Simultaneous Interpreter Professional Competence in a Cognitive and Discursive Paradigm

Автор: Korovkina M.Ye.

Журнал: Вестник Волгоградского государственного университета. Серия 2: Языкознание @jvolsu-linguistics

Рубрика: Материалы и сообщения

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.23, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The paper presents a simultaneous interpreter professional competence that consists of three components – communicative, extralinguistic and procedural or specialized (sub)competences. It is focused on the third component, which includes the abilities of inferencing, probabilistic forecasting and compression, specifically required for simultaneous interpreting (SI). Inferencing is a two-staged process of retrieving assumptions with regards to composing invariant senses, which means deriving inferences of the message in the source language (SL) and generating implicatures in the target language (TL). Probabilistic forecasting is based on the analysis of the invariant sense prompts in the SL message and boils down to anticipating invariant sense evolvement in the context. It is closely related to compression – an ability to eliminate the redundant information and to condense the retrieved invariant sense in the SI for linguistic and extralinguistic reasons, such as interlanguage asymmetries between the source and target languages and an acute shortage of time because of the speaker's speed. Moreover, compression is one of the key discursive strategies used by the simultaneous interpreter in speech production. These information processing abilities stand for the SI inherent cognitive features or mechanisms and cognitive-and-discursive strategies employed by the simultaneous interpreter in order to meet the pragmatic needs of a SI communicative situation. Descriptive, comparative, model simulation, introspection and observation methods were used for the research task realization. The outcomes of the study show that the above mentioned three cognitive mechanisms, discursive strategies and abilities closely interact in the SI; it is manifested through inferences and implicatures generated on the basis of presuppositions. Relying on his/her professional competence and employing discursive strategies of inferencing, probabilistic forecasting and compression, the simultaneous interpreter chooses the adequate language means to render invariant sense in its transition from the source to target languages. The choice is facilitated by presuppositional knowledge rooted in the worldview of the source and target languages, constituting the simultaneous interpreter's language and conceptual thesauri. Another important factor assisting SI cognitive processes and the choice of discursive strategies is the analysis of text functions that makes it possible to elicit presuppositions helpful for inferencing and probabilistic forecasting.

Simultaneous interpreting, competence, inferencing, probabilistic forecasting, compression, inference, implicature, presupposition

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149145976

IDR: 149145976 | УДК: 81’253 | DOI: 10.15688/jvolsu2.2024.2.12

Текст научной статьи Simultaneous Interpreter Professional Competence in a Cognitive and Discursive Paradigm

DOI:

Citation. Korovkina M.Ye. Simultaneous Interpreter Professional Competence in a Cognitive and Discursive Paradigm. Vestnik Volgogradskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Seriya 2. Yazykoznanie [Science Journal of Volgograd State University. Linguistics], 2024, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 158-171. DOI: 2024.2.12

Simultaneous interpreting (hereinafter – SI) is an area of great interest for researchers, as it offers significant psychological and cognitive challenges. The greatest challenge is the speed of information processing, which is imposed by external factors (speaker’s speed and information linearity) while an interpreter is simultaneously involved in two speech activities. Attempts to understand better the SI cognitive specifics have been extensively made since the first high-profile use of SI at the Nuremberg process. Below follows an overview of the research studies on the subject.

Interpreting as a discursive activity can be described both as process and its outcomes and results. The analysis of SI as a process includes all stages of information processing and sense interpretation – understanding, sense analysis in the source language (hereinafter – SL) and search for linguo-specific means in the target language

(hereinafter – TL) to convey the invariant sense of the SL message/text. The interpreter’s solutions are the outcomes of the interpretation process and the interpreter’s choices.

SI was studied initially in the frame of linguistics, psycholinguistics, and psychology; at present, its academic description has widened to cognitive linguistics and neurosciences. Moser-Mercer singles out the two most important SI research paradigms: natural sciences and liberal arts [Moser-Mercer, 1994]. The first paradigm focuses on the research of brain functions and cognitive mechanisms of information processing [Gerver, 1975; Massaro, 1975; Moser, 1978; Lambert, 1988; Shlesinger, 2000]. The liberal arts paradigm views interpreting as a process and text analysis given to its discursive (pragmatic and cognitive) features. It is represented mostly by the Paris school [Seleskovitch, 1998; Lederer, 1981; Déjean Le Féal, 1991]. Researchers of the German school of thought do SI research in the frame of the communicative-and-cognitive paradigm [Pöchhacher, 1995; Kalina, 1992]. Representatives of these two paradigms have made an important contribution to SI research, and many of their 20th-century insights are still valid today.

One of the first universal models of translation as a process was designed by the Soviet psycholinguist Zimnaya who singled out three stages in the translation/interpreting process: 1) comprehension of the text in the source language; 2) switching over to the target language; 3) production of the text in the target language [Zimnaya, 1978, pp. 43-45].

As is often the case in research, other researchers worked along the same lines. For example, Shiriayev described the SI model as a three-stage process consisting of nearly the same phases, with slightly different terminology: 1) comprehension of the text in the source language; 2) search for translation decisions; 3) production of a text in the target language [Shiriayev, 1979, p. 101]. Chernov developed a probability prediction model, which he presented in his 1987 book [Chernov, 1987]. Looking at SI as a sense-oriented communicative activity severely constrained by external factors [Chernov, 1992], he focuses on the transfer of the message from the source into target language via probability prediction and inferencing based on implicatures derived from presuppositions or preexisting (background) knowledge. Another important factor that makes probability forecasting and inferencing possible is information redundancy. A simultaneous interpreter is supposed to reconsider information density and the sentence functional perspective (theme and rheme in the terminology accepted in the Russian communicative paradigm), resorting to compression in rendering thematic or other textually redundant information.

One of the best-known SI models in European countries is the interpretative model designed by Seleskovitch and Lederer mentioned above, which is also known as théorie du sens (sense theory). The model represents interpreting as a three-phase process: 1) auditory perception in the source language; 2) retention of the mental representation of the message; 3) production of a new utterance in the target language [Seleskovitch, 1998, p. 8]. Describing this process, Lederer refers to other terms that are extensively used with regards to SI: 1) comprehension of the message in the source language; 2) sense deverbalisation and mental representation of sense units; 3) sense reverbalisation in the target language [Lederer, 2003, pp. 12, 18, 35-36]. Some researchers single out only two phases of the translation/interpreting process. For example, Lagarde and Gile outline its two phases: 1) comprehension of the text in the source language; 2) its reformulation in the target language [Lagarde, Gile, 2011]. These two phases are presented in Gile’s sequential model of translation: the meaning hypothesis based on comprehension passes the plausibility test and moves on to the second stage: reformulation [Gile, 2009, pp. 101-110]. Nevertheless, while describing the interpreter’s mental resources needed for SI, Gile looks at it through the lenses of psycholinguistics and cognition, singling out three or even four steps. Offering four process steps as its constituency, he called this representation the efforts model : (1) a listening and analysis component, (2) a speech production component, and (3) a short-term memory component, which interact through (4) a coordination effort [Gile, 2009, pp. 157-190]. These steps make it possible for the interpreter to produce a text in the target language adequate to the text in the source language.

The two currently best-known SI models in Russia are the models by Chernov, and by

Seleskovich and Lederer described above. Chernov believed that his model of probabilistic forecasting [Chernov, 2004, p. XXV] was the bridge that connects the two above-mentioned paradigms of interpreting process studies singled out by Moser. Anyway, there is no impenetrable wall between them, as those who analyse brain functions needed for SI are also interested in applied research and the study of information processing via SI cognitive mechanisms and discursive strategies, and vice versa. Currently the interdisciplinary approach is gaining momentum and it makes it possible to explore both the outcomes and the process of SI per se.

Another important issue that needs to be covered is an overview of research studies that describe approaches to translation/interpreting and, specifically, to SI competence. In this regard, it seems pertinent to highlight the landmark research studies in this area (though Zabotkina et al. have already conducted a detailed survey done in a linguodidactic paradigm [Zabotkina, Korovkina, Sudakova, 2019]). The term communicative competence was introduced into linguistics, psycholinguistics and translation studies by Zimnaya [1978]. Later Komissarov [1997] and Latyshev [2001] attempted to build a generalised competence-based translation model, using their own terms and notions, which only later were made compatible with the mainstream process. Noteworthy among leading European researchers are Nord [2005], whose functional perspective is crucial for interpreting, as well as Kiraly [2013], or Göpferich [2009].

Other researchers, including Setton and Gile, were specifically interested in the professional competences of simultaneous interpreters. Setton devised an all-round interpreting expertise model as the integration of four competencies – language, knowledge, skills, and professionalism, which included both declarative and procedural knowledge [Setton, Dawrant, 2016, p. 42]. The procedural component of knowledge highlighted by Setton has always attracted the attention of researchers interested in better understanding of interpreter’s mental processes manifest in his/her speech activities aimed at solving pragmatic tasks and bringing about the required interpreting outcomes (see Gile’s gravitational model fine-tuned to the SI mode [Gile, 2009, p. 234], or Ricardi’s views on SI in terms of procedural competence [Riccardi, 2005]). Studies of the interaction between declarative and procedural knowledge have always been a hallmark of the Soviet methodology and research, and now it is an area of interest of cognitive sciences.

The overview presented above proves the interest towards the SI cognitive processes, which may be explained by the desire to better understand them in order to adjust the cognitive and discursive strategies used by simultaneous interpreter to the pragmatic goals of a SI communicative situation. In this regard, the goal of the paper is to show the communicative and discursive specifics in realizing the SI cognitive strategies of inferencing and probabilistic forecasting and the communicative strategy of compression in the communicative practice of a simultaneous interpreter. The objectives of the paper are to:

– present a competence-based SI model devised in the course of SI practice, training and research;

– make an analysis of the key SI cognitive mechanisms or features and discursive strategies such as inferencing, probabilistic forecasting and compression, as well as of their interaction with the simultaneous interpreter’s competences and abilities, and to show that these abilities are a mirror reflection of SI cognitive features and discursive strategies;

– highlight the dependence of inferencing, probabilistic forecasting and compression on the knowledge of presuppositions which makes it possible to realize the above-mentioned cognitive strategies in SI production.

The hypothesis of the research study boils down to the following assumption: the simultaneous interpreter competence model presented in the article shows that a professional level of interpreting requires a closely-knit interaction of the three blocks of competences that will be described below in the relevant subsections. The third procedural competence, though broader in its structure, comprises the abilities of inferencing, probabilistic forecasting and compression. They are activated in the interpreter’s discursive practice in a SI communicative situation with the help of the knowledge of linguistic and extralinguistic information, related to the language and conceptual worldviews of the source and target languages, which in its essence can be reduced to the knowledge of presuppositions. Presuppositional knowledge is an enabling factor for the first two competences as well. Presuppositions are manifested in the text through the text language structures (including word combinability), its cohesion and coherence, as well as through extralinguistic information, and their acquisition is facilitated to a greater extent by the study of the functional parameters of LSP texts (LSP standing for language for special purposes) that belong to the specific domains of knowledge.

Material and methods

The material subject to the theoretic analysis in the paper is the SI process in training and in real SI communicative situations, as well as the SI outcomes, which stands for the comparison of the LSP texts in the source and target languages. Text in simultaneous interpreting are understood as both the process of interpreter’s discursive activity (speech) and its outcomes. LSP texts taken for the analysis in the paper mainly belong to political, economic and legal discourse, and they are analyzed in the paper as SI outcomes. The key function of LSP-texts is denotational (referential) with a certain influence of an expressive one. Interpreting practice shows that the text function affecting the text discursive features has a great influence on the translation method and facilitates inferencing, probabilistic forecasting and compression. LSP texts are usually full of technical terms belonging to specific domains of knowledge and have a high level of cohesion and coherence expressed by linguo-specific language means. Moreover, the discursive text analysis for interpreting encompasses both linguistic factors (the linguistic means of cohesion, its genre and leading function mentioned above) and extralinguistic factors such as the text’s recipients, cultural context, deixis of the SI communicative situation.

The examples presented in the paper mainly show interpreting from a foreign language (English, Spanish, French) into a mother tongue (Russian), as is accepted in international organizations, though retour interpreting (from Russian into English) is also subject to analysis. Though discursive strategies expostulated below may be regarded as universal tools and can be applied to any language, there are some differences in their communicative realization because of linguistic and pragmatic factors such as intercultural and interlanguage asymmetries between SL and TL, which may refer both to different languages and the direction of interpreting – from a foreign language into a mother tongue and vice versa (retour).

Results and discussion

Cognitive and communicative perspective in the choice of SI discursive strategies

The SI objectives, that is, making a success of an act of intercultural communication through mediation, can be attained only if the simultaneous interpreter has the required skills and abilities. These abilities help to resort to discursive strategies enabling him/her to convey the message from the source into the target language. The types of the discursive strategies and their language realization depend on the pragmatic features of the SI communicative situation and the cognitive nature of simultaneous interpreting per se.

The discursive text analysis for the SI purposes means that a simultaneous interpreter has to know the deixis of the SI communicative situation – its time, place, speakers and SI recipients, as well as the topic of the discussion. He/she has also to be well-versed in the specific domain of knowledge to be discussed during a SI event and the linguistic means and discursive features of LSP text, as well as to be capable of using general (encyclopaedic) knowledge about the world and cultures. All this knowledge, both linguistic and extralinguistic, is activated through the procedural skills of information processing – inferencing, probabilistic forecasting and compression that enable the interpreter to interpret and render the invariant sense, switching over from the source into target languages.

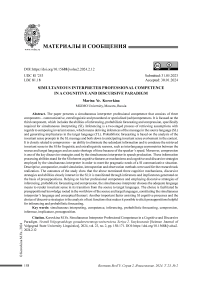

Below, in Figure 1, follows a graphic representation of a competence-based model of simultaneous interpreting that demonstrates the SI feasibility. The SI professional competence model is based on the translation competence model first presented in [Korovkina, 2017].

The competences are incorporated into the interpreter’s ‘language personality’, which has several ideational layers. The term language personality (homo loquens) was introduced into the Russian linguistics by Karaulov [2004]. He singled out three levels of language personality related to language and cognition: verbal or semantic (lexicon, grammar and connectors), conceptual (ideas and notions), and pragmaticon or motivations (mindset, behavioral dynamics). The first two levels are called by Karaulov language and conceptual thesauri. The first relates to the specifics of the worldview expressed in the language structures, and the second to the differences in the worldview’s conceptualization and categorization reflected in scripts, frames, etc. These two levels of the language personality are closely tied to the SI competence components.

The first competence component of the model is the communicative competence , which includes language/linguistic and pragmatic constituents. The pragmatic constituent comprises the following subcompetences: deictic defined by the parameters of the communicative situation; discursive related to the text features and functions; and sociocultural , which amounts to realizing cross-cultural competence in speech. The pragmatic constituent is closely related to the linguistic one, as it is manifested in text through language structures (that is why it is included in the communicative competence), as well as to

Fig. 1. SI professional competence model

extralinguistic information that determines the simultaneous interpreter’s choice of discursive strategy. The communicative competence reflects the level of the development of the interpreter’s language world views or thesasuri (of source and target languages).

The second component represents the extralinguistic competence , which includes knowledge of the world in general (or encyclopedic knowledge), of the cultures of source and target languages, and of specific domains or subject areas referred to in SI. It also represents the interpreter’s knowledge of the conceptual worldview and of terms and notions.

The third component relates to a specialized or procedural competence , which comprises the following three procedural abilities and skills:

-

1) simultaneous activation of two speech channels controlled by self-monitoring, which means listening and speaking at the same time;

-

2) information processing abilities – inferencing, probabilistic forecasting and compression – SI inherent cognitive features or mechanisms introduced above; they stand for interpreter’s specific procedural information processing cognitive abilities, as well as for his/her discursive strategies chosen for a specific act of communication interpreted simultaneously. The SI discursive strategies result in the SI outcomes that present invariant sense interpretation often done with the help of specific translation shifts or transformations in case of language asymmetries or through a stereotypic speech patterns;

-

3) transfer or technological subcompetence , the ability to switch over from the source to target language resorting to the above-mentioned information processing abilities and discursive strategies.

The first two components represent the declarative knowledge, while the third one includes the procedural knowledge or abilities, activating the first two competences in the process of interpreting in their reception and production phase. In the phase of reception the simultaneous interpreter listens to SL message and grasps its invariant sense, in the production phase he/she reformulates or reverbalizes it. The translation decision may take just a fraction of a second, nevertheless it is singled out as a stage in the SI process and it connects the reception and production phases.

Though all the competences described in the model are manifested in SI in a very specific way, the success in SI to a greater extent depends on the procedural and analytic abilities of information processing through inferencing, probabilistic forecasting/anticipation and compression, which also represent the SI key cognitive mechanisms and interpreter’s discursive strategies. There are two types of discursive strategies – cognitive and communicative ones – the simultaneous interpreter resorts to. The first type stands for those preconditioned by the cognitive nature of interpreting, or speech reception and production activity that involves shifts between the source and target languages. They include inferencing and probabilistic forecasting, and, as has already been mentioned, they are inherent cognitive features of simultaneous interpreting. The SI discursive strategies of the second type can be called communicative, as they are to a greater extent manifested in the language expression and depend on the linguistic and pragmatic features of the SI communicative situation. Only the key communicative strategy, which is sense compression, is explored in the paper. Both the cognitive and communicative strategies are used by the simultaneous interpreter in order to process information related to the invariant sense contained in the source language text and to convey it in the target language.

In order to be able to interpret the invariant sense the simultaneous interpreter has to grasp the sense of the message in the source language through inferences – assumptions made in the course of understanding the speaker. As stated above, the second stage of the interpreting process is making a translation decision, which takes a fraction of a second in SI, while in translation it may take quite an extended period of time. The third stage of the interpreting process stands for reformulation or reverbalization of the SL message in TL. While reformulating the message in the target language the interpreter generates implicatures trying to realign the presuppositional knowledge of the communicants. Through interactive realignment (the term introduced in translation studies by Zabotkina [2020, pp. 77-78]) an interpreter has to take into account the gaps in linguistic and extralinguistic knowledge or intercultural and interlanguage asymmetries between source and target languages and make respective adjustments, which may also be regarded as the realignment of the mental space or language world views of intercultural communicants. In our view, the simultaneous interpreter makes mental realignment through the choice of discursive strategies based on the adjustments in prepositional knowledge of the communicants representing different linguistic communities.

The cognitive nature of presuppositions is similar to that of inferences/implicatures, which has made it possible to break up both presuppositions and inferences/implicatures into two groups: language-based/linguistic and cognitive /extralinguistic.

Language-based presuppositions relate, on the one hand, to the linguistic structures of the text in the source and target languages that reflect language asymmetries caused by the discrepancies in the worldviews between both languages, including word combinability and the discursive specifics of the text in the source and target languages. This stands for the text cohesion and coherence, which is expressed in the way the information is presented: theme and rheme (sentence functional perspective), repetitions at both the lexical and the semantic levels (which can create an adequate level of information redundancy in the text), use of logical connectors and other means of text coherence. Languagebased presuppositions also refer to denotates or referents described in the text, which makes them correlate with the extralinguistic reality and extralinguistic presuppositions. Below follow the examples of language-based presuppositions related to the key language asymmetries: grammar metaphor or animalism of the European languages: the month has seen a bankruptcy – в этом месяце произошло банкротство..., la economia real no despega – в реальной экономике продолжается кризис, la crise financiиre lui a fait perdre ses illusions – после финансового кризиса он расстался со всеми своими иллюзиями; metaphors referring to specific denotates in different languages – the imagery of the language: to go down the drain, foul play, les entraves, le miroir aux alouettes, redil atlántico, bacanazo – the translation of these expressions in SI (as well as in other translation modes) depends on the context. There are many examples of other types of language asymmetries, for example, language-specific word collocations – strong man, deep love, heavy rain, in Russian the invariant sense is covered by one word: сильный человек, сильная любовь, сильный дождь; implicit language models, when the situation is described with one word or with lesser number of worlds in one language compared to the other, for example, the English word compliance needs explicitation in the translation into Russian.

Extralinguistic presuppositions arise from extralinguistic information, narrow text and broad pragmatic contexts that include both general encyclopedic knowledge, knowledge of culture of both languages and knowledge in a specific domain that would be covered by an SI event (there may be several related subject areas) and its specific communicative situation (topic, speakers, listeners, deixis). An example below deals with fishing, and its understanding and interpreting is possible only on the basis of extralinguistic knowledge. If an interpreter does not immediately remember the exact translation of all the words relating to fishing, he/she will be able to render an invariant sense of this sentence making inferences and generating implicatures on the basis of the presuppositional knowledge about fishing – lake – trout (fish) – chum:

-

(1) Adam Jonas, head of global auto research at Morgan Stanley, a bank, explains it with a fishing analogy : “The IRA (Inflation Reduction Act) stocks the lake full of trout . And now the states are there trying to attract the trout with chum .” – Адам Джонас, глава отдела исследований глобального автомобильного рынка банка «Морган Стэнли», объясняет ситуацию, прибегая к аналогии с рыбной ловлей : «Данный закон (Акт о сокращении инфляции) привлекает в озеро много форели . А теперь штаты пытаются ловить форель на наживку .

The cognitive strategy of inferencing is closely related in SI to probabilistic forecasting that stands for the identification of the key invariant sense prompts that make it possible to predict how the sense will unfold in the text. Sometimes these two strategies may overlap, if the invariant sense is anticipated at the level of a small translation unit, such as a word or an utterance. If it is anticipated at the level of several utterances or even the whole text, which happens only in SI, it is probabilistic forecasting per se. The realization of this cognitive strategy in SI is facilitated by an analysis of textual density of information and its redundancy. If redundancy is detected, the interpreter resorts to compression described below, leaving out textually redundant information. The activation of these strategies – both cognitive and communicative – is assisted by the knowledge of presuppositions of both types. The languagebased presuppositions help to identify key language means used to convey invariant sense, while the extralinguistic ones serve as the basis for the general understanding of the text logic and sense unfolding. If the prediction or sense anticipation is not confirmed while interpreting, an interpreter makes relevant adjustments, as in the example following below:

-

(2) La ley 7 de 2013 para la esterilización femenina gratuita requiera a las mujeres tener mínimo 23 años, dos hijos y una recomendación médica, mientras que sólo exige a los hombres tener 18 años.

Wrong: В соответствии с законом о бесплатной женской стерилизации , женщине должно быть не менее 23 лет.

Correct: В соответствии с Законом № 7 от 2013 года, для осуществления бесплатной стерилизации женщине должно быть не менее 23 лет, она должна иметь двух детей и получить медицинскую рекомендацию, в то время как для мужчин требуется лишь достижение 18-летнего возраста.

The interpreter has decided that the law refers only to women, which shows that she lacked the required prepositional knowledge about the law content and made wrong inferences (or mistakes in inferencing). In the course of text evolvement, when men were mentioned, she realized her mistake and corrected it.

The interpreting practice shows that the third SI cognitive feature and discursive strategy used by the simultaneous interpreter is compression. It can be regarded as a communicative strategy, as to a great extent it depends on the communicative situation and its pragmatic features. The interpreter has to resort to it both due to extralinguistic reasons – the speaker’s speed, and the linguistic ones – language asymmetries in implicit information, quite often accompanied by various types of transformational shifts (explicitation or implication, generalization, specification, metonymy). In all translation modes the translator/interpreter deverbalizes and reverbalizes the invariant sense choosing between the clichés and stereotypes and sense interpretation (see Gile’s gravitational model and the need for a high language availability in SI) [Gile, 2009, p. 234]. Often different features of the denotational situation in the source language become explicit or implicit in the target language. But in SI the interpreter must make a decision on specific language means without any delays because of the speaker’s speed. If it is above 100– 120 words per minute, the interpreter has to catch up with the speaker, so he or she has to eliminate redundant information based on inferencing and probabilistic forecasting, irrespective of the direction of interpreting. Moreover, the need to resort to compression becomes even more acute in case of the retour interpreting in the language pairs of English and Russian because of the structural and semantic interlanguage asymmetries, as English is more implicit compared to Russian. If interpreting is direct, for example, from English into Russian, even if the speed is under 100–120 words per minute, the interpreter must resort to sense compression, leaving out redundant bits, for the same reason of greater implicitness of the source language. Moreover, in both directions of interpreting the interpreter may also have to make some explicitation of the key information explaining some points in order to make realignment between the worldviews of the sender of the message in the source language and its recipient in the target language. Below follows an example of compression used in SI retour from Russian into English:

-

(3) Пандемия коронавируса стала дополнительным фактором фрагментации и тревожности в международных отношениях. Вместе с тем глобальный кризис вновь со всей очевидностью показал необходимость сообща вырабатывать системные ответы на общие вызовы, противодействовать реальным, а не надуманным угрозам. – The pandemic has become an additional factor of anxiety in international relations. The global crisis has again shown the need to jointly work out (omission) responses to common real challenges .

The analysis of the example shows that an interpreter resorted to structural-semantic compression, as is often the case in retour interpreting from Russian into English.

The simultaneous interpreter is capable of resorting to all the described discursive strategies and produce SI outcomes adequate to the communicative situation, with the focus on the invariant sense and text’s cohesion, only if he/she has acquired a set of professional competences described above.

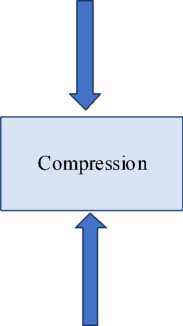

The Figure 2 below shows the interaction between the SI cognitive features, the simultaneous interpreter’s discursive strategies and his/her professional competences.

As it has been stated above, the use of discursive strategies depends on the mastery of the competences, which it its turn is facilitated by the step-by-step acquisition of presuppositional knowledge on the basis of LSP texts belonging to the specific domains, which is a never-ending process for the simultaneous interpreter. The specific features of LSP texts described above require a high degree of equivalence and adequacy in interpreting: fidelity for the source texts, coherence for the target texts [Schaeffner, 2000] and loyalty for both. Loyalty in interpreting

SI cognitive mechanisms/discursive strategies

Probabilistic forecasting

Inferencing т

|

Specialized competence |

|

|

Communicative competence |

Extralinguistic competence |

|

Interpreter’s language thesaurus |

Interpreter’s conceptual thesaurus |

|

Language worldview |

Conceptual worldview |

Fig. 2. The interaction between the SI cognitive mechanisms and discursive strategies, SI professional competences and the language worldview

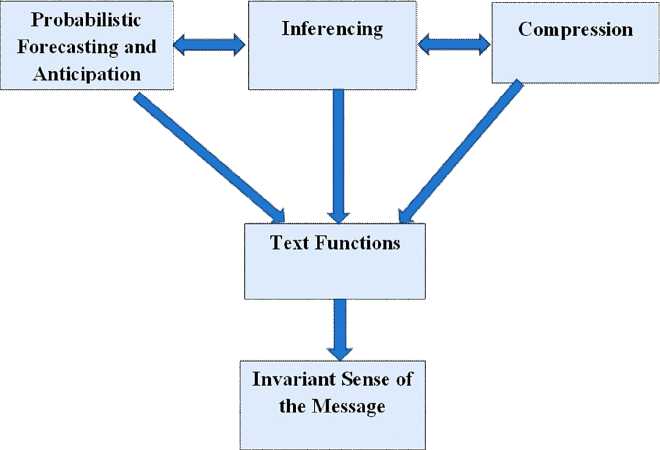

is understood as rendering communicative intentions of the sender of SL text and living up to the expectations of the TL text recipients [Nord, 2005]. In SI there is a certain degree of freedom attributable to the need of resorting to probabilistic forecasting and compression due to extralinguistic factors. The focus in SI is on the invariant sense and text’s cohesion, which has to be reproduced in SI by linguospecific means of the target language. Figure 3 below shows the interaction between the discursive strategies chosen by the simultaneous interpreter and the text function in rendering the invariant sense of the SL message in the target language.

The example below illustrates how the interaction of linguistic and extralinguistic prepositional knowledge (shown in bald type) confined to the texts of international and economic political discourse, which have specific text functions mentioned above, enables an interpreter to grasp the invariant sense in the source language and to render it in the target one:

-

(4) We would not have the UN Law of the Sea or the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and a great many other outcomes – but for the political will of SIDS . We are a quarter of this body’s membership . – Мы бы не смогли принять Конвенцию ООН по морскому праву, Рамочную конвенцию ООН об изменении климата и многие другие международные договоры / инструменты (the second more exact interpretation option: или добиться других важных результатов) , если бы не по-

- литическая воля малых островных государств (МОРАГ). Ведь мы составляем четверть членов ООН (нашей организации).

Conclusions

The knowledge of the language as a set of rules and of the extralinguistic situation serves as anchors for better understanding of the invariant sense unfolding in the SL message in the process of simultaneous interpreting. The text reproduced by simultaneous interpreter is the outcome of his/her discursive activity based on cognitive information processing done with the help of the discursive – cognitive and communicative – strategies described in the article. Their interaction in the SI process and interrelation with three components of interpreter’s professional competence is a holistic process that depends on the level of development of ‘an interpreter’s language personality’ based on the interpreter’s language and conceptual thesauri rooted in the language and conceptual word view. Both thesauri represent presuppositional knowledge that facilitates the communicative realization of SI cognitive mechanisms in the format of discursive strategies. Their selection and communicative realization depends in its turn on the mastery of the communicative, extralinguistic and specialized or procedural competences described in the SI professional competence model presented in the paper.

Fig. 3. The SI discursive strategies and text function

The communicative competence stands for the mastery of the linguistic knowledge and speech skills given the discursive, cultural and structural specifics of the source and target languages. This component is supported by the extralinguistic competence, which, as has been highlighted in the article, includes the knowledge of cultures, of specific domains, and general encyclopedic knowledge. The third specialized or procedural competence consists of cognitive information processing abilities – inferencing, probabilistic forecasting and compression – that makes the SI feasible. Though comprising a broader set of skills and abilities, the third component is a mirror reflection of the SI cognitive mechanisms.

In the process of a SI communicative act an interpreter uses his/her a whole set of competences to implement the cognitive strategy of inferencing. This means inferring the invariant sense of the text/message in the source language and implying it in the target language. Inferencing is facilitated by the cognitive strategy of probabilistic forecasting, as the interpreter makes a forecast of sense unfolding in the SL text. If the anticipation is not correct, the interpreter makes respective adjustments in the TL text. The cognitive strategies of inferencing and probabilistic forecasting reflect the SI inherent cognitive features that make SI possible. Their language realization is facilitated by compression, a third discursive strategy used by the interpreter for linguistic reasons – differences in the implicit language models between SL and TL, as well as the extralinguistic ones – acute shortage of time. As compression depends on the specific features of a SI communicative situation, it may be called a communicative strategy. It also makes it possible to leave out redundant bits of information and presupposes a certain freedom of interpreting constrained by an acute shortage of time. Moreover, the specific language means are chosen with due regard for the differences in the worldview between the source and target languages and for the need to make interactive mental alignment of the discrepancies in the worldviews of communicants belonging to different linguistic communities.

The employment of these three discursive strategies leads to successful sense interpretation in a SI communicative act on the basis of the presuppositional knowledge of both linguistic and extralinguistic nature, given text functions and its discursive features, enabling a simultaneous interpreter to make a choice of linguistic means adequate to the SI communicative situation with regards to the need in interactive alignment and rendering of the invariant sense of the message from the source to target language.

Список литературы Simultaneous Interpreter Professional Competence in a Cognitive and Discursive Paradigm

- Chernov G.V., 1987. Osnovy sinkhronnogo perevoda [The Fundamentals of Simultaneous Interpreting]. Moscow, Vyssh. shk. 256 p.

- Chernov G.V., 1992. Conference Interpreting in the USSR: History, Theory, New Frontiers. Meta 37, no. 1, pp. 149-162. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/002227ar

- Chernov G.V., 2004. Inference and Anticipation in Simultaneous Interpreting. A Probability-Prediction Model. Amsterdam, Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company. 266 p.

- Déjean Le Féal, K., 1991. “La liberté en traduction.” Meta 36, no. 2-3, pp. 448-455. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/003449ar.

- Gerver D., 1975. A Psychological Approach to Simultaneous Interpretation. Meta 20, pp. 119-128.

- Gile D., 2009. Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training. Amsterdam, Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company. 283 p.

- Göpferich S., 2009. Towards a Model of Translation Competence and Its Acquisition: The Longitudinal Study Trans Comp. Göpferich S. et al., eds. Behind the Mind: Methods, Models and Results in Translation Process Research. Copenhagen, Samfundslitteratur, pp. 12-38.

- Kalina S., 1992. Discourse Processing and Interpreting Strategies – An Approach to the Teaching of Interpreting. Dolerup C., Loddegaard A., eds. Teaching Translation and Interpreting: Training, Talent and Experience. Papers from the First Language International Conference. Elsinore, Denmark, 31 May – 2 June 1991. Amsterdam, Philadelphia, John Benjamins, pp. 251-259.

- Karaulov Y., 2004. Russkiy yazyk i yazykovaya lichnost [The Russian Language and Language Personality]. Moscow, URSS Publ. 264 p.

- Kiraly D., 2013. Towards a View of Translator Competence as an Emergent Phenomenon: Thinking Outside the Box(es) in Translator Education. Kiraly D. et al., eds. New Prospects and Perspectives for Educating Language Mediators. Tübingen, Gunter Narr, pp. 197-224.

- Komissarov V., 1997. Teoreticheskie osnovy metodiki obucheniya perevodu [Theoretic Fundamentals of Translation Teaching Methods]. Moscow, Rema Publ. 110 p.

- Korovkina M., 2017. Teoreticheskie aspekty smyslovogo modelirovaniya spetsialnogo perevoda s rodnogo yazyka na inostrannyy (na materiale publitsisticheskikh tekstov ehkonomicheskoy tematiki): dis. ... kand. filol. nauk [Theoretic Aspects of Sense Modelling in LSP-Translation from Mother Tongue into Foreign Language (on the Basis of Journalistic Texts of Economic Discourse). Cand. philol. sci. diss.]. Moscow. 241 p.

- Korovkina M., Semenov A., 2022. Inferirovanie i funktsionalnyy podkhod k tekstu: na material sinkhronnogo perevoda [Inferencing and Functional Approach to Text: Based on Simultaneous Interpreting]. Vestnik Rossiyskogo universiteta druzhby narodov. Seriya: Teoriya yazyka. Semiotika. Semantika [Bulletin of Russian People’s Friendship University. Series: Language Theory. Semiotics. Semantics], vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 337-352.

- Lagarde L., Gile D., 2011. Le traducteur professionnel face aux textes techniques et à la recherché documentaire. Meta 56, no. 1, pp. 188-199. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1003517ar

- Lambert S., 1988. Information Processing Among Conference Interpreters: A Test of the Depthof-Processing Hypothesis. Meta 33, no. 3, pp. 377-387. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/003380ar

- Latyshev L., 2001. Tekhnologiya perevoda [Translation Technology]. Moscow, NVITesaurus Publ. 278 p.

- Lederer M., 1981. La traduction simultanée: experience et théorie. Paris, Minard Lettres Modernes. 454 p.

- Lederer M., 2003. Translation. The Interpretative Model. Manchester, St. Jerome Publishing. 239 p.

- Massaro D., 1975. Language and Information Processing. Massaro D., ed. Understanding Language. New York, Academic Press, pp. 3-28.

- Moser B., 1978. Simultaneous Interpretation: A Hypothetical Model and Its Practical Application. Gerver D., Sinailo H.W., eds. Language Interpretation and Communication. New York, London, Plenum Press, pp. 353-368.

- Moser-Mercer B., 1994. Paradigms Gained or the Art of Productive Disagreement. Lambert S., Moser- Mercer B., eds. Bridging the Gap: Empirical Research in Simultaneous Interpreting. Amsterdam, Philadelphia, John Benjamins, pp. 17-23.

- Nord Ch., 2005. Text Analysis in Translation: Theory, Methodology and Didactic Application of a Model for Translation-Oriented Text Analysis. Amsterdam, New York, Rodopi. 274 p.

- Pöchhacher F., 1995. Simultaneous Interpreting: A Functionalist Perspective. Hermes, Journal of Linguistics, no. 14, pp. 31-53.

- Riccardi A., 2005. On the Evolution of Interpreting Strategies in Simultaneous Interpreting. Meta 50, no. 2, pp. 753-767. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/011016ar

- Schaeffner Ch., 2000. Running Before Walking? Designing a Translation Programme at Undergraduate Level. Schaffner C., Adab B., eds. Developing Translation Competence. Amsterdam, Philadelphia, John Benjamins, pp. 143-155.

- Seleskovitch D., 1998. Interpreting for International Conferences. Washington, Pen and Booth. 138 p.

- Setton R., 1999. Simultaneous Interpretation: A Cognitive-Pragmatic Analysis. Amsterdam, Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company. 397 p.

- Setton R., Dawrant A., 2016. Conference Interpreting: A Trainer’s Guide. Amsterdam, Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company. 650 p.

- Shiriayev A., 1979. Sinkhronnyi perevod: Deyatelnost sinkhronnogo perevodchika i metodika prepodavaniya sinkhronnogo perevoda [Simultaneous Interpretation. The Activity of a Simultaneous Interpreter and Methods of Teaching Simultaneous Interpretation]. Moscow, Publishing House of the Defense Ministry. 183 p.

- Shlesinger M., 2000. Interpreting as a Cognitive Process: How Can We Know What Really Happens? Tirkkonen-Condit S., Jaaskelainen R., eds. Tapping and Mapping the Processes of Translation and Interpreting: Outlooks on Empirical Research. Amsterdam, Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 3-16.

- Zabotkina V., 2020. Kognitivnye mekhanizmy mezhkulturnogo dialoga [Cognitive Mechanisms of Intercultural Dialogue]. Kognitivnye issledovaniya yazyka [Cognitive Studies of Language], no. 2 (41), pp. 76-80.

- Zabotkina V., Korovkina M., Sudakova O., 2019. Competence-Based Approach to a Module Design for the Master Degree Programme in Translation: Challenge of Tuning Russia Tempus Project. Tuning Journal for Higher Education. Vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 67-92. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18543/tjhe-7(1)-2019pp67-92

- Zimnaya I., 1978. Psikhologicheskie aspekty obucheniya govoreniyu na inostrannom yazyke [Psychological Aspects of Teaching Speaking a Foreign Language]. Moscow, Prosveshcheniye Publ. 160 p.