Teaching ESP online: a guide to innovation in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis

Автор: Vera Ošmjanski

Журнал: International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education @ijcrsee

Рубрика: Original research

Статья в выпуске: 3 vol.10, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The paper studies the student experiences related to online teaching of English for Specific Purposes (ESP) in order to determine which computer-mediated learning practices were perceived as purposeful and should be incorporated in traditional in-person teaching. The sample comprised of 60 students from two faculties of the University of Belgrade, Serbia. Descriptive statistics were obtained. The gathered data were subjected to qualitative and quantitative data analysis. The results indicate that the positive experiences are related primarily to synchronous conferencing in the form of real-time written communication as an integral part of the classes offered via videoconferencing. The use of video content and availability of various learning materials uploaded to the learning platforms proved to be helpful. Loss of concentration, technical difficulties and a lack of in-person communication were perceived as obstacles to effective learning. The most salient conclusion of the study refers to the necessity of incorporating real-time comment writing in the traditional classroom. The results also urge the need for addressing the issues of large classes and inadequate auditoriums in the traditional mode of teaching. The conclusions provide the guidelines for the improvement of in-person teaching of ESP based on specific computer-mediated learning practices that were found facilitative of the development of the students’ language competencies.

Online teaching, english for specific purposes, computer-mediated learning, synchronous conferencing, synchronous online teaching, teaching methods

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170198680

IDR: 170198680 | УДК: 378.147::811.111 | DOI: 10.23947/2334-8496-2022-10-3-149-154

Текст научной статьи Teaching ESP online: a guide to innovation in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the consequent declaration of a state of emergency in the Republic of Serbia in March 2020 shifted academic activities online. By the beginning of April 2022, the modes of both asynchronous and synchronous online teaching were introduced.

From the very beginning of the pandemic in March 2020 to the end of the spring term in June 2020, the University of Belgrade offered asynchronous online teaching using platforms such as Moodle, Zoom, and Google classroom. Online teaching has long since been introduced to higher education ( Harasim et al., 1995 ; Hiltz 1986 ), yet the Covid-19 pandemic imposed an abrupt shift. The transition was to be prepared at very short notice, so it “is an important consideration when evaluating how the various challenges were met” ( Forrester, 2020 ).

The students were provided with an online access to the selected learning materials, PPT presentations, additional literature, homework and tests. The main channel of student-teacher communication was e-mail. Homework was regularly assigned and submitted via Google classroom. Upon the assessment, the students were given a timely feedback. In the newly imposed circumstances, homework was a substitute for the mid-term tests, while the final exam was conducted exclusively as a written exam.

In difference to the spring term of 2020/21 being completely online, at the beginning of academic 2021/2022, there was a transition to synchronous online teaching. Depending on the epidemiological reports, online, combined, hybrid and traditional (face-to-face) modes of teaching alternated. The lectures were held in real time via online platforms, while the seminar classes were held in small groups at the faculty. During this period, it was possible to conduct the written mid-term assessments as well as the final oral exams in the format used prior to the pandemic.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, teaching English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and English for

© 2022 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license .

Specific Purposes (ESP) was to pursue yet another goal –adapting the entire teaching process to online mode as a stopgap solution. Compared to their counterparts, language teachers faced a considerable challenge as one of the primary goals of foreign language teaching is the achievement of communicative language competence. According to the Common European Framework of Reference for Language Learning, Teaching and Evaluation, communicativelanguage competenceincludeslinguistic, sociolinguistic and pragmatic competence. According to Byram (1997) , language teaching has yet another goal - the acquisition of intercultural competence that facilitates understanding and communication in culturally diverse environments. The specificity of teaching ESP is that it “involves teaching the literacy skills which are appropriate to the purposes and understandings of particular communities” ( Hyland, 2002 ). Its goals are partly socio-historical, legal and intercultural, and partly linguistic, i.e. lexical, grammatical, and logical-discursive (Dion 2007, pp. 183- 184, as cited in Vujović 2010, p. 208 ). Effective work on the attainment of these goals is additionally challenged in online teaching, prompting innovation and creative approaches.

Apart from the disciplinary specificity, teaching ESP does not neglect developing the productive skills – speaking and writing, as well as the receptive skills – reading and listening. In a digital learning environment, the development of speaking is facilitated merely via online speaking activities including participation in online class discussions. On the other hand, activities for the development of receptive skills, e.g. listening, might considerably diversify taking the advantage of the easily accessible Internet video segments from interviews, lectures, films, and educational video clips. In case of writing, computer-mediated learning provide the students with another form of written interaction with the teacher and classmates in real time through the comment section on the platform screen. Namely, the students are encouraged to send their written comments, which requires fast adjustment to tracking and comprehending multiple simultaneous threads. Also, there is the possibility of submitting homework assignments in writing via the platform. Synchronous online teaching also allows for student presentations to be held, individually and in groups. On the other hand, the digital environment is unfavourable for conducting activities such as work in pairs or work in small groups in real time.

Materials and Methods

The research was conducted in May 2022 and included 60 respondents, first-year students of the Faculty of Philosophy, and Faculty of Technology and Metallurgy of the University of Belgrade. The research was descriptive. The obtained data were subjected to qualitative and quantitative data analysis. A questionnaire was constructed as a measuring instrument consisting of 36 items, 24 closed-ended and 12 open-ended.

The research questions were grouped into three parts. The first part referred to the technical aspects of online teaching. The second part dealt with the psychological and pedagogical aspects, i.e. motivation, concentration, the ability to deal with the learning material, improvement of productive and receptive skills, and interaction with the teacher and classmates. The third part was related to determining the specific advantages and disadvantages of online ESP teaching from the students’ perspective.

Results and Discussions

Firstly, the respondents’ experiences of the technical aspects of online teaching were examined. The results indicate that as many as 76.3% of the respondents faced technical problems during synchronous online classes. In most cases the respondents mentioned the instability and quality of the Internet connection. On the other hand, the accessibility of virtual classrooms from any location was regarded as an advantage by 83.1% of the respondents. The respondents also expressed the need for lectures to be held in the morning, as they had been experiencing decreased concentration in the afternoon.

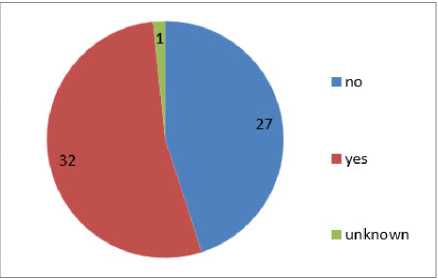

Another set of questions referred to the respondents’ perception of online ESP courses. When it comes to student motivation, the results show that 54.2% of the respondents were motivated to attend online classes (Figure 1). However, the reasons given by the poorly motivated respondents were related to the lack of concentration and interaction. These respondents mentioned other potentially disruptive factors such as the presence and activities of their household members or the challenge of performing other activities during class time. The results also indicate that 59.3% of the respondents found it difficult to maintain concentration during synchronous online classes. The decline in concentration was most often affected by the people and things from the surroundings, as well as the possibility of browsing the Internet during class time. According to the results, the majority of the respondents (55.9%) resorted to this activity during online classes.

Figure 1. Number of the respondents motivated for attending online classes

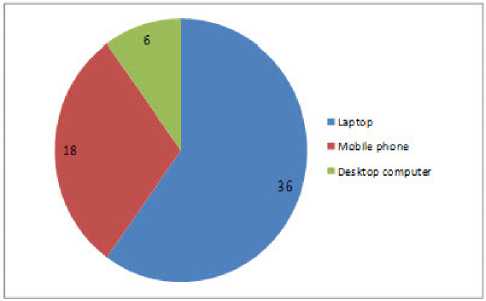

When it comes to the types of devices used during online classes, the majority of the respondents (60%) opted for a laptop, while only 6 respondents (10%) used a desktop computer. Such results might be significant for the optimization of display formats of the learning materials (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Device types used during online classes

On the other hand, the majority of the respondents (61%) stated that online teaching stimulates their motivation for active class participation. However, the reasons of the students (22) who were demotivated to participate in classes should be seriously taken into consideration. The principal objections were as follows:

“I’m less motivated to participate in online classes as there’s no face-to–face contact”;

“I can participate in completing exercises online, but I don’t have enough confidence to join realtime discussions and express my opinion. It’s very unusual to engage in class conversations without being able to see other participants”;

“expressing my opinion in an online class makes me more uncomfortable than expressing it in person”;

“the screen often freezes and the sound is not clear; overall, it’s exhausting”.

Regardless of the results that indicate that the respondents were not mainly discouraged to participate in various online class activities, the above mentioned comments clearly suggest that participation in synchronous online classes still poses a significant challenge for the students.

These answers correspond to the answers given to the question whether online teaching increased student interest in the ESP course. The majority of the respondents (52.5%) claimed that online teaching negatively affected interest in the course. The results indicate that the vast majority of the respondents still tried to attend online lectures, although a smaller percentage (15.3%) of the students stated that they joined online classes pro forma without actually following their content.

A large percentage (79.7%) of the respondents also claimed that online teaching had a positive effect on dealing with the learning materials. The difficulties that students experienced were mainly related to the lack of concentration and loss of focus.

The analysis indicates that peer communication and interaction during synchronous online classes was not satisfactory. Namely, 54.2% of the students stated that online teaching did not positively affect classroom interaction. On the other hand, the majority of the respondents (61%) claimed that peer collaboration in preparation of debates and presentations was facilitated online. Disagreeing comments emphasize the benefits of communication in person. The most common comment was:

“Communication in person is always better and more effective”.

Some comments such as “I believe communication would be much better if it were in person, because facial expressions and gesticulation often have great persuasive power” warn that the sociopragmatic aspect of language teaching might be neglected in online classes.

When asked whether they had better collaboration with the teacher online, 52.5% of the respondents answered negatively, stating that there was no difference in student-teacher collaboration compared to the traditional mode of teaching. Typical comments highlighting the positive aspects of online collaboration with the teacher were as follows:

“I feel more comfortable to ask questions online”;

“The teacher can read or hear each student’s comment and everyone is given opportunity to participate, unlike in the massively attended in-person classes”;

“I can hear the teacher better online than in spacious classrooms”.

These comments clearly suggest that in-person teaching should seriously address the issue of teaching ESP to large classes and in inadequate classrooms. This problem constantly accompanies foreign language teaching, as the solution is left to teachers themselves and it remains so ( Carbone, 1998 ; Cooper and Robinson, 2000 ).

One of the questions referred to the homework assignments which accounted for independent student work and were part of the overall grade. The students were obliged to submit their homework on schedule. This type of activity was positively assessed by a very high percentage of the respondents (91.5%). The students’ comments mostly emphasize the usefulness of such an assignment, but one comment drew attention to its misuse:

“the copies of homework are easily distributed among students; sometimes, a couple of students do their homework and share it”.

This comment suggests that homework assignments should be tailor-made for each student, which poses a great challenge for teachers teaching ESP to large classes.

The results indicate that the highest percentage of the respondents (95%) positively assessed the upload of the accompanying learning materials to the platform. This practice was not a novel one as it had been introduced long before the Covid-19 pandemic. Open-source learning platforms, such as Moodle have been used for posting PPT presentations, additional literature, and homework assignments. Uploading various learning materials has grown in importance, intensity and scope, particularly in asynchronous learning. Moreover, the use of instructor-generated video content in asynchronous online courses is found to favourably influence creating social and teaching presence, as well as student satisfaction ( Lapadat, 2002 ).

The results of this study are in line with the above findings, indicating the importance of video content in synchronous online classes, as well. The majority of respondents (81.1%) were of the opinion that the use of various video materials such as excerpts from lectures, interviews and films, as well as educational video clips was purposeful.

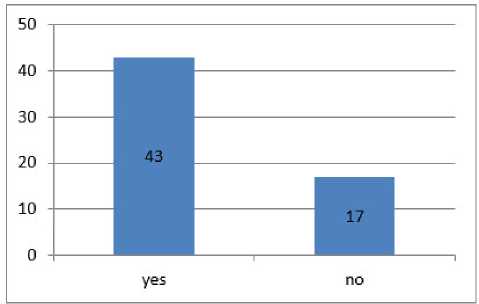

The analysis of the results determines that the possibility of synchronous conferencing (Figure 3) in the form of writing comments in real time during class was of special importance for the development of writing skills. 71.2% of the respondents confirmed this. Synchronous conferencing was an adjunct to synchronous online classes, so a way should be found to enable this kind of the participants’ interaction in face-to-face classes. Apart from learning benefits, it might considerably increase the number of students participating in class activities. It also implies greater involvement on behalf of teachers and their ability to handle both oral and written student feedback.

Figure 3. Number of the respondents who consider real time comment writing beneficial

Finally, the respondents were asked to list the specific advantages and disadvantages of online ESP, as well as newly introduced practices that should become an integral part of the future learning. As for the advantages, typical comments emphasized accessibility, saving time and the availability of learning materials on the platform. When it comes to the disadvantages, the respondents mentioned a lack of in-person communication, a lack of concentration and technical difficulties. According to the respondents, the practices that should be maintained include posting learning materials on platforms and homework assignments.

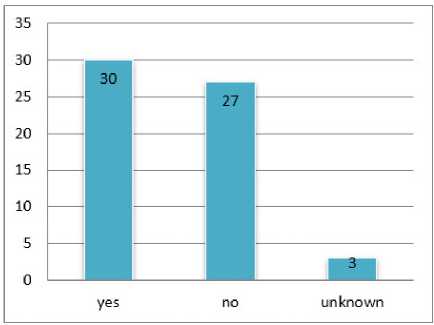

The research also examined the respondents’ perception of the effectiveness of online ESP from the perspective of the development of their language skills (speaking, listening, reading and writing). The results (Figure 4) show that there was almost an equal percentage of the students who registered the improvement (50.8%) and of those who did not (49.2%). Such results imply that online ESP teaching was not perceived as purposeless, but it definitely failed to affect the respondents’ perception of the enhancement of their language skills.

Figure 4. Perception of the effectiveness of online ESP

Conclusions

The paper has analysed the student experiences of computer-mediated learning of ESP, covering its technical, psychological and pedagogical aspects.

The most salient conclusion of the study refers to the necessity of incorporating real-time comment writing in the traditional classroom. As documented by the research, interactive online writing was perceived as beneficial. Lapadat (2002) further argues that it “provides the benefits of writing oneself into understanding, as well as a social milieu that elicits thoughtful contributions, and provides timely, contextually-appropriate feedback”. Educators are faced with the challenge of incorporating this activity into the traditional mode of teaching relying on the latest technological developments.

Positive experiences from online ESP classes are also related to the availability of various learning materials uploaded to the learning platforms, and the use of video content. Posting course materials and the use of video clips in class had been practiced before the transition to online teaching due to the Covid-19 pandemic, but the results of this research strongly imply that such practices reached its full potential in virtual classroom. The conclusion is that the use of platforms and appropriate video materials are perceived as purposeful teaching aids for the optimization of students’ learning and should be insisted upon.

The findings of this study indicate that the achievement of the goals of teaching ESP online is negatively affected by certain psychological factors such as loss of concentration. Technical difficulties and a lack of in-person communication may also pose serious obstacles.

The conclusions also highlight a need for addressing the issues of large classes and inadequate classrooms in the traditional mode of teaching. Regardless of the unfavourable technical aspects of online teaching, the respondents recognized the advantages of teaching small classes and good acoustics.

Computer-mediated ESP teaching, as documented by the study, is beneficial and student-friendly in terms of accessibility and convenience. However, it adversely affects in-person communication, which consequently results in neglecting the development of social, pragmatic and intercultural language competence. The conclusions we have reached can be the guidelines for reshaping teaching strategies and implementing new activities and approaches in ESP in the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis.

Acknowledgements

This paper was written as part of the project Humans and Society in Times of Crisis, financed by the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade, the Republic of Serbia.

Conflict of interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Список литературы Teaching ESP online: a guide to innovation in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis

- Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Carbone, E. (1998). Teaching large classes: Tools and strategies (Vol. 19). Sage. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483328270

- Cooper, J. L., & Robinson, P. (2000). The argument for making large classes seem small. New directions for teaching and learning, 2000(81), 5-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.8101

- Forrester, A. (2020). Addressing the challenges of group speaking assessments in the time of the Coronavirus. International Journal of TESOL Studies, 2(2), 74-88. https://doi.org/10.46451/ijts.2020.09.07

- Harasim, L. M., Hiltz, S. R., Teles, L., & Turoff, M. (1995). Learning networks: A field guide to teaching and learning online. MIT press.

- Hiltz, S. R. (1986). The “virtual classroom”: Using computer-mediated communication for university teaching. Journal of communication, 36(2), 95-104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1986.tb01427.x

- Hyland, K. (2002). Specificity revisited: How far should we go now?. English for specific purposes, 21(4), 385-395. https://doi. org/10.1016/S0889-4906(01)00028-X

- Lapadat, J. C. (2002). Written interaction: A key component in online learning. Journal of computer-mediated communication, 7(4), JCMC742. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2002.tb00158.x

- Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(1), 68-88. http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v7i1.1864

- The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assesment, Strassbourg: Council of Europe and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://rm.coe.int/16802fc1bf

- Vujović, A. (2010). Interculturality in teaching language for specific purposes. Kragujevac, Nasleđe, 7(15-1), 207-215.