Learning Objectives in Older Adult Digital Education - Redefining Digital Inclusion

Автор: Tomczyk Ł., Edisherashvili N.

Журнал: International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education @ijcrsee

Рубрика: Original research

Статья в выпуске: 3 vol.12, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article explores the redefinition of learning objectives within the context of digital education for older adults, addressing the critical need to enhance digital inclusion. It emphasizes the centrality of learning objectives as foundational elements in the design, implementation, and evaluation of educational programs. The study underscores the necessity of revising these objectives to promote the development of digital competences among older adults. As society becomes increasingly digitalized, traditional educational models must evolve to accommodate the dynamic digital landscape. The REMEDIS research initiative seeks to modernize educational frameworks and establish a more effective approach to cultivating digital skills in older populations. By employing SMART criteria and leveraging the expertise of senior and future trainers, the study identifies 12 key categories for contemporary educational objectives, including: basic computer and mobile device use, digital terminology, email communication, cybersecurity, online information retrieval, social media usage, instant messaging, culture and entertainment access, online financial management, e-commerce, smartphone software applications, and time management. The qualitative analysis of digital education objectives for older adults reveals a spectrum ranging from basic digital literacy to advanced e-service utilization, while also highlighting the importance of aligning these objectives with the practical needs of older adults.

Learning objectives, elderly, digital inclusion, digital skills, digital literacy

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170206555

IDR: 170206555 | УДК: 374.7-053.9:004 | DOI: 10.23947/2334-8496-2024-12-3-507-520

Текст научной статьи Learning Objectives in Older Adult Digital Education - Redefining Digital Inclusion

Learning objectives form the basis for the planning, implementation, and evaluation of every process of formal and non-formal education ( Kupisiewicz, 2012 ). Didactic objectives set the direction of the activities undertaken by students and teachers and are linked to educational forms, methods, and content. The creation of learning objectives is the first step in shaping educational programmes regardless of the age group, subject area, or organisational form of education. Without appropriately defined didactic objectives, it is impossible to achieve goals that build the ability to function in the modern world ( Lemieux, 1997 ; Baschiera, 2017 ; Tomczyk et al., 2023 ). Therefore, when designing activities for older adults, attention is increasingly being paid to locating learning objectives in real conditions relating to the specifics of the target demographic ( Szarota, 2004 ; Tomczyk, 2015 ), as well as taking into account their needs - in the case of this article, people in late adulthood. The focus of this paper is on redefining the learning objectives related to digital education for senior citizens. Several issues prompted the creation of this article. Firstly, the literature lacks a clear and –commonly-agreed classification of learning objectives relating to digital inclusion ( Beh et al., 2018 ; Choudhary, 2024 ). Secondly, the process of setting didactic objectives that take into account the specificity of older adults’ needs is now seen as a pressing requirement due to the professionalisation of education in institutions dedicated to this group (e.g. universities of the third age, seniors’ clubs, organisations supporting community activation) ( Mackowicz and Wnek-Gozdek, 2016 ). Finally, due to the intensive development of the information society, there is a need to redefine the

© 2024 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license .

didactic goals and thus the content of education due to the increase in opportunities currently offered by cyberspace (e.g. the intensive development of AI, the increase in the speed of Internet connections, the digitalisation of administration and healthcare, and e-commerce) ( Ziemba, 2019 ). Such rapid and irreversible changes require an analysis to be undertaken on the establishment of universal and variable didactic objectives that set the directions for the digital inclusion of this socially important group.

Learning goals guide the implementation of any educational programme. Learning goals define the areas of activity to be carried out by learners and condition the selection of learning content, learning resources, and forms of learning. The selection of learning objectives in the process of digital inclusion determines the results in terms of the level of participation of individual age groups in the information society ( Zdjelar and Žajdela Hrustek, 2021 ). Educational goals and content therefore have a not insignificant impact on proficiency in the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs), as well as on attitudes towards new media ( Lam and Lee, 2006 ), the level of techno-stress ( Akyıldız Munusturlar and Hastürk, 2023 ; Salo et al., 2022 ), and the enhancement or reduction of self-motivation to learn about the possibilities offered by cyberspace ( Stojić, 2017 ). Appropriately planned learning objectives, i.e. selected according to the needs of the target group, timeliness, and relevance, provide an opportunity to reduce the level of digital exclusion and thus professionalise the education process of senior citizens in the area of new media use ( Zadražilová and Vizváry, 2021 ; Koppel and Langer, 2020 ).

Why is there now a need to redefine the aims of new media geragogy education? One answer can be found in the data for the 27 member states of the European Union, which shows that only one in four people aged 65 to 74 has at least basic digital skills ( European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2023 ). The latest EUROSTAT data show that the largest share of this group (more than 30%) is made up of people whose digital competences could not be assessed because they have not used the internet in the last 3 months. About 10% of the group possess no digital competences at all. 20% of this group have limited digital competences, meaning that only two of the five indicators were assessed at a basic level or higher. A small percentage (around 5%) have narrow digital competence, where three of the five indicators are at basic level or above. A negligible percentage (less than 5%) show low digital competence (four out of the five indicators at basic level). Less than 10 per cent of this age group reaches the basic level, where all indicators are assessed at basic level or above ( Eurostat, 2024 ). At the same time, it is important to be aware that EUROSTAT data do not include senior groups aged 75 and over, where the rates of systematic use of new media, as well as the level of digital and media literacy, are at a lower level than their counterparts in the 65-74 age category. The scale of digital exclusion in Europe is one of the main arguments in favour of the need to redefine models of educational inclusion, as well as to strengthen the non-formal education sector aimed at senior citizens.

Digital education for seniors is characterised by a high level of voluntarism in the choice of learning objectives and content as evidenced, among other things, by the multiplicity and diversity of typologies in this field. In this regard, it is worth considering some of the current methodological frameworks to highlight how greatly the approaches concerning the digital inclusion process for older people vary. One popular standard aimed at older people is ICDL (ECDL) E-Citizen ( Inceoglu, 2005 ; Tattersall et al., 2006 ). The approach proposed by the International Computer Driving Licence at E-Citizen level implies that learning objectives should include: operation of a computer and simple programs (e.g. starting, working in the operating system, creating files and folders, saving data), the basics of the Internet (e.g. using a web browser), the basics of Internet mail (e.g. understanding relevant e-mail, using one’s own e-mail account efficiently), searching for information (e.g. using the right keywords, copying information from websites), and handling online services (using various e-services to meet the needs of daily life) ( Leahy and Dolan, 2010 ; Tristán-López and Ylizaliturri-Salcedo, 2014 ). The ICDL E-Citizen standard delineates the very elementary areas of digital competence that contemporary users should have to make basic use of the possibilities of cyberspace. E-Citizen has also become the basis in many countries for government programmes that focus on minimising digital exclusion among groups with digital deficits. It is also worth mentioning that this standard makes it possible to obtain certificates that provide official confirmation of this key competence.

The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp) presents a nuanced approach to defining learning objectives. The latest iteration, DigComp 2.2, delineates five principal domains of digital competence, further subdivided into 21 specific categories, each serving as a scaffold for indicators of digital competence (Vuorikari et al., 2022). DigComp 2.2 encompasses the following domains: “(1) Infor- mation and Data Literacy (including browsing, searching for, and filtering data, evaluating data and digital content, and managing information), (2) Communication and Collaboration (covering interaction, sharing, civic engagement, collaboration, netiquette, and digital identity management through digital technologies), (3) Digital Content Creation (encompassing digital content development, content integration, copyright and licensing, and programming), (4) Safety (focusing on device protection, data and privacy protection, health and well-being, and environmental protection), and (5) Problem Solving (including technical problem-solving, identifying technological needs and responses, creatively applying digital technologies, and recognizing gaps in digital competence)”.

Crucially, DigComp 2.2 is designed to facilitate the adaptation of learning objectives and content based on the proficiency levels of different learner groups, with the specification of eight levels of advancement. However, not all the domains within this framework are optimally aligned with the learning needs of senior citizens. This population often requires tailored approaches due to the unique challenges associated with digital inclusion and the distinct needs that new media can fulfill in their lives.

In examining digital and media competences suitable for users of contemporary ICT—particularly senior citizens—the Media and Information Literate (MIL) Citizens Framework developed by UNESCO (2021) provides a valuable reference. This model emphasizes the cultivation of interrelated knowledge and skills across several key areas: “(1) Understanding the Role of Information, Media, and Digital Communications in Sustainable Development and Democracy, (2) Understanding Content and its Uses, (3) Accessing Information Effectively with Ethical Practice, (4) Critically Evaluating Information, Sources, and Ethics, (5) Applying Digital and Traditional Media Formats, (6) Situating Information, Media, and Digital Content in Sociocultural Contexts, and (7) Promoting Media and Information Literacy (MIL) among Learn-ers/Citizens and Managing Required Changes”.

The UNESCO framework offers a comprehensive approach to delineating educational objectives that enhance individuals’ abilities to acquire, interpret, and process information. This model places a strong emphasis on the pivotal role that information circulation and reception play in everyday life. Nonetheless, as with DigComp 2.2, the MIL framework is extensive and may not fully align with the specific needs of older adults. Implementing these typologies within educational practice can present challenges, owing not only to their complexity but also to the necessity of developing solutions grounded in practical, community-based needs.

Recognizing the need for targeted pedagogical support for educators working with digitally marginalized groups, along with insights from recent research networks aimed at optimizing educational practices ( Martinez et al., 2023 ; Vissenberg et al., 2023 ), a decision was made to conduct localized research. This research seeks to refine learning objectives, with a particular focus on the digital and media competences pertinent to older adults.

Methodology

Aim and subject of the research

The aim of the research is to redefine the didactic objectives related to the formation of digital competences among senior citizens. The objective stems from the need to modernise the educational framework in institutions that deal with the digital inclusion of people in late adulthood. The objective is also linked to the dynamic transformation of the information society, which has an impact on the reshaping of learning objectives and therefore on the definition of the process of digital inclusion. The research objective was also determined by the implementation of the international project REMEDIS - Redefining Media Literacy and Digital Literacy in Europe, which was supported by the National Science Centre. The activities carried out as part of the project not only had the character of a diagnosis of the components of the didactic framework determining the directions of digital education of older adults, but also represent a possible practical guideline for trainers and educators of older people. The research objective took the form of the following question - what elements should currently the theoretical framework comprise that defines didactic goals in the process of effective digital inclusion? The subject for the question thus posed was the responses of experts, trainers, and potential educators of older people participating in the online course ‘How to effectively teach older adults how to use new media’.

Research procedure

The research was conducted using the Open UJ online platform, which hosted an online course related to the methodology of effective digital inclusion. The course was based on the model of digital inclusion developed by the Polish research team of the REMEDIS project ( Tomczyk, 2015 ) covering modules related to the preparation, implementation, and evaluation of the effectiveness of non-formal education addressed to older adults. The course ‘How to effectively teach older adults how to use new media’ in its structure included a number of problem tasks for the students, which covered different stages of activities relating to digital inclusion. One of the tasks, based on the PBL methodology, concerned the development of an up-to-date and relevant selection of learning objectives relating to the formation of digital and media competences. Course participants thus not only improved their knowledge of senior education methodology, but also participated in a research process that made it possible to redefine learning objectives using the knowledge they had gathered. This activity provided an opportunity to harness the potential of the cumulative wisdom of the trainers, future trainers, and people interested in the topic of digital inclusion. The course was conducted between February 2024 and September 2024 and the research generated 66 responses that met the data validity criteria. The definition of the learning objectives was based on SMART assumptions, so responses were checked against the following requirements: (1) specificity; (2) measurability; (3) achievability; (4) realism; and (5) timeliness ( Do et al., 2024 ). The data collected were subjected to content analysis using grounded theory ( Strauss and Corbin, 1990 ; Krippendorff, 2019 ). The content analysis involved reading all the participants’ statements several times and discarding statements that were not related to the research problem (though none of the responses fell under this category). Subsequently, the participants’ statements were categorised, i.e. logically separate areas defining the learning objectives emerged. The process of creating a new category took place in the absence of a learning area relevant to the respondent’s statement. The categories were illustrated through the sample statements of the course participants. The process of analysis and categorisation was carried out by one expert, while the final result in the form of a ready-made map of learning goal categories was evaluated by two external researchers working in the field of digital inclusion. The entire research procedure is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Research procedure: collection, analysis, categorisation of data

OVERALL IMPRESSION -FIRST READING OF THE DATA

ANOTHER CODING OF

ANALYSIS OFTHE STATEMENTS

DATA -RE-READING

CREATING CATEGORIES OF LEARNING OBJECTIVES IN THE PROCESS OF DIGITAL INCLUSION

EXTERNAL CATEGORY CONTROL BY TWO EXPERTS

THE DATA COLLECTION PROCESS IN AN ONLINE COURSE

HOW TO EFFECTIVELY TEACH OLDER PEOPLE HOWTO USE NEW MEDIA?

SEPARATION OF QUALITATIVE DATA ON THE OPENUJ PLATFORM

Research ethics

The research was carried out with due consideration of the ethics of social science research. The respondents’ answers were stripped of any data that could lead to personal identification. The data were collected in anonymous form (using the MOOC platform). The purpose of the research and the methods of data processing were presented to the respondents, who were also informed that they could opt out of the research at any time. The entire procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Leuven - approval number REMEDIS - G-2022-6106-R2(MAR).

Findings

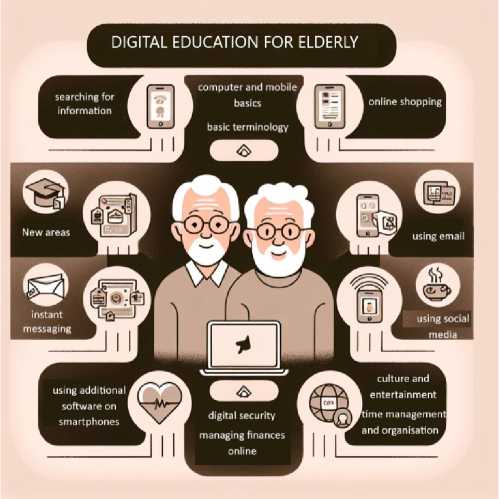

Based on the analysis and categorisation of the responses, 12 main learning objectives were identified. The learning objectives indicated should be considered separately in some situations (e.g. basics of computer and mobile device use, use of basic digital terminology) and thus depending on the stage of learning to use new media reached by the student. Conversely, some objectives overlap with other areas (e.g. use of email, digital safety). Thus, at a secondary level, the achievement of one learning objective enables the achievement of further learning objectives (e.g. use of e-banking, social networks). The 12 learning goals presented in Figure 12 should be categorised as general goals, which, depending on the circumstances (e.g. specific features of the computer lab, size of the group, needs of older adults), are used to set specific goals that include available and appropriate hardware and software resources. A summary of the categories is presented in Graphic 2.

Figure 2 Goals of digital education for seniors

Source: Developed using the Co-Pilot tool

Results

Computer and mobile basics

When setting the learning objectives for digital education, the respondents first pay attention to issues relating to the basics of using ICT. The respondents are aware that the ability to switch a device on and off, to open and close a piece of software, and to understand the functioning of the graphic user interface are prerequisites for the efficient use of new media. The objectives listed in the statements below are a boundary condition for further objectives.

‘To teach how to use the basic functions of a computer and smartphone: learning to start and shut down the device, learning to use the keyboard and mouse or the touchscreen’.

‘Participants will be able to operate the computer and mobile devices in terms of basic functions, such as starting up, shutting down, opening programs, etc.’

The basics of operating a computer and mobile devices is a target defined for people who are completely digitally excluded and therefore have no previous exposure to ICT. All later stages of ICT education rely on the skills acquired here.

Basic terminology in the digital world

Directly linked to the above category is another set of objectives related to the ability to use basic terminology. The use of ICT necessitates an expansion of the lexical stock to include terms related to IT equipment, the Internet, and websites. In the initial stage of digital inclusion, this process is very intensive if only because of the complexity of the activities taking place in cyberspace or the phased inclusion of more and more new e-services requiring the expansion of basic terminology.

‘Understanding basic terms related to computers, internet and software.’

‘Participants will be able to list and explain key digital terms.’

To the above objectives, one respondent adds the valuable idea of linking terminology to specific activities.

‘Provide clear definitions and examples for each concept in the form of presentations and practical exercises.’

In the process of forming media and digital competence, building a good knowledge of the most common language used in ICT is an essential early step. However, this fact seems to be overlooked in many educational programmes and often appears only to be included as a tangential feature in training older adults to use hardware and software and to navigate the operating system of their device.

Using e-mail

Among the basic learning objectives, the respondents highlight another elementary issue, which is the ability to use e-mail. Today, having one’s own e-mail account is a boundary condition for using other e-services (e.g. shopping, logging in to e-services). Without the ability to log in to email, receive and send emails, or send attachments, the use of cyberspace is severely limited.

‘Teaching the use of e-mail: preparing, sending and receiving e-mails, adding attachments to messages’.

‘Practical exercises on preparing, sending and receiving emails, as well as education on securing an email account.’

‘Teach senior citizens to use basic online communication tools such as email and chat rooms.’

Using email is one of the elementary goals of digital education for older adults. This objective can be broken down into several operational objectives related to email use. The realisation of this objective starts with setting up an e-mail account and then shaping the login and logout process. In the next stage of the process, more elaborate possibilities related to the effective use of email come into play.

Digital security

One of the overarching goals of digital education is to ensure the safety and security of ICT users. The ability to protect one’s own data and to secure devices and software against malware and similar negative phenomena is one of the basic components of digital literacy. The ability to anticipate negative phenomena is now a starting point in the use of the Internet being universal for all e-services.

‘Ensuring awareness of risk and safe use of the Internet: identifying potential risks such as online fraud.’

‘Increasing digital safety awareness: Educating senior citizens about online threats such as phishing, malware and online scams.’

Digital safety is an elaborate learning objective consisting of a number of specific objectives defined by the level of digital and media competence. This overall learning objective is found in combination with other objectives and co-occurs at almost every stage of the digital inclusion process. Given the increase in the number and complexity of risks, this objective should be implemented throughout the learning and teaching process for senior citizens, starting with simple activities (e.g. logging into an e-mail account or SNS) and moving on to more complex activities such as e-banking and e-shopping.

Searching for information on the Internet

Among the other learning objectives included in the foundations of digital education is information retrieval. This general objective is essential for meeting the needs of seniors and is pursued along with learning the basics of the Internet. Information retrieval is an activity that can be carried out using a variety of online tools and provides an opportunity for trainers to design a range of teaching forms using diversified forms of information access.

‘Searching for information using search engines’.

‘Seniors will be able to use search engines, read online news and browse websites’.

Information search as a general learning objective can have specific objectives in the form of shaping seniors’ ability to use simple search engines as well as more advanced e-services, such as scientific repositories, newsgroups, AI-based tools. Searching for information is therefore a general objective that, like digital security, can be developed depending on the level of proficiency in using ICT.

Use of social media

The use of social media is now considered a basic activity for obtaining information and communicating with the wider world, as well as for disseminating private and professional information. Social networking sites (SNS) are a natural channel for socialisation and communication among the younger generations, though in many cases they represent terra incognita for older generations. According to the respondents, however, this area should be one of the main objectives of digital education, though access to and use of SNS should be done safely and securely, with this showing the interpenetration of educational goals.

‘Teaching the use of social media: creating an account on social media platforms, posting, sharing content and commenting’.

‘Organising interactive sessions where senior citizens can practice the principles of safe social media use’

‘Teaching senior citizens how to use the most popular apps to keep in touch with loved ones - facebook, messenger, whatsapp, skype’

The use of SNS is now an extension of the basic or previous forms of communication in cyberspace, such as chat programs and email. The objective presented is achievable with the previously mentioned skills related to ICT basics. SNS, despite being multimedia and thus a relatively intuitive e-service, require a broader knowledge of online profiles and online information sharing mechanisms, as well as awareness of information persistence in SNS, identity theft, manipulation in SNS, self-creation through SNS, and other aspects. It is therefore suggested that this objective should be pursued following on from the attainment of baseline digital and media competences and linked to the needs of older people.

Using instant messaging

One of the natural needs of senior citizens is to communicate with loved ones. This area was noted in the respondents’ statements in the form of an objective defined as the ability to select and use an instant messenger. This objective can be met by a diverse range of communicators and should be selected based on a realistic diagnosis of the popularity of individual applications. In other words, the transfer of this didactic objective into educational content should be characterised by the highest level of praxeology.

‘Teaching senior citizens to use instant messaging: Senior citizens will be able to recognise different applications for communication’.

‘Teaching senior citizens to use the most popular applications with which they can contact their loved ones - messenger, whatsapp, skype’

The ability to use instant messaging is now counted among the basics of ICT use. This objective also provides an incentive for many older adults to undertake educational activities, not least because of the rapid transfer of many communication processes in a mediated manner through free digital tools.

Culture and entertainment

Among the general objectives of digital education, the respondents highlighted the important category of cultural participation and the ludic aspect mediated by ICT. The responses in this area combine the needs of everyday life with the opportunities that cyberspace now offers. The goal of using entertainment resources is achievable at different levels of sophistication, and at a variety of cost points, starting at zero.

‘Broadening the cultural perspective to include the online space. To familiarise senior citizens with the digital potential in this area. Movies, series, ebooks, online magazines’.

‘Senior citizens become acquainted with new sites, applications, software that broaden their knowledge on topics of interest’.

‘Thanks to new sites, the older adult comes into contact with people sharing similar interests’

This area is universal and fits the needs of almost every senior citizen. The ludic dimension of ICT use is an activity that applies not only to computers but also to mobile devices and can be used with the Bring Your Own Device - BYOD concept in mind.

Online financial management

Among the general objectives, there is the question of forming skills and knowledge related to the use of e-banking. This objective overrides other ICT mediated skills, e.g. online payments, online shopping, and admission reservations. Today’s stage of development of the information society makes this skill a prerequisite for the full use of e-services.

‘Log in to a bank account online and check the balance and transaction history’.

‘Master the use of a banking application’.

Managing online finances is a natural issue for digital natives, while for digital immigrants it can be a limitation due to a lack of trust in new technologies, fear of being scammed, and inadequate levels of basic digital competences related to cyber security.

Online shopping

Some objectives build inextricably from others; online shopping is only truly feasible if the user is acquainted with the demands of electronic banking. The respondents suggest that here, as in other cases, it is important for topics to progress according to the logic both of increasing difficulty or complexity, and increasing need for fundamental competences.

‘Online shopping nowadays is not only an option but sometimes a necessity’.

‘Presenting the benefits of using online shops’.

‘Teaching seniors how to use online shops on their own, positively influencing the reception of courses teaching modern technology’

‘Replacing visits and queues at the shop for using convenient applications in the comfort of the home’

According to the respondents, using e-commerce is not only about shaping the ability to find a product online and to purchase it, but also about forming attitudes related to paying attention to the benefits of this activity. Online shopping skills as a goal of digital education can also be implemented to a limited extent without the use of online payments (especially for senior citizens with high levels of anxiety) with the use of cash on delivery, or collecting the order in a bricks-and-mortar shop.

Use of additional software on smartphones

Today’s information society is characterised by a high degree of smartphone use. These devices allow simple communication needs to be met as well as enabling a range of other activities to be performed. The respondents highlight the need for digital education not only in terms of using these devices by making calls and receiving text messages, but above all in terms of being able to install additional software to extend the functionality of the smartphone.

‘Learning about basic mobile applications: installing and updating applications’.

‘Acquisition of smartphone skills by senior citizens in the area of at least 10 applications within 2 months’.

Paying attention to extending the functionality of smartphones is an important element in creating modern and relevant digital education goals for senior citizens. Having the ability to install additional software – as well as knowing that this is possible to begin with - significantly expands the possibilities of the smartphone, enabling increased independence for the user and opportunities for older people to function in today’s information society. However, it is important to be aware that this area requires the possession of basic smartphone skills (core competences), as well as proficient use of e-mail, as well as the ability to assess the usefulness of potential software available in external repositories.

Time management and organisation

According to the respondents, it is worthwhile for senior citizens to expand their field of activity using ICT to include online calendars. This objective is linked to online communication and also allows for the improved organisation of daily life.

‘Participants will be able to use the basic functions of applications such as calendars and instant messaging’.

‘Participants will be able to transfer money online and make appointments using an online calendar.’

As with the other objectives presented in the empirical section, it should be noted that the use of this category of software requires basic digital competence. In the case of time management and organisation, senior citizens should have developed other skills beforehand, such as the use of email, the ability to log in or use instant messaging - if meetings are to be planned and carried out online.

Discussion

The redefinition of digital and media competences is now a necessity due to the rapidly developing information society ( Webster, 2014 ), which is transforming the catalogue of requisite knowledge and skills related to the use of ICT ( Novković Cvetković et al., 2018 ). Permanent changes caused by the dynamic development of e-services and the possibilities of access to devices (e.g. smartphones, tablets) force a reflection on current and adequate indicators of knowledge and skills in handling new media ( Tomczyk, 2024 ). The revision of new media literacy curricula applies to both formal education and non-formal education ( D’Ambrosio and Boriati, 2023 ; Korpela et al., 2023 ). One example of the intensive changes taking place in the aims, content, and forms of education is digital education for senior citizens ( Vercruyssen et al., 2023 ). It is senior citizens who are still one of the most digitally excluded social groups ( Tomczyk et al., 2023 ); this demographic requires special attention due to the slow transformations associated with the intensity and uses of ICTs ( Quialheiro et al., 2023 ; Martínez-Alcalá et al., 2019 ). The conditions described in the empirical section due to the rapid technological changes and the still unsatisfactory use of ICT in this age group force the question of the effectiveness of digital education.

One of the determinants of the effectiveness of contemporary digital inclusion is the selection of appropriate educational goals. Based on the opinions of people interested in the topic of digital inclusion, the trainers and future trainers identified 12 main goals of contemporary digital education for senior citizens. These objectives coincide with existing frameworks for the development of digital competences ( Vuorikari et al., 2016 ; Caena and Redecker, 2019 ; Hammoda and Foli, 2024 ), so are themselves an extension of existing approaches to the translation of theoretical assumptions into practice ( Kluzer and Priego, 2018 ). The differentiating factor of the 12 areas and their principal learning objectives presented in this article is that it looks at the process of building digital competences by narrowing the analysis to the group of oldest ICT users, which is not obvious for a general framework of digital competences. Secondly, the proposed model is based on the accumulated knowledge of experts dealing with the topic of digital learning for senior citizens from the perspective of bottom-up activities. Thirdly, the objectives outlined can serve as a practical reference point for building original educational programmes implemented in Universities of the Third Age, seniors’ clubs, and other institutions that operate bottom-up, without direct reference to elaborate strategies and documents (e.g. the European Digital Competence Framework).

Based on the responses, 12 main learning objectives were identified, which include both the basics of ICT use (computers, smart phones, Internet services), as well as more advanced skills that require the achievement of previous objectives. As an example of how competences increase in complexity or difficulty of acquisition (Szarota, 2004; Luppi, 2009), there are objectives related to the basics of using computers and mobile devices, the formation of basic terminology concerning the digital world, and the use of e-mail. These three learning objectives now form the basis for effective use of the opportunities offered by cyberspace. Mastering the basic vocabulary of hardware and software is the starting point for further, more complex activities. However, it should be emphasised that these activities are not only carried out at a basic level, as the reinforcement of lexical resources concerning new media is also built up as older adults encounter the use of any new software or hardware. Among the basic learning objectives that remain relevant throughout is the use of email (Sanecka, 2014). This skill is counted as an elementary objective since it is impossible to achieve advanced digital and media competences without the ability to log in to email, receive and send email, and add and forward attachments via email (Tomczyk, 2015).

The respondents also identified digital safety as one of the core categories. This area forms the basis of competence in using new technologies regardless of the metric age of e-service users ( Guillén- Gámez et al., 2024 ). Digital security is a goal that should be achievable while learning about the specifics of each e-service. However, it should be added that, in the case of senior citizens, too much focus on this objective alone may lead to the cultivation of fears that may prove counter-productive to the assumptions that characterise the digital inclusion process.

Another category of objectives identified by the trainers was searching for information on the Internet. This goal is one of the basic activities in all age groups, but in the case of senior citizens it takes on particular importance due to the specific type of needs, e.g. health, economic, that new media can satisfy ( Sayago and Blat, 2007 ; Jung et al., 2011 ). Information retrieval takes on a new meaning when the possibilities offered by generative artificial intelligence are taken into account ( Qian et al., 2021 ; Czaja and Ceruso, 2022 ). This area in relation to the digital and media competences of senior citizens is wholly new territory and represents a new dimension of competence that trainers of older adults should take into account when planning programmes.

Another important area in the goal of digital education for senior citizens is online communication. Contact with others can be mediated through social networks as well as instant messaging. Both solutions are typical for the younger generation of ICT users and are not primarily associated with senior citizens ( Maier et al., 2011 ; Nef et al., 2013 ). Nevertheless, from the perspective of the trainers of older people, the inclusion of this area in digital education becomes essential due to the communication possibilities these approaches represent, and also because of the wish to confer access to the specific type of information that social networks and instant messaging offer. This area also appears to be extremely important from the perspective of enhancing senior citizens’ cost-free communication with loved ones.

Among the goals of digital education, the respondents also highlighted culture and entertainment. The Internet can enable fast and free access to ludic digital content ( Hilt and Lipschultz, 2004 ). Thanks to the development of video on demand technology and the proliferation of online magazines and digital books, many new possibilities for entertainment are open to users with the appropriate competences – thus making this an important area in the development of educational programs for older adults.

More advanced uses include online financial management and online shopping. Due to the growing older population and changes in attitudes towards treating senior citizens as valuable customers (the so-called silver economy), this area of digital competence seems extremely promising, as has already been highlighted many times in non-educational publications ( Haiteng et al., 2021 ; Ganguly et al., 2024 ). However, the digital education of older adults regarding the e-commerce area requires the formation of basic digital competences, as well as knowledge of security, ensuring that senior citizens are protected from dishonest sellers or the hacking of their online accounts.

An advanced goal of digital education for senior citizens is also to extend the capabilities of their smartphones by installing additional software. Older adults are the group with the lowest level of digital competence ( Vidal, 2019 ; Jeong and Bae, 2022 ), so this goal should be classified as ambitious but possible and necessary to achieve given the potential offered by the devices. The use of additional software by senior citizens also shatters the myth that not all possibilities of the modern digital world are available to older adults.

Among the atypical, and therefore less common goals of digital education is the inclusion of aspects related to learning software for time management and organisation of personal activities. This activity is primarily intended to foster the free-time activities of senior citizens and encourage the use of solutions popular with other age groups.

Conclusions

The study focused on twelve essential domains crucial for the skills development of older adults, differentiating between basic and advanced layers of skills. General skills in digital tools such as using personal computers and mobile devices, a knowledge of basic digital vocabulary, and emailing are examples of primary competences. There must be a focus on these skills as they lay the groundwork for interacting with digital tools and platforms. Among other things, senior citizens who do not know how to use email will struggle because many aspects of online services require creating accounts or communicating through e-mail. In contrast, advanced competences involve skills that might include online banking and business transactions as well as the appropriate use of social media tools. Though these much more advanced skills have significant benefits, the real-world relevance to older adults needs to be considered. Focusing too much on complicated activities—such as running complex online banking systems or learning the many features of social media—can lead to frustration and hence demotivation. Digital literacy programs, therefore, need to prioritize skills that have a meaningful and positive impact on participants’ existing abilities and daily routines.

How educational content is organized and what is focused on is just as critical. Ensuring a gradual approach is thus very important. Programs should proceed step by step, starting from the fundamentals and then moving onto more complicated topics so as to avoid overburdening older adults who may feel overwhelmed with learning new digital skills. A supportive learning environment is needed, one that respects where individuals start and that develops them at their own pace to become confident and competent in using digital technologies effectively.

These results show that what is urgently needed is a prompt re-conceptualization of how digital literacy initiatives for older adults are developed. Holistic programs tailored to the needs of this age group will have positive impacts on individual well-being and social inclusion. In these ways, efforts that empower older adults to participate in a digitally active society not only reduce disparities in basic digital skills but also contribute to social cohesion. These require clear, practical learning objectives and the use of adaptive teaching methods that respond to the diverse needs of older learners.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This article was written as part of the REMEDIS project, which is supported in Poland by the National Science Centre - NCN [2021/03/Y/HS6/00275] under the CHANSE ERA-NET Co-fund, awarded funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme [contract number 101004509].

Author Contributions

Łukasz Tomczyk: conceptualization, methodology, data collecting, writing – original draft, formal analysis, writing – review and editing. Natalia Edisherashvili: abstract, review, editing and conclusions.

Список литературы Learning Objectives in Older Adult Digital Education - Redefining Digital Inclusion

- Akyıldız Munusturlar, M., & Hastürk, G. (2023). Technostress in older onliners: a scale adaptation study. Educational Gerontology, 49(9), 817-829. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2022.2164657 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2022.2164657

- Baschiera, B. (2017). Key competencies in late-life learning: Toward a geragogical curriculum. Innovation in Aging, 1(suppl_1), 1356–1356. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx004.4984 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx004.4984

- Beh, J., Pedell, S., & Mascitelli, B. (2018). Achieving digital inclusion of older adults through interest-driven curriculums. The Journal of Community Informatics, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.15353/joci.v14i1.3403 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15353/joci.v14i1.3403

- Caena, F., & Redecker, C. (2019). Aligning teacher competence frameworks to 21st century challenges: The case for the European Digital Competence Framework for Educators (Digcompedu). European journal of education, 54(3), 356-369. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12345 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12345

- Choudhary, H. (2024). Building bridges to digital inclusion: implications for curriculum development of digital literacy training programs. International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning, 16(3), 282-296. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTEL.2024.139706 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTEL.2024.139706

- Czaja, S. J., & Ceruso, M. (2022). The promise of artificial intelligence in supporting an aging population. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making, 16(4), 182-193. https://doi.org/10.1177/15553434221129914 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/15553434221129914

- D’Ambrosio, M., & Boriati, D. (2023). Digital Literacy, Technology Education and Lifelong Learning for Elderly: Towards Policies for a Digital Social Innovation Welfare. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 15/2 21-36. https://doi.org/10.14658/PUPJ-IJSE-2023-2-2

- Do, N. X. B., An, T. S., & Krauss, C. (2024). SMART-Goal-Buddy: Goal-Setting Oriented Adaptive Learning Paths. In International Workshop on Learning Technology for Education Challenges (pp. 319-331). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-61678-5_23 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-61678-5_23

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2023). Fundamental rights of older people: ensuring access to public services in digital societies. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Eurostat (2024). Digital skill level by age group 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Figure2_digital-skills-age-groups_updated.png

- Ganguly, B., Nag, T., & Chakraborty, P. (2024). Did Covid-19 influence adoption of e-commerce among elderly citizens? The role of social presence, self-efficacy and trust. International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development, 18(1-2), 30-44. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJISD.2024.135228 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1504/IJISD.2024.135228

- Guillén-Gámez, F. D., Tomczyk, Ł., Ruiz-Palmero, J., & Connolly, C. (2024). Digital security in educational contexts: digital competence and challenges for good practice. Computers in the Schools, 41(3), 257-262. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380569.2024.2390319 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/07380569.2024.2390319

- Haiteng, Z., Longteng, L., Lei, Y., Silin, L., & Kaili, Z. (2021). Modeling and Analysis of Group Consumption Behavior of the Elderly under the Background of E-commerce. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Electronic Technology, Communication and Information (ICETCI), 598-602. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICETCI53161.2021.9563457 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/ICETCI53161.2021.9563457

- Hammoda, B., & Foli, S. (2024). A digital competence framework for learners (DCFL): A conceptual framework for digital literacy. Knowledge Management & E-Learning, 16(3). https://doi.org/10.34105/j.kmel.2024.16.022 DOI: https://doi.org/10.34105/j.kmel.2024.16.022

- Hilt, M. L., & Lipschultz, J. H. (2004). Elderly Americans and the Internet: E-mail, TV news, information and entertainment websites. Educational Gerontology, 30(1), 57-72. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270490249166 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270490249166

- Inceoglu, M. M. (2005, May). International standards based information technology courses: A case study from Turkey. In International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications (pp. 56-61). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/11424925_7 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/11424925_7

- Jeong, J. H., & Bae, S. M. (2022). The relationship between types of smartphone use, digital literacy, and smartphone addiction in the elderly. Psychiatry Investigation, 19(10), 832. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2021.0400 DOI: https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2021.0400

- Jung, W. S., Kang, H. G., Suk, M. H., & Kim, E. H. (2011). The use of the internet health information for the elderly. Journal of Korean Public Health Nursing, 25(1), 48-60. https://doi.org/10.5932/JKPHN.2011.25.1.048

- Kluzer, S., & Priego, L. P. (2018). DigComp into Action: Get inspired, make it happen. A user guide to the European Digital Competence Framework (No. JRC110624). Joint Research Centre. https://doi.org/10.2760/112945

- Koppel, I., & Langer, S. (2020). Basic digital literacy-Requirements and elements. Revista Práxis Educacional, 16(42), 326-347. https://doi.org/10.22481/praxisedu.v16i42.7354 DOI: https://doi.org/10.22481/praxisedu.v16i42.7354

- Korpela, V., Pajula, L., & Hänninen, R. (2023). Older Adults Learning Digital Skills Together: Peer Tutors’ Perspectives on Non-Formal Digital Support. Media and Communication, 11(3), 53-62. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i3.6742 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i3.6742

- Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071878781 DOI: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071878781

- Kupisiewicz, C. (2012). Dydaktyka. Kraków: Oficyna Wydawnicza Impuls.

- Lam, J. C., & Lee, M. K. (2006). Digital inclusiveness--Longitudinal study of Internet adoption by older adults. Journal of Management Information Systems, 22(4), 177-206. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222220407 DOI: https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222220407

- Leahy, D., & Dolan, D. (2010, September). Digital literacy: A vital competence for 2010?. In IFIP international conference on key competencies in the knowledge society (pp. 210-221). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-15378-5_21 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-15378-5_21

- Lemieux, A. (1997). Essential learning contents in the curriculum for a Certificate Degree in Personalized Education for Older Adults. Educational Gerontology: An International Quarterly, 23(2), 143-150. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/0360127970230205

- Luppi, E. (2009). Education in old age: An exploratory study. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 28(2), 241-276. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370902757125 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370902757125

- Mackowicz, J., & Wnek-Gozdek, J. (2016). “It’s never too late to learn”–How does the Polish U3A change the quality of life for seniors?. Educational Gerontology, 42(3), 186-197. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2015.1085789 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2015.1085789

- Maier, C., Laumer, S., & Eckhardt, A. (2011). Technology adoption by elderly people–an empirical analysis of adopters and non-adopters of social networking sites. In Theory-guided modeling and empiricism in information systems research, 85-110. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag HD. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7908-2781-1_5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7908-2781-1_5

- Martinez, D., Helsper, E. J., Casado, M. Á., Martinez, G., Larrañaga, N., Garmendia, M., Olveira, R., Salmela-Aro, K., Spurava, G., Hietajärvi, L., Maksniemi, E., Sormanen, N., Tiihonen, S., & Wilska, T.-A. (2023). Analysing Intervention Programmes: Barriers and Success Factors. A Systematic Review. KU Leuven: REMEDIS. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10357353

- Martínez-Alcalá, C. I., Rosales-Lagarde, A., Jiménez-Rodríguez, B., Galindo-Luna, D. A., Ramírez-Salavador, J. A., Aguilar-Lira, L., ... & Agis-Juarez, R. A. (2019, June). ICT Learning for Older Adults. In 2019 14th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), 1-6. IEEE. https://doi.org/10.23919/CISTI.2019.8760989 DOI: https://doi.org/10.23919/CISTI.2019.8760989

- Nef, T., Ganea, R. L., Müri, R. M., & Mosimann, U. P. (2013). Social networking sites and older users–a systematic review. International psychogeriatrics, 25(7), 1041-1053. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610213000355 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610213000355

- Novković Cvetković, B., Stošić, L., & Belousova, A. (2018). Media and information literacy-the basis for applying digital technologies in teaching from the discourse of educational needs of teachers. Croatian Journal of Education: Hrvatski časopis za odgoj i obrazovanje, 20(4), 1089-1114. https://doi.org/10.15516/cje.v20i4.3001 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15516/cje.v20i4.3001

- Qian, K., Zhang, Z., Yamamoto, Y., & Schuller, B. W. (2021). Artificial intelligence internet of things for the elderly: From assisted living to health-care monitoring. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 38(4), 78-88. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2021.3057298 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2021.3057298

- Quialheiro, A., Miranda, A., Garcia Jr, M., Carvalho, A. C. D., Costa, P., Correia-Neves, M., & Santos, N. C. (2023). Promoting digital proficiency and health literacy in middle-aged and older adults through mobile devices with the workshops for online technological inclusion (OITO) project: experimental study. JMIR Formative Research, 7, e41873. https://doi.org/10.2196/41873 DOI: https://doi.org/10.2196/41873

- Salo, M., Pirkkalainen, H., Chua, C. E. H., & Koskelainen, T. (2022). Formation and mitigation of technostress in the personal use of IT. Mis Quarterly, 46(2). https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2022/14950 DOI: https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2022/14950

- Sanecka, A. (2014). Social barriers to effective communication in old age. The Journal of Education, Culture, and Society, 5(2), 144-153. https://doi.org/10.15503/jecs20142.144.153 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15503/jecs20142.144.153

- Sayago, S., & Blat, J. (2007). A preliminary usability evaluation of strategies for seeking online information with elderly people. In Proceedings of the 2007 international cross-disciplinary conference on Web accessibility (W4A) (pp. 54-57). https://doi.org/10.1145/1243441.1243457 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/1243441.1243457

- Stojić, G. (2017). Internet Usage by the Elderly in Serbia. FACTA UNIVERSITATIS-Philosophy, Sociology, Psychology and History, 16(02), 103-115. https://doi.org/10.22190/FUPSPH1702103S DOI: https://doi.org/10.22190/FUPSPH1702103S

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications

- Szarota, Z. (2004). Gerontologia społeczna i oświatowa: zarys problematyki. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Akademii Pedagogicznej.

- Tattersall, C., Janssen, J., Van den Berg, B., & Koper, R. (2006). Modelling routes towards learning goals. Campus-Wide Information Systems, 23(5), 312-324. https://doi.org/10.1108/10650740610714071 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/10650740610714071

- Tomczyk, Ł. (2015). Edukacja osób starszych. Seniorzy w przestrzeni nowych mediów. Warszawa: Difin SA.

- Tomczyk, Ł. (2024). Digital competence among pre-service teachers: A global perspective on curriculum change as viewed by experts from 33 countries. Evaluation and Program Planning, 102449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2024.102449 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2024.102449

- Tomczyk, L., Mascia, M. L., Gierszewski, D., & Walker, C. (2023). Barriers to digital inclusion among older people: a intergenerational reflection on the need to develop digital competences for the group with the highest level of digital exclusion. Innoeduca. International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation, 9(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2023.v9i1.16433 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24310/innoeduca.2023.v9i1.16433

- Tristán-López, A., & Ylizaliturri-Salcedo, M. A. (2014). Evaluation of ICT competencies. Handbook of research on educational communications and technology, 323-336. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3185-5_26 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3185-5_26

- Vercruyssen, A., Schirmer, W., Geerts, N., & Mortelmans, D. (2023, September). How “basic” is basic digital literacy for older adults? Insights from digital skills instructors. In Frontiers in Education 8, 1231701. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1231701 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1231701

- Vidal, E. (2019, October). Digital literacy program: reducing the digital gap of the elderly: experiences and lessons learned. In 2019 International Conference on Inclusive Technologies and Education (CONTIE) (pp. 117-1173). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/CONTIE49246.2019.00030 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/CONTIE49246.2019.00030

- Vissenberg, J., Puusepp, M., Edisherashvili, N., Tomczyk, L., Opozda-Suder, S., Sepielak, D., Hietajärvi, L., Maksniemi, E., Pedaste, M., & d’Haenens, L. (2023). Report on the Results of a Systematic Review of the Individual and Social Differentiating Factors and Outcomes of Media Literacy and Digital Skills. KU Leuven: REMEDIS. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10356744

- Vuorikari, R., Kluzer, S. and Punie, Y. (2022). DigComp 2.2: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens - With new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes, EUR 31006 EN. , Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/115376

- Vuorikari, R., Punie, Y., Gomez, S. C., & Van Den Brande, G. (2016). DigComp 2.0: The digital competence framework for citizens. Update phase 1: The conceptual reference model (No. JRC101254). Joint Research Centre. https://doi.org/10.2791/607218

- Webster, F. (2014). Theories of the information society. London: Routledge. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315867854

- Zadražilová, I., & Vizváry, P. (2021, September). Digital literacy competencies and interests of elderly people. In European Conference on Information Literacy (pp. 137-146). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99885-1_12 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99885-1_12

- Zdjelar, R., & Žajdela Hrustek, N. (2021). Digital Divide and E-Inclusion as Challenges of the Information Society–Research Review. Journal of information and organizational sciences, 45(2), 601-638. https://doi.org/10.31341/jios.45.2.14 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31341/jios.45.2.14

- Ziemba, E. (2019). The contribution of ICT adoption to the sustainable information society. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 59(2), 116-126. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2017.1312635 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2017.1312635