Psychological and pedagogical aspects of niche tourism in the system of additional education

Автор: Arpentieva Mariam R., Gasanova Renata R., Menshikov Petr V.

Журнал: Сервис plus @servis-plus

Рубрика: Туризм

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.15, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The problem of the psychological and pedagogical meaning of tourist activity and its possibilities and limitations as an educational and psychotherapeutic activity is just beginning to become the subject of special attention. This movement is associated both with the development of tourism and psychology and pedagogy, the need for professional personnel with interdisciplinary competencies that guarantee the success of professional efforts. This movement is also associated with the development of the practice of additional education: for the (re) training of specialists in the field of tourism, its psychological and pedagogical models are important, for educational tasks in pedagogy and psychology, specialists are needed who possess innovative methods of work, knowledge and skills of assistance in human development and correction. developmental disruptions in various fields, including (niche and others types of the) tourism. Niche tourism is special interest tourism. Its appearance is connected both with the tasks of diversification and quality assurance of tourism products to ensure their competitiveness, and with the fact that tourism practice, changing and developing, is accompanied by the development of customers...

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140253891

IDR: 140253891 | УДК: 338.48+378:662+159.98 | DOI: 10.24411/2413-693X-2021-10104

Текст научной статьи Psychological and pedagogical aspects of niche tourism in the system of additional education

Submitted: 2021/02/09.

Accepted: 2021/03/09.

Introduction. The problem of the psychological and pedagogical meaning of tourist activity and its possibilities and limitations as an educational and psychotherapeutic activity is just beginning to become the subject of special attention. This movement is associated both with the development of tourism and psychology and pedagogy, the need for professional personnel with interdisciplinary competencies that guarantee the success of professional efforts. This movement is also associated with the development of the practice of additional education: for the (re) training of specialists in the field of tourism, its psychological and pedagogical models are important, for educational tasks in pedagogy and psychology, specialists are needed who possess innovative methods of work, knowledge and skills of assistance in human development and correction. developmental disruptions in various fields, including (niche and others types of the) tourism. Modern tourism is actively expanding the scope of its activities, including in the process of increasing diversification and specialization of tourism products (services and goods). One of the manifestations of this process is niche tourism as a field of tourism business and the practice of human activity, aimed at satisfying different groups of “special interests” of tourists with special motives and purposes of travel. Niche tourism is one of the leading trends in the development of modern practice and theory of tourism. Niche tourism creates significant growth in tourism, even in areas that were previously considered massive or “median”. At the same time, niche tourism practices become finds and “start-ups” for tourism of medium and mass interests, as happens, for example, with “dark tourism” (tourism of disasters and destruction), gastronomic and drug tourism, shopping tours, etc. However, niche tourism exists and is developing as a very effective and productive independent area of tourist activity of citizens and the tourist business. It exists mainly because there are such groups of motives and areas of interests and needs of clients that have not been and cannot be massive, including various elite types of tourism (many types of extreme tours, esoteric and pilgrimage tours, premium tours and services vip level, etc.). Of course, in modern tourism, the old traditions of extreme, pilgrimage, premium, etc. continue to develop qualitatively and quantitatively. tourism, however, the concept of elite one way or another means special, specific conditions and goals of activity. As a result, these types of tourism act as classic niche types of tourism. Their goals are often the harmonization of relationships with oneself and the world, clarification of relationships, self-improvement and self-realization, visiting destinations with a special history and special status in order to join the secrets of the world and increase the social, spiritual, etc. tourist status.

2021 Том 15 №1

Psychological and pedagogical aspects of niche tourism in the system of additional education

However, niche tourism does not end with elite tourism, on the contrary, it is democratic and intended for a wide variety of groups and types of tourists with special, specific interests and needs: often they are people with a relatively high and high degree of reflection and self-reflection, actively and consciously striving to saturate their needs, absent or not recognized by the bulk of people. Tourist travel in such cases often appears as a complex, health-improving and recreational (healing), cultural and educational (philosophical-esoteric) and extreme-mystical (spiritual, magical, shamanistic, etc.) travel. Self-improvement and self-realization, harmonization and clarification of relations with the world, introduction to new experience and secrets of the universe as motives of tourist activity are the criteria for advanced stages of formation and development of motivations for tourist activity, activity itself in general: a tourist of special interests is, most often, a tourist of mature , formed, conscious, clearly localized interests .. The niche type of tourism with particular clarity presupposes the work of a person with travel experience, and the organization of such work requires significant efforts on his part and on the part of the organizers of a tourist trip, therefore, not only highly qualified specialists and special high individuality, cultural and natural potential of tourist destinations [16], but also flexible, multi-component and individualized tourist routes and tourist travel programs, allowing to fulfill the special needs of clients so that this e business remained not only in demand, but also competitive, along with its more or less pronounced elitism and other specifics. It also requires a clear understanding of the socio-psychological differences between tourists of this type of tourism from tourists of mass and mixed tourism, and an understanding of the psychological and pedagogical functions of tourism, its role in human development, the role of a tourist career in the formation and development of other careers. It is also obvious that the tourism business, like any other, is undergoing a period of rethinking: the mission of the tourism business turns out to be no less significant component of its existence and development than economic and other effects, although this is often forgotten. Tourist travel acts as a bathroom sphere of a person’s self-realization, self-realization and self-development. In the context of this mission of tourism in general, niche tourism has many advantages over mass tourism.

Studies of types of tourist services and tourists, including niche tourism, are in one way or another associated with the names of many famous Westerners (R. Bachleitner, T. Burnow, E. Cohen, S. Cohen, A. T. Paul, C. Ward, W. Hanners , D. Harrison, etc.), and domestic (I. A. Gobozova, G. G.

Diligenskiy, S. V. Dusenko, G. E. Zborovsky, E. N. Pokrovskiy, V. I. Rogacheva, N. Zamyatin, S. G. Kara-Murza, V. A. Turaeva, T. I. Chernyaeva, S. E. Shcheglova and others) researchers. It is especially important to note the contribution of Z. Bauman, D. Boorstin, E. Giddens, D. MacCannell, D. Urry, A.S. Galizdra, L. A. Myasnikova, M. V. Sokolova, V. K. Fedorchenko, A. B. Fenko, E. N. Shapinskaya and other modern scientists. Tourism as a socio-cultural phenomenon has been studied and is being studied by O.E. Afanasyev, M.R. Arpentieva, O.Yu. Golomidova, L. N. Zakharova, S. N. Sychanina and many other foreign and domestic researchers. At the same time, the typological analysis of tourists and tourist programs is one of the traditional topics in tourism. Types of tourists were distinguished and described in the context of the leading problems of tourism by E. Cohen, St. Plog, F. Pearce, H. Hahn, J. Urry, E. Goffman, D. Mac-Cannel, V.A. Kvartalnov, N.I. Garanin, N.I. Kabushkin, M.A. Dybal, O. Yu. Golomidova, O. V. Lysikova, V.A. Rubtsov, E. I. Baibakov, N.M. Biktimirov and many other researchers [7; 10; 11; 12; 14; 17; 41-44]. One of the most widespread and obvious typologies is according to the types of motive or interests of tourists (Urry J., 2000 and others) [55].

The aim of the research is to study the motivation of niche tourist activity and the psychological and pedagogical functions of modern tourist activity. In our opinion, niche tourism directly or indirectly solves educational and psychological problems: training, upbringing, correction of problems of personality development and problems of interpersonal relations, as well as problems of family and work career, problems of psychological and spiritual support for the development of a person as a person, a partner and a professional. This type of tourism is addressed to tourists with a special type of needs (focused on self-exploration, self-fulfillment and self-improvement), as well as to tourists who are no longer satisfied with the traditional framework of consumption of tourist products (images), and who are looking for new areas of self-realization, need help in supporting them. Family, professional, hobby and other careers includes through building, improving, developing a tourism career.

Research results. Psychological and pedagogical analysis of niche tourism pays special attention to the problems of a tourist career and the motivation for participation in niche tourism. For the system of additional education of pedagogues-psychologists and specialists in the field of tourism are extremely important some points in improving their professional competencies. These points are the aspects related to psychological and pedagogical phenomena

2021 Том 15 №1

Психолого-педагогические аспекты нишевого туризма в системе дополнительного образования and processes, including the motivation of tourist activity and psychological types of tourists, “psychography” of destinations as “pedagogical provinces,” and “psychotherapeutic landscapes” as well as the travel career and identity of tourists [2; 14; 29; 43; 60]. Working with these phenomena is no longer within the power of a guide who does not have a special psychological and pedagogical education. For the very same psychological and pedagogical education, turning to tourism and its possibilities is a significant development of teaching and educational technologies and means.

It is appropriate here to mention actively discussed abroad, but little-known in Russia, research in the field of “pedagogy of experiences” or pedagogy of adventure / pedagogy of action / experimental learning / open pedagogy (outdoor education) or “education outside the classroom”, etc. This direction was created by K. Hahn, W. Unsoeld and other scientists and practitioners, in the context of the task of improving education and social life of a (maturing) man or woman [60]. The main directions of the pedagogy of adventure are associated with the development of relations of care / cooperation, participation / service and responsibility to people and oneself, nature and culture, as well as bodily (in sports and work) and other activities, spontaneity and comprehension of life experience, the development of the ability to create projects and independently implement them. At the same time, experiences or impressions are at the center of the pedagogical concept, being the basis for the development of experience and the whole person. The idea of testing and overcoming oneself in the conditions of “pedagogical provinces”, which can be successfully used by tourist destinations, is the main one. Education is about finding solutions in a state of danger and passing tests. Adventure as a holistic experience changes the usual course of things, routine, actualizing in a state of risk and danger (re)understanding of life and oneself in all its complexity and variability. Adventure is an experience of boundaries and an exam that strengthens the value of oneself / intrinsic value and the world, it is a path to finding oneself and to independence, the development of the ability to take responsibility, that is, the ability to set and achieve goals, the development of readiness and ability to work in cooperation, preventing conflicts and confrontation, the way to ensure the transfer (components) of life experience and the development of metasubject competencies and flexibility in building and achieving goals [60].

To summarize the views of different researchers about the features of niche tourism can be as follows. Niche tourism is — 1) not mass, but rare types of tourism; 2) types of tourism that are relatively labor-intensive and culture-intensive in creating the final product; 4) tours that combine features of various types of tourism, but focused on the main, author’s idea and a group of hobby fans; 5) relatively new types of tourism associated with secondary human needs; 6) types of tourism using non-traditional sources of financing [47; 52; 53].

For niche tourism, it is important that the high-quality market of niche tourist services in Russia is just emerging, there is essentially no real competition yet, sometimes compatriots who have settled in new countries take the initiative, who offer Russians study tours to the countries where they have moved. At the same time, the percentage of growth in niche tourism in Russia, as well as in the world as a whole, is very large every year, the number of offers increases every year literally at times.

The main motives for niche and other tourist trips are as follows:

-

• study and acquaintance with a new culture and way of life, the opportunity to stay a little in a different way of life;

-

• acquaintance with entertainment, the opportunity to visit entertainment establishments, visiting theaters, performances, festivals, carnivals;

-

• the opportunity to have fun and feel like a person with a higher social status;

-

• change of the general environment for stress relief, relaxation from difficulties, recreation and treatment, wellness goals;

-

• meeting with relatives and friends and meeting new interesting people;

-

• studying the conditions for potential business, education or other needs in the given country;

-

• shopping purposes, purchase of souvenirs and gifts;

-

• sports and experience of extreme experiences, testing oneself;

-

• spiritual development, pilgrimage and volunteering (service), etc.

In general, these motives in themselves are not narrowly specific, characteristic only of tourism of special interests. But they become such when a tourist realizes, purposefully builds and fills his travel career with specific content that corresponds to his life-meaning orientations, including his professional or educational career, family career, etc.

2021 Том 15 №1

Psychological and pedagogical aspects of niche tourism in the system of additional education

If we analyze various typologies, we will see that some of the typologies almost ignore the moment of development of the individual as a subject of tourism activity (activity), but even in the absence of special attention to the problem we are studying, even in the most traditional typologies of tourism and tourists, one can see the presence of people “who know what they want ”, seeking to spend their vacation for their own benefit and in a way that best suits their needs. These are people who choose tourist tours with special care, people with special requests for the content of tourist programs, people who are ready to take part in their development, implementation and correction, and people who are aware of themselves and their life path as an integrity, capable of cutting off what this integrity you don’t need to find what you need.

So, if we look at one of the most famous typologies of H. Hahn, we can see what distinguishes the following types of tourists [11; 12; 14]:

In general, this typology of tourists is already, in fact, outdated. Tourists for the most part are already inclined to choose active forms of recreation, and tourism itself is undergoing profound diversification and other transformations, it is developing in some directions and stagnating in others. The question of the development of tourism is one of the classical ones; practitioners and theorists have been studying it for a long time. But lately there has been more and more understanding that tourism has changed along with other spheres of services and business in general. Its development is associated with factors that previously existed, but not to the extent that they are now, as well as with factors that are new, for example, associated with digital technologies and digital nomadism (turning travel into a lifestyle), globalization and multiculturalism, problems ecology and politics (for example, the deformation of the world health care system, complete health care, as well as education and other areas of human cultural life in business), etc. The commodification and commercialization of life, multiplied by its “digitalization”, gives rise to processes of progressive “relief” of sociality, human ties are devalued and become an object of purchase and sale. “Easy sociality” as a characteristic of the modern Western world, as well as the world of relations in many eastern countries, in the countries of the former USSR, predisposes a person to the desire to “break away from everyday life”, to change relationships that do not bring satisfaction.

According to E. Amin and N. Trift, the main form of interaction between individuals in the modern world is precisely light sociality, it is structured by interactions and consumption relations, which act both as a form of self-expression of an individual and as a form of communication between people. Consumer practices as agents of light

2021 Том 15 №1

Психолого-педагогические аспекты нишевого туризма в системе дополнительного образования sociality generate ambivalent contacts (situations of consumption, encounters), which cause certain impressions in individuals who implement these practices and observe them from the outside. Easy sociality is a new form of the relationship of individuals to each other, characteristic of the townspeople, and behind them the villagers. With this form of relationship, on the one hand, there is no aggression towards another individual as a “stranger”. But, on the other hand, the perception of the individual is very limited by the tasks of consumption, it is functional, reflects the market model of relations. Solidarity between people replaces closeness and in this context means a specification for certain consumer practices (Amin A., Thrift N., 2002) [22]. This solidarity contrasts sharply with the solidarity of caring, mutual responsibility, attention to the observance of values and norms of behavior in traditional communities. This solidarity runs counter to traditional values, destroying them and the communities that share them. A person is ready to communicate with anyone, if it brings any, or better significant, consumer benefit. Likewise, a business is ready to do anything if it promises significant profits. Of course, a mass tourist is less picky about companions, a guide and the tour itself, since and to the extent that he understands the benefits of mass tourism. On the contrary, for tourists with a more developed tourist career, the issue of selectivity is one of the key ones. Travel, including tourist travel, sometimes becomes an attempt to search for a new experience of relationships, including greater significance and having greater authenticity [2; 13; 40; 48].

So in the works of D. Urry and S. Lash, two factors of tourism development are identified (Lash S, Urry J., 1987) [36]. Highlighting these factors, scientists relied on the model of M. Foucault (Foucault M., 1998) [20, p. 14-15], who thought a lot about the deformation of human / social relations in the modern world: 1) an increase in the visualization of consumption (“a person consumes images, not objects”), and, as one of the consequences, an increase in the fictitiousness of consumed services (up to religiosity in travels of the pilgrim and esoteric type, fictitious extremism in travels of the “extreme” type, fictitious elitism / professionalism in other types of tours, etc.), and 2) the development of digital (digital) communications, leading to the availability of any kind of information, patchwork a picture of the world and oneself, to curtailment of communication to the transfer of information (a communicative act in the form of a “communication test”) while cutting off the perceptual, interactive and integrative aspects of human interaction. In addition, D. Urry identifies several types of consumption / contemplation of images in tourism, including: anthropological contemplation (solitary immersion in the surrounding reality, active “passing through” images, subjective interpretation of what he saw), romantic contemplation (solitary immersion based on comprehension of new meanings that evoke a sense of awe), spectator (standard visits to “sights”, joint / collective and rapid accumulation of images of famous places), and other types of collective contemplation (habitual or inspecting).

At the same time, he describes the typical, general “mechanics” of managing attention and, thus, the behavior (choice and consumption of a tourist product) of a tourist, a specific template of tourist marketing, which includes a number of steps (Urri J., 2005, etc.) [18; 19; 55]: the selection of a “unique object”, the selection of the “specific” or “typical” in it, the selection of the “unknown” in the “known”, the selection of the “normal” in the “unusual”, transfer of the familiar into the unusual (visual) context and confirming the extraordinary objects ... This process of “motivating” customers is inherently purely manipulative, that is, it offers the client a fiction (events and other pseudo-events and pseudo-objects) hidden behind the “behind the scenes” of marketing manipulations.

E. Goffman (2019), D. MacCannell (2000) formed a “theory behind the scenes” and identified several “plans of social reality” in it: the front — the hall or the outside, and the background is “behind the scenes” as the reverse side of the process, inaccessible to the consumer Tourists-spec-tators are always in the foreground, performers are local residents, staff serving tourists, outsiders are people who are not involved in the interaction of the first and the second [8; 15; 38]. Spectators are interested in admission and have the illusion of access to the backstage, and the performers — in creating hoaxes, deceptions: romanticizing tourist places, inventing “unique” monuments or “pseudo-events” invented specifically for tourists attractions, serving as a source of income for local residents (Boorstin DJ, 2012) [23]. Plan of reality is the unique monuments and real villages of the aboriginal tribes, real temples, etc., to which, however, tourists often do not have access. D. McCanell (1973 and others) introduced the concept of “staged authenticity” [38]. He wrote that the tourist is looking for “the authenticity of the world”, he singles out the sublayers: what the tourist runs from (“the appearance of reality” that is, the usual, routine life); artificial front “tourist” plan; “a slightly open background” is the tourist’s admission to the essence; “not quite an authentic background” access to which changes the meaning of the image and the structure of behavior;

2021 Том 15 №1

Psychological and pedagogical aspects of niche tourism in the system of additional education

“background of reality” is a genuine unprepared reality that creates a “behind the scenes” of events and the main motivation for tourists [15; 38]. Authenticity in tourism is usually “staged” (MacCannell 1975, and other), that is, it is established by a performative act that emphasizes what is to be looked at and hides contradictions or negative aspects. Tourists strive to understand the background of social reality, “behind the scenes” of everything that happens, while avoiding “pseudo-events”. Tourists participate in a collective ritual of “viewing” or “finding”, identifying themselves as a group that explores this or that phenomenon as an object (mass or non-mass) tourist.

D. Boorstin (Boorstin D., 1973; Boorstin D., 2012) and E. Cohen (Cohen E., 1979; Cohen E., 2003; Cohen E., 2010) proceed from the factor of the aspirations of tourism actors to understand reality, her research and transformation of her own life world [4; 23; 24; 25; 26; 46]. Because of this, they separate “tourists” and “travelers”. The former are satisfied with both pseudo-events and entertainment of simulated reality, visual consumption is enough for them, they are passive and do not seek authenticity; they seek entertainment and thoughtless rest. Travelers, on the contrary, are active, interested in new experiences, exploring the world around them and looking for the meaning of reality, authenticity / transparency. There is an experienced one here, looking for this meaning, traveling the world, treating it aesthetically. Experimental tourists perceive new things through involvement in the life of another people, place and time: through a new culture and nature. They often fall into the background or third place (MacCannel D., 2016), trapped in an imitated, falsified reality, for example, religious tourists experiencing culture shock from the kind of “real life” of a sacred place [15]. The most “conscious” type of travelers is existential. He or she has knowledge about himself, his or her values, the meaning of life, striving to get close to them, motivating himself / herself or helping himself to get out of the “comfort zone” through travel.

N. Graburn (Graburn N., 1989) drew a parallel between making a tourist trip and a religious sacrament with its rituals and elements, opposing “tourists” to “travelers” [31; 32]. Thus, “outside tourists” are not interested in local culture, but observe neutrality; “generators of pseudo-events” are the interested in the search for authenticity, but content with multiple pseudo-events; “neo-colonialists” are the expect the natives to satisfy their own needs at their expense; “sources of problems” are the infantile subjects striving for everything forbidden and promoting their views; “enemies” are those who reject the culture and customs of the inhabitants (up to aggression). T. Abankina and N. Graburn believe that the change in the concept of tourism from passive-comfortable to active-extreme is associated with a shift in the focus of social motivation and consumer behavior in the field of culture (Abankina T., 2005; Graburn N., 1998) [1; 31; 32]. The new type of culture consumers does not have preferences and constantly violates the boundaries, the border between elite and popular culture is mobile, modern culture is changeable, components of all existing cultures are included in the preferences of tourists, therefore the same subject can make a number of completely different journeys. J. Gold is close to them in his conclusions (Gold J. 1990) [6, p. 45]. He also described two types of motivations for tourism: the motivation to overcome obstacles (reduce tension) and the motivation of fresh sensations (to increase tension. In his opinion, tourism is a sphere of consumption, the purpose of which is to satisfy the corresponding needs for comfort / reproduction / survival and development. Thus, this consumption can be passive (which is more typical of mass tourism) and active (which is more typical of niche tourism).

Tourism activity includes a set of role models, within which all kinds of needs are manifested to one degree or another. As a result, sociological and psychological approaches to tourism agree on the importance of taking into account the values and motives of tourists, as well as those role models in which these motives and values are expressed. One of the examples of this typology is presented in the study by O.Yu. Golomidova (2019) [7]. Modern tourists, in her opinion, can be divided into types depending on their attitude to urban culture, as well as the motives “pushing” them out of the city or, on the contrary, attracting them to it: 1) escapists (seekers of peace, seekers of peace of mind, seekers of freedom , seekers of “exotic”); 2) fans of “civilization”, “urbanists”; 3) “collectors of impressions”, “spectators”; 4) “deep” tourists seeking to reflect on themselves and the world, including in the context of tourism practice [7]. For different types of tourists, their travel motives, as well as their preferred types, directions, forms of organization will be significant. Of course, there are also tourists among rural residents, however, there are usually fewer of them, since, in addition to the often lower (economic) standard of living, they have less deficit of contact with nature, less manifestation of event, labor and other deprivation. The villagers do not have the state of fatigue described by J. Baudrillard, associated with the lack of work and the ability to change something in their life and the life of society [3], they also do not have such a pronounced progressive

2021 Том 15 №1

Психолого-педагогические аспекты нишевого туризма в системе дополнительного образования isolation within families and in other, labor, friendly, neighbor and other types of the relationships. Joint and extensive work brings feelings of self-efficacy and social efficiency, reduces consumer motives and grounds for interaction, understanding of oneself and the world, and also encourages a full-fledged semantic exchange, and not its simulation in an urban, “digitalized” environment. Accordingly, these tourists behave differently, although there are not so many special studies on this topic, but it can be assumed that this group of tourists is more selective in their choice and behavior in relation to tourist trips, has different, in comparison with the townspeople, systems of motives of life , including in relation to travel.

Understanding of the existence of differences between tourists, not reducible to external factors, led to the active penetration of psychological and pedagogical concepts into tourism. Thus, in the practice and theory of tourism, a number of socio-psychological and socio-pedagogical and similar motivational theories are used: A. Maslow’s theory of the hierarchy of needs, the theory of travel career ladder (TCL) F.L. Pearce (Pearce Fh. L., 1993) [34; 41; 42], theory of optimal motivation S. E. Iso-Ahola (Iso-Ahola S.E., 1982) [35], allocentric-psychocentric theory St. Plog (Cruz-Milán, O., 2017; Plog St., 1974) [28; 43; 44] and a number of others (Cohen, E., 2003; Cohen, E., 2017; Lowry L.L., 2017; Prince, S., 2017 and others) [24; 25; 26; 46].

So, according to the theory of the hierarchy of needs by A. Maslow [39], there are five groups of needs that form the hierarchy levels from basic vital, “lower” to “higher”, social interpersonal, personal and professional: physiological is vital needs and needs of reproduction, shelter, reproduction; safety is stability, security / comfort and certainty / structuredness, comprehensibility, belonging to society; love is belonging, involvement and affection, care; respect is successes and achievements, high self-esteem and social assessment / self-efficacy and social effectiveness; self-actualization and self-realization and self-improvement / personal, interpersonal, professional growths. A. Maslow suggested that a person is motivated to meet higher needs only if lower needs have already been satisfied [39]. This concept has become the basis for many other modern researches on motivation, including research in tourism. But, the problems of this model are little discussed; however, historical and modern examples show that for a person, first of all, the meanings of his life, the highest values and motives that make him a person are important. And if a man or woman can “endure” the dissatisfaction of basic needs, then the refusal or impossibility of satisfying higher needs leads to the spiritual death of a man or woman. This can be seen both in ordinary examples, when a man or woman is “overboard” of social life (loses his / her family, job, etc.), and in extreme examples (Frankl V., 2020, etc.) [33], including the experience of survival in concentration camps, isolation, etc. Unfortunately, even the opinion of V. Frankl, who divides people into two races (decent and dishonest), is not taken seriously into account when discussions about the level of development of human beings arise. However, even this hint contains some points that indicate that we are really two different “racial” types of people. This is not just a “crowd man” and an “outsider”, it is a more serious and ambiguous difference summed up by Russian scientists B.F. Porshnev and B. Didenko (Didenko B., Boykov M.V., 2010) in their concept of human races [9]. Racial and, especially, cultural differences of tourists, of course, become focuses of attention (the most actively traveling Russian tourists, American tourists, tourists from China and Japan, tourists from Israel, etc. are often studied), however, they are not considered so seriously. In our opinion, this is a promising, promising topic for a separate large study, including in the context of allological or xenological studies and works on the problems of human races and human origins. Within the framework of this understanding, it is not necessary to say that tourists in a niche cluster, in contrast to tourists in a mass cluster, are distinguished by an orientation towards higher needs. It should be said that these tourists have these needs in the first place in their individual value system.

-

A . Maslow’s model [39] is adjoined by studies using the model “Formulas of happiness / PERMA” (happiness) from the positive psychology of M. Seligman (Huang, K., Pearce, Ph., Wu, M.-Y. & Wang, X ., 2019; Seligman, MEP, 2012) [34; 49]. As you know, M. Seligman (Seligman, M. E. P., 2002, 2010) identifies three steps on the path to happiness: 1) achieving a comfortable and pleasant life (superficial happiness); 2) a dignified life in which the individual is focused on working out his own strengths and achieving a state of flow; 3) a life filled with meaning, in which a person seeks to achieve the highest goal (which is to serve others, the world) [49; 50].

The PERMA model (Seligman, M. E. P., 2012) [49] is based on five motivational dimensions that are significant in the organization of human activity:

-

• positive emotions / joy or “fun (positive emotion, the ability to enjoy life here and now, to see the past, present and future from a positive point of

2021 Том 15 №1

Psychological and pedagogical aspects of niche tourism in the system of additional education view or optimism, to positively (re) define events, to enjoy large and small joys of being, while achieving pleasure as satisfaction and a sense of fulfillment from the performance of an action, etc.);

-

• meaningfulness / search for meaning (meaning — the meaning that a person finds in life, causes the desire and need to live / survive / cope with difficulties / strive for something, following a reason that is greater than the person himself);

-

• harmonious, balanced and reliable, positive relationships (positive relationships as positive and meaningful relationships of trust, acceptance, respect, closeness, care, feeling of belonging and reference, etc.);

-

• engagement or pleasure from activity (engagement as interest and stay in the flow: time seems to stop, a person loses a sense of himself and completely concentrates on the present, this is an occupation that captivates a person);

-

• achievements (accomplishment / achievement — setting goals / ambitions, recognition and success, a sense of pride in what has been done and achieved, striving for growth and self-improvement).

The theory of Fh. Pearce (Pearce Fh., 1982-2020) describes the career of a traveler: his tourist and other types of travel form a journey up the career ladder, a career of a traveler. Pierce’s career ladder is based on the hierarchy of travel motives and is built on the model of A. Maslow [34; 41; 42]. Each person has a “travel career” similar to their “work career”. People start their tourism careers initially at different levels of their development. During his travel career, while gaining travel experience according to TCL theory, a person increases the level of motivation. Travel decisions and decision-making processes are not static; they change throughout a person’s life depending on his travels and other life experiences. Also Fh. Pearce noted the differences between tourists and travelers, highlighting the system of describing typical tourist roles, which are different from the types of roles that are not typical for tourism, but are associated with travel in general. He identified five concepts of travel: environmental — close encounter — spiritiual — pleasure — business. However, now the differences between the tourist and the traveler are changing.

Fh. Pierce identifies the following stages of development of tourist needs (from the highest to the lowest): 1) satisfying the needs for self-actualization and for the experience of flow / creativity of relations with the world of people and objects; 2) meeting the needs to maintain high self-esteem / development needs: a) aimed at others: the need for status, the need for respect, recognition, the need for achievement; b) self-directed: the need for self-development, the need for growth, the need for mastery or controlling competence, the need for self-efficacy; 3) satisfying relationship needs: a) aimed at others: the need to reduce anxiety about others, the need to join (turn on);b) directed at oneself: the need to give love, affection, care; 4) meeting security / security needs: a) directed at others. related to others: the need for security from others, the need to have their own time and space / boundaries from others; b) self-related: the need to reduce anxiety, the need to predict and explain the world; 5) meeting the needs for relaxation: a) externally oriented: the need for escape from reality, internal and external arousal (drive and stimulation), curiosity; b) internally oriented: needs for rest, food, drink (vital), relaxation (control of the level of arousal) [40; 41]. In general, Fh. Pearce argues that people tend to climb the travel ladder as they become more experienced travelers. Higher-level mo-

2021 Том 15 №1

Психолого-педагогические аспекты нишевого туризма в системе дополнительного образования tives that are neither shared nor guided by include low-level motives. Tourism can therefore be seen as a developmental practice. However, it does not always become or is not always, since some types of tourism and some tourist operators consciously or unconsciously exploit mainly the “low” needs and motives of customers. Lower-level motives must be satisfied or tested before higher-level motives come into play. But, nevertheless, any journey requires a ladder, assuming the prospects for the development of a person as a person, a partner and a professional.

The next model is the theory of optimal excitement or the theory of search and escapes (stimulation), also called the two-dimensional theory of tourist motivation, developed by S.E. Iso-Ahola [35]. The basic principle behind the theory of optimal arousal is that a person seeks the level of stimulation that works best for him / her as a person, partner and professional. If a individual’s life is “too quiet” and motionless, he or she may look for incentives to change through activity. If there are too many things happening in the person’s world, he tries to turn off the stimulation and find a calmer environment. Tourism is an excellent means of meeting human needs for the optimal level of stimulation. Someone whose daily life is domineering may choose a secluded and peaceful place to withstand pressures at home and at work. Someone whose work and life are boring may want to take a vacation that brings adventure and excitement (Iso-Ahola, S. E., 1984) [35].

Another very impotent in tourism studies theory is St. Plog’s psychocentric-allocentric model (Plog, St., 1973-

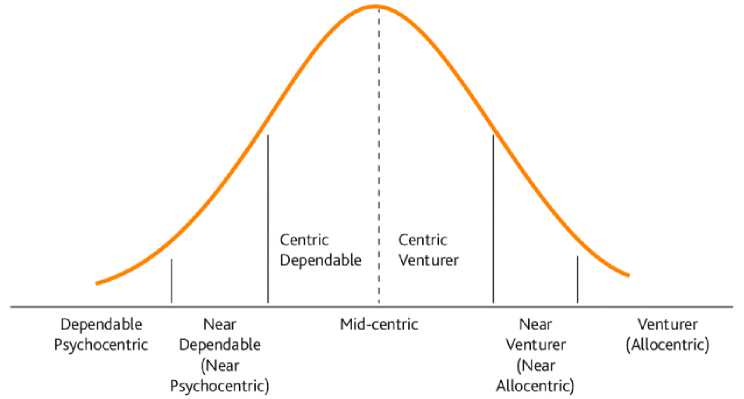

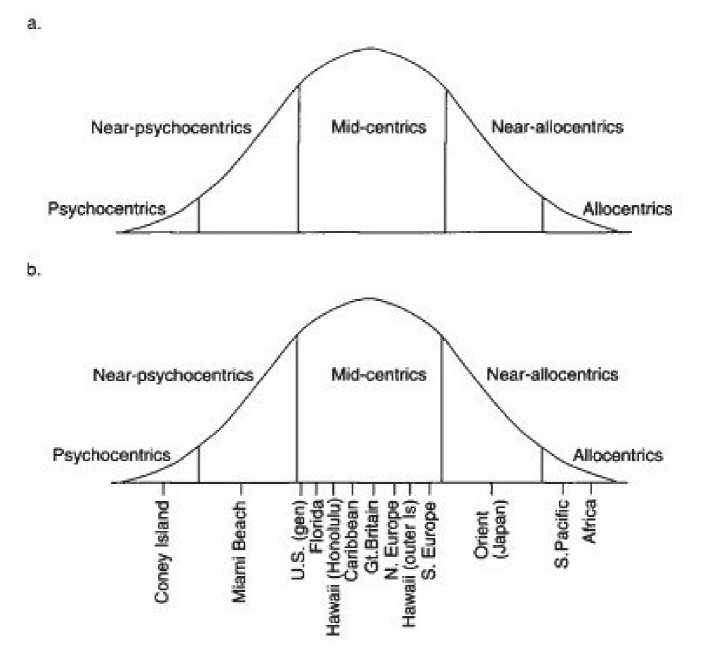

2004; Cruz-Milán, O., 2017) [28; 43; 44]. This model is very important in the development of a unified theory of travel motivation. St. Plog (1973-2018) published one of the first “psychographic” scales of types of tourists, it includes several types (psychocentrics — near psychocentrics — mid-centrics — near allocentric — allocentrics). At one end, the psychographic scale includes individuals traveling alone or with a partner or friend. Such travelers tend to leave their own routes and travel at their own rhythm and pace, they want to be independent and active, tend to avoid typical tourist sites and take an interest in the local population and its culture, as well as nature and its inhabitants) .These people usually trying to move away from standards, they can be called the allocentric part of the lifestyle scale. The other end of the scale is a profile of people who do not want any problems before or during their vacation, they like to have everything organized for them, and they want total relaxation. They take care of their own body and therefore their interests are in the areas of relaxation, health care and / and beauty. They do not show much interest in the locals or their culture, as well as in nature, he is psychocentric. There are three more intermediate groups, a total of five: close to psychocentric, middle and close to allocentric. Recently the typology has been changed and the dimension of traditionalists — sightseers and travelers — pioneers is added. Most tourists are located between these extremes, so the differences between “mass” tourists on both sides of the center are small, may not be noticeable, and change (Figures №1,2).

Figure №1. Psychographic types of tourists (Plog, St., 1991, 2001, 2004)

2021 Том 15 №1

Psychological and pedagogical aspects of niche tourism in the system of additional education

Figure №2. Psychographic types travel offers / destinations and tourists (Plog, St., 1991, 2004) [43; 44]

St. Plog proposes a breakdown of travel offers (and destinations) and tourists by psychological segment, highlighting five main personality types and types of travel products. For this, St. Plog (Plog, St., 1973) used a psychometric scale to classify tourists into allocentric, midcentric and psychocentric, depending on the individual’s relative orientation to their culture and the culture they visit. Psychocentric tourists like good facilities; good pools; well organized trip; dinners in the pub. They do not seek to leave their comfort zone. Allocentics, on the other hand, are interested in new experiences and new cultures. The personality scale helps explain why the popularity of destinations rises and falls. In particular, the personal characteristics of tourists determine the nature of their travels and preferences. The psychocentric person is conservative about travel and prefers “safe” directions. The allocentric person loves adventure, preferring “new” directions and discovering these new directions (Plog, St., 2001) [43].

Another model is suggested by Er. Cohen. Er. Cohen proceeds from the phenomenological distinction that tourists let go of the orientation of their everyday world and focus on the other and unknown Tourist travel is a specific interweaving of alienation from everyday life and longing for another place / time. The degree to which a person tends to separate from the familiar world (“center”, center) and join the world elsewhere (“center-out-there”, center-out-there) can vary significantly and lead to a “continuum” of experiences ... The needs and motives underlying travel differ greatly among (potential or real) tourists, which indicates the importance of psychological distance from the usual world in tourism, but only just physical one [25-27]. In E. Cohen’s theory, there are several types of tourists (Table №1).

Let’s give the examples of comparison of tourist typologies (table №2).

2021 Том 15 №1

Психолого-педагогические аспекты нишевого туризма в системе дополнительного образования

Table№1. Types of tourists in E. Cohen’s model (Cohen, E., 2003) [24].

|

Tourist roles between familiarity and novelity |

|

|

Institutionalized tourists / Институционализированные туристы Dealt with routinely by the tourism industry — toor operators, travel agents, hoteliers and transport operators |

Non-institutionalized tourists/ Неинституционализированные туристы Individual travel, shunning contact with the tourism industry except where absolutely necessary |

|

Organized mass tourist / Организованный массовый турист Low on adventurousness he / she is anxious to maintain his / her environmental bubble’ on the trip. Typically purchasing a ready-made package tour of-the-shelf, he / she is guided through the destination having little contact with the local culture or peoples |

Researcher, explorer / Исследователь The trip is organized independently and is looking to get off the beaten track. However, the comfortable accommodation and reliable transport are sought and, while the environmental bubble is abandoned on occasion, it is there to step if things get tough. |

|

Unorganized mass tourist, individual mass tourist / Неорганизованный массовый турист Similar to the above but more flexibility and scope for personal choice is built in. However the tour is still organized by the tourism industry and the environmental bubble shields him / her from the real experience of the destination |

Tramp, drifter / Бродяга All connection with the tourism industry are spurned and the trip attempts to get as far from home and familiarity as possible. With no fixed , he drifter lives with the local people, paying his / her way and immersing him/ her their culture. |

Table №2 . Examples of comparing tourists

Список литературы Psychological and pedagogical aspects of niche tourism in the system of additional education

- Abankina, T. (2005). Ekonomika zhelaniy v sovremennoy tsivilizatsii «dosuga» [The economy of desires in the modern civilization of "leisure"]. Otechestvennyye zapiski [Domestic notes], 4 (25), 115-123. (In Russ.).

- Arshinova, V.V., Tokar, O.V., Kuznetsova, N.V., Arpentieva, M.R., Kirichkova, M.E., Novakov, A.V. (2018). Trevel-psik-hoterapiya ili psikhoterapevticheskiy turizm [Travel-psychotherapy or psychotherapeutic tourism], Servis vRosslllza rubezhom [Service in Russia and abroad] 3, 6-24. https://doi.org/10.24411.1995-042X-2018-10301 (In Russ.).

- Baudrillard, J. (2006). Fatigue. In: Baudrillard J. Consumer Society. Its myths and structures. Moscow: Publishing House Cultural Revolution; Republic, 230-234. (In Russ.).

- Brazales, D. F. H., Tapia, P. J., & Koroleva, I. S. (2020). Alternative tourism as a type of sustainable tourism. Research Result. Business and Service Technologies, 6 (2), 2020,3-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.18413/2408-9346-2020-6-2-0-1. (In Russ.).

- Boorstin, D. (1993). Amerikantsy. Demokraticheskiy opyt [Americans. Democratic experience] Moscow: Progress Pub., Litera Publ., 1-832. (In Russ.).

- Gold, J. (1990). Osnovy povedencheskoy geografii [Basics of Behavioral Geography], Moscow: Progress Publ., 1-304. (In Russ.).

- Golomidova, O.Yu. (2019). Turizm kak fenomen kuitury. Avtoreferat dissertatsii kandidata kul'turologii.[Tourism as a cultural phenomenon. Abstract of the dissertation of the candidate (PhD) of cultural studies], Yekaterinburg: Humanitarian University Publ., 1-20 (In Russ.).

- Goffman, E. (2019). Total'nyye instituty: ocherki o sotsiainoy situatsii psikhicheski bol'nykh patsiyentov i prochikh postoyal'tsev zakrytykh uchrezhdeniy [Total institutions: essays on the social situation of mentally ill patients andother guests of closed institutions] Moscow: Elementary forms Publ., 1-464. (In Russ.).

- Didenko, B. A., Boykov M. V. (2010) Chto yest' chelovek? Osnovnoy vopros [ What is man? The main question], Moscow: Consciousness Publ., 1-260. (In Russ.)

- Dybal, M.A. (2009). Al'ternativnyye priznaki tipologii turizma [Alternative signs of tourism typology], Vestnik INZHEK-ONa. Seriya: Ekonomika [INZHEKON Bulletin. Series: Economics] 3, 388-391. (In Russ.).

- Kabushkin, N.I. (2006). Menedzhment turizma [Tourism management], Minsk, Belarusian State Economic University Publ., 1-214. (In Russ.).

- Kvartalnov, V.A. (2002). Turizm [Tourism] Moscow: Finance and Statistics Publ., 1-320. (In Russ.).

- Korobchenko, A.I., Golubchikov, G.M. Arpentieva, M.R. Psikhologo-pedagogicheskiye vozmozhnosti i ogranicheniya giempinga: turizm kak praktika razvitiya cheioveka. Psychological and pedagogical possibilities and limitations of glamping: tourism as a practice of human development. Fizicheskaya kul'tura. Sport. Turizm. Dvigatel'naya rekreatsi-ya [Physical culture. Sport. Tourism. Motor recreation], 5, 4,134-140. (In Russ.).

- Lysikova, O. V. (2012). Russian tourists: types of identity and social practices. Sociological Research, 4 (336), 136143. (In Russ.).

- MacCannell, J. (1976/2013). The Tourist. A new theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Schoken Books, 1-280.

- Malysheva E.O. (2020). Teoreticheskiye podkhody v izuchenii turistskoy destinatsii. [Theoretical approaches in the study of tourist destinations], Vestnik Buryatskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta [Bulletin of the Buryat State University] 1, 60-65. (In Russ.).

- Rubtsov, V.A., Baibakov E.I., Biktimirov N.M. (2020) Psikhograficheskiye tipy turistov i sootvetstvuyushchiye im mar-shruty [Psychographic types of tourists and their corresponding routes]. In: Zyryanov A.I., Subbotina T.V., Kopytov S.V. (eds.). Tsifrovaya Geografiya. Materialy Vserossiyskoy nauchno-prakticheskoy konferentsii s mezhdunarodnym uchastiyem. V 2-kh tomakh [A Digital Geography. Materials of the All-Russian scientific-practical conference with international participation. In 2 volumes ]. Perm: Perm State National Research University Publ., 174-177. (In Russ.).

- Urry, J. (2005). Vzglyad turista i globalizatsiya. Tourist perspective and globalization. Massovaya kul'tura: Sovremen-nyye zapadnyye issledovaniya [Popular Culture: Contemporary Western Studies], Moscow: Pragmatics of Culture Publ., 136-150. (In Russ.).

- Urry, J. (1996). Turisticheskoye sozertsaniye i «okruzhayushchaya sreda» [Tourist contemplation and the "environment"]. Sociological Issues, 7, 70-100 (In Russ.).

- Foucault, M. (1998). Rozhdeniye kliniki [The birth of the clinic], Moscow: Meaning Publ., 1-310. (In Russ.).

- Akinci, Z.&Kasalak, M. (2016). Management of Special Interest Tourism in Terms of Sustainable Tourism. In: Avcikurt C., Dinu M.S., Hacioglu N., Efe N., Soykan A., Tetik N. (eds.) Global Issues and Trends in Tourism. Sofia: St. Kliment Ohridski university press, 177-190.

- Amin A., Thrift N. (2002). Cities: reimagining the urban. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1-192.

- Boorstin D. J. (1961/2012). The Image: AGuide to Pseudo-Events in America. N. Y.: Harper & Row, Vintage, 1-393.

- Cohen, E. (1979). A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences. Sociology, 13, 2,179-201.

- Cohen, E. (2003). The Sociology of Tourism: Approaches, Issues, and Findings. Annals of Tourism Research. 10, 373-392. 10.1146/annurev.so. 10.080184.002105.

- Cohen, E. (2010) Tourism, Leisure and Authenticity, Tourism Recreation Research, 35, 1, 67-73, http://dx.doi.org/10. 1080/02508281.2010.11081620

- Cruz-Milán, O. (2017). St. Plog's Model of Typologies of Tourists. In: The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Travel & Tourism. New York: SAGE Publications, 954-956, http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483368924.n356

- Elands, B.& Lengkeek, J. (2012). The tourist experience of out-there-ness: Theory and empirical research. Forest Policy and Economics, 19, 31-38, http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.forpol.2011.11.004.

- Gisolf, M. (2017). The Tourist's Profile and Lifestyle. Tourism theories, January 16. Tourist Profiles and Sustainability, 1. URL: http://www.tourismtheories.org/?p=999

- Gnoth, J., Mateucci X. (2014). A Phenomenological Organization of the Tourism Literature. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8(1), 3-21.

- Graburn, N. (1998). The Ethnographic Tourist. In: Dann Gr. (ed.). The Tourist as a Metaphor of the Social World. Wallingford: CAB International, 19-39.

- Graburn, N. (1989). Tourism as the Sacred Journey. In: Smith V. (ed.). Hosts and guests. The Anthropology of Tourism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 21-36.

- Frankl, V. (2020) Man in search of meaning Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything. New York: Beacon Press, 1-130.

- Huang, K., Pearce, Ph., Wu, M.-Y. & Wang, X.-Zh. (2019). Tourists and Buddhist heritage sites: An integrative analysis of visitors' experience and happiness through positive psychology constructs. Tourist Studies, 19 (4), 549-568, http:// dx.doi. org/10.1177/1468797619850107.

- Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1984). Social psychological foundations of leisure and resultant implications for leisure counseling. In: Dowd Е. Т. (ed.). Leisure counseling: concepts and applications. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 97-125.

- Lash, S, Urry, J. (1987/2014). Economies of Sign and Space. L: Sage, 372p. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446280539

- Ma, S., Kirilenko, A., & Stepchenkova, S. (2020). Special interest tourism is not so special after all: Big data evidence from the 2017 great American Solar Eclipse. Tourism Management, 77, 1-13. https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.tour-man.2019.104021.

- MacCannell, D. (1973). Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. American sociological review. 79 (3), 589 — 603

- Maslow, A. (2019). Motivation and Personality. New York, NY: Harper, Deli: Prabhat Prakashan, 1-200p.

- Menshikov P.V., Kuznetsova N.V., Korobchenko A.I., Golubchikov G.M., Arpentieva M.R. (2020). Psychological and pedagogical aspects of glamping: tourism as a practice for personal development. Service and tourism: current challenges, 14(2), 38-49. https://doi.org/10.24411/1995-0411-2020-10204

- Oktadiana, H. &Pearce, Ph. &Pusiran, A.&Agarwal, M.(2017). Travel Career Patterns: The Motivations of Indonesian and Malaysian Muslim Tourists. Tourism Culture & Communication, 17, 231-248. http://dx.doi.org/10.3727/10983041 7X15072926259360.

- Pearce, Ph.L. & Lee, U. (2005). Developing the Travel Career Approach to Tourist Motivation. Journal of Travel Research, 43. 226-237. 10.1177/0047287504272020.

- Plog, St. (2001). Why destination areas rise and fall in popularity, Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 42, 3,13-22.

- Plog, St. C. (1972/2004). Leisure travel: A Marketing Handbook. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 1-272

- Postma, A., & Schmuecker, D. (2017). Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: conceptual model and strategic framework. Journal of Tourism Futures, 3(2), 144-156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JTF-04-2017-0022.

- Prince, S. (2017). E. Cohen's Model of Typologies of Tourists. In: Lowry L.L. (ed.) The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Travel and Tourism. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc Sage, 957-968, http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4135/9781483368924. n 109.

- Rittichainuwat B. N. (2018). Special Interest Tourism. Newcastle, PA, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 1-311 .

- Santayana, G. (1995/2017). The Philosophy of Travel. In: Santayana, G. The Birth of Reason and Other Essays. NY : Columbia University Press, Open Road Media, 5-18.

- Seligman M. (2010/2012). Flourish: Positive Psychology and Positive Interventions (The Tanner Lectures on Human Values). Michigan: University of Michigan, Free Press, 1-368.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic Happiness. New York: Free Press, 1-349.

- Seraphin, H., Sheeran, P., & Pilato, M. (2018). Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9, 374-376. http://dx.doi.Org/10.1016/j. jdmm.2018.01.011

- Agarwal Sh., Busby Gr., Huang R. (eds.) Special Interest Tourism: Concepts, Contexts and Cases.. Oxon: CABI, 2018. 236

- Sharpley, R. (2014). The consumption of tourism. In: Sharpley, R., Telfer, D.J. (eds.). Tourism and development: concepts and issues. Clevedon: Channel View Publications, 358-366

- Trauer, B. (2006). Conceptualizing special interest tourism—frameworks for analysis. Tourism Management, 27 (2), 183-200. https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.10.004

- Urry J. (2000). Sociology beyond Societies. Mobilities for the twenty-first century. London; N-Y.: Routledge, 1- 268.

- Van Zyl, U.E. (2013). M. Seligman's flourishing: An appraisal of what lies beyond happiness. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 39 (2), #1168, 3p. http://dx.doi.org/39.10.4102/sajip.v39i2.1168.

- Weaver, D. (1999). Magnitude of Ecoturizm in Costa Rica and Kenya. Annals of Tourism Research, 4, 792-816.

- Wong, P.T.P (2011a). Positive psychology 2.0: Towards a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology 52(2), 69-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0022511

- Wong, P.T.P. (2011b). Reclaiming positive psychology: A meaning-centered approach to sustainable growth and radical empiricism. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 50, 248-255.

- Weiftbach V. (2008). Die Erlebnistherapie von KurtHahn als Vorreiter der Erlebnispadagogik. Halle-Wittenberg: Munich, Germany: GRIN Publishing, 1-84.