

-

(1) When we were talking about world religions, I was surprised when the Russian teacher talked about Chinese Taoism and Confucianism 2.

当我们谈论到世界宗教的时候,俄罗斯老师 谈论到中国的道教和儒教,我感到很吃惊。

-

(2) The teacher talked about some Chinese situations and culture in the classroom. Once the teacher talked about the “996 work schedule”3 in China and network words like “Lying flat”4; a philosophy teacher talked about Chinese Confucius, Mencius, Mozi and other Chinese classical philosophy, it was very unexpected and I felt surprised.

老师在课程中讲了一些中国以及中国文化 的情况。有一次老师讲了中国的“996制度”还 有“平”等网络词;还有哲学课的老师会把中国 孔子孟子墨子等古典哲学精讲,很意外很惊喜。

Fig. 1. Frequency of surprise experienced by Chinese and Arab students in the class

In addition, Chinese students were surprised by the knowledge and additional skills of their teachers:

-

(3) Russian teacher said that she studied five foreign languages.

俄罗斯老师说她学过五门外语。

Another factor that caused the students’ surprise was the positive attitude of their Russian teachers and support. In some instances where the students anticipated criticism or rejection, they were instead surprised by the support and encouragement they received from their Russian teachers. For example, when being self-conscious they received positive reinforcement (4) or understanding (5) from their teachers:

-

(4) When I gave a PowerPoint presentation, I was bad, but the teacher eventually stated, “Very nice!

当我做ppt报告时,我总感觉不太好,老师 最后却说:“很好!”

-

(5) I felt sick and asked the teacher for leave, and the teacher responded, “Don’t worry, of course you can.”

请病假,老师说:“别担心,当然可以。”

Some of the students mentioned that they are surprised that the style of Russian teachers is rather formal. Most of Russian teachers address them formally, using the plural pronoun vy , say thank you and sorry :

-

(6) The Russian teachers are always very polite, addressing us with “вы” and often saying things like thank you and apologies , which surprise me.

俄罗斯老师总是很客气,用“вы”称呼 我们,并且经常说道谢,道歉之类的话,让我感 到很吃惊。

The answers of Arab students revealed some similarities and differences. The majority of them justified their surprise by emphasizing the teacher’s praise, particularly the public recognition:

-

(7) I feel surprised when the teacher praises me in front of my colleagues, and he says: “Well, done, you did an excellent job”.

'* ""1 ^ ''"''I": Jj^ij , ^Хаj^ijjllcal ул Jm Ulic iatiji"

.JUm Ja*j yai -ill

?LSllj JI J^l^j jjJI eUjAVI Jo ell 5b> l>2"

The Arab students are also surprised by the teachers’ concern and support for them:

However, many noted some cases of the teacher’s inattention to their individual problems and lack of concern, which surprised them:

-

(10) I feel surprised when my Russian teacher doesn’t care about my problem, and says: “This is not my problem”.

-

2. Happiness

tiiiiuJ »j< "; Jjiy .y ‘iMa.i ушjjl! ^jviuii i»j^j у u±ie LxUji

Thus, from Arab students’ answers, it can be inferred that they are mostly surprised by praise from teachers. Besides, the Arab students’ perception of the Russian teacher’s concern as well as lack of concern were both unexpectedly emotional, but these reactions may have been either positive or negative.

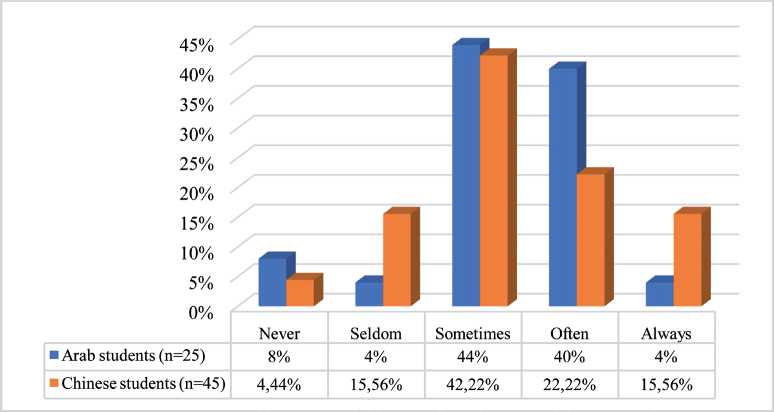

The analysis of the frequency of emotion of happiness experienced by Chinese and Arab students also revealed some similarities and differences. While the majority of both Chinese and Arab students demonstrated similarity in saying that they “sometimes” feel happy (42.22% and 44% correspondingly), the amount of the Arab students who are “often” happy turned out to be almost twice as many as the Chinese ones (40% to 22,22%) (see Fig. 2).

This would suggest that the Russian teacher’s behaviors make the Arab students feel happy more frequently than Chinese ones, though among those who are always happy, Chinese students exceeded (15,5% to 4%).

Fig. 2. Frequency of happiness experienced by Chinese and Arab students in the class

The majority of the students mentioned their enjoyable experiences in the Russian teacher’s classroom in the questionnaire. Chinese students, for instance, feel happy when Russian teachers show politeness, friendliness and kindness:

-

(11) After each lesson, one teacher thanked us for our patience, wished us good health and all the best.

有个老师每次在课后都会感谢我们的忍耐, 并且祝我们身体健康,一切顺利。

Chinese learners feel happy when Russian teachers show their respect to traditional Chinese culture:

-

(12) Russian teachers attach great importance to Chinese customs and culture (Confucianism).

俄罗斯老师很重视中国礼仪与文化(儒学)。

Receiving praise from the teacher is also one of the sources of happiness for Chinese students:

-

(13) When I was trying to recite, the Russian teacher said, “I can see that you’ve worked hard, great!” 当我努力背诵的时候,俄罗斯老师说: “你 努力了,我看到了。你很棒!”

Likewise, receiving praise from teachers makes Arab students feel happy (14)–(15):

-

(14) I feel happy when my Russian teacher praises me and says that the data, we have collected is good and varied, and he says “You are smart and you are quickly adapting to work and ideas”.

z,^! ^L'LtiJI ^1 J_^j ^—yJj3! ^3U«ii *■* fi/ LajJe ^J^^ J*-^!

^iaIsLij 4^ ^* “ *^ ^L^J £u) ^^ *^J^Aj^ A^^^4, j 5^д I^jJp ^I^a , f,jl£fl^!j J^xJl ^-4

Additionally, support from their teachers has a positive emotional effect on Arab students:

-

(15) I feel happy when my Russian teacher comforts me and says: “Everything is going to be fine”. jiui! ^jkajj yxajjll jjlluii^fjP ( «»■'; Ujje 5jLx—Ju ji2j)

-

3. Unhappiness / sadness

. "^Ijj L>yds 0A“ Py“JS" : ЛЙи .^Ы^

Thus, the findings demonstrate that both Chinese and Arab students like receiving praise or recognition and support from Russian teachers, and this is seen as a key incentive for them. The salient distinction is that Chinese students, among other things, feel happy when their Russian teachers demonstrate knowledge of Chinese culture and show respect for it.

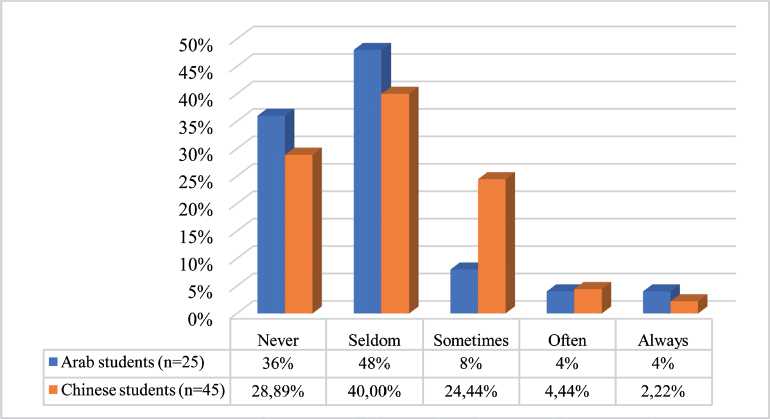

When asked about the negative emotion of sadness, the two responses with the highest percentages for both Chinese and Arab participants are “seldom” and “never” with some predominance in Chinese data, as shown in Figure 3. The number of those who “sometimes” feel unhappy with the teacher’s discourse is three times higher among Chinese students (24,44%) compared to Arab ones (8%).

This indicates that it is not very common for Arab students to feel upset or disturbed due to something involving their teachers’ behavior in the classroom. Chinese students experience higher amounts of displeasure than Arab ones.

Fig. 3. Frequency of unhappiness/sadness experienced by Chinese and Arab students

While analyzing the situations in which Chinese students feel unhappy, we found out that the majority of them are caused by harsh comments made by teachers (16)–(17). It should be emphasised that the majority of comments are in reference to their educational background and academic performance:

-

(16) The Russian teachers would criticize us unmercifully to our faces, for example by saying to our faces that our Russian expressions were very unacademic.

俄罗斯老师会当面毫不留情地批评,比如当 面说我们的俄语表达很不学术。

Chinese students find it offensive when they are criticized and opposed to Russian students:

-

(17) Russian teacher said in class that, Chinese students learn poorly, so Russian students need to put up with it.

俄罗斯老师在课上说:“中国学生水平不 高,所以俄罗斯学生需要忍耐一下。”

Russian teachers make Chinese students unhappy by ignoring “quiet” Chinese pupils not giving them a chance to participate in class discussions.

-

(18) When I knew the answer to the question, the teacher didn’t ask me to answer the question.

我知道问题答案的时候,老师没叫我回答 问题。

Only a tiny proportion of Arab students stated that they had experienced emotional depression as a result of their Russian teachers’ discourse. They only concern critical remarks.

-

(19) ‘I feel unhappy when my Russian teacher tells me that my marks are not good, and says: “I expected better results from you”.’

-

4. Offense

("uajl^Le^le LfiyHJU^I lS^*-^' l^>^ Ulifr (jJaJL jtu!

, "dL> J*2asi gjUj £3jjl i^u$" :Jj^jj . »^j^

As a result, it is evident that both Chinese and Arab students react badly to criticism, which causes them to be uncomfortable or upset, especially when it is made in front of others.

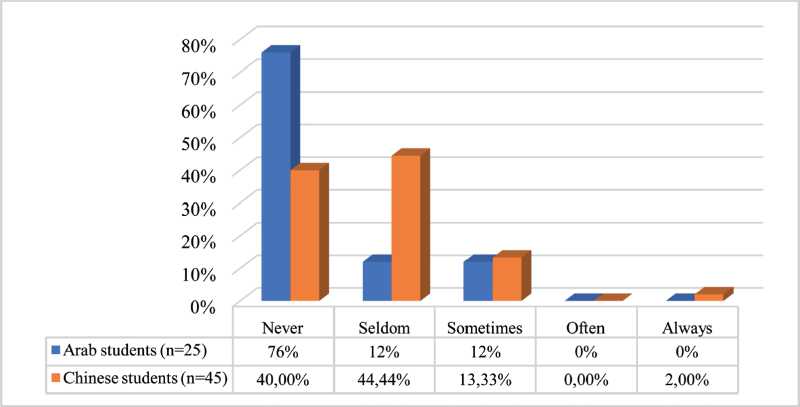

When it comes to another negative emotion – feeling offended, the results of the questionnaire are shown in Figure 4. Chinese responses were more focused on the “seldom” (44.44%) and “never” (40%) options, while 76% of the Arab participants said this “never” happened, and equal percentage of 12% went to both choices “seldom” and “sometimes”. Based on our findings, it can be said that most Arab students “never” experience the feeling of offense evoked by their Russian teacher’s discourse, while the answers of Chinese students combine “never” and “seldom” in almost equal proportions.

The few examples of the responses on this issue enable us to suggest the following.

Chinese students may feel offended if they are frequently addressed by an incorrect name (20), they may also get offended by the

Fig. 4. Frequency of offense experienced by Chinese and Arab students

teacher’s strict attitude (21). Arab students may view criticism as a source of offense (22).

-

(20) When I finished answering questions, the Russian teacher often called me by the wrong name (It was frequently offensive).

有几次,当我回答完问题,俄罗斯老师 说:“这是XXX(叫错名字)吗?”(很多次就 有点生气了)。

-

(21) When a student was five minutes late, the Russian teacher said, “Go home.”

当一个同学迟到了5分钟的时候,俄罗斯老 师说:“回家吧。”

-

(22) I feel offended when my Russian teacher tells me that my pronunciation is bad, and he says: “Your words are incorrect.”

:JAu . ^^ A^ diy^j^ ^jtLuiiy-LA? UHc 4JU yu ytdl

Discussion

The results of the study show that both Chinese and Arab students experience a set of emotions in classroom settings which are related to the Russian teacher’s discourse.

It is noted that Chinese students get surprised by the teachers’ communicative behaviors more frequently than the Arab students. This indicates that there are more cultural and communicative differences between Russian and Chinese culture in comparison with Arabic one. It is also noteworthy that, as our findings show, Chinese students experience negative emotions (sadness and offense) more often than Arab students, which would suggest that Russian teacher’s discourse implies some cultural aspects that would be perceived negatively by the representatives of Chinese culture.

Both Chinese and Arab students experience similar emotions in certain situations, for instance, it was remarked that both of them react positively to the low amount of power distance between them and their Russian teachers, to their kind attitudes and support. Positive feedback was received from both when it comes to getting praises in classrooms, in contradiction, negative emotions were expressed towards the teacher’s critical remarks.

The findings showed that Chinese and Arab students were positively surprised by the praise and support they receive from their Russian teachers in situations where they expected to be chastised or rejected. This might be due to the fact the student-teacher interactions in the Arabic and Chinese cultures tend to be stricter and more formal. Also, it can be deduced that Russian teachers tend to provide more praise to students. Furthermore, both Chinese and Arab students feel happy when their Russian teachers show them kindness, appreciating their work and culture, comforting them and congratulating them. It is worth noting that Chinese students appear to be very sensitive to hear about the topics related to their country. They react favourably to such behaviors, as the Chinese participants used the expression “ 惊喜 ” (in Eng. ‘pleasant surprise’) when discussing this. This might be explained by we-orientation of Chinese culture and we-identity [Larina, Ozyumenko, 2016] of Chinese students who perceive themselves as members of a big community rather than independent individuals.

The majority of events involving unhappy/ sad emotions are linked to critical remarks made by teachers. The findings showed that both Arab and Chinese students react negatively to criticism, which make them feel uncomfortable or unhappy. Additionally, Chinese students were particularly disturbed, uncomfortable and even upset when they heard a negative comment about their culture and when their collective face was threatened. Not to forget to mention that Chinese students feel offended when they are frequently called by incorrect names. Again, these facts might be explained by we-identity of Chinese students as well as the high value of the concept of face in Chinese culture both individual face and collective face. From the aspects of (im) politeness and emotion, it can be said that as the idea of face is linked to the conceptualization of the self, the face-challenging and face-attacks can have a negative impact on a person’s emotion [Langlotz, Locher, 2017, p. 287].

It also should be noted that Arab students mostly feel unhappy due to another reason, namely when they are criticized about their learning performance in general, and the level of Russian language proficiency in particular. In addition to that, the Arab students feel upset when some of their classmates are praised while they are not, even when they have not done anything to be praised for. Perhaps this could be explained by our observation that Arab students are eager to fulfill the feeling of accomplishment all the time through receiving positive remarks from their teachers. We suggest that the latter might be caused by their parents ‘sense of perfectionism’ (academic and professional), and how Arab parents are constantly pushing their kids to have better achievements.

On the other hand, some Arab students find it upsetting when Russian teachers seem to be not interested in their personal issues. The point is that in the Arabic context due to the social status of teachers who are considered as a guru, students feel free to discuss not only academic issues but any personal problems. As an example, in Algerian classrooms, students tend to tell their teachers about their personal problems (family issues) or financial issues in case the teacher noticed something wrong with them. This would suggest that the Algerian (Arab) teachers might be more approachable than the Russian teachers due to a shorter horizontal distance (Social Distance in terms of [Hofstede G., Hofstede G.Y., 2004]) in Algerian culture.

The findings suggest that Power Distance (or vertical distance) tends to be higher between the teachers and students in both Chinese and Arabic cultures. This assumption could be confirmed by the fact that the level of formality of students in their interaction with teachers is conventionally higher in Chinese and Arabic contexts than in Russian one. Additionally, Chinese and Arab students are addressed less formally by their native teachers, while they are addressed more formally by their Russian teachers. That indicates a salient asymmetry in teacher-student and student-teacher interaction in Chinese and Arabic contexts. Adding to that, the speech acts of thanking and apology are mostly noticed in the Russian teachers’ communicative behaviors who apologize or thank the students quite frequently, which is something uncommon in both Chinese and Arabic cultures.

From the above results it is clear that students from Chinese and Arabic cultural backgrounds have some differences in their emotional and communicative experiences as well as expectations. Based on the data of our study, it can be concluded that the student-teacher interactions vary across cultures due to the differences in social organization, identity and cultures values.

Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the emotional impact that Russian teacher’s discourse has on Chinese and Arab students. We aimed to find out the similarities and differences in their emotional perceptions and specify the teacher’s speech acts that have an emotional perlocutionary effect on Chinese and Arab students in classroom settings.

The findings show how different cultural backgrounds can affect the emotional effects in the teacher-student interactions and how something that is normal in one culture can be perceived as unusual and surprising, sometimes upsetting or even offensive in another. This suggests that both learners and educators need to be aware of one another’s cultural backgrounds in order to prevent any negative effects that could result in misinterpretation and disappointments.

Since this study was performed on the limited language material, its results are preliminary, and further studies are needed. Nevertheless, our findings appear to confirm that teacher’s discourse can have an emotional effect on students with other cultural backgrounds due to differences in lingua-cultural identity and communicative ethnostyles. For teachers involved in multicultural classes, it is particularly important to be aware of these differences to prevent negative emotions of students and to create a comfortable emotional atmosphere.

NOTES

-

1 This publication has been supported by the RUDN University Scientific Projects Grant System,

project № 050734-2-000.

Публикация выполнена при поддержке Программы стратегического академического лидерства РУДН, проект № 050734-2-000.

APPENDIX

Questionnaire

-

1. How often does the behavior of your Russian teacher

-

a) surprise you, look unusual or unexpected (удивляет Вас)

NeverD

seldom □

sometimesD

often □

alwaysD

-

b) make you happy (радует вас)

NeverD

seldom □

sometimesD

often □

alwaysD

-

c) make you unhappy, sad (огорчает Вас)

NeverD

seldom D sometimesD

often D

alwaysD

-

d) make you feel offended (обижает Вас)

NeverD

seldom D sometimesD

often D

alwaysD

-

2. Could you please specify such situations and give an example of what your teacher would say. More than one example would be appreciated.

-

a) It surprises me when my Russian teacher..................................................................................................................

and says: “'

-

b) It makes me happy when my Russian teacher

and says: “'

-

c) It makes me unhappy and sad when my Russian teacher

and says: “

-

d) It offends me when my Russian teacher

and says: “

Список литературы Emotional effect of teachers’ discourse in a multicultural classroom

- Alba-Juez L., 2018. Emotion and Appraisal Processes in Language. Gomez Gonzalez M. de los A., Mackenzie J.L., eds. The Construction of Discourse as Verbal Interaction. Amsterdam, Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 227-250. DOI: https://doi. org/10.1075/pbns.296.09alb

- Alba-Juez L., Larina T.V., 2018. Language and Emotion: Discourse-Pragmatic Perspectives. Russian Journal of Linguistics, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 9-37. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22363/2312-9182-2018-22-1-9-37

- Austin J.L., 1975. How to Do Things With Words. London, Oxford University Press. 192 p.

- Becker E.S., Goetz T., Morger V., Ranellucci J., 2014. The Importance of Teachers' Emotions and Instructional Behavior for Their Students' Emotions - An Experience Sampling Analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, vol. 43, pp.15-26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j. tate.2014.05.002

- Belyakov M.V., 2015. Kharakter emotivnosti diplomaticheskogo diskursa [Emotive Character of Diplomatic Discourse]. Russian Journal of Linguistics, no. 2, pp. 124-132.

- Bellocchi A., 2015. Methods for Sociological Inquiry on Emotion in Educational Settings. Emotion Review, vol. 7, iss. 2, pp. 151-156. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.1177/1754073914554775

- Bericat E., 2016. The Sociology of Emotions: Four Decades of Progress. Current Sociology, vol. 64, iss. 3, pp. 491-513. DOI: https://doi.org/10. 1177/0011392115588355

- Breeze, R., 2020. Angry Tweets: A Corpus-Assisted Study of Anger in Populist Political Discourse. Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict, vol. 8, iss. 1, pp. 118-145.

- Bull P., Waddle M., 2021. "Stirring It Up!" Emotionality in Audience Responses to Political Speeches. Russian Journal of Linguistics, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 611-627. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22363/2687-0088-2021-25-3-611-627

- Denzin N.K., 1984. On Understanding Emotion. San Francisco, Washington, London, Jossey-Bass Publ. 285 p.

- Deveci T., Midraj J., El-Sokkary W.S., 2023. The Speech Act of Compliment in Student -Teacher Interaction: A Case Study of Emirati University Students' Attitudes. Russian Journal of Linguistics, vol. 22, no. 1. DOI: https://doi. org/10.22363/2687-0088-30051

- Dewaele J.M., 2010. Emotions in Multiple Languages. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan. 264 p.

- Dewaele J.M., 2014. Culture and Emotional Language. Sharifian F., ed. The Routledge Handbook of Language and Culture. Oxford, Routledge, pp. 357-370.

- Ekman P., Cordaro D., 2011. What Is Meant by Calling Emotions Basic. Emotion Review, vol. 3, iss. 4, pp. 364-370. DOI: https://doi. org/10.1177/1754073911410740

- El-Dakhs D.A.S., Ambreen F., Zaheer M., Gusarova Yu., 2019. A Pragmatic Analysis of the Speech Act of Criticizing in University Teacher-Student Talk: The Case of English as a Lingua Franca. Pragmatics, vol. 29, iss. 4, pp. 493-520.

- Foolen A., 2012. The Relevance of Emotion for Language and Linguistics. Foolen A., Lüdtke U.M., Racine T.P., Zlatev J., eds. Moving Ourselves, Moving Others: Motion and Emotion in Intersubjectivity, Consciousness and Language. Amsterdam, Philadelphia, John Benjamins, pp. 349-369.

- Frenzel A.C., Goetz T., Stephens E.J., Jacob B., 2009. Antecedents and Effects of Teachers' Emotional Experiences: An Integrated Perspective and Empirical Test. Schutz P., Zembylas M., eds. Advances in Teacher Emotion Research. Boston, Springer, pp. 129-151. DOI: https://doi. org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0564-2_7

- Gallois C., 1993. The Language and Communication of Emotion: Universal, Interpersonal, or Intergroup? American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 36, iss. 3, pp. 309-338. DOI: https://doi. org/10.1177/0002764293036003005

- Goddard C., Ye Zh., 2014. Exploring "Happiness" and "Pain" Across Languages and Cultures. International Journal of Language and Culture, vol. 1, iss. 2, pp. 131-148. DOI: https://doi. org/10.1075/ijolc.1.2.01god

- Gretzky M., Lerner J., 2021. Students of Academic Capitalism: Emotional Dimensions in the Commercialization of Higher Education. Sociological Research Online, vol. 26, iss. 1, pp. 205-221. DOI: https://doi.org/10. 1177/1360780420968117

- Hargreaves A., 1998. The Emotional Practice of Teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, vol. 14, iss. 8, pp. 835-854. DOI: https://psycnet. apa.org/doi/10.1016/S0742-051X(98)00025-0

- Hofstede G., Hofstede G.Y., 2004. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. S.l., McGraw Hill Professional. 300 p.

- Ionova S.V., 2015. Emotsionalnye effekty pozitivnoy formy obshcheniya [Emotional Effects of Positive Forms of Communication]. Russian Journal of Linguistics, no. 1, pp. 20-30.

- Ionova S.V., 2019. Lingvistika emotsiy - nauka budushchego [Linguistics of Emotions as Science of the Future]. Izvestiya Volgogradskogo go sudar stvennogo pedagogicheskogo universiteta [Izvestia of the Volgograd State Pedagogical University], vol. 1, no. 134, pp. 124-131.

- Ionova S.V., Shakhovskiy V.I., 2018. Prospektsiya lingvokulturologicheskoy teorii emotsiy Anny Vezhbitskoy [Anna Wierzbicka's Linguocultural Theory of Emotions in the Development Dynamics]. Russian Journal of Linguistics, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 966-987. DOI: 10.22363/23129182-2018-22-4-966-987

- Langlotz A., Locher M.A., 2017. (Im)politeness and Emotion. Culpeper J., Haugh M., Kadar D., eds. The Palgrave Handbook of Linguistic (Im)politeness. London, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 287-322. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-37508-7_12

- Larina T.V., 2015. Pragmatika emotsiy v mezhkulturnom kontekste [Pragmatics of Emotions in Intercultural Context]. Russian Journal of Linguistics, no. 1, pp. 144-163.

- Larina T.V., 2019. Emotivnaya ekologichnost I emotivnaya vezhlivost v angliyskoy i russkoy anonimnoy retsenzii [Emotive Ecology and Emotive Politeness in English and Russian Blind Peer-Review]. Voprosypsikholingvistiki [Journal of Psycholinguistics], vol. 1(39), pp. 38-57. DOI: 10.30982/2077-5911-2019-39-1-38-57

- Larina T., Ozyumenko V., 2016. Ethnic Identity in Language and Communication. Cuadernos de Rusística Española, vol. 12, pp. 57-68. URL: http://revistaseug.ugr.es/index.php/cre/issue/ view/358/showToc

- Larina T.V., Ponton D.M., 2022. I Wanted to Honour Your Journal, and You Spat in My Face: Emotive (Im)politeness and Face in the English and Russian Blind Peer Review. Journal of Politeness Research, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 201-226. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/pr-2019-0035

- Lerner J., Rivkin-Fish M., 2021. On Emotionalisation of Public Domains. Emotions and Society, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 3-14. DOI: 10.1332/263169021X161 49420135743

- Lerner J., Zbenovich C., Kaneh-Shalit T., 2021. Changing Meanings of University Teaching: The Emotionalization of Academic Culture in Russia, Israel and the US. Emotions and Society. Special Issue Emotionalization of Public Domains, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 73-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1332/26 3169021X16123454415815

- Lewis M., 2008. Self-Conscious Emotions: Embarrassment, Pride, Shame, and Guilt. Lewis M., Haviland-Jones J.M., Barrett L.F., eds. Handbook of Emotions. S.l., The Guilford Press, pp. 742-756.

- Mackenzie J.L., 2018. Sentiment and Confidence in Financial English: A Corpus Study. Russian Journal of Linguistics, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 80-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22363/2312-9182-2018-22-1-80-93

- Mackenzie J.L., Alba-Juez L., eds., 2019. Emotion in Discourse. Amsterdam, Philadelphia, John Benjamins. 397 p.

- Matsumoto D., 1989. Cultural Influences on the Perception of Emotion. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, vol. 20, iss. 1, pp. 92-105. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022189201006

- Maíz-Arévalo C., 2018. Emotional Self-Presentation on WhatsApp: Analysis of Profile Status. Russian Journal of Linguistics, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 144160. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22363/2312-9182-2018-22-1-144-160

- Musolff A., 2021. Hyperbole and Emotionalisation: Escalation of Pragmatic Effects of Proverb and Metaphor in the "Brexit" Debate. Russian Journal of Linguistics, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 628644. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22363/2687-0088-2021-25-3-628-644

- Olson R.E., Bellocchi A., Dadich A., 2020. A Post-Paradigmatic Approach to Analysing Emotions in Social Life. Emotions and Society, vol. 2, iss. 2, pp. 157-178.

- Ozyumenko VI., Larina T.V., 2021. Threat and Fear: Pragmatic Purposes of Emotionalisation in Media Discourse. Russian Journal of Linguistics, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 746-766. DOI: https://doi. org/10.22363/2687-0088-2021-25-3-746-766

- Pekrun R., 2014. Emotions and Learning. Educational Practices Series-24. UNESCO International Bureau of Education, pp. 1-32.

- Piotrovskaya L.A., Trushchelev P.N., 2020. Chto delaet tekst interesnym? Yazykovye sposoby povysheniya emotsiogennosti uchebnykh tekstov [What Makes a Text Interesting? Interest-Evoking Strategies in Expository Text from Russian School Textbooks]. Russian Journal of Linguistics, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 991-1016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22363/2687-0088-2020-24-4-991-1016

- Poggi I., D'Errico F., 2018. Feeling Offended: A Blow to Our Image and Our Social Relationships. Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 8, pp. 1-16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02221

- Scherer K.R., 1984. On the Nature and Function of Emotion: A Component Process Approach. Scherer K.R., Ekman P., eds. Approaches to Emotion. New York, Psychology Press, pp. 293-319.

- Schutz P.A., Lanehart S.L., 2002. Introduction: Emotions in Education. Educational Psychologist, vol. 37, iss. 2, pp. 67-68. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_1

- Shakhovsky V.I., 2008. Lingvisticheskaya teoriya emotsiy [Linguistic Theory of Emotions]. Moscow, Gnozis Publ. 416 p.

- Shakhovsky VI., 2009. Emotsii kak obyekt issledovaniya v lingvistike [Emotions as an Object of Research in Linguistics]. Voprosy psikholingvistiki [Journal of Psycholinguistics], no. 9, pp. 29-42.

- Shakhovsky V.I., 2015. Emotsionalnaya kommunikatsiya kak moderator modusa ekologichnosti [Ecological Compatibility Mode in Emotional Communication]. Russian Journal of Linguistics, no. 1, pp. 11-19.

- Shakhovskiy V.I., 2018. Kognitivnaya matritsa emotsionalno-kommunikativnoy lichnosti [The Cognitive Matrix of Emotional-Communicative Personality]. Russian Journal of Linguistics, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 54-79. DOI: https://doi. org/10.22363/2312-9182-2018-22-1-54-79

- Spencer-Oatey H., 2011. Conceptualising 'The Relational' in Pragmatics: Insights from Metapragmatic Emotion and (Im)politeness Comments. Journal of Pragmatics, vol. 43, iss. 14, pp. 3565-3578. DOI: https://doi. org/10.1016/j.pragma.2011.08.009

- Sutton R.E., Wheatley K.F., 2003. Teachers' Emotions and Teaching: A Review of the Literature and Directions for Future Research. Educational Psychology Review, vol. 15, iss. 4, pp. 327-358. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026131715856

- Wierzbicka A., 1999. Emotions Across Languages and Cultures: Diversity and Universals. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 362 p.

- Wierzbicka A., 2001. Sopostavlenie kultur cherez posredstvo leksiki i pragmatiki [Comparison of Cultures Through Vocabulary and Pragmatics]. Moscow, YSC. 364 p.

- Yuasa I., 2001. Politeness, Emotion, and Gender: A Sociophonetic Study of Voice Pitch Modulation. Berkeley, University of California. 160 p.

- Zappettini F., Ponton D.M., Larina T.V., 2021. Emotionalisation of Contemporary Media Discourse: A Research Agenda. Russian Journal of Linguistics, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 586-610. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.22363/2687-0088-2021-25-3-586-610