The Affective Turn in Metamodernist Fiction and “New Sincerity”

Автор: Chemodurova Z.M.

Журнал: Вестник Волгоградского государственного университета. Серия 2: Языкознание @jvolsu-linguistics

Рубрика: Главная тема номера

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.23, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The aim of the article is to analyze pragmatic strategies and mechanisms to enhance narrative empathy, the key notion of metamodernist fiction that distinguishes it from postmodernist and modernist literary texts. The article postulates foregrounding of emotivity markers in metamodernist texts as a linguistic manifestation of the cultural logic of "new sincerity" in the contemporary fiction that is characterized by the lack of an explicit ludic modality of postmodernist fiction and by stressing means of producing emotional resonance on the part of the reader and their active perspective-taking. The article makes an original contribution to cognitive stylistics, multimodal studies and narratology by hypothesizing polyphony of narrative "voices", second-person narrative and visual foregrounding as effective pragmalinguistic tools of triggering emotive and cognitive empathy that increases reader's immersion in metamodernist fictional worlds. Using the novels by M. Porter and J. Egan, the short stories by J.S. Foer and D. Eggers as its case studies, the article proves the relevance of viewing the "new sincerity" concept as a driving force behind the authorial empathy towards fictional characters, which enhances emotionogenic potential of metamodernist fiction and contributes to reader's engagement with modeled emotive situations. The findings of the research testify to the importance of further research into "new sincerity" and potential mechanisms of inducing reader's empathy which is justly considered a powerful instrument for promoting social interaction, helping readers of all ages to inhibit aggression and develop understanding of others' motives, emotions and desires.

Metamodernist fiction, narrative empathy, emotionogenic potential, new sincerity, emotional resonance, perspective-taking, visual foregrounding

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149145971

IDR: 149145971 | УДК: 81’42:821 | DOI: 10.15688/jvolsu2.2024.2.7

Текст научной статьи The Affective Turn in Metamodernist Fiction and “New Sincerity”

DOI:

Since the moment when Linda Hutcheon announced the “demise” of postmodernism [Hutcheon, 2002] quite a number of new terms have been offered to describe an emerging cultural logic which has obviously come to replace the postmodern cultural paradigm: “Amongst the suggestions are notions as diverse as: ‘hypermodernism’ (G. Lipovetsky), which stresses consumerism; ‘digimodernism’ (A. Kirby), which foregrounds digitisation; a ‘postpostmodern’ realist ethics (R. McLaughlin); ‘cosmodernism’ (Ch. Moraru) and ‘planetariness’ (Amy Elias, Ch. Moraru) which emphasize globalisation; the ‘Anthropocene’ (A. Trexler) with its environmental concern” [Gibbons, Vermeulen, van den Akker, 2019, p. 172].

In the seminal paper published by Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker in 2010 the notion of metamodernism as a new label for the post-postmodern condition was proposed. The scholars suggest that “ontologically, metamodernism oscillates between the modern and the postmodern. It oscillates between a modern enthusiasm and a postmodern irony, between hope and melancholy, between naıvete and knowingness, empathy and apathy, unity and plurality, totality and fragmentation, purity and ambiguity. Indeed, by oscillating to and fro or back and forth, the metamodern negotiates between the modern and the postmodern” [Vermeulen, van den Akker, 2010].

One of the key concerns of the past two decades for cognitive poetics, stylistics, and narratology related to what has become known as “metaxis” or the state “in-between” modernism and postmodernism [Vermeulen, van den Akker,

2010] is the question about the correlation of fiction and reality in metamodernist literature. Has the postmodernist “panfictionality” [Ryan, 2019], the “collapsing border between fact and fiction” as a dominant feature of postmodernist literary texts receded into the background of contemporary fiction, that might now let modern readers engage with the plot emotionally? Another crucial question related to this new cultural and philosophical paradigm is raised in text linguistics, Cultural studies and Literary studies and concerns a variety of ways that are used by modern writers to represent the concept of “new sincerity” in fiction. So far very few studies have offered any insights into the linguistic manifestation of this phenomenon which has now become associated with the paradigm shift and metamodernist fiction, in particular.

The aim of this article, therefore, is to analyze the pragmalinguistic and narrative aspects of constructing and interpreting the 21st century fiction, disclosing the linguistic features of “new sincerity” and/or “postirony” concept [Hoffmann, 2016, p. 11] which reflect a certain metamodernist shift from the pervasive irony, typically postmodernist and disruptive for the illusionbuilding process in a literary text, to the enhanced role of narrative empathy contributing to the readers’ immersion in a fictional world.

One of the relevant research tasks of this article then is an examination of the affective turn, potentially related to the “new sincerity” logic and characteristic of many contemporary literary texts. This affective turn is brought about by various pragmatic strategies and narrative mechanisms which, though formally easily identifiable as postmodernist, help to intensify a “reality effect – a performance of, or insistence on, reality” [Gibbons, Vermeulen, van den Akker, 2019, p. 174].

The reason for the authorial intention to describe narrative situations that foreground emotions, often such painful emotions as grief, or anger, and to activate intense narrative empathy of the readers, is hypothesized in this article as the willingness of modern writers to give up, at least to a greater degree, what has come to be known as a postmodernist ludic attitude [Chemodurova, 2017]. When defining postmodernism Umberto Eco produces a very memorable illustration of the ironic/playful mode of text articulation when he writes in the “Postscript to the Name of the Rose”: “I think of the postmodern attitude as that of the man who loves a very cultivated woman and knows he cannot say to her, ‘I love you madly’, because he knows that she knows (and that she knows that he knows) that these words have already been written by Barbara Cartland. Still, there is a solution. He can say, ‘As Barbara Cartland would put it, I love you madly’. At this point, having avoided false innocence, having said clearly that it is no longer possible to speak innocently, he will nevertheless have said what he wanted to say to the woman: that he loves her, but he loves her in an age of lost innocence. If the woman goes along with this, she will have received a declaration of love all the same. Neither of the two speakers will feel innocent, both will have accepted the challenge of the game of irony...” [Eco, 1984, pp. 66-67].

Now the focal point of metamodernist cultural logic seems to be centered around suspending skepticism and overall denial of hope and attempting to reconstruct “an age of innocence” with its “longing for sincerity” [Pignagnoli, 2016] when explicit emotiveness of the text might be viewed as an integral part of author-reader relationship.

In other words, metamodernist aesthetics is said to oscillate between “postmodern irony (encompassing nihilism, sarcasm, and the distrust and deconstruction of grand narratives, the singular and the truth) and modern enthusiasm (encompassing everything from utopism to the unconditional belief in Reason)” [Vermeulen, van den Akker, 2010] including postmodernist fragmentation, ludic elements and metafictional devices but foregrounding “a dialectic of sincerity”

initially described in the manifesto essay by David Foster Wallace in 1993 [Kelly, 2014]. If we agree with the assertion by M. Epstein that the fiction at end of the 20th century is characterized by the lack of powerful and sincere emotions and this literary condition explains what he calls quite poetically “the emotional famine” experienced by readers [Epstein, 1992] then his idea about the onset of a new Age of Sentimentality is likely to be quite prophetic too. According to him, this new Era of Sentimentality or Sensitivity will differ from its 18th century precursor and will inevitably incorporate all the emotional complexity of the 19th and 20th century narratives and experience all the “carnivalesque cicles, irony and black humour” of the postmodernist period [Epstein, 1992].

Thus, another relevant objective of this article is to examine a hypothesis according to which the logic of “new sincerity” is represented in metamodernist fiction through pragmatic strategies and narrative mechanisms used by modern authors in their attempt to increase the emotionogenic potential of their fiction introducing highly emotive narrative situations and provoking readers’ narrative empathy.

Materials and methods

Apart from an obvious challenge of identifying inherent features of metamodernism as a dominant cultural condition of the 21st century it is deemed important to analyze a metamodernist literary text from an interdiscilplinary perspective that will allow to draw some conclusions relevant to cognitive linguistics, stylistics, narratology, and multimodal studies. The methodology underlying the present research, therefore, comprises elements of stylistic, cognitive and linguo-semiotic analyses, with the phenomena of narrative empathy and text emotivity placed in the focus of research attention.

I have chosen the novels by Max Porter “Grief is the Thing with Feathers”, by Jennifer Egan “A Visit from the Goon Squad”, short stories by Jonathan Safran Foer and Dave Eggers as the case studies to explore the pragmatic mechanisms crucial for intensifying readers’ narrative empathy which, in my opinion, contributes to the emergence of this new quality of textual emotivity different from the previous postmodernist aesthetics. All the works I examine come from a very brief span of the first two decades of the 21st century and represent some typical properties of metamodernism which appear noteworthy.

Results and discussions

Contemporary approaches to narrative empathy

Nowadays empathy is described as “a ubiquitous concept in areas ranging from politics, law, and business ethics to medical care and education” [Lindhé, 2016, p. 19]. In this article I hypothesize an increase in narrative empathy in metamodernist fiction of the 21st century as an important linguistic manifestation of the concept of “new sincerity”, as a way to compensate for the ‘emotional famine”, experienced by the readers of postmodernist fiction indulging in reality vs. fiction games and self-reflexivity.

The phenomenon of empathy first attracted attention of psychologists, linguists and narratologists at the turn of the 20th century when, according to one of the leading modern experts on empathy, Suzanne Keen, “the experimental psychologist E.B. Titchener translated as “empathy” aesthetician Theodor Lipps’ term Einfühlung (which meant the process of “feeling one’s way into” an art object or another person). Notably, Titchener’s 1915 elaboration of the concept in Beginner’s Psychology exemplifies empathy through a description of a reading experience: “We have a natural tendency to feel ourselves into what we perceive or imagine. As we read about the forest, we may, as it were, become the explorer; we feel for ourselves the gloom, the silence, the humidity, the oppression, the sense of lurking danger; everything is strange, but it is to us that strange experience has come” [Keen, 2006, p. 209]. As we can see, the concept of empathy started at once to be associated with the notion of imagination and this theoretical contention found its development many decades later, with the onset of the era of breakthroughs in cognitive psychology and neuroscience and the discovery of the so-called “mirror neurons”. One of the dominant approaches to the phenomenon of empathy at the beginning of the 21st century is known as the Simulation Theory, and it postulates a certain mechanism of simulation: “imagining what we would feel if we were in the other’s situation. On a relatively complex, high level, we simulate the other’s state in our own mind and then arrive at the knowledge of how the other feels by imitating the other’s behavior in our mind and then projecting our own mental process onto the other. According to ST, we play through, via a first-person perspective, being in the other’s situation and utilize our own mental mechanisms to generate thoughts, beliefs, desires, and emotions” [Schmetkamp, Vendrell Ferran, 2019].

Empathy nowadays is believed to be our “natural tendency to share and understand the emotions and feelings of others in relation to oneself, whether one actually witnesses another person’s expression, perceived it from a photograph, read about it in a fictive novel, or imagined it” [Decety, Meyer, 2008, p. 1053].

Leaving aside the debate around the neurolinguistic mechanisms triggering empathy (for an overview, see: [Decety, Meyer, 2008; Schmetkamp, Vendrell Ferran, 2019]), in this research I will focus on just one kind of empathetic behaviour – narrative empathy, or empathy towards fictional characters, which, undoubtedly, has very significant implications for promoting social interaction, helping readers of all ages to inhibit aggression and develop understanding of others’ motives, emotions and desires.

Narrative empathy is defined by Suzanne Keen as “the sharing of feeling and perspectivetaking induced by reading, viewing, hearing, or imagining narratives of another’s situation and condition. Narrative empathy plays a role in the aesthetics of production when authors experience it; in mental simulation during reading, in the aesthetics of reception when readers experience it, and in the narrative poetics of texts when formal strategies invite it. Narrative empathy overarches narratological categories, involving actants, narrative situation, matters of pace and duration, and storyworld features such as settings” [Keen, 2013]. Though narrative empathy is agreed upon by most scholars [Keen, 2007] to be viewed as both cognitive and affective, there’s still a number of controversies persisting as to the scope of narrative empathy – in particular, whether we should distinguish between narrative feelings and narrative empathy (see, e.g.: [Miall, Kuiken, 2002]), and if character identification should be viewed as a separate though definitely related phenomenon (see the discussion in: [Koopman, 2016]).

In my approach to the issue of empathy I side with the conclusions drawn by Suzanne Keen in her ground-breaking work “Empathy and the Novel” [2007] and treat the phenomenon of narrative empathy as an umbrella term which includes diverse aspects such as readers’ perspective-taking, character identification and narrative emotions. The question which is of a special interest for this work concerns the correlation between readers’ immersion in the text, normally associated with the fictional game of make-believe [Walton, 1991], and the onset and intensity of empathy. Notably, both modernist and postmodernist texts are well-known for their techniques of creating aesthetic distancing which might hinder illusion-building and, consequently, according to most scholars, impede narrative empathy, slow down readers’ identification with the fictional characters and prevent them from taking protagonist’s perspective, experience authentic and profound emotions.

The hypothesis of this article is grounded in several significant distinctions between modernist and postmodernist fictional ontology and epistemology, elaborated by Brian McHale in his seminal monograph “Constructing Postmodernism” [1992]. According to his observations, though modernist fiction has often been criticized for the “unreliability of characters’ visions or accounts of the external world” [McHale, 1992, p. 64], readers nevertheless will be able to “reconstruct, first, the immediate ‘reality’ – objects and persons in the character’s field of perception, his actions and those of others, etc.; secondly, absent ‘reality’ – objects, persons and events present in the character’s memory or, more dubiously, in his speculative projections or imaginings; and thirdly, by extrapolation, the general material culture, more and norms, etc.” [McHale, 1992, pp. 64-65]. In other words, the most important difference lies in the fact that, unlike postmodernist fiction with its endless metafictional games, impossible fictional worlds and inherent paradoxes and contradictions, constantly disrupting the process of illusion construction, “the ontological stability of external reality seems basic to modernist fiction” [McHale, 1992, p. 65]. It is this stability of the constructed fictional universe that promotes the engagement of the reader with the fictional text procuring the empathetic effect and helping the reader experience a variety of emotions, both narrative and aesthetic ones.

Thus, taking Brian McHale’s cue, in the following paragraphs I am going to analyze mechanisms and strategies which, though initially practiced by modernist and postmodernist authors alike, tend to model the fictive worlds, ontologically stable, lacking explicit ludic traps and conundrums so common in postmodernist texts, and hence provoking empathetic responses from addressees. Such fictive worlds are now believed to be constructed in metamodernist fiction and demonstrate this “longing for sincerity” in this new “age of sentimentality” when readers encounter narrators and protagonists exposing them to a host of negative and positive emotions represented in fiction without illusion-shattering postmodernist irony, sarcasm and black humour.

Multiperspectivity and the reader’s emotional resonance in metamodernist fiction

The aim of this section is to examine a typical modernist device of creating a polyphony of narrative voices, in line with M.M. Bakhtin’s ideas, and to analyze its empathy-inducing potential in metamodernist fiction. As one of the foremost experts on postmodernism claims when analyzing Ulysses, “it is in the light of these complementary functions of inwardness and openness, centripetal movement and centrifugal movement, that we must view modernist innovations in the presentation of consciousness” [McHale, 1992, p. 44]. This multiperspectivity, though somewhat challenging for unsophisticated readers and creating a defamiliarizing effect, is still firmly grounded in external reality which seems to be one of the major factors promoting reader engagement with the constructed fictional world and allowing for their perspective-taking. As Neary notes, according to Toolan, «“furnishing the textual means with which the reader can ‘see into’ or see along with that character’s imagined consciousness”, a circumstance achieved through authorial depiction of “a credible scene or situation”, alongside the provision of readerly access to the characters internal perspective» [Neary, 2010, p. 6].

Metamodernist fiction tends to utilize this overarching modernist strategy of “mobile consciousness” (McHale) combining it with a typical postmodernist narrative fragmentation as readers discover, for example, from the start of the short novel by Max Porter “Grief is the Thing with Feathers” where we are exposed to the sad story of a tragic loss and overwhelming grief narrated by three voices: Dad, Boys and the Crow:

-

(1) BOYS

There’s a feather on my pillow.

Pillows are made of feathers, go to sleep.

It’s a big, black feather.

Come and sleep in my bed.

There’s a feather on your pillow too.

Let’s leave the feathers where they are and sleep on the floor.

DAD

Four or five days after she died, I sat alone in the living room wondering what to do. Shuffling around, waiting for shock to give way, waiting for any kind of structured feeling to emerge from the organisational fakery of my days. I felt hung-empty. The children were asleep. I drank. I smoked roll-ups out of the window. I felt that perhaps the main result of her being gone would be that I would permanently become this organiser, this list-making trader in cliches of gratitude, machine-like architect of routines for small children with no Mum. Grief felt fourth-dimensional, abstract, faintly familiar. I was cold (Porter, 2016, p. 1).

The tragic loss of the wife and the bereaved and grieving husband destined to bring his boys up single-handedly is a powerful emotionally contagious narrative situation introduced to the readers in the strong position of the beginning. The emotive concept of GRIEF, mentioned in the allusive title of the novel, is represented by a number of lexical means in the Dad’s interior monologue drawing readers into imagining an emotive situation where both cognitive and affective empathy are likely to be invoked simultaneously as we are mentally placing ourselves in the situation of the father facing his orphaned kids. The heteroglossia of the first fragment – a father-boys dialogue – seems to represent a regular talk of the parent with his kids but for the insistent use of the lexical item “feather” repeated 5 times and resonating with the title of the novel. The famous poem by Emily Dickinson “Hope is the Thing with Feathers”, inevitably coming to mind of contemporary readers, well-familiar with various intertextual games of modernists and postmodernists, sets the antithesis of the two emotive concepts crucial for the empathetic effect of the novel. The concept GRIEF is represented by various linguistic means: on the lexical level we find the lexical units “died”, “shock”; the reflector of this “emocentric microcontext” [Filimonova, 2001] defines his state with the help of the kinesthetic description – “shuffling around” – and the expressive adjectives “hung-empty”, “fourth-dimensional, abstract”. Readers’ ability to understand the situation of someone feeling shell-shocked is supported on the cognitive level by our affective empathy, i.e. “feeling what the other is feeling” [Chew, Mitchell, 2016, p. 128]. The epigraph of the novel that synergetically models a highly emotive context right from the beginning of the narration based on the three core emotive concepts LOVE, HOPE and GRIEF, is also in the strong position, it creates yet another association with Emily Dickenson’s oeuvre (Porter, 2016, p. 1):

e fto W

That Love is all there is, Q (К О V^ Is all we know of Love;

It is enough, the f reigh t should be • c ^ ^^

Proportioned to the groove.

Emily Dickinson

The graphic foregrounding of the word “Crow” scribbled over the four nominal elements in the quatrain, crossed-out but visible, initiates readers into a heart-breaking story of the traumatized family visited by a mythical bird – one of the narrators of the story – which comes to help them heal. The unique fictional world of this debut novel by Max Porter is playful and magically realistic, intertextually complex and emotionally impactful, very sad and filled with the author’s compassion towards his characters. Partially based on the author’s personal experience of losing his father at the age of 6 [Crown, 2015] and having to come to terms with this tragic change in his life, the book, apart from being a talented tribute to E. Dickinson’s and Ted Hughes’ (the source of Crow inspiration) literary geniuses, is also a typical sample of metamodernist oscillation between modernist and postmodernist strategies. Prolific language games, the image of the Crow – a figment of the Dad’s imagination representing a multifaceted figure of a postmodernist trickster and a mythical device, – as well as narrative fragmentation, time loops and non-linear chronology might well characterize the book as postmodernist. What turns it into a new generic form, which might be called metamodernist, is the potential emotional resonance generated by the author’s heartfelt empathy towards his characters reflected in the polyphonic structure of the narrative, producing a powerful immersive effect on the readers and, thus, representing the cultural logic of “new sincerity” in fiction:

-

(3) CROW

In other versions I am a doctor or a ghost. Perfect devices: doctors, ghosts and crows. We can do things other characters can’t, like eat sorrow, un-birth secrets and have theatrical battles with language and God. I was friend, excuse, deus ex machina, joke, symptom, figment, spectre, crutch, toy, phantom, gag, analyst and babysitter.

I was, after all, ‘the central bird... at every extreme’. I’m a template. I know that, he knows that. A myth to be slipped in. Slip up into.

Inevitably I have to defend my position, because my position is sentimental. You don’t know your origin tales, your biological truth (accident), your deaths (mosquito bites, mostly), your lives (denial, cheerfully). I am reluctant to discuss absurdity with any of you, who have persecuted us since time began. What good is a crow to a pack of grieving humans? (Porter, 2016, p. 12).

This mythical character, an embodiment of eternal grief and hope simultaneously, whose appearance in the life of the family is accounted for by the Dad’s scholarly paper in progress at the time of his wife’s demise “Ted Hughes’ Crow on the Couch: A Wild Analysis’’ (Porter, 2016, p. 27), is witty, playful, and allusive. He claims that he is ‘the central bird... at every extreme’, thus echoing the words of Ted Hughes himself: “Crows are the central bird in many mythologies. The crow is at every extreme, lives on every piece of land on earth, the most intelligent bird’’ [Heinz, 1995].

The Crow stays with the family until grief slowly and inevitably subsides and gives way to hope, love and fond memories:

-

(4) BOYS

We seem to take it in ten-year turns to be defined by it, sizeable chunks of cracking on, then great sinkholes of melancholy.

Same as anyone, really.

We used to think she would turn up one day and say it had all been a test.

We used to think we would both die at the same age she had.

We used to think she could see us through mirrors.

We used to think she was an undercover agent, sending Dad money, asking for updates.

We were careful to age her, never trap her. Careful to name her Granny, when Dad became Grandpa.

We hope she likes us (Porter, 2016, p. 96).

Our emotional resonance as readers invited to empathize with someone grief-stricken and hurting is therefore intensified in this metamodernist novel as we are allowed access through perspecting-taking to the rawest emotional moments represented by the author with humour, warmth and sincerity simultaneously. In example (4) Max Porter induces our empathy by resorting in one of the final Boys’ fragments to a flashforward letting the reader share some potential developments in the boys’ life and drawing a hopeful picture of their maturing. The author employs parallelism, anaphoric repetition of the “used to think” structure, facilitating a transition from the description of habitual actions in the past to a much later moment in the boys’ lives when they collectively utter an emotive statement of the grown-up sons who have already fathered their own kids “We hope she likes us”. The convergence of stylistic devices foregrounds quite effectively a constitutive feature of the metamodernist literary text: its increased emotionogenic potential with the focus on readers’ immersion in the fictive world and empathetic effect produced by its polyphonic narrative structure.

The second person in the metamodernist narrative and perspective-taking

As has become unequivocally accepted in modern text linguistics and narratology, “ You , in modern English the only pronoun of direct address, always implies an act of communication. The most reliable sign of narratorial ‘voice’, it compels the reader, by its very presence in a text, to hypothesize a circuit of communication joining an addressor and an addressee” [McHale, 1992, p. 89].

Postmodernist writers exploited a “potential ambiguity” (McHale) of the second person in the narrative structure, playfully conflating different communicative circuits where “you” can function. Thus, according to Brian McHale, in the “Gravity’s Rainbow” by Thomas Pynchon, a canonical postmodernist novel, the reader faces a challenge of decoding transgressive uses of this pronoun, whenever “an extradiegetic narrator pretends to address one of “his” or “her” characters”, or when “an extra-diegetic narrator pretends to address the empirical reader directly”. The intentional ambiguity as to who is addressing whom might be created in case of the so-called narratorial apostrophe, i.e. when “the extradiegetic narrator apostrophizes a character” [McHale, 1992, pp. 93-101]. Even when we readers seem to encounter the case of the interior dialogue with one character addressing another, imagined character, in postmodernist fiction that might increase an uncertainty and indefiniteness associated with this literary movement. One of the most exemplary narrative conundrums, apart from the above mentioned novel by Pynchon, was created by Robert Coover in his short stories “The Babysitter” and “Quenby and Ola, Swede and Carl” where the reader is left nonplussed till the end as to the “reality” or impossibility of the fictive events described, thus experiencing an explicit ludic effect of postmodernist fiction which, though intellectually entertaining might be causing in many readers the “emotional famine” that Mikhail Epstein has associated with the postmodernist era.

In metamodernist narratives the second person seems to be utilized quite actively not to mystify or befuddle the reader but to involve them in the fictional game of make-believe, inducing intense empathy through perspective-taking without the ubiquitous ironic stance of postmodernist ludic fiction.

Dave Eggers is an American novelist and editor whose best-selling autofiction “A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius” (2000) signified a certain transition from experimental mechanisms of postmodernism to subjectivity and the attempt at representing intersubjectivity as an important feature of metamodernist poetics.

Dave Eggers uses the second-person narrative in his short stories to emotionally and cognitively involve readers in the representational game. His short story “Should You Lie About Having Read That Book?” (2005) in the strong position of the title offers the reader a moral dilemma in the form of the rhetorical question, which many addressees will find familiar, thus triggering an initial empathetic reaction:

-

(5) How could anyone possibly know you hadn’t? You are on your way to the marina, where you will board a sailboat owned by a friend of a friend, and on this boat, among nine sailing-people total, will be a person who has written a book that everyone has read, and that you should have read, but which you have not read.

The book was written three years ago, and is being taught and discussed with great seriousness by people who consider themselves very serious people. You are driving to the marina with your friend Terry, who stutters so dramatically that he drools, and it was he who told you, two weeks ago, that, if you wanted to go sailing this day, you needed to read this book, because the author likes to talk about his book and can sniff out non-readers miles away (Eggers).

The story appears to be a convincing example of the oscillation between postmodernist and modernist pragmatic strategies of the fictional world organization, which is considered to be a typical metamodernist characteristic, as its ironic tone does not disrupt the process of illusionbuilding and therefore does not preclude the emergence of empathy. The performativeness, nowadays associated with a new cultural logic of metamodernism [Gibbons, Vermeulen, van den Akker, 2019], or the “reality” effect, is created with the help of the Present Tenses, projecting a reader’s immediate immersion in the constructed fictional world:

-

(6) “You consider yourself an extraordinary liar, and thus you assumed, waking up today, that you would lie and would be fine with your lying. But now you’re nervous. Will you be a good-enough liar even if slightly seasick? Can you lie on an empty stomach – if you need to vacate your interiors over the bow?

You board the boat, still unsure of how you’ll handle the task, but your concern, in the end, is unwarranted, because just out of the harbour, this boat, and its nine passengers, are devoured, whole, by a giant squid. In the Bible they called these creatures leviathans, and they are as much a nuisance now as then. To report a sighting of these giant squids/leviathans, send a selfaddressed, stamped envelope to 826 Valencia Street, San Francisco, CA 94110 USA. Thank you (Eggers).

The emotive situation of nervousness so skillfully modeled by D. Eggers with the help of the second person narrative, rhetorical questions, the repetition of the emotive vocabulary (“nervous”, “unsure”, “concern”) contributes to our perspective-taking up to the denouement of the story that offers a brilliant and typically postmodernist final twist. The effect of defeated expectancy as one of the favoured postmodernist mechanisms of foregrounding [Chemodurova, 2019] used in the strong position of the ending of this story reminds us readers that metamodernist fiction might be relying quite actively on both modernist and postmodernist strategies for its aesthetic impact. The use of the explicitly ludic ending, the tone of which suddenly strikes us as darkly humorous, and not unlike Donald Barthelme’s ironic narratives, brings us back to the long-lasting debate focusing on the role of foregrounding in inducing/reducing narrative empathy (see, e.g.: [Miall, Kuiken, 2002; Keen, 2007]). Though there are still no conclusive scientific data testifying to the effectiveness of the foregrounding phenomenon in increasing narrative (emotive and cognitive) empathy, I share the contention of a number of scholars that foregrounding is instrumental in triggering and sustaining narrative empathy as various mechanisms of focusing readers’s attention on the defamiliarized fragments of the text slow down the process of reading, ignite a readers’ keen interest in the foregrounded textual elements, thus contributing to the readers’ enhanced emotional and cognitive involvement with the text.

The short story by Jonathan Safran Foer “Here We Aren’t, So Quickly” serves well to illustrate this point as the author of the bestselling novel “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close”, a fine example of metamodernist fiction, resorts to several foregrounding mechanisms from the start. The title of the short story is obviously based on the “alienation” effect involving the reader into the language game they will have to puzzle out:

-

(7) I was not good at drawing faces. I was just joking most of the time. I was not decisive in changing rooms or anywhere. I was so late because I was looking for flowers. I was just going through a tunnel whenever my mother called. I was not able to make toast without the radio. I was not able to tell if compliments were backhanded. I was not as tired as I said.

You were not able to ignore furniture imperfections. You were too light to arm the airbag. You were not able to open most jars. You were not sure how you should wear your hair, and so, ten minutes late and halfway down the stairs, you would examine your reflection in a framed picture of dead family. You were not angry, just protecting your dignity (Foer).

The interior dialogue of an unnamed first-person narrator addressing his wife is an exemplary case of coupling, another mechanism of foregrounding [Chemodurova, 2019] when the structural parallelism highlights an emotional impact of the narration immediately engaging addressees in this evocative life drama. The story boasting of narrative fragmentation and nonlinear chronology, nevertheless, induces empathy from the first paragraphs as the reader experiences no uncertainty putting themselves in the situation of the husband and sharing a variety of emotions triggered by the narrative scenario of a married life:

-

(8) When you screamed at no one, I sang to you. When you finally fell asleep, the nurse took him to bathe him, and, still sleeping, you reached out your arms.

He was not a terrible sleeper. I acknowledged to no one my inability to be still with him or anyone. You were not overwhelmed but overtired. I was never afraid of rolling over onto him in my sleep, but I awoke many nights sure that he was underwater on the floor. I loved collapsing things. You loved the tiny socks. You were not depressed, but you were unhappy. Your unhappiness didn’t make me defensive; I just hated it. He was never happy unless held. I loved hammering things into walls. You hated having no inner life. I secretly wondered if he was deaf. I hated the gnawing longing that accompanied having everything. We were learning to see each other’s blindnesses. I Googled questions that I couldn’t ask our doctor or you (Foer).

Sincerity is likely to be a driving emotion behind this imagined conversation of the narrator and his diegetic addressee inviting the reader to unravel a complexity of feelings that spouses might experience over a long span of years they have been married.

The birth of a son, parental anxiety, tenderness and love, unhappiness and fear – we are exposed to a wide range of narrated feelings resonating with many readers emotively and cognitively thanks to the mechanisms of foregrounding, such as coupling and the convergence of stylistic devices. The consistent use of parallel constructions focuses readers’ attention on the key words

“loved”, “hated”, “unhappy”, “happy” creating the antithesis that reflects ups and downs of everyday life, and a seemingly haphazard enumeration of events enhances an empathetic effect of a sincere and passionate “voice” ringing very true to life.

Visual foregrounding and character identification in metamodernist fiction

The first two decades of the 21st century have witnessed a significant spike in the publication of the so-called multimodal literary texts, i.e. visually unconventional, hybrid fiction which uses “images, colour, special layout and typography for its meaning-making” [Norgaard, 2014, p. 481].

The hypothesis of this article also postulates a connection between the increased emotionogenic potential of metamodernist fiction and an active use by many contemporary writers of a strategy of visual foregrounding in addition to what is commonly known as “graphical imagery”. In my earlier works I propose a definition of visual foregrounding as “a formal feature of modern texts focusing readers’ attention on various unbound semiotic resources contributing to the transmodal meaning-making process and performing a range of functions in the narrative” [Chemodurova, 2021, p. 6]. I suggest that it might be helpful for the effective analysis of a wide range of experimental fiction to draw a distinction between a mechanism of graphical foregrounding which traditionally, over several centuries, has been based on the creative potential of “bound semiotic resources”, and a strategy of visual foregrounding, when images, photographs, pictures, emojis, tables are introduced into the fictional world of a contemporary novel to enhance its expressivity, emotiveness and narrative empathy, very often making character idetification more effective for a new generation of readers [Chemodurova, 2022].

Metamodernist fiction emerging at the turn of the 21st century owes much of its increased empathetic impact to the combined use of graphical and visual foregrounding when both verbal and visual elements in multimodal clusters cohere and serve as important graphical/visual props in the game of imagination [Chemodurova,

2021] arresting readers’ attention, producing defamiliarizing effect soon to be followed by a refamilization afforded by the foregrounded textual fragments.

One of the important challenges related to a further probing into the nature of metamodernist fiction, and multimodal metamodernist fiction in particular, as multimodal stylistics seems to be on the rise research-wise, has to do with analyzing differences between a postmodernist use of bound and free semiotic resources in literature and a metamodernist method of employing such resources.

The findings of my research into both postmodernist and metamodernist hybrid fiction appear to support a general hypothesis postulated in this article about a less explicit representation of the category of ludic modality [Chemodurova, 2017] in metamodernist fiction compared to postmodernist novels many of which have been described by B. McHale as “concrete prose” [McHale, 1992]. K. Vonnegut, D. Barthelme, John Barth, Italo Calvino are among the most acclaimed postmodernist writers to have playfully utilized various semiotic modes and foregrounded an elusive boundary between reality and fiction. The process of oscillation that characterizes metamodernism is typically relevant to the issue of multimodality in contemporary metamodernist fiction. The ludic function of visual foregrounding has not disappeared completely as it is inherent in the ontology of fiction (see for the analysis of the concept of play in fiction: [Chemodurova, 2017]) but it has been somewhat superceded by the emotive function, helping metamodernist writers to significantly increase narrative empathy and contributing to readers’ identification with fictional characters. In other words, visual foregrounding in multimodal metamodernist fiction does not disrupt the illusion-making process but acts as an effective semiotic mechanism of modeling contagious emotive situations.

As a case study for this section of the article I have chosen the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Jennifer Egan “A Visit from the Goon Squad” (2010), a remarkable work of fiction consisting of 13 loosely linked chapters (stories?) centering on many characters’ turbulent life from the 70s of the 20th century to the present moment and some 15 years into the near future.

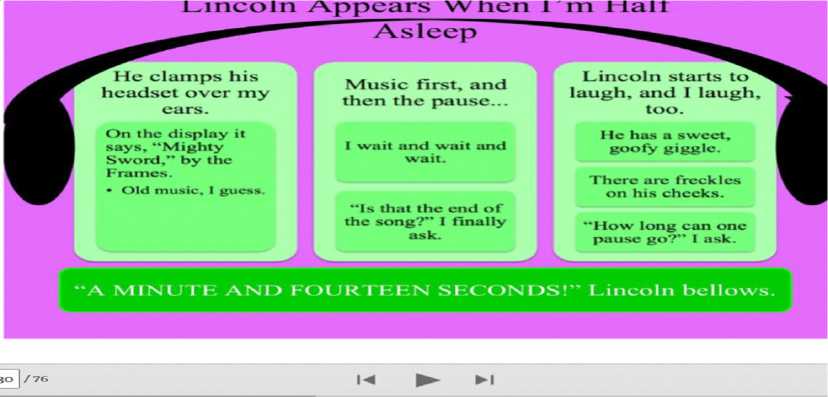

Chapter 12, which presents quite a disruption of an otherwise rather conventional narrative

ГЛАВНАЯ ТЕМА НОМЕРА strategy and might be viewed as an exemplary case of the defeated expectancy mechanism, is modeled entirely as a PowerPoint slide show made by Alison, a teenage daughter of Sasha, one of the book’s major characters. Alison prefers this digital medium to a traditional diary to describe the events of just two days in her life and the life of her parents and brother. The chapter is titled “Great Rock and Roll Pauses by Alison Blake” and seems to focus our attention at once on the theme of music, one of the central themes in the novel, and the key theme of the entire novel – that of Time, ruthless, irreversible and metaphorically described as a Goon.

Alison is characterized through her slides as a smart 12-year old kid, caring and protective of her 13-year old brother Lincoln, who seems to be suffering from a mild form of Asperger’s syndrome and whose main interest in life is music. The title of the chapter foregrounds his unusual focus on the length of pauses in various classic compositions, and this Lincoln’s hobby resonates brilliantly with the central theme of Time’s transience. This chapter is available on the author’s website A Visit From the Goon Squad – Jennifer Egan as a sample of the novel where readers’ immersive experience is intensified because of the audial component of the message, which enhances the effect of the multimodal resonance (see: [Chemodurova, 2021; 2022]).

The slide-show narrative of chapter 12, foregrounded visually and graphically, can be viewed as an emotional dominant of the whole novel, for the combination of various semiotic resources contributes to the increase in narrative empathy, helping us to identify emotionally with the members of the family making a real effort to cope with life’s challenges. Narrative fragmentation, which is here postmodernist par excellence, does not seem to prevent addressees from perspectivesharing and taking an active part in constructing a multimodal meaning of the text.

Warmth, tenderness and patience on the part of Alison, who loves her brother dearly, are represented with the epithets “sweet, goofy”, the key words “laugh” and “wait” and the choice of the green color for her slides (see Fig. 1) which often symbolizes “hope” and “life” in social semiotics [Almalech, 2014].

This chapter constitutes an emotional dominant of the novel that on the whole tends to portray rather self-destructive characters but in its multimodal section exposes readers to an empathetic analysis of family controversies and issues mixed with love and hope, thus, signaling a metamodernist shift of attitudes and a multimodal mechanism of representing “new sincerity” in fiction.

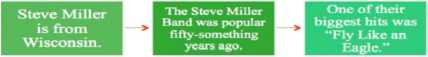

The emotive concept Love is foregrounded simultaneously visually, graphically, lexically with the help of repetition, intertextually, and multimodally, as readers are able to hear a few notes of the biggest hit by Steve Miller “Fly Like an Eagle”, which, as the boy believes, is one of his Dad’s favorite songs (see Fig. 2). Lincoln is endowed with an intuitive gift of feeling “time rushing past” through pauses, silence and a heartbeat of famous musicians. The conceptual metaphor “Time is a Goon” underpinning the semantic structure of the novel “A Visit from the Goon Squad” is represented here allusively in the refrain of the song:

Fig. 1. Slide 30 from Chapter 12: A Visit From the Goon Squad, by Jennifer Egan

Time keeps on slippin’, slippin’

Into the future

Time keeps on slippin’, slippin’

Into the future (Fly Like an Eagle by Steve Miller Band).

Conclusion

This article postulates the affective turn in medamodernist fiction. It examines various linguistic manifestations of the “dialectic of sincerity” first formulated by David Foster Wallace in 1993. This shift can be accounted for by the reflection in the writings of quite a number of contemporary authors of the cultural logic, known as “new sincerity”, which emerged at the end of the 20th century and has now spread across various discourse practices. My contention is that it is through the heightened attention to the phenomenon of narrative empathy in metamodernist fiction, both authorial empathy towards fictional characters and readers’ empathy stipulated by the narrative strategies that the “new sincerity” concept might be explored in text linguistics, cognitive stylistics, pragmalinguistics and narratology. One of the challenging questions this article strives to answer concerns a range of linguistic means of provoking narrative empathy typical of many contemporary novels.

They utilize both postmodernist and modernist pragmatic strategies and narrative mechanisms to encourage an active perspective-taking on the part of contemporary readers and induce their sharing of narrative emotions. The article hypothesizes a certain shift in metamodernist fiction from representing explicit ludic modality, characteristic of postmodernist fiction, to foregrounding the increased emotionogenic potential of metamodernist texts. I have attempted to analyze a polyphony of narrative “voices” and the strategy of creating multiple perspectives as one of the mechanisms of modeling emotive situations that trigger narrative empathy. Another important mechanism of inducing empathy examined in the article is an extensive use of the second-person pronoun in the 21st century fiction, which stimulates readers’ perspective-taking and contributes to their active involvement in the illusion-building process that is instrumental for generating narrative empathy and exposing readers to coherent representations of new-age sentimentality. The third strategy relevant to ensuring readers’ immersion in the fictional world constructed by metamodernist writers and contributing to addressees’ participation in the game of make-believe is visual foregrounding that has become quite wide-spread since the beginning of the 21st century. Multimodal clusters modeled in contemporary novels and acting as both graphical and visual props to involve readers in the game of imagination are shown to constitute emotional dominants of metamodernist fictional texts. Such dominants ensure quite effectively readers’ identification with fictional characters whose emotional experiences, often painful and intimate, constitute the focal point of metamodernist narratives.

Lincoln Wants to Say/Ends Up Saying:

“Hey Dad, there’s a partial silence at the end of ‘Fly Like an Eagle,’ with a sort of rushing sound in the background that I think is supposed to be the wind, or maybe time rushing past!”

Fig. 2. Slide 16 from Chapter 12: A Visit From the Goon Squad, by Jennifer Egan

Список литературы The Affective Turn in Metamodernist Fiction and “New Sincerity”

- Almalech M., 2014. Semiotics of Colour. New Semiotics Between Tradition and Innovation. Proceedings of the 12th World Congress of the International Association for Semiotic Studies (IASS/AIS) Sofia 2014, 16–20 September. Sofia, New Bulgarian University, pp. 747-758.

- Chemodurova Z.M., 2017. Pragmatika i semantika igry v angloyazichnoy postmodernistskoy proze XX–XXI vekov: avtoref. dis. ... d-ra filol. Nauk [Pragmatics and Semantics of Play in the 20th – 21st Сent. English-Language Proze. Dr. philol. sci. abs. diss]. Saint Petersburg. 40 p.

- Chemodurova Z., 2019. The Mechanisms and Types of Foregrounding in Postmodernist Fiction. Haase Ch., Orlova N., eds. English Language Teaching: Through the Lens of Experience. Newcastle, Cambridge Scholars Publ., pp. 277-295.

- Chemodurova Z.M., 2021. Visual Foregrounding in Contemporary Fiction. Voprosy kognitivnoy lingvistiki [Issues of Cognitive Linguistics], no. 5, pp. 5-15. DOI: 10.20916/1812-3228-2021-2-5-15

- Chemodurova Z.M., 2022. The Art of Storytelling in the Digital Age: A Multimodal Perspective. Vestnik Volgogradskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Seriya 2. Yazykoznanie [Science Journal of Volgograd State University. Linguistics], vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 110-120. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15688/jvolsu2.2022.6.9

- Chew E., Mitchell A., 2016. How Is Empathy Evoked in Multimodal Life Stories? Concentric. Literary and Cultural Studies, Sept., pp. 125-149. DOI: 10.6240/concentric.lit.2016.42.2.08

- Crown S., 2015. Max Porter: The Experience of the Boys in the Novel Is Based on My Dad Dying When I Was Six. The Guardian, Sept. 12.

- Decety J., Meyer M., 2008. From Emotion Resonance to Empathic Understanding: A Social Developmental Neuroscience Account. Development and Psychopathology, iss. 20, pp. 1053-1080.

- Eco U., 1984. The Postscript to the Name of the Rose. A Helen and Kurt Wolff Book. San Diego, New York, London, Harcourt Brace Yovanovich. 84 p.

- Epstein M., 1992. O novoy sentimentalnosti [On the New Sentimentality]. URL: https://www.emory.edu/INTELNET/es_new_sentimentality.html

- Filimonova O.E., 2001. Yazyk emotsii v angliyskom tekste (kognitivnyy i kommunikativnyy aspekti) [The Language of Emotions in the English Text (Cognitive and Communicative Aspects)]. Saint Petersburg, Herzen State Pedagogical University Publ. 259 p.

- Gibbons A., Vermeulen T., van den Akker R., 2019. Reality Beckons: Metamodernist Depthiness Beyond Panfictionality. European Journal of English Studies, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 172-189. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13825577.2019.1640426

- Heinz D., 1995. Ted Hughes, The Art of Poetry, No. 71. The Paris Review, iss. 134, Spring. URL: https://theparisreview.org/interviews/1669/the-art-ofpoetry-no-71-ted-hughes

- Hoffmann L., 2016. Postirony: The Nonfictional Literature of David Foster Wallace and Dave Eggers. London, Gazelle Book Services Ltd. 210 p.

- Hutcheon L., 2002. The Politics of Postmodernism. London, New York, Routledge. 232 p.

- Keen S., 2006. A Theory of Narrative Empathy. Narrative, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 207-236.

- Keen S., 2007. Empathy and the Novel. Oxford, Oxford Univ. Press. 275 p.

- Keen S., 2013. Narrative Empathy. The Living Handbook of Narratology. URL: http://lhn.sub.unihamburg.de/index.php/Narrative_Empathy. html

- Kelly A., 2014. “Dialectic of Sincerity: Lionel Trilling and David Foster Wallace.” Post45. Peer Reviewed. URL: http://post45.research.yale.edu/2014/10/dialectic-ofsincerity-lionel-trillingand-david-foster-wallace

- Koopman E.M., 2016. Effects of “Literariness” on Emotions and on Empathy and Reflection After Reading. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 82-98. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000041

- Lindhé A., 2016. The Paradox of Narrative Empathy and the Form of the Novel, or What George Eliot Knew. Studies in the Novel, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 19-42.

- McHale B., 1992. Constructing Postmodernism. London, New York, Routledge. 342 p.

- Miall D.S., Kuiken D., 2002. A Feeling for Fiction: Becoming What We Behold. Poetics, vol. 30, pp. 221-241.

- Neary C., 2010. Negotiating Narrative Empathy in Gahndis Life-Writing. The Language of Landscapes. PALA. Conference Proceedings. Genoa, Univ. of Genoa, pp. 2-25.

- Norgaard N., 2014. Multimodaly and Stylistics. Burke M., ed. The Routledge Handbook of Stylistics. London, New York, Routledge, pp. 471-485.

- Pignagnoli V., 2016. Sincerity, Sharing, and Authorial Discourses on the Fiction / Nonfiction Distinction: The Case of Dave Eggerss You Shall Know Our Velocity. The Poetics of Genre in the Contemporary Novel, no. 1, pp. 97-111.

- Ryan M.-L., 2019. “Truth of Fiction Versus Truth in Fiction”. Between, vol. 9, no. 18. DOI: https://doi.org/10.13125/2039-6597/3843

- Schmetkamp S., Vendrell Ferran Í., 2020. Introduction: Empathy, Fiction, and Imagination. Topoi, vol. 39, pp. 743-749. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-019-09664-3

- Vermeulen T., van den Akker R., 2010. Notes on Metamodernism. Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, vol. 2, no. 1. DOI: 10.3402/jac.v2i0.5677

- Walton K., 1990. Mimesis as Make-Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts. Cambridge, Harvard University Press. 450 p.