Prospective Teachers' Epistemological Beliefs and their Perceptions of Learning through Tools within their Digital Culture

Автор: Zaid Abdelkarim, Ou-sekou Youssef, Fatiha Kaddari

Журнал: International Journal of Education and Management Engineering @ijeme

Статья в выпуске: 2 vol.15, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The objective of this article is to characterize the personal epistemological beliefs of prospective primary school teachers regarding their learning experiences through specific digital tools related to their digital culture. The research is conducted in the form of a survey among a sample of prospective primary school teachers in Morocco. The results of this study indicate that the beliefs of prospective teachers vary depending on the digital tool used. Prospective teachers state that the content posted on social networks and personal blogs of trainers is understandable. They are willing to question content published on social networks, while a great number of subjects are inclined to question content published on personal blogs and institutional portals. They fully accept ideas and content published on networks and personal blogs by authors whom they consider more experienced than themselves. They also state that they rely on experts rather than trusting a consensus of respondents regarding a given conten.

Epistemological Beliefs, Personal Epistemology, Digital Culture, Prospective Teachers, Teachers’ Training

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/15019854

IDR: 15019854 | DOI: 10.5815/ijeme.2025.02.03

Текст научной статьи Prospective Teachers' Epistemological Beliefs and their Perceptions of Learning through Tools within their Digital Culture

The discourse of Moroccan educational policy is focussed on teacher training and considers this an indicator of each reform. Faced with this institutional interest, the scant existing research on education and training in Morocco appears mitigated. Indeed, analysing the reform of teacher training in Morocco, [1] enumerates a number of shortcomings at various levels: quality, organization, pedagogy, management and participants (Conflict between central decision making, and that of the ministry, regions and regional academies). However, [2], concentrating on the digital skills of future teachers in their initial training, affirm that searching for information on the Internet is common among the latter, whose declared practices reveal a certain facility with respect to their technical, social and informational use of ICT. In particular, in characterizing the digital culture of future Moroccan teachers in the course of primary education training, [3] shows that the digital culture of prospective teachers is rooted in their personal usage of different tools and resources. Future teachers’ digital practices are characterized by a frequent usage of social media and a low tendency to use institutional platforms. These observations lead us to investigate prospective teachers’ epistemological beliefs regarding knowledge constructed from the digital tools employed: social media, trainers’ personal blogs and institutional portals.

Epistemological beliefs have been the subject of considerable research ([4,5,6,7,8,9]). They are considered to be a construction with a significant impact on teachers’ behaviour and practices, as well as on prospective teachers’ conception of training programs [10]. Much research examines the relations between epistemological beliefs and approaches to teaching and learning ([11,12,13,14]). [15] analyse epistemological beliefs and their relation to the knowledge developed by students engaged in a training program reorganized for Quebec high school teachers.

The importance of focussing research on teachers’ epistemological beliefs is underscored by a number of researchers. Indeed, [16] affirms that, even if initial teacher training undertakes the transmission of tools of the trade, the crucial task of mobilizing these tools in new contexts and situations, never seen in the course of their training, is left to teachers themselves. Beliefs give meaning to teachers’ experiences in contradictory situations in the classroom: taking into consideration each student’s needs and interests, all while maintaining a common foundation of knowledge [17]. For [17] beliefs contribute to the professionalization of teachers, as does their understanding of their needs and their profession; they also support the construction of teachers’ social and personal identities. It is very important in the future to invest in research on students’ and teachers’ beliefs. Research on their epistemological and pedagogical beliefs will offer possibilities for intervention in the existing models of teacher training, to enhance the quality of teacher training, to improve the methodology of working with teachers and to help them improve their actual work [18].

More particularly, [19] affirm that personal epistemological beliefs impact an individual’s cognitive functioning in a remarkable fashion. Notably, they influence teachers’ ways of conceiving of teaching. Therefore, it seems important, both for researchers and for trainers of prospective teachers, to understand the prospective teachers’ epistemological beliefs [19].

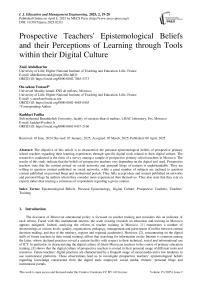

Personal epistemology is defined by [9] as a field of research which is interested in beliefs and also theories developed with respect to individuals’ knowledge and its acquisition. According to [20], personal epistemology has two major dimensions: the nature of knowledge and the nature or process of knowing. Below (Fig. 1) is the structuring of four subdimensions of personal epistemology according to [20]:

Fig. 1. Hofer’s and Pintrich’s Model of Personal Epistemology (1997)

The four subdimensions examine:

• Certainty of knowledge: whether knowledge is fixed or evolving.

• Simplicity of knowledge: whether knowledge is compartmentalized or integrated.

• Source of knowledge : whether knowledge comes from external authority or personal construction.

• Justification for knowing (how individuals evaluate knowledge claims.

2. Methodology

2.1 Participants

Each dimension was adapted to specifically address digital contexts in our instrument

According to [9], the majority of research on personal epistemology has dimensions relative to the following three questions: What is knowledge? How is it acquired? How is knowledge constructed and evaluated?

Most of this research is interested principally in questions related to the links between prospective teachers’ epistemological beliefs and their cognitive processes during their learning, without specifying the tools utilized during this learning. Our study addresses a significant gap in understanding how epistemological beliefs specifically operate within digital environments. While extensive research exists on epistemological beliefs in traditional learning contexts [9,10], few studies have examined how these beliefs function across different digital tools that prospective teachers actually use. Most previous work treats digital tools as a monolithic category rather than distinguishing between social networks, blogs, and institutional portals as we have done. This distinction is crucial given the varied nature of authority, community validation, and information presentation across these platforms. Our contribution consists of investigating future teachers’ personal epistemology (that is, describing epistemological beliefs) with respect to what they learn via the significant digital tools of their digital culture (social media, personal blogs and institutional portals) based on [9] and the results of the study of [3]. Thus, two research questions are essential: What knowledge is accessible through the significant digital tools in the digital culture of prospective teachers? How is this constructed and evaluated through these digital tools?

Organized as a case study, the investigation was conducted among prospective teachers of the Centre Régional d'Education et de Formation - CRMEF – Meknès (Meknès is a medium-sized city in central Morocco). The authorization to conduct the study was granted by the CRMEF. The process was completely anonymous, and no personal identifiers were used in the study.

The study participants were 56 students training to be primary teachers at the CMREF training centre. These students have degrees in various disciplines, including sciences (mathematics, physics-chemistry, biology…), social sciences and humanities (French literature, English studies, Arabic literature, history and civilization…) and economics and other social sciences. The questionnaire was administered in paper format at the CMREF to two different groups. The objectives of the research were explained to the future teachers, who were accompanied to respond to the questionnaire (The questionnaire being in French for students whose language of study was basically Arabic). The 56 future teachers of the CMREF Meknès centre included 41 women (73.2%) and 15 men (26.8%). The dominant age group was that between 26 and 30 years old (42.9%), while a minority were between 31 and 35 (12.5%). Bachelor’s degrees predominated (83.9%), while 8 future teachers had obtained their masters (M) (14.3%). A single future teacher had a doctorate. The field of science and technology (ST) was dominant (41.1%), with social sciences representing 30.4% and economic and legal studies constituting 28.6%.

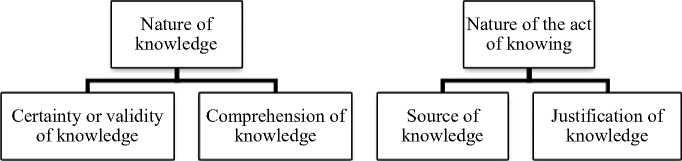

The figure Fig. 2, summarizes the future teachers’ previous experience, expressed in number of months, given its minimal nature among future teachers. Most had no previous teaching experience, although a minority claimed to have considerable experience.

Fig. 2. Previous Teaching Experience (in number of months)

2.2 Data collection instrument

3. Results

3.1 Profiles of the personal epistemology of future teachers3.2 The nature of knowledge

Based on the model of [20], a questionnaire was developed to inquire about future teachers’ epistemological beliefs with regard to their learning developed through digital tools which characterize their digital culture. Questions are associated with each subdimension of the model of [20]. Thus, six items are chosen for the subdimension certainty of knowledge, three items for the comprehension of knowledge, six items for the subdimension the source of knowledge, and six items for the subdimension the justification of knowledge. The responses were collected following a Likert five level scale (0: Completely disagree; 1: Disagree; 2: Neutral; 3: Agree; 4: Completely agree). The questionnaire also includes a section requesting demographic data such as sex, age, the field of study, the academic level, and whether or not the future teacher has had training in educational technologies.

To verify the reliability of the data collection instrument, we proceeded with two tests: on one hand, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to test the consistency of all the items of our questionnaire (20 items in total); on the other hand, indices of item-total correlation were used to verify whether an item was well chosen for each subdimension and whether it reveals a significant correlation with the total score of each subdimension. Cronbach’s coefficient (Table 1) was superior to 0.6 for the 20 items on the four subdimensions of future teachers’ personal epistemology, which demonstrates its validity according to [21].

Table 1. Reliability Tests for Questions on Epistemological Beliefs

|

Subdimensions |

Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient |

|

Certainty of knowledge |

.68 |

|

Simplicity of learning |

.61 |

|

Source of knowledge |

.63 |

|

Justification of knowledge |

.67 |

A paper version of the questionnaire was distributed, and the future teachers responded in person, considering all the questions, and eliminating any possibility of ambiguity on the proposed items. To minimize bias, researchers provided standardized Arabic explanations for Francophone participants and addressed ambiguities in real-time. Anonymity was ensured. Subsequently, all the questionnaires were collected, and the data were entered into SPSS version 23.0.

To describe the beliefs of future teachers regarding each subdimension, we calculated the averages of each item for all the subjects for each subdimension of the model of [20]. Each average calculated falls within a significant interval according to the five-point Likert scale. The tables ( Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5) present the relevant data obtained.

As for the certainty of knowledge and learning, Table 2 represents the averages of items which comprise the first subdimension: certainty of knowledge, and its significance according to the five-point Likert scale.

Table 2. The Averages of Items from the Subdimension Certainty of knowledge for Primary Education (This table presents the items constituting the first subdimension “Certainty of knowledge” from the model of de Hofer and Pintrech (1997) and their calculated averages.).

|

Items |

Average item |

Likert Interval |

Significance |

|

I sometimes question the ideas presented on social media* |

3.98 |

3.40-4.19 |

Agree |

|

I sometimes question the ideas presented on trainers’ personal blogs. |

3.34 |

2.60-3.69 |

Neutral |

|

I sometimes question the ideas presented on institutional portals |

3.21 |

2.60-3.69 |

Neutral |

|

The content presented on social media does not contradict scientific principles |

2.45 |

1.80-2.59 |

Disagree |

|

The content presented on personal blogs does not contradict scientific principles |

2.73 |

2.60-3.69 |

Neutral |

Note . *: For this item, for example, we calculate its average for all the subjects; then, based on the Likert intervals, we can deduce the significance of the average. For this item, the epistemological beliefs are in accordance with the questioning of content published on social media.

As for the understanding of knowledge and learning, Table 3 represents the averages of items which comprise the first subdimension: comprehension of learning and its significance according to the five-part Likert scale.

Table 3. The Averages of Items of the Simplicity of learning Subdimension for Primary Education (This table presents the items constituting the second subdimension “Simplicity of Learning” from the model of Hofer and Pintrech (1997) and their calculated averages).

|

Items |

Item Average |

Likert Interval |

Significance |

|

The content presented on social media is difficult to understand. |

2.21 |

1.80-2.59 |

Disagree |

|

The content that the trainers publish on their personal blogs is difficult to understand. |

2.54 |

1.80-2.59 |

Disagree |

|

The content that students and future teachers publish on their personal blogs is difficult to understand. |

2.36 |

1.80-2.59 |

Disagree |

-

3.3 The Process Linked to the Act of Knowing

3.4 The knowledge accessible through digital tools drawn upon by future teachers.

Here this is a matter of characterizing the manner in which the future teachers come to know something through digital tools. As for the source of knowledge and learning, Table 4 presents the averages of items comprising the first subdimension: the source of learning, and its significance according to Likert’s five-point scale.

Table 4. The Averages of Items of the Subdimension Source of Learning for Primary Education (This table presents the items constituting the third subdimension “Source du savoir” from the model of Hofer and Pintrech (1997) and their calculated averages.)

|

Items |

Item Average |

Likert Interval |

Significance |

|

Sometimes I accept the content on social media even if I do not understand it |

1.89 |

1.80-2.59 |

Disagree |

|

Sometimes I accept the responses given on personal blogs (even if I do not understand them). |

1.88 |

1.80-2.59 |

Disagree |

|

The content of an article found on social media is true. |

2.32 |

1.80-2.59 |

Disagree |

|

The content of an article found on a personal blog of a trainer is true. |

2.66 |

2.60-3.69 |

Neutral |

|

I consider the content provided on a social network or a personal blog to be true even if it is in conflict with my point of view. |

1.96 |

1.80-2.59 |

Disagree |

|

I’m more certain of my learning when it is consistent with what is published on social media, on personal blogs and on institutional portals. |

3.29 |

2.60-3.69 |

Neutral |

For the justification of knowledge and learning, Table 5 displays the averages of items constituting the first subdimension: justification of learning, and their significance according to the according to the five-point Likert scale.

Table 5. The Averages of Items of the Subdimension Justification of Learning for Elementary School (This table presents items constituting the fourth subdimension “Justification of Learning” from the model of Hofer and Pintrech (1997) and their calculated averages).

|

Items |

Item Average |

Likert Interval |

Significance |

|

What I consider learning acquired from social media and personal blogs is based on fundamental principles in each domain. |

3.25 |

2.60-3.69 |

Neutral |

|

What I consider true on social media is based on a consensus of authors, or on the opinions of experts. |

2.75 |

2.60-3.69 |

Neutral |

|

What I consider true on personal blogs is based on a consensus of authors, or on the opinions of experts. |

2.79 |

2.60-3.69 |

Neutral |

|

On social media, there are means by which one can determine whether someone is right or not. |

2.63 |

2.60-3.69 |

Neutral |

|

On personal blogs, there are means by which one can determine whether someone is right or not. |

2.66 |

2.60-3.69 |

Neutral |

|

You accept the ideas of those who are more experienced than you to evaluate what you learn from social media and personal blogs or you always refer to experts. |

3.61 |

3.40-4.19 |

Agree |

It is noteworthy that the questionnaire was used in person in order to remove any sort of ambiguity for each item. Thus, we explained to the future teachers that the response to a question, for example, in the form: “What I consider true on social media is based on a consensus of authors, or on the opinions of experts” on a five point Likert scale, comes back to choosing either the consensus or the opinion of an expert; and, thus, saying, for example “Disagree” for the item does not signify “Disagreeing” with the consensus and automatically validating the expert.

The certainty of knowledge and learning: In this subdimension, we are interested in verifying the extent to which future teachers consider knowledge and learning from social media and their trainers’ personal blogs, fixed or modifiable using authentic criteria (for example, fundamental scientific principles). Analysis of the averages in Table 2 shows that the future teachers reveal homogeneous beliefs with respect to what they learn from social media. The other beliefs with respect to learning and knowledge from trainers’ personal blogs and institutional portals are heterogeneous.

For social media, the significance of the average obtained according to the five-point Likert scale is “agree” (Table 2) . An analysis of percentages shows that 42.86% of future teachers are in favour of questioning ideas and content published on Facebook during their studies. It is noteworthy that, regarding the content published on the trainers’ blogs, the future teachers are neutral. An analysis of percentages reveals that 35.5% of future teachers are neutral in that respect, while 44.64% are in favour of questioning the content and ideas published on their trainers’ personal blogs.

As for the ideas and content published on institutional portals, the results show that the future teachers are neutral in their beliefs (Table 2) . An analysis of percentages reveals that 44.64% of future teachers are in favour of questioning ideas and content published on institutional portals. A considerable portion of future teachers claim to be neutral in their epistemological beliefs (37.5%).

The last two items on the certainty of knowledge subdimension question future teachers as to whether or not content published on social media or on their trainers’ personal blogs contradicts the scientific principles of each field or speciality. By scientific principles, we mean all the definitions, axioms, and common rules of each field (technical sciences or social sciences). We postulate that institutional portals cannot publish content which contradicts scientific principles.

The average for this item (Table 2) shows beliefs confirming that the content published on social media sometimes contradicts scientific principles. In other words, the majority of future teachers (66.07%) affirm that the publications on social media contradict scientific principles at times. The same result is noted with respect to the content and ideas published on trainers’ personal blogs. 46.43% of future teachers affirm that the content and ideas published on trainers’ personal blogs may contradict scientific principles.

The comprehension of knowledge: Through the items constituting this subdimension, we attempt to determine whether or not the learning from social media, trainers’ personal blogs and institutional portals poses difficulties for future teachers in terms of comprehension. The averages calculated for the items of this subdimension show that the future teachers reveal homogeneous beliefs with respect to the simplicity of the knowledge and learning stemming from social media, trainers’ personal blogs and institutional portals (Table 3) .

The future teachers reveal homogeneous beliefs developed about the simplicity of content and ideas published on social media. The majority of future teachers (64.28%) affirm that they understand the content published on social media.

The comprehension of published content and ideas is not just restricted to social media. Indeed, the results confirm the same finding for trainers’ personal blogs. A considerable proportion of future teachers (44.64%) affirm that they understand the content and the ideas published on their trainers’ personal blogs. We note that a substantial number (46.43%) of these future teachers reveal neutral beliefs with regard to the complexity of content and ideas on their trainers’ personal blogs. The same observations extend to the content and ideas on institutional portals (Table 3). Indeed, 50% of future teachers declare that they understand the content and ideas on institutional portals. A considerable proportion of future teachers (46.43%) claim to be neutral with respect to the complexity of content and ideas on institutional portals.

-

3.5 How is knowledge constructed through these tools?

-

3.6 How is knowledge evaluated via these tools?

Here, the focus is on identifying how future teachers come to know something through the digital tools employed. The items in Table 4, aim to determine the source of future teachers’ learning through social media and personal blogs. The results will be presented in response to four questions with which the corresponding items will be associated.

Do future teachers “build” their learning autonomously? The item corresponding to this question is: I am more sure of my learning when it is consistent with what is published on social media, personal blogs and on institutional portals. The average of the item on Table 4, shows that future teachers’ beliefs are heterogeneous, which is confirmed by an analysis of percentages. The dominant beliefs expressed are completely consistent with the existence of learning developed autonomously by the future teachers.

Are social media and trainers’ personal blogs external authorities which transmit learning to them? Here, we consider that institutional portals are purported to constitute an official authority for the transmission of learning. The objective of this question is to verify whether the learning offered by social media and trainers’ personal blogs is external and transmitted with a degree of certainty to future teachers. We associate two items with this question: The content of an article found on social media is true and the content of an article found on trainers’ personal blogs is true. The average for the two items Table 4, reveals homogeneous beliefs (expressing a majority position) regarding the networks and heterogeneous beliefs (not displaying a majority position) regarding trainers’ personal blogs. For social media, the dominant beliefs of future teachers (66.07%) show that they do not consider social media as an external authority for the transmission of learning. For trainers’ personal blogs, an analysis of frequencies reveals heterogeneous beliefs. 51.78% of future teachers do not consider the personal blogs of their trainers an external authority for the transmission of learning.

Do future teachers manage to construct learning through interactions with others on social media and via the personal blogs of their trainers? The digital tools of social media (WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram…) and trainers’ personal blogs all offer functionalities of synchronous or asynchronous interactions. The focus of this question is to determine whether the future teachers construct learning through interactions with others on social media and their trainers’ personal blogs. The item associated with this question is: I consider the content provided on social media or on personal blogs as true, even if it is in conflict with my own perspective. The future teachers have homogeneous beliefs. The analysis of frequencies shows that the majority of future teachers (75%) reject the role of interactions with others on social media and on personal blogs in the construction of their learning.

Are future teachers capable of constructing the meaning of learning stemming from social media and personal blogs? This question aims to determine whether future teachers develop meaning from learning stemming from social media and personal blogs. This question is related to two items: Sometimes I accept the content on social media even if I do not understand it, and sometimes I accept the answers provided on personal blogs (even if I do not understand them. The averages in Table 4, show that future teachers’ beliefs are homogeneous. Analysis of the percentages reveals that the majority of future teachers (80.36%) do not accept learning stemming from social media without understanding the meaning. The same finding is also confirmed with respect to trainers’ personal blogs. The average of Table 4, displays homogeneous beliefs. An analysis of percentages reveals that the majority of future teachers (80.36%) disagree wholeheartedly with accepting learning from their trainers’ personal blogs if they fail to understand it.

The objective of this section is to identify how future teachers justify and evaluate learning from social media and their trainers’ personal blogs. We hypothesize that learning from institutional portals is purported to constitute the norm and does not require any particular evaluation. The items which comprise this subdimension are listed in Table 5 . In this subdimension we have asked the future teachers about the role of their personal experience, as well as that of the experience of others, in their beliefs. We have also inquired about the influence of the consensus of others and of experts on these future teachers’ epistemological beliefs. Consequently, two questions were formulated: To what do future teachers refer to evaluate the learning and knowledge stemming from social media and their trainers’ personal blogs? What is the role of the expert in future teachers’ beliefs faced with experience, and with the consensus of respondents on something published on social media and on their trainers’ personal blogs? Again, to answer these questions, we associate with each question the corresponding items from Table 5.

To what do future teachers refer to evaluate the learning from social media and their trainers’ personal blogs? To respond to this question, we have examined the role of each field’s fundamental scientific principles in the process of evaluating learning and knowledge from social media and their trainers’ personal blogs. The possible existence of other means, besides the fundamental scientific principles of each field, allowing for intervention in this process was also examined. Three items are associated with this: What I consider learning stemming from social media and personal blogs is based on fundamental principles of each field; On social media, there are means of determining whether an individual is right or not; and on trainers’ personal blogs, there are means by which one can determine whether an individual is right or not. The averages calculated for the three items show that future teachers’ beliefs are heterogeneous (Table 5) . An analysis of percentages for each item allows us to describe future teachers’ beliefs.

With regard to the fundamental scientific principles of each domain, the future teachers reveal heterogeneous beliefs. Indeed, the majority of future teachers (53.57%) affirm that they always verify that the learning and knowledge stemming from social media and personal blogs respect the fundamental scientific principles of each field.

We also questioned the future teachers as to whether they subject the learning and knowledge stemming from social media and personal blogs to other criteria than fundamental scientific principles for purposes of evaluation. For social media, future teachers’ beliefs are heterogeneous. The dominant beliefs among future teachers (51.78%) tend to deny the existence of means to evaluate the learning and knowledge stemming from social media. The same finding was confirmed for trainers’ personal blogs. Future teachers claim heterogeneous beliefs. Their dominant beliefs (48.21%) tend to also deny the existence of means to evaluate the learning and knowledge stemming from their trainers’ personal blogs.

What is the role of the expert in the beliefs of future teachers faced with the respondents’ experience and consensus on learning published on social media and on their trainers’ personal blogs? This question seeks to determine whether future teachers rely on consensus, an expert or experience to evaluate the learning from social media and their trainers’ personal blogs. In accepting that experts in each field are authorized to evaluate learning in their speciality, we examine the tendency of future teachers’ beliefs when they must choose between the opinion of the expert and the consensus of others, and between the expert and another individual who is more experienced in a particular field.

The averages calculated for the items concerning the role of the expert given a consensus of respondents regarding learning or knowledge published on social media and on trainers’ personal blogs displays witness to heterogeneous beliefs (Table 5) . An analysis of percentages shows that 55.36% of future teachers turn to the expert, versus 39.29% relying on the consensus to evaluate the learning from social media.

The same observation for social media is confirmed for the trainers’ personal blogs. Analysis of the percentages shows that 50% of future teachers turn to experts to evaluate the learning from their trainers’ personal blogs, compared to 41.07% who believe in the consensus of respondents on these personal blogs. The average of the item on the role of the expert compared to experience shows homogeneous beliefs for the future teachers (Table 5) . Analysis of percentages reveals that 73.21% of future teachers prefer to refer to a more experienced individual to evaluate the learning from social media and personal blogs rather than taking an expert’s opinion into account.

4. Discussion

In this article, we show that the epistemological beliefs of future teachers vary depending on the digital tools utilized. This heterogeneity of epistemological beliefs with respect to digital tools is confirmed by the results of [22], showing that researchers noticed a positive but different attitude among future teachers towards the usage of digital tools in teaching English. This is also consistent with the results of [23] and [24] who demonstrated a potential relationship between future teachers’ epistemological beliefs and the integration of technologies in their future teaching. Given that each digital tool is characterized by its own digital environment and its own services/resources offered to the user of this environment, it seems that future teachers’ varied choices of digital tools lead to different learning processes for each digital tool.

This paper also reveals future teachers’ homogeneous epistemological beliefs regarding the comprehension of content published on social media and on personal blogs. Future teachers declare that the content published on social media and on personal blogs is simple and accessible. These results are in line with those of [22] and [25], whose results show that future teachers find the content published on social media simple and easy to integrate into their future pedagogy.

For future teachers, the learning acquired via social media, their trainers’ personal blogs and institutional portals is not “absolute” and is liable to be called into question. The results show that most of them are in favour of questioning content published on social media, on personal blogs and on institutional portals. This uncertainty about the publications on social media is corroborated by [26] who conclude that 56% of the publications on social media by those in initial training to teach elementary school were inappropriate. Ultimately, the results confirm those of [27] who led a study on the contribution of personal blogs and common blogs to the professional development of students in teacher training. The author concluded that the majority of future teachers declare positive tendencies with respect to the content published on personal blogs. Future teachers draw upon fundamental principles of science to test the nature of their learning. They affirm that the content published on networks and their trainers’ personal blogs sometimes contradicts fundamental scientific principles.

Teachers’ skepticism toward social media content (e.g., 66.07% noting contradictions with scientific principles) suggests potential for fostering critical thinking. Conversely, reliance on experts may mirror traditional pedagogies, highlighting a need for balanced digital literacy training.

Two other results are worthy of mention, with respect to the nature of future teachers’ search for knowledge via digital tools: social media and personal blogs. The first result concerns the construction of learning: whether it is autonomous, produced as a result of incitement by an external authority (social media and personal blogs) or via interactions with other users of social media and personal blogs. The second result is related to future teachers’ construction of the meaning of what they have learned. The autonomous construction of learning by future teachers may be interpreted as the product of their experience in the usage of technologies, which develops their self-determination and the exploration of their identity [28]. In this sense, the future teachers declare that they are constructing autonomous learning provided that it is consistent with what is published on social media and on blogs. This finding also demonstrates that social media and blogs can be seen as authorities influencing the construction of learning by future teachers. Nevertheless, this affirmation is tempered by the fact that future teachers are not sure whether the content published on social media and on personal blogs is true. They declare that they do not trust interactions with peers to develop their learning or to verify the truth. Moreover, other research stresses the limited role of interactions in the construction of learning in that they remain influenced by epistemological beliefs [29] or by the nature of the published content, favouring independence instead [30]. Future teachers claim to refuse all sorts of learning published on social media and on their trainers’ personal blogs if they do not manage to understand it. Social media’s informal, peer-driven nature invites questioning, while institutional portals’ formality reduces scrutiny. Blogs, as semi-formal hybrids, occupy a middle ground, explaining tool-specific belief variations

To validate the knowledge acquired on social media and on personal blogs, the majority of future teachers claim to refer to fundamental principles of each field to determine whether the publications respect them or not. This result shows that future teachers construct their knowledge in basing it on scientific evidence, and this corroborates the results of [31] who show that, of the 29 prospective Australian teachers in their study, 62% believe that knowledge is constructed individually based on scientific evidence.

Our results show that the future teachers accept the ideas, and the content published on the networks and on personal blogs by those who are more experienced, rather than referring to an expert on these tools. This important impact of others’ experience on their own beliefs is not confirmed by [19], who show that future teachers believe in the evaluation of experts during the acquisition of new knowledge. The impact of the expert on future teachers’ beliefs changes when they are faced with a consensus on a certain subject. They claim to turn to experts rather than having faith in the consensus of authors on this subject.

Based on our findings, we recommend that teacher education programs explicitly address epistemological reasoning across digital platforms; incorporate activities that require critical evaluation of content from various digital sources; leverage prospective teachers' existing comfort with social media while building bridges to institutional platforms; and develop assessment methods that capture how epistemological beliefs manifest in digital teaching practices. Teacher educators should also model sophisticated epistemological reasoning when using digital tools in their own teaching.

5. Conclusion

This article seeks to characterize the epistemological beliefs of future teachers relative to knowledge developed through digital tools. The results show that future teachers’ epistemological beliefs vary depending on the digital tool employed, which leads to different learning processes for each digital tool. Specifically, in relation to the four subdimensions of personal epistemology, four observations may be formulated. First, the future teachers question the content and ideas published on social media, their trainers’ personal blogs and on institutional portals. They affirm that the content published on social media and on their trainers’ personal blogs is not always consistent with the scientific principles of each domain. Secondly, future teachers affirm that the content published on social media and on personal blogs is simple and accessible (in terms of comprehension). Thirdly, future teachers contribute effectively to the development of their learning from social media and their trainers’ personal blogs. They refuse to consider social media and their trainers’ personal blogs as authorities in terms of learning; they claim that discussions with others through social media and trainers’ personal blogs do not contribute to the development of their learning. The future teachers add that they do not accept incomprehensible content from these social media and trainers’ personal blogs. These findings confirm future teachers’ autonomous construction of learning. Fourthly, the majority of future teachers claim to refer to fundamental scientific principles to evaluate their learning from social media and their trainers’ personal blogs. The majority of future teachers are unaware of the existence of other criteria to evaluate their learning. The expert is valued in future teachers’ epistemological beliefs. The majority prefer to refer to experts rather than to have faith in the consensus of respondents on social media and on trainers’ personal blogs. They also claim to take into consideration the opinion of those more experienced, rather than their personal experience and of that of experts. The autonomy observed in the responses of future teachers is obtained at the price of an “experimental” development of knowledge, by trial and error, through verification by way of other digital resources. The cognitive judgement of future teachers, developed with the help of digital tools, seems to be empirical.

Limitation of the study:

Our study has several methodological limitations that should be acknowledged:

Sample Limitations : A small sample (N=56) restricts generalizability, influenced by resource and access challenges. Gender imbalance (73.2% female) reflects Moroccan enrollment trends but may introduce gender-based biases in digital tool use and epistemology.

Disciplinary Skew : Overrepresentation of science/technology students (41.1%) risks disciplinary bias, as epistemological beliefs (e.g., knowledge validation) may differ across fields.

Single-Site Focus : Data from one training center (CRMEF Meknès) limits insights into regional or infrastructural variations in Morocco.

Self-Report and Design Constraints: Reliance on self-reported beliefs risks social desirability bias, while the cross-sectional design precludes tracking belief evolution over time.

Future Research Recommendations:

Mixed-Methods : Combine quantitative surveys with qualitative observations of digital evaluation behaviors.

Longitudinal Designs : Track epistemological development across teacher training and early careers.

Multi-Site/Cross-Cultural Studies : Expand to diverse Moroccan regions and global contexts to assess cultural impacts.

Experimental Interventions : Test strategies to improve critical digital literacy in teacher education programs.