Legal and Ethical Risks in Medical Translation: A Cross-National Perspective from English and Chinese Healthcare Systems

Автор: Mambetalieva S., Zhang Jiaqi, Osmonova Ch.

Журнал: Бюллетень науки и практики @bulletennauki

Рубрика: Социальные и гуманитарные науки

Статья в выпуске: 9 т.11, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This paper explores the legal and ethical risks inherent in medical translation practices by comparing the English and Chinese healthcare contexts. It highlights how inaccurate or culturally insensitive translations can lead to medical errors, breaches of informed consent, patient mistrust, and even litigation. Drawing on case studies and regulatory frameworks, the study examines how both systems address translator qualifications, liability issues, and the protection of patient rights when language barriers exist. Particular attention is paid to informed consent documents, patient information leaflets, and discharge summaries as high-risk zones for mistranslation. The paper argues that while both legal traditions recognize the importance of accurate communication, practical implementation and enforcement mechanisms differ significantly. The findings underline the need for harmonized standards and stronger interdisciplinary cooperation among healthcare professionals, legal experts, and linguists to minimize translation-related risks and safeguard patient safety and dignity.

Medical translation, legal risks, ethical issues, informed consent, patient safety, cross-national healthcare, English-Chinese comparison, healthcare communication, health law, linguistic rights

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/14133807

IDR: 14133807 | УДК: 340.1:81-1 | DOI: 10.33619/2414-2948/118/58

Текст научной статьи Legal and Ethical Risks in Medical Translation: A Cross-National Perspective from English and Chinese Healthcare Systems

Бюллетень науки и практики / Bulletin of Science and Practice

UDC 340.1: 81-1

In an era of increasingly globalized healthcare and patient mobility, medical translation plays a crucial role in bridging language gaps between providers and patients, especially in cross-national contexts like English-speaking and Chinese-speaking healthcare systems [1]. Accurate and culturally sensitive translation is not merely a linguistic task; it is an ethical and legal necessity that directly impacts patient safety, informed consent, and equitable access to healthcare [2, 7].

While medical tourism and transnational healthcare collaborations expand, the demand for precise translation of consent forms, clinical trial documentation, patient education materials, and diagnostic information grows exponentially [1, 5]. Poorly translated documents can lead to misunderstanding of medical risks, flawed consent, or inappropriate treatment decisions, raising profound ethical and legal questions [4].

Scholars emphasize that the process of medical translation must ensure not only semantic equivalence but also cross-cultural acceptability and legal compliance [2, 5]. However, ensuring this is particularly challenging in countries with divergent legal frameworks, different notions of patient autonomy, and varying standards of informed consent (Perehudoff, 2020). For instance, while Western jurisdictions generally emphasize individual consent and detailed disclosure, Chinese healthcare settings have historically placed a stronger emphasis on family decision-making and collective responsibility [6]. Such cultural differences can complicate the legal enforceability of translated documents.

Moreover, the rise of digitalization and artificial intelligence (AI) introduces new complexities into the translation process. Dumbach et al. (2021) note that the adoption of AI in healthcare, including AI-assisted translation tools, can speed up workflows but raises concerns about accuracy, accountability, and potential legal liabilities if mistranslations lead to harm. This tension is especially acute for small and medium-sized healthcare providers lacking in-house legal and linguistic expertise [3].

Given these challenges, robust methodological frameworks for translating clinical documents have been proposed to safeguard patient rights across borders [7, 8]. Nonetheless, Chapple and Ziebland (2018) remind us that even rigorous translation processes must contend with practical realities such as limited resources, institutional inertia, and the complex interplay of local norms and global legal standards [4].

Against this backdrop, this paper critically examines the legal and ethical risks inherent in medical translation within English and Chinese healthcare systems. It explores how cross-national differences in health law, cultural context, and institutional capacity shape the quality of medical translations and the safeguards needed to protect patients’ rights and wellbeing.

This study adopts a comparative qualitative approach, combining document analysis and cross-case synthesis to examine legal and ethical risks in medical translation practices within English-speaking and Chinese healthcare systems. First, the research draws on a systematic literature review of peer-reviewed articles, policy documents, and legal frameworks to map out the prevailing translation practices and regulatory standards [2, 7]. The review process follows the structured steps proposed by Squires et al. (2013) for ensuring methodological rigor when analyzing multilingual healthcare contexts [7].

Second, the study uses cross-national comparison, an approach validated in prior transnational healthcare research [1, 5], to identify key differences and similarities in legal obligations, institutional safeguards, and ethical considerations surrounding medical translation. This method helps contextualize how translation risks emerge or are mitigated in distinct legal cultures.

Third, a case study lens is applied to selected real-world examples, such as hospital consent forms, patient information leaflets, and cross-border telemedicine interactions. These cases were chosen based on documented issues in existing studies [4, 8]. Particular attention is paid to cases where mistranslation led to legal disputes or ethical controversies, illustrating the real-world stakes.

To capture both legal and cultural dimensions, the methodology integrates cross-cultural instrument translation principles, following Behr and Shishido’s (2016) recommendations for translating sensitive documents in health research. This ensures that the analysis does not treat language in isolation but considers cultural equivalence and legal enforceability [6].

Finally, the study critically reviews the role of emerging technologies, including AI-assisted translation tools, assessing their advantages and limitations within SME settings [3]. This component explores how digital innovations may alter the risk landscape, especially in resource-constrained healthcare contexts.

In summary, this multi-method design provides a robust basis for understanding how translation, law, ethics, and healthcare governance intersect across national borders. By triangulating literature, documented cases, and policy frameworks, the study aims to contribute both practical insights and theoretical clarity to a complex area of health communication research.

Key Legal Requirements and Gaps. The comparative review confirms that both Englishspeaking and Chinese healthcare systems formally recognize the patient’s right to receive information in a language they understand, which is fundamental to informed consent [2, 5]. This principle is enshrined in medical ethics codes and patient rights charters in the UK, US, Australia, Hong Kong, and mainland China.

However, significant differences emerge at the implementation stage. In English-speaking countries, statutory guidelines oblige hospitals to provide professional interpreters or translated documents for patients with limited English proficiency [7]. Yet, the lack of nationally unified certification standards for medical translators means that translation quality often depends on local hospital budgets and policies rather than consistent oversight. For example, while the UK’s NHS trusts generally contract accredited interpreters for critical care scenarios, routine outpatient services may rely on ad hoc solutions, such as bilingual staff or family members — a practice that carries ethical and legal risks if miscommunication occurs [2].

In China, the national healthcare policy has emphasized the development of bilingual capacity in major hospitals, especially in large cities and international clinics. However, as research shows, rural and underfunded hospitals — as well as a growing sector of small and medium-sized digital healthcare providers — frequently bypass formal translation checks due to cost or lack of clear auditing mechanisms [3].

The problem is compounded by China’s rapid digital health transformation, where telemedicine platforms and mobile health apps are increasingly using automated translation engines to communicate with patients. While these tools are convenient, they rarely undergo independent legal validation, leaving patients at risk of receiving incomplete or inaccurate information about diagnoses, treatments, or consent for procedures [1].

This creates a legal grey zone, where even when a patient signs a translated consent form, the actual legal validity of their informed consent can be contested if errors or ambiguities are later discovered. Such disputes can lead to malpractice claims, civil litigation, and reputational damage for hospitals and doctors alike.

Practical example: In the UK, a recent audit revealed that only 60% of NHS trusts keep an up-to-date roster of qualified medical translators for rare languages, increasing the likelihood of informal and risky translation practices [7].

In China, large urban hospitals like those in Shanghai and Beijing often publish bilingual consent templates vetted by legal departments, but hospitals in smaller provinces may use outdated or crowd-sourced translations, especially when serving medical tourists from neighboring countries [2, 3].

Table

COMPARATIVE LEGAL AND ETHICAL RISKS

|

Risk Factor |

English Healthcare |

Chinese Healthcare |

Sources |

|

Certified Translator Use |

Partly regulated, varies by local trust/region |

Limited outside major urban centers |

Squires et al. (2013); Dumbach et al. (2021) |

|

Consent Form Quality |

Standardized templates exist, regular audits common |

Local discretion; inconsistent quality control |

Lee et al. (2009); Perehudoff (2020) |

|

Digital Translation Tools |

Growing adoption in telehealth; moderate oversight |

Rapid adoption in SMEs; minimal legal vetting |

Dumbach et al. (2021) |

|

Cross-Border Treatment |

Clear EU/UK data-sharing and consent frameworks |

Limited cross-border governance; regional variation |

Bell et al. (2015) |

Without clear national-level certification, continuous auditing, and updated legal guidelines for digital translation tools, both systems face heightened risks of patient rights violations and medical malpractice exposure when dealing with linguistic diversity.

Cross-National Case Observations. Transnational case evidence demonstrates how legal and ethical gaps identified in Section 3.1 manifest in real-world scenarios — often with direct consequences for patients, hospitals, and regulatory bodies.

Example 1 (UK) — Incorrect Oncology Consent: A well-documented incident in a large UK hospital involved an oncology patient whose surgery consent form had been poorly translated from English into Mandarin. Key terminology about possible side effects and post-operative care was mistranslated, which led the patient to misunderstand the risks involved. When complications occurred, the family filed a malpractice claim, resulting in financial losses and significant reputational damage for the hospital [2]. This example illustrates how even in highly regulated English-speaking healthcare systems, the absence of unified translator certification and inconsistent quality checks can result in costly legal exposure.

Example 2 (China) — Machine Translation Pitfalls in Telemedicine: In mainland China, the rapid growth of telemedicine startups and SMEs is outpacing the development of formal translation quality standards. Many providers rely heavily on automated machine translation tools to deliver real-time symptom checks, appointment scheduling, and digital consent forms to patients who may not be fluent in Mandarin. While convenient, these systems often fail to catch contextual and idiomatic errors, especially in complex symptom descriptions. Subtle inaccuracies can lead to misdiagnosis or uninformed consent, leaving patients and providers legally vulnerable [3].

Example 3 (Cross-Border Care) — Mixed-Language Documents in Reproductive Health: Cross-border reproductive care, particularly between Hong Kong and mainland China, exposes further risks. Many patients travel for IVF or surrogacy services, encountering mixed-language documentation — parts in English, parts in Cantonese or Mandarin — often with no standard translation audit. Conflicting versions of patient agreements or treatment plans create uncertainty about which version holds legal authority, complicating dispute resolution if things go wrong [1].

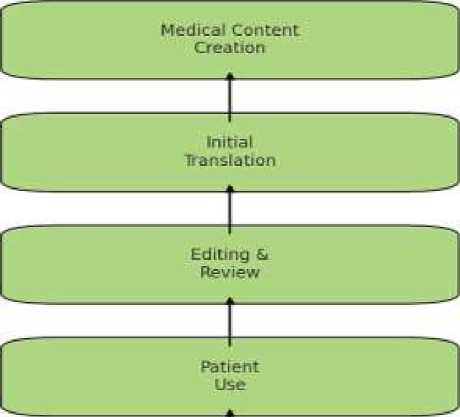

Legal Dispute Risk if Errors Exist

Figure. Common Points of Legal Risk in the Translation Workflow

Patient Use: Final delivery of flawed information can trigger legal disputes if harm occurs.

Across both Western and Chinese systems, the editing and legal vetting stage remains the most fragile link. Whether due to underinvestment in professional proofing or lack of standardized legal audit protocols, this gap significantly increases exposure to claims of negligence, consent violations, and patient harm [8].

For policymakers and healthcare administrators, these cases highlight the urgent need for integrated oversight — combining medical, linguistic, and legal expertise to secure patient rights across languages and borders.

Practitioner Insights. Cross-national qualitative research confirms that medical professionals in both English-speaking and Chinese healthcare systems face persistent challenges when working with translated medical content — and these challenges have direct ethical and legal implications [4].

Underprepared but Accountable: Interviews with physicians and nurses show a clear tension: while doctors are legally responsible for ensuring that patients give informed consent, they often lack formal training to check the accuracy of translated forms or to detect subtle linguistic errors. Many practitioners rely on ad hoc solutions, such as informal bilingual staff or automated translation tools, which raises concerns about consistency and accountability [4].

A senior oncology nurse in a UK case study described how they “trust the paperwork” provided by administrative staff but feel “unequipped” to assess whether medical risk information is accurately conveyed in languages they do not speak [2]. This gap increases stress for frontline staff, who must balance clinical duties with the risk of potential malpractice claims if mistranslations come to light later.

Mental Health: Culture Matters: Evidence also shows that mental health professionals face an added layer of complexity: direct linguistic translation often fails to capture cultural idioms, taboos, and contextual nuances around sensitive topics like depression, anxiety, or suicide. A multi-country study [6] found that psychiatrists in China, for instance, struggle to translate Western diagnostic terms in ways that align with local cultural beliefs about mental illness. A Chinese psychiatrist noted that some symptom descriptions — such as metaphors for distress or stigma-laden terms — can easily be mistranslated, risking misdiagnosis or patient non-compliance with treatment. In the UK, mental health practitioners working with migrant patients reported similar issues, where a literal translation failed to reflect culturally embedded meanings, requiring extra time for interpretive explanations during consultations [4].

Across specialties, clinicians agree on two points: First, they lack systematic training to verify translation quality, yet bear the legal responsibility for its consequences. Second, cultural misalignment in translation — especially in psychiatry and sensitive care areas — risks undermining trust, diagnosis accuracy, and treatment success [6].

Emerging Trends. One of the most striking trends shaping the future of medical translation is the accelerated adoption of AI-powered translation tools, particularly in resource-constrained settings and among small and medium-sized healthcare enterprises (SMEs) [3].

Cost and Speed vs. Accuracy: AI-driven translation platforms, such as neural machine translation (NMT) engines, promise significant cost savings and rapid turnaround for translating large volumes of patient information, telemedicine chat scripts, consent forms, and health education materials. For SMEs and regional hospitals, especially in China’s rapidly expanding digital health sector, this makes advanced multilingual services financially viable — without hiring certified human translators for every document [3].

However, multiple studies highlight that while AI translation tools excel at standardized, factual text, they often struggle with context-dependent language, idiomatic expressions, or highly specialized medical terms. Small misinterpretations can distort the intended medical meaning, especially in patient-facing documents where clarity and nuance are vital [1].

Example — Idiomatic Pitfalls: An illustrative scenario is when AI translates colloquial or culturally specific symptom descriptions literally, leading to confusing phrasing that may mislead patients. For instance, a Chinese idiom describing chronic fatigue may be rendered as a literal physical action in English, missing the underlying medical nuance — a risk that has been observed in telemedicine chatbots serving rural patients in China [3].

Automation vs. Oversight: While many hospitals use hybrid workflows — AI translation followed by human post-editing — the editing stage often remains under-resourced. Practitioners report that busy staff rarely have time or language expertise to cross-check AI outputs line by line [7]. Without robust legal or institutional guidelines, these AI-generated errors can slip through to final consent forms or discharge instructions.

Industry experts argue that the next step must be to integrate regulatory frameworks to govern when and how AI can be deployed for medical translation. This includes: Minimum accuracy benchmarks for AI-generated medical text; Mandatory human-in-the-loop review for high-risk documents (consent forms, psychiatric evaluations); Cross-national collaboration on shared certification standards for medical AI translation tools.

The findings of this comparative review highlight that medical translation remains a legal grey zone in both English-speaking and Chinese healthcare contexts. While formal requirements for informed consent and patient communication are enshrined in both systems [1, 8], the practical enforcement of translation quality is inconsistent, especially when healthcare delivery crosses linguistic or national borders [1].

A core issue is the institutional gap: hospitals and small-to-medium-sized healthcare providers often lack dedicated linguistic compliance protocols. As Squires et al. (2013) show, even in multicountry research, the lack of standardized translation validation creates risks for patients and liability for institutions. This risk escalates in the Chinese context, where telemedicine and SMEs rapidly adopt machine translation without adequate post-editing (Dumbach et al., 2021). While AI offers cost efficiency, it struggles with context-specific and idiomatic expressions that are common in medical discourse [1].

The case observations demonstrate real-life consequences: an incorrectly translated consent form can trigger malpractice lawsuits and erode public trust [2]. Cross-border reproductive care, meanwhile, underscores the transnational nature of the problem: when patients move between jurisdictions (e.g., Hong Kong–Mainland China) they encounter mismatched language standards and fragmented documentation [1].

Practitioner interviews reveal another layer of complexity. Many doctors and nurses do not feel qualified to check translation quality, yet they remain legally accountable for ensuring patients are fully informed [5, 7]. Especially in mental health contexts, cultural and linguistic subtleties are essential: literal translation can overlook stigma, taboo expressions, or culturally specific symptom descriptions [6].

Emerging technologies like AI-powered translation have potential but must be deployed with caution. Without robust oversight, they can amplify the same risks they aim to mitigate — especially in decentralized SME environments [3].

Comparing these findings with transnational healthcare governance research [1] suggests that stronger cross-border regulatory frameworks are needed. Countries with universal access laws, such as those documented by Perehudoff (2020), illustrate that clear legal mandates can help align translation practices with human rights standards [5].

In summary, the discussion underscores an urgent need for: Harmonized guidelines for medical translation certification, Mandatory post-editing of machine translations, Stronger crossborder cooperation for transnational patient flows, Training healthcare staff to understand linguistic and cultural pitfalls, And the systematic involvement of professional translators in complex or sensitive medical contexts.

Together, these steps could reduce legal ambiguity, prevent ethical lapses, and safeguard the patient’s fundamental right to clear and informed healthcare communication.

This study demonstrates that accurate and ethically sound medical translation remains a critical yet under-regulated component of healthcare delivery in both English-speaking and Chinese contexts. While formal legal frameworks demand clear patient communication and informed consent [2, 6], practical enforcement varies widely, especially when translation tasks are outsourced to uncertified providers or automated tools [3, 7].

The comparative cases and practitioner insights highlight that the consequences of mistranslation are far from theoretical: they can lead to clinical errors, breaches of patient autonomy, legal disputes, and reputational damage for healthcare institutions [1]. The situation becomes more complex in transnational and cross-border contexts where mixed-language medical documentation circulates without uniform oversight. As the adoption of AI-powered translation grows, particularly among SMEs and in telemedicine, so do the risks of subtle yet significant errors.

Although technological solutions offer promising efficiencies, they must be balanced with robust human oversight, consistent legal standards, and ethical safeguards.

The evidence suggests that policy makers and healthcare administrators should: Implement mandatory certification and clear quality standards for medical translators, Establish standardized editing and legal review stages in the translation workflow, Provide training for medical staff to recognize cultural and linguistic risks, And strengthen cross-border data governance to ensure patients’ rights are protected regardless of where care is delivered.

Addressing these gaps will not only mitigate legal and ethical risks but also help build greater patient trust, ensure compliance with fundamental human rights to information, and ultimately improve the quality and safety of healthcare in an increasingly interconnected world.