Human nature and divine essence: Ehrenberg and Rosenstock-Huessy on dogma and society in Russia and Western Europe

Автор: Kroesen O.

Журнал: Logos et Praxis @logos-et-praxis

Рубрика: Понятие человеческой природы: исторические трансформации и современные проблемы

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.23, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

In this contribution, the spiritual, theological, and social background of the changing meaning of the concept of nature is researched. It has developed within scholastic theology as part of the so-called Papal Revolution. A different understanding of the dogma leads to a different spirituality, a different societal order, and a different human self. Such is the understanding of Hans Ehrenberg and Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy. They also worked in close contact with Russian thinkers who developed a philosophy of language and society along similar lines. They were all convinced of living on the brink of a new era, an era beyond traditional church and theology, the age of the Spirit, as they stated. The great society, with its manyfold actors, is the unique event of that time, the emergence of which was brought about violently by the world wars: the world cannot be organized merely from one center. The only means of making any progress now is to open up to each other by speech! From this point of view, especially Ehrenberg and Rosenstock-Huessy have traced back the developments of church and society. An important issue in these social and historical developments is the Great Schism of 1054. Especially Ehrenberg made an attempt to understand and bring together the heritage of Russia and the heritage of Western Europe. In his vision the time has arrived that the divergence of different traditions is over. New communities of responsibility need to be created, and this requires a new understanding of grammar to counter the instrumentalization of human beings in the social machinery of production and consumption.

Hans ehrenberg, eugen rosenstock-huessy, cultural history, nature, history of religion, ethics, social and political philosophy

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149147471

IDR: 149147471 | УДК: 1:2-183 | DOI: 10.15688/lp.jvolsu.2024.3.6

Текст научной статьи Human nature and divine essence: Ehrenberg and Rosenstock-Huessy on dogma and society in Russia and Western Europe

DOI:

Both Hans Ehrenberg and Rosenstock-Huessy have dealt in depth with the divergence of the church and the society of Eastern Orthodoxy on the one hand and the CatholicProtestant church tradition and society of the West on the other. The conception of nature plays an important role in all of this. Moreover, in their particular philosophy of language, Ehrenberg and Rosenstock-Huessy charted a path to a future of mutual understanding and more, to a future possibility of inheriting each other’s precious traditions both from East and West. The work of Ehrenberg and Rosenstock-Huessy and their group of friends, the so-called Patmos Group, has remained marginal in the Western world, as elsewhere. The same has happened with their Russian conversationalists. Due to the fact that many Russian philosophers and theologians had emigrated to Leipzig, Paris, or Berlin during and after the Russian Revolution, there has also been a mutual exchange and fertilization of their points of view. In this context, they arrived at a deeper understanding of the history and development of Western and Russian societies. The changing meaning of the concept of nature is part of this development. At the same time, from their point of view, this antagonism between the West and the East is outdated because both have to deal with the new problem. The understanding of human nature needs a new starting point.

Ehrenberg and Rosenstock-Huessy – historical context

Hans Ehrenberg and Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy belonged to a group of mostly Jewish friends who, with a concerted effort, put forward an alternative to the prevailing rationalist philosophies of Kant, utilitarianism, and Hegel. The crisis of World War I had belied these philosophies, still dominant in the nineteenth century. They called themselves the Patmos group, with reference to the evangelist John, who received his Revelations while exiled to the island of Patmos. It was a group that was engaged in intense dialogue not only in lively meetings but equally through letters and later made its voice heard for three years in the journal Die Kreatur (1926–1929). The core consisted of Hans Ehrenberg and his brother Rudolf Ehrenberg, Franz Rosenzweig, of whom the aforementioned brothers were cousins, Rosenstock-Huessy, who was the great inspirer of the group, and around this core Martin Buber, Victor van Weizsäcker. For a certain period, Karl Barth was also in close contact with them. This exchange took place during and after World War I, especially in the period between 1920 and 1930, when the main fruits of their new approach were published [Ehrenberg 1923; Rosenzweig 1921; Rosenstock-Huessy 1920].

Dogma and society

Developments in theological viewpoints are always related to society. Lossky expresses this insight as follows: “If even now a political doctrine professed by the members of a party can so fashion their mentality as to produce a type of man distinguishable from other men by certain moral or physical marks, a fortiori religious dogma succeeds in transforming the very souls of those who confess it. They are men different from other men, from those who have been formed by another dogmatic conception. It is never possible to understand a spirituality if one does not take into account the dogma in which it is rooted” [Lossky 2022, 25]. This insight equals Rosenstock-Huessy’s view on society and religion. While in the early church in the East, the Empire of Constantinople was a stable factor, Western Europe, the Occident, showed the opposite. In 410, Rome was destroyed by Alaric. The shock this caused was the reason for Augustine to write his book De Civitate Dei in order to show that the city of God was not dependent on Rome for its earthly survival. According to Lossky, in this work he also laid the foundation for an unEastern, un-Orthodox understanding of the Trinity. He approached the Trinity from a general understanding of God and saw Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in a threefold relationship of self-giving love. Thus he laid the foundation for the thesis that the Spirit proceeds not only from the Father but also from the Son. Augustine laid the foundation for a bigger role for the church in the political turmoil of his time. Alaric, as well as all other Christianized tribes, was committed to Arianism, and according to this doctrine, the Son was subordinate to the Father, and in one stroke with this, the church was also subordinate to the chiefs and princes. In their territories, even independent ecclesiastical structures were created as an alternative to the Catholic Church. Only Charlemagne, following in the footsteps of his father Pepin, adopted Catholic orthodoxy as his guiding principle. The alliance with the pope helped to legitimize his rule over a multitude of tribes, over which he ruled as a Christian monarch, like a kind of David over the tribes of Israel.

Against this background, Charlemagne was anxious to be at least equal in authority and glory to the emperor of Constantinople. This policy is also expressed in his court theologians’ inclusion of the filioque in the Nicene Creed. The pope at the time did not go along with this decision and even went so far as to have the Nicene Creed placed on silver plates at the entrance to the Vatican, without the filioque. Only after the German Emperor installed a pope of his own preference in Rome in 1046 did the pope adopt the policy of Charlemagne and his chaplains in 1054. Thus the schism between East and West became a fact.

Law, scholasticism, clerics – and nature

Rosenstock-Huessy points out that in order to counteract the intertwining of church and landed gentry in the villages and of the emperor and bishops in the government at the top, the supporters of the papal revolution demanded a professional stratum of independent clerics. This was reflected in the demand for a strict celibate way of life for priests, bishops, and monks. To contain violent outbursts in the struggle between pope and emperor, both parties also resorted to the development of law. Around 1100, an independent legal faculty started in Bologna, and in 1142, Gratian published his code of law. Similarly, there was a need to bring order to the multitude of situational and contextual theological statements made by bishops, saints, and monks. Scholastic scholarship served that purpose. The method consisted simply in listing, as rationally as possible, for a given statement the arguments for and the arguments against, which resound in tradition, and drawing a conclusion. Thus a universally valid truth was constructed, which counted as a mirror of divine truth. This scholastic science was placed in the hands of the new spiritual class. The church could now effectively exercise its spatial and political authority over nobility, kings, and emperors.

In this process, the word “nature” also gradually received a different meaning than before. Physis with Plato means “planting,” and also the polis was a part of physis. The original meaning goes back to the process of life, growth [Rosenstock-Huessy 1963, 468]. Nature was increasingly perceived as dead matter – nature governed by laws and subject to them. In theology, on the other hand, the supernatural was increasingly invoked in defense against nature, so mechanistically conceived. “It became God’s nature to be supernatural” [Rosenstock-Huessy 1963, 468]. This division of nature and supernature always remained a very precarious solution, because by claiming for God the supernatural terrain, one was actually already conceding too much to the other party regarding the understanding of nature as merely dead matter. “In the spiritual realm one clings to revealed supernatural truth; in material existence one rejects, precisely because of the mechanistic worldview, the experiences evidential for revelation which rhythmic organic and living time provides” [Rosenstock-Huessy 1963, 475]. Thus the foundation was laid for a mechanistic liberal worldview in which the laws of nature themselves could act as substitutes for the general laws hitherto proclaimed by the Church in canon law. The God who during the ecclesiastical time of the Middle Ages ruled the minds by means of a generally valid theology and canon law increasingly disappeared into the background, leaving for the world an empty space where only rationalistic and utilitarian considerations reigned in accordance with a mechanistic worldview.

On the other hand, thanks to the competition between Pope and Emperor, Canon law, and universally valid theology and law, initiatives from the grassroots could emerge. By building a civil society by means of the guilds, brotherhoods, and cities, the older tribal and family relationships were pushed to the background and, by trial and error and supported and also controlled by the law, a space became available for open cooperation from the bottom up by ordinary people. A civil society came into being [Rosenstock-Huessy 1989, 148]. In this civil society, people from different tribal origins became members of guilds and cities, and as such, they treated each other as brothers and sisters, in accordance with the Lord’s word in Matthew 12: 49, 50: “These are my mother and my brothers. For everyone who does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother.” 1

Ehrenberg on Russia and the West

Ehrenberg published two volumes of texts by Russian political and historical thinkers (Vol. I) and philosophical and theological thinkers (Vol. II) in 1923 [Ehrenberg, 1923]. He has provided both volumes with an epilogue. The first epilogue deals with the Europeanization of Russia, and the epilogue to the second volume deals with the Russification of Europe. Thus, in the encounter between Russia and Europe, he asks the question of what they can learn from each other.

Since Peter the Great set out to modernize Russia, there has been an exchange between Russia and Europe. That exchange led to new political thinking in Russia during the 19th century and new philosophical/theological thinking during the 20th century [Ehrenberg 1923, vol. 1, 344]. “Russian thought therefore awakens only due to the challenge of entering into exchange with the spirit of Europe” [Ehrenberg 1923, vol. 1, 336] 2. This exchange is tense, which is why many Russian thinkers go back and forth between nationalism and theocracy on the one hand and of inheriting Europe and a new global ethic as proposed by Dostoevsky and Tolstoy on the other. It is an intellectual reorientation. Some Russian thinkers, such as Soloviev but also Dostoevsky, see the church as covert leader of the Russian state and believe – using an expression of Dostoevsky – that the state must become church. The duality of church and state and the mutual correction that goes with it has been characteristic of Europe. Eastern Europeans had no sense of this, but also many Europeans no longer have any idea (says Ehrenberg back in his days already) of the critical role of the church versus the state in earlier times. The state in the East, Ehrenberg says, has not gone through the learning school of Christianity and “surpasses the imperial cultures of the old East in despotic violence” because it makes despotism not merely a fact but even a right (Ehrenberg writes that in the time of the early Soviet Union) [Ehrenberg 1923, vol. 1, 356]. Thus, in the East, the state is the problem. In the West, it is the church. On that second issue, Ehrenberg comes to speak in his afterword to the second volume.

The Russian thinkers whom Ehrenberg addresses came to their theology and philosophy thanks to the exchange with the West, but nevertheless have their covert sources of inspiration in the Russian Orthodox Church. This Church still stands in the tradition of the ancient Church, which was replaced in the West by the Roman Catholic Church after the struggle of investiture. In her, the spirituality of the first 1,000 years is still preserved.

The Church of the East is characterized by Ehrenberg as the Johanean Church [Ehrenberg 1920, 46ff]. The Gospel and the letters of John articulate the cosmic secret of Christianity: the world is created by the Word, and Christ rules from beginning to end. This spiritual secret of world history is the one part of John’s gifts to the church. Love as self-giving love is the other part. In the West, this divine love is translated and reconfigured in canon law and in a system of social and ethical rules. In the East, this bond with Christ has never been transformed into rules and laws but therefore has remained the more spiritual. The power of the soul is present just below the surface. Berdyaev puts it this way: “There was among the Russians none of that veneration of culture which is so characteristic of Western people. Dostoevsky said we are all nihilists. I should say we Russians are either apocalyptists or nihilists. We are apocalyptists or nihilists because our energies are bent upon the end, and we have but a poor understanding of the gradualness of the historical process” [Berdyaev 1948, 128]. Earthly reality is harsh. Eastern Orthodoxy knows of a secret that is visibly hidden from the eye by a wall of separation but can therefore act on man all the more spiritually. Man is put at a distance. He sees that he has no access. His sight is limited. All the more his hearing can open to what comes from the beyond: God, who, through his love, ultimately rules the world. This is how the icononostasis works in the church, according to Hans Ehrenberg. From this spiritual source, Russian thinkers draw openly or covertly. And, at the same time, along with Western thinkers, they are nevertheless also subject to the impact of the uprooting of their traditions. It is a situation full of inner contradictions. In Russia (1923), Ehrenberg says, there is simultaneously this rootedness and this uprooting: “So much nihilism, so much shapeless humanity, so much rootedness and uprooting at the same time!” [Ehrenberg 1923, vol. 1, 367].

The lines that Ehrenberg sets out here with a tribute to Eastern Orthodox spirituality for the future are part of the age of the Spirit. In the book Heimkehr des Ketzers, Ehrenberg argues that the time of Christian churches and groups each going their own way in their one-sidedness and therefore “heresies” is over. A time of divergence is giving way to a time of convergence. In the interaction of the networks of the emerging global society, social actors are nourished by a diversity of spiritual sources. The common denominator of all these inspirations is and should be: future peace. The nourishment by these diverse religious inspirations is necessary because, without it, social actors are merely forces in space. Thus, endless collisions are inevitable. Naked forces need investiture by spiritual powers in order to create peace.

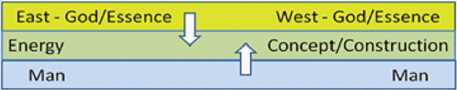

Construction and energy

Ehrenberg always puts great emphasis on the spiritual permeation of human reality by revelation in Eastern Orthodoxy. Instead of rules and procedures imposed on all and every one, the Spirit blows where it wishes. It seems that East and West offer a different solution to the mediation between God and man. This difference is related to and made necessary by the spatial task the church in the West set itself in distinction from the East, which remained time-oriented. Ehrenberg concurs with Rosenstock-Huessy’s interpretation of Western history. Human constructions, general concepts, and regulations as established in canon law become necessary and inevitable to introduce uniform governance into society. All the so-called heresies of the West can be traced back to this necessity.

The East makes the opposite move. It remains experience-oriented, so it also remains more faithful to the historical and narrative development of dogma desired by Ehrenberg. This includes his rejection of the filioque. The Spirit proceeds from the Father through the Son and incarnates in the ecclesial community that is the core of society. Thus the movement goes from God to man. This is how we come to know God in his workings throughout history: his workings, his energies. Since Palamas, the distinction between essence and energy has been widely adopted in the East. God in his essence is inaccessible to man. He dwells in an inaccessible light (I Tim. 6: 16). His workings, on the other hand, are experienced by man. The Spirit comes to us through the self-giving love of the Son, and from it we perceive the goodness of the Father (1 Corinthians 12: 4-6). Where the West attempts to draw God closer through human constructions, the East attempts to shield off God’s essence and prefers the mediation by God’s energies. Consequently, in the East, the problem of whether God’s workings of us are truly divine is often debated. 3 In the workings of God that we undergo, are we dealing with God himself, and if so, does this not lead to a duplication of God? In the West, the opposite question arises: whether human constructions really show through a mirror God himself in his innermost being, and if not so, does this not lead to a doubling of man, just as in the East there is a danger of a doubling of God (Figure)?

What is no one’s intention but imminently threatening is inevitably turned into a reality sooner or later. In the East, God disappears in his essence and in church ritual, and society remains disorganized. Thus, God and man remain separate. God’s holiness is directly opposed to a harsh society. In the West, through human construction and regulation, society is organized, but it increasingly becomes a human endeavor. Thus God finally disappears into a deistic and naturalistic faith. The system of rules that should reflect God’s goodness and love takes on a life of its own and becomes an anonymous system of rules. As a result, society becomes a machine, and man becomes a cog in it. The Europe encountered by Russian thinkers during the nineteenth century and also still at the beginning of the twentieth century is the Europe in which a mechanistic way of thinking and ethics were still dominant. In that context, it is also important to note that this mechanistic worldview based on natural laws is nothing but a secular continuation of speculative constructivist canon law and scholastic theology.

The law of technology and the grammar of language

For Rosenstock-Huessy, the counterbalance to the mechanistic worldview consists in language. For both Rosenstock-Huessy and Florenski, all language begins with the imperative. Florenski speaks of the divine I, which commandingly addresses man as You. Thus addressed, the addressed respond as We, and thus language brings about mutual understanding and a new support base for societal action. Rosenstock-Huessy sees the beginning of language likewise in the imperative mode, which is addressing man as You, and from that point onwards it is up to man to answer and say I. In dialogue, people make proposals and counter-proposals, and this is not to be understood merely as an intellectual process. People also court each other, open themselves to each other, adopt each other’s points of view, and in this way a shared concept is growing, a mutual understanding of each other, and so a We arises [Rosenstock-Huessy 1970, 45-66]. Names and stories are energies that lay claim to the powers of people, and it is up to people, listening to such a higher command, to set out a course, to respond to the imperative they hear, and in the process to become contemporaneous with each other and act.

The struggle for the right word and the sensitivity to truthful speech are practiced no longer merely in the church liturgy or in a church sermon but in the force field of society, where

Figure. Mediation between God and man in East and West

people create the world of the future. Thus begins the age of the Spirit, who speaks from the soul, which is already beyond, which already dwells at the final completion of history. The soul is already on the other side, already at the end, and we have understood the present situation only if we do not only use cause-and-effect arguments but if we understand the present situation as an intermediate step and as a preparation for the completion. From the Completion backwards, the Son draws all things towards Himself (John 12:32). This is how the Spirit works through the Son.

Conclusion: a common task for East and West

In the first half of the 20th century, living speech and the grammar of language were discovered as a source of social orientation. Both Russian and Western theologians and philosophers participated in this discovery. They saw in the emerging global society the dawn of the age of the Spirit. For Ehrenberg, especially in the book Heimkehr, this implies the necessity of a worldwide mutual (better all-sided) inheritance of each other’s traditions. For Russia and Europe, on the one hand, it implies the Russification of Europe; on the other, the Europeanization of Russia. The Russification of Europe liberates Western thought from the instrumentalization of man in the sphere of labor and from a purely rationalist/utilitarian ethic in social interaction. In the Soviet Union, scientific socialism adopted this rationalistic Western approach and applied it even more consistently. But Eastern Orthodox spirituality puts a foundation of loving selfsurrender at the bottom of our existence through the Spirit who proceeds from the Father and works among us through the Son. The time has arrived to take seriously that faithful realization of love, to be carried from the secret internal life of the Church into the public space of society. This takes place in the grammatical language theory of Rosenstock-Huessy. Thereby man is put in the position of the answering You, and in response to the appeal of love, people are led to become a We, building in mutual responsibility the society of the future. The present era with its conflicts and tensions underscores the need for this. Yet there is a consolation in the midst of all discouragement: what is needed is happening because the next outburst of the Spirit is always being prepared in secret. This is how the Spirit works.

NOTES

-

1 The aforementioned text is quoted more often in the constitution of fraternities [Rosser 2015, 59].

-

2 See also: “Being now politically integrated into Europe, in the full awakening of its political passions, Russia now enters into spiritual exchange with Europe as well” [Ehrenberg 1923. Vol. 1, 345].

-

3 Melzer points out that the German word Wirklichkeit is a word that also has Christian origins in the West, namely as originated in mysticism as a translation of the Latin actualitas . It refers to God’s workings [Melzer 1973, 52].

Список литературы Human nature and divine essence: Ehrenberg and Rosenstock-Huessy on dogma and society in Russia and Western Europe

- Berdyaev N., 1948. The Russian Idea. New York, MacMillan Publ. (Orig. 1947).

- Ehrenberg H., 1923. Östliches Christentum. Bd. I-II. Munich, Oskar Beck Publ.

- Ehrenberg H., 1920. Die Heimkehr des Ketzers – eine Wegweisung, Würzburg, Patmos Verlag.

- Lossky V, 2022. The Mystical Theology ofthe Eastern Church. Jonesville, Wellington, Crux Press. (first edition 1944).

- Melzer F., 1973. Das Licht der Welt. Ev. Stuttgart, Missionsverlag Publ.

- Rosenstock-Huessy E., 1920. Die Hochzeit des Krieges und der Revolution.

- Wurzburg, Patmos-Verlag. Rosenstock-Huessy E., 1963. Die Sprache des Menschengeschlechts, Bd. I. Heidelberg, Verlag Lambert Schneider.

- Rosenstock-Huessy E., 1970. Speech and Reality. Norwich, Vt., Argo Books Publ.

- Rosenstock-Huessy E., 1989. Die Europäischen Revolutionen und der Charakter der Nationen. Moers, Brendow (Orig. 1931).

- Rosenstock-Huessy E., 2001. Friedensbedingungen der planetarischen Gesellschaft: zur Ökonomie der Zeit. Münster, Agenda Verlag.

- Rosenzweig F., 1921. Der Stern der Erlösung. Frankfurt am Main, Kauffmann Publ.

- Rosser G., 2015. The Art of Solidarity in the Middle Ages - Guilds in England 1250-1550. Oxford, Oxford University Press.