The Effectiveness of the TaRL Approach on Moroccan Pupils’ Mathematics, Arabic, and French Reading Competencies

Автор: Abdessamad Binaoui, Mohammed Moubtassime, Latifa Belfakir

Журнал: International Journal of Education and Management Engineering @ijeme

Статья в выпуске: 3 vol.13, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Teaching at the Right Level (henceforth, TaRL) is a new trending remedial educational approach being piloted in many countries. It basically matches pedagogical content to pupils’ educational needs through various adapted activities after segmentation of pupils’ depending on their actual difficulties and needs. In this respect, Morocco has been piloting this relatively new approach during the beginning of the school year 2022-23. Therefore, this study aimed at measuring the effectiveness of the TaRL approach on Moroccan pupils’ mathematics, Arabic, and French reading competencies. An experimental study took place involving 106 pupils from 4th grade to 6th grade during a one-month remedial course (half an hour per day, one subject per day) based on TaRL guidelines. After carefully examining the data through the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test by comparing the baseline and endline results in all three subjects. The results showed statistically high improvements with large effect sizes in the levels of the three subjects suggesting that TaRL was effective in raising the levels of numeracy and literacy and may be, safely, further adopted throughout Moroccan primary schools.

Teaching at the right level, TaRL, remedial education, Arithmetic competency, reading competency, literacy, numeracy

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/15018658

IDR: 15018658 | DOI: 10.5815/ijeme.2023.03.01

Текст научной статьи The Effectiveness of the TaRL Approach on Moroccan Pupils’ Mathematics, Arabic, and French Reading Competencies

In a recent meeting, the Moroccan Minister of National Education, declared that more than 80% of the 5th grade pupils were not able to perform arithmetic operations while stressing that a significant percentage of pupils are lagging four years behind their peers at the same level [1]. Additionally, a large proportion of Moroccan pupils does not master reading even in advanced levels as shown in the latest Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) [2, 3]. These issues have led the Moroccan Ministry of National Education (MMNE) to look for new methods to enhance the pupils’ levels in basic competencies, at least. The recent adopted approach was teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) approach. The initial evaluation of TaRL pilot project during the works of the national conference on the results of the first phase of the educational TaRL project reviewed the process of implementing TaRL approach in the Moroccan context, the preliminary results of its experimentation, and the phases to be implemented. It, also, examined the experimental results, and the requirements for the success of this approach by adopting successful training for the benefit of teachers including both theoretical aspects and field practice within classrooms targeting all the skills associated with TaRL, through drafting pre-experiment exams, correcting learners’ outputs, analyzing results and evaluating learners' levels, planning and drafting consolidation activities and evaluating their results[4].

This innovative program, which has proven its effectiveness in consolidating learners' acquisitions and reducing the differences between them, has been launched back in April 2022, as an implementation of the "road map" 20222026, making "the pupil" and "the teacher" the center of educational processes [4]. It, also, aimed at addressing the learning difficulties at the primary level in reading and arithmetic and enabling pupils to acquire basic knowledge in "mathematics, Arabic, and French languages" through unique activities that adopt the principles of interaction and pedagogical games while strengthening the human relationship between the learner and his teacher. More than 15,000 pupils have benefited from this program throughout 200 educational institutions in rural and semi-urban areas during the first three weeks of the scholar year 2022-2023, after having trained 51 educational advisors in order to follow-up with the project and 600 teachers. The next phase of the program will target 100,000 and 6,000 teachers [4].

TaRL has been developed by Pratham, an Indian non-profit organization, following observations of the existence of “left-behind” pupils who, despite their advanced school grade, still experience difficulties in basic competencies such as reading and arithmetic [5]. It aims at helping children in grades 3, 4 and 5 to ‘‘catch up” and still have “a meaningful chance at completing primary school adequately” [4]. The approach evolved from a randomized control trial program called Balsakhi (meaning child’s friend) which is a ‘‘pull-out” class during school hours focusing on basic reading and arithmetic skills conducted between 2001 and 2004. Its results showed substantial improvements in terms of basic literacy [5].

In order to put this approach to the test in the Moroccan context, we conducted an experimental study at the beginning of the school year 2022/2023 targeting a pre-selected sample of pupils with challenges in reading French, Arabic, and arithmetic based on three pre-tests targeting each competency, separately. This study would, then, attempt to answer the following research questions:

1) To which extent is the TaRL approach effective in enhancing the arithmetic skill?

2) To which extent is the TaRL approach effective in enhancing Arabic reading?

3) To which extent is the TaRL approach effective in enhancing French reading?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tarl Approach

Through answering these questions, we hope to test whether TaRL is, indeed, effective in leveling up literacy levels in terms of Arabic and French as well as numeracy in the Moroccan context. We, also, aim to verify whether the results of our study align with the results of the official study that has been carried by the MMNE claiming that TaRL was effective on a regional-scale level in fulfilling its sought goals as a remedial procedure and that it should be spread in all schools nation-wide.

Surveys in Pakistan, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Ghana showed that pupils perform significantly below competency standards for core subjects [6] as well as in Zambia [7]. Morocco is no different, annual reports show that pupils lack necessary competencies despite being in advanced grades and increasing enrolment rates. This issue is often due to mandatory success rates imposed by, sometimes, lack of infrastructure, staff shortage, staff pedagogical insufficient training, or combined classes, among other issues. Furthermore, students in Morocco scored lower than average in reading, mathematics and science according to the latest PISA study (program for international student assessment)[8]. These issues increase the number of “fallen-behind” pupils which in turn calls for state interventions. The newest reforms conducted by the Moroccan Ministry of Education (MME) included daily ordinary activities (dedicating 10 minutes every day for fun reading, 10 minutes for basic arithmetic operations, and 20 minutes of light physical movements), life activities targeting daily issues that may be encountered by learners in their daily lives outside schools settings (e.g., financial education), the syllabary reading approach [9], inclusive education, and TaRL.

TaRL is also known as Combined Activities for Maximized Learning developed by Pratham. Ref. [10] associated it with inclusive learning. Another trait related to TaRL is that it makes education a collective responsibility shared between citizens, communities, governments and school systems [11] as interventions work to bring these stakeholders together to view education as a collective responsibility that requires collective solutions. This makes sense since TaRL was developed and carried out by an NGO and volunteer teachers. TaRL segmentation of pupils is carried out by ability rather than by age and grade (cross-grade segmentation). Children are, then, taught using level-appropriate participatory teaching, learning activities, and materials [6, 10]. This pedagogy emerged from “Pratham’s own intensive experience, internal assessments, as well as external randomized evaluations”[6]. Furthermore, Ref. [7] defined it as “a form of remedial teaching” and mentioned “regular testing” as a key component to this approach. Since its emergence, TaRL was used not only in India but is being explored in several countries of sub-Saharan Africa as well as in Morocco. Bihar government, in India, conducted TaRL camps in the summer of 2008 in which teachers worked for one month exclusively on building basic reading and arithmetic skills of students in grades 3 to 5. The first finding was that the one-month camp contributed to significant learning gains and proved that even a short activity duration can be effective in building foundational skills. The second finding is that the learning gains from the one-month camp were greater than what the children acquired during the whole school year because the actual curriculum was harder and advanced for the participant students. The third finding was that pupils whose learning levels had increased during the summer camp continued to maintain their lead over those in the control group for at least two years [5]. Ref. [5], also, mentioned another intervention in the government schools of the state of Haryana in 2012/2013 using the TaRL approach which showed that schools using the Pratham method had a large and statistically significant effect on students’ reading scores. A previous study in the state of Uttar Pradesh (Banerjee et al., 2010) showed that, when implemented with carefully monitored but lightly trained community volunteers, the program improved the reading ability of participants significantly [6]. In Pakistan, 20,800 pupils across 530 schools in three provinces of Pakistan were exposed to a 45-60 days learning camp where they received remedial education based on TaRL. The results yielded positive impacts on Urdu, English, and Math learnings [12]. Back in 2016, Zambia, as well, piloted the TaRL approach in 80 schools, the positive results of the said approach resulted in involving 1800 schools afterwards [7]. Ref. [13] stated that until 2019, TaRL is being piloted in 12 countries: “À ce jour, des programmes inspirés de TaRL se déroulent dans douze pays d’Afrique, avec différents niveaux de soutien de la part des équipes de Pratham et de J-PAL.”. Fig. 1 shows the TaRL process [14].

Fig. 1. TaRL process

In Ghana, Ref. [15] explored the financial benefit of TaRL versus school feeding. They found that TaRL is likely a more efficient use of resources than school feeding. One variation of TaRL targeted at all children returns 8 Ghanaian cedis for every Ghanaian cedi spent, and another variation targeted at weaker students returns 6 Ghanaian cedis for every Ghanaian cedi spent. Also, Ref. [10,16] reviewed the success of TaRL in Indonesia which yielded positive results as well.

It is worth noting that TaRL ability groups help to ensure equitable education for all by providing resources for students who did not develop foundational skills in the early grades and are at a higher risk of dropping out. Importantly, learners' ability grouping can vary by subject-for example, low in numeracy, high in literacy—avoiding the social stigma that is frequently associated with ability grouping [7]. In order to avoid such social stigma, we have made it clear to children that it would be a grouping for a limited time followed by normal grouping for normal classes every day.

In the same respect, TaRL is known in Bangladesh as the Kumon Method [17]. The experimenters of this method measured the improvement of cognitive abilities of students using pre-test and post-test mathematics test scores and catch-up effects in terms of noncognitive abilities or personality traits measured through a self-esteem scale. What distinguishes this study is the fact that they used time reduction as well as time-adjusted test score and it took 20 months of follow-up. They found a reasonable longer-term impact on cognitive abilities for younger students and that the estimates indicate that the program’s benefits exceed its costs which is the same observation as in Ghana[15]. Finally, after studying the tension between curriculum coverage and quality learning from the experiences of South African teachers, [18] concluded by recommending using TaRL to resolve this sort of tension.

In the Moroccan context, the three-week trial conducted at the beginning of 2022/2023 academic year was announced to be successful. However, neither statistics nor the methodology is not yet published. That is may be to the fact that the program is still ongoing and will be spread as in the case of Nepal [19]. Thus, we will investigate the impact of this method on Moroccan pupils’ numeracy and literacy skills following rigorous scientific measures on a smaller-scale study.

3. Method

In India, learners were assessed through the Annual Status of Education Report test, which classifies children into groups. In terms of reading, the following categories apply: (1) a beginner (cannot recognize letters), (2) letter recognition, (3) word recognition, (4) simple paragraph reading, and (5) story reading. Reading Level takes on five different values, that is, 0 – cannot read, 1 – can read letters, 2 – can read words, 3 – can read a paragraph, and 4 – can read a story [20]. With respect to math, categories include (1) beginner (cannot recognize numbers), (2) one-digit number recognition 1-9, (3) two-digit number recognition 10-99, (4) subtraction level, and (5) division level. In Indonesia, they used five levels in mathematics pre-assessments, namely: beginner level, single-digit level, double-digit level, three-digit level, and four-digit level[10]. Similarly, the variable Math level takes on four different values, that is, 0 – cannot recognize numbers, 1 – recognizes numbers, 2 – can perform subtraction operations, and 3 – can perform division operations [20]. In Morocco, they used, in terms of French and Arabic reading, 1-beginner, 2- letter level, 3-word level, 4-paragraph level, 5-story level, 6-comprehesion level. For math, Moroccan teachers relied on the same categories as in the Indian model [21].

For the sake of this study, we will be relying on four levels in terms of reading: 0-beginner (value=0), 1-syllable level (value=1), word-level (value=2), sentence level (value=3), and paragraph level (value=4). Concerning mathematics, we will be relying on the following categories: 0- beginner (value=0), 1-addition level (value=1), subtraction-level (value=2), multiplication-level (value=3), and division- level (value=4). First, we conducted a pre-test in order to assign pupils to their respective categories, then, we assigned each pupil category to a teacher. Afterwards, we conducted a post-test with the same objectives of the pre-test. Concerning data analysis, the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test will be performed in order to evaluate if there are any improvements in the sample’s level of mathematics, Arabic and French reading. The Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test is a non-parametric alternative test to the t-test (since the data is not normally distributed).

In order to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the results, the school where the experiment took place was randomly chosen. The classes were, also, randomly chosen. The teachers were the same teachers that, regularly, taught the classes. The tests were corrected by different teachers each time.

4. Results and Discussion 4.1. Pre-intervention Results

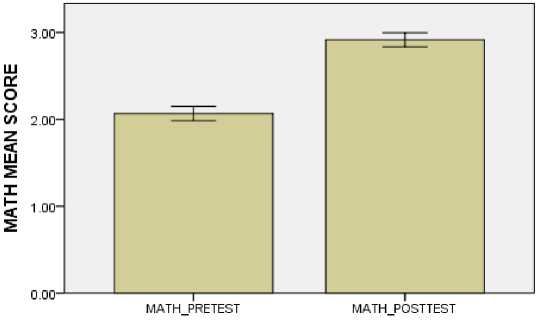

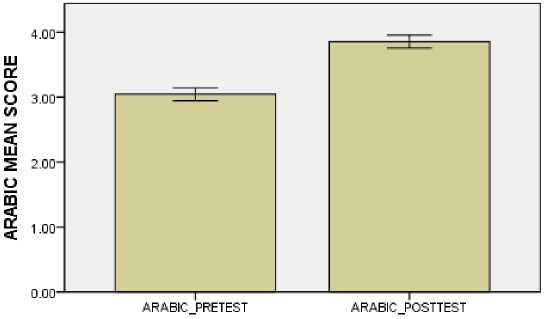

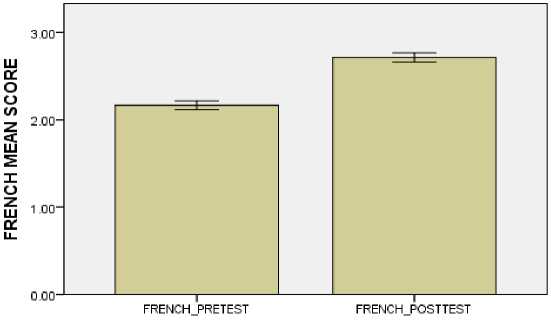

Since the data is abnormally distributed (Kolmogorov-Smirnov=.000, Shapiro-Wilk=.000, see Table 9), the Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was carried out in order to evaluate whether there were any changes in the sample’s level of mathematics, Arabic and French reading (Table 11). The test for mathematics improvement revealed a statistically significant positive change in the level following the one-month course, Z= -7.152760, p=.000, with a large effect size (r=.69). Also, the test for Arabic reading improvement revealed a statistically significant positive change in the level following the one-month course, Z=-6.271967, p=.000, with a large effect size (r=.60). Finally, the test for French reading improvement revealed a statistically significant positive change in the level following the one-month course, Z= -7.361956, p=.000, with a large effect size (r=.71). In addition, according to Table 10., 63 (i.e., 60%) pupils have improved (positive ranks), 43 (i.e., 40%) maintained their level, while 0 pupils have not improved in mathematics. Concerning Arabic, 50 (i.e., 47%) pupils have improved (positive ranks), 56 (i.e., 53%) maintained their level, while 0 pupils have not improved. Finally, for French reading, 56 (i.e., 53%) pupils have improved (positive ranks), 50 i.e., 47%) maintained their level, while 0 pupils have not improved. Accordingly, we can infer from Table. 1, Table. 5, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, and Fig. 4 that there have been substantial improvements in the mean scores. Table. 2, Table. 3, Table. 4, Table. 6, Table. 7, and Table. 8 show frequency differences between the pre-tests and post-tests.

Table 1. Pre-test descriptive statistics

|

Math Pretest |

Arabic reading Pretest |

French reading Pretest |

||

|

N |

Valid |

106 |

106 |

106 |

|

Missing |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Mean |

2.07 |

3.05 |

2.17 |

|

|

Median |

2.00 |

4.00 |

3.00 |

|

|

Mode |

2 |

4 |

3 |

|

|

Std. Deviation |

1.157 |

1.190 |

1.397 |

|

Table 2. Mathematics’ pretest frequencies

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Beginner |

17 |

16.0 |

16.0 |

16.0 |

|

Addition level |

3 |

2.8 |

2.8 |

18.9 |

|

|

Subtraction level |

55 |

51.9 |

51.9 |

70.8 |

|

|

Multiplication level |

18 |

17.0 |

17.0 |

87.7 |

|

|

Division level |

13 |

12.3 |

12.3 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

106 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

Table 3. Arabic reading pretest frequencies

|

Arabic reading Pretest |

|||||

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Cannot read |

4 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

|

Can read syllables |

11 |

10.4 |

10.4 |

14.2 |

|

|

Can read words |

15 |

14.2 |

14.2 |

28.3 |

|

|

Can read sentences |

22 |

20.8 |

20.8 |

49.1 |

|

|

Can read paragraphs |

54 |

50.9 |

50.9 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

106 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

Table 4. French reading pretest frequencies

|

French reading Pretest |

|||||

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Cannot read |

17 |

16.0 |

16.0 |

16.0 |

|

Can read syllables |

23 |

21.7 |

21.7 |

37.7 |

|

|

Can read words |

12 |

11.3 |

11.3 |

49.1 |

|

|

Can read sentences |

33 |

31.1 |

31.1 |

80.2 |

|

|

Can read paragraphs |

21 |

19.8 |

19.8 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

106 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

Table 5. Post-test descriptive statistics

|

Math Post-test |

Arabic reading Post-test |

French reading Post-test |

||

|

N |

Valid |

106 |

106 |

106 |

|

Missing |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Mean |

2.92 |

3.86 |

2.72 |

|

|

Median |

3.00 |

4.00 |

4.00 |

|

|

Mode |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

|

Std. Deviation |

1.105 |

.654 |

1.485 |

|

Table 6. Mathematics’ Post-test frequencies

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Beginner |

5 |

4.7 |

4.7 |

4.7 |

|

Addition level |

5 |

4.7 |

4.7 |

9.4 |

|

|

Subtraction level |

24 |

22.6 |

22.6 |

32.1 |

|

|

Multiplication level |

32 |

30.2 |

30.2 |

62.3 |

|

|

Division level |

40 |

37.7 |

37.7 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

106 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

Table 7. Arabic Post-test frequencies

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Cannot read |

2 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

|

Can read syllables |

1 |

.9 |

.9 |

2.8 |

|

|

Can read words |

1 |

.9 |

.9 |

3.8 |

|

|

Can read sentences |

2 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

5.7 |

|

|

Can read paragraphs |

100 |

94.3 |

94.3 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

106 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

Table 8. French Post-test frequencies

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

||

|

Valid |

Cannot read |

12 |

11.3 |

11.3 |

11.3 |

|

Can read syllables |

15 |

14.2 |

14.2 |

25.5 |

|

|

Can read words |

18 |

17.0 |

17.0 |

42.5 |

|

|

Can read sentences |

7 |

6.6 |

6.6 |

49.1 |

|

|

Can read paragraphs |

54 |

50.9 |

50.9 |

100.0 |

|

|

Total |

106 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

||

Table 9. Tests of normality

Table 10. Ranks’ statistics

|

N |

Mean Rank |

Sum of Ranks |

||

|

Math post-test - Math pre-test |

Negative Ranks |

0a |

.00 |

.00 |

|

Positive Ranks |

63b |

32.00 |

2016.00 |

|

|

Ties |

43c |

|||

|

Total |

106 |

|||

|

Arabic reading post-test - Arabic reading pre-test |

Negative Ranks |

0d |

.00 |

.00 |

|

Positive Ranks |

50e |

25.50 |

1275.00 |

|

|

Ties |

56f |

|||

|

Total |

106 |

|||

|

French reading post-test - French reading pre-test |

Negative Ranks |

0g |

.00 |

.00 |

|

Positive Ranks |

56h |

28.50 |

1596.00 |

|

|

Ties |

50i |

|||

|

Total |

106 |

|||

-

a. Math post-test < Math pre-test

-

b. Math post-test > Math pre-test

-

c. Math post-test = Math pre-test

-

d. Arabic reading post-test < Arabic reading pre-test e. Arabic reading post-test > Arabic reading pre-test f. Arabic reading post-test = Arabic reading pre-test g. French reading post-test < French reading pre-test h. French reading post-test > French reading pre-test i. French reading post-test = French reading pre-test

Table 11. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test

TESTS

Error Bars: 95% Cl

-

Fi g. 2. Mathematics’ mean scores’ bars’ graph

TESTS

Error Bars: 95% Cl

-

Fi g. 3. Arabic mean scores’ bars’ graph

TESTS

Error Bars: 95% Cl

Fi g. 4. French mean scores’ bars’ graph

5. Conclusion

After careful evaluation of the study described in this article, we can confidently say that the official reports of the national study were correct and that TaRL is indeed effective in the Moroccan context. The following are some remarks generated during the process. First, we noticed that the pupils in level three could easily move to level four in the three subjects as they needed only knowledge refining through TaRL; Second, having been taught by different teachers and with mixed-levels’ pupils within the various TaRL classes had positive impacts in terms of triggering pupils’ attention through the unique teaching style of each teacher; Third, TaRL classes were homogeneous in terms of learning difficulties which was something teachers had praised; however, teachers pointed out that there are specific needs’ groups even after the right level categorization (for instance, pupils with same decoding difficulties); Fourth, assigning homework following TaRL sessions helped pupils in keeping up with the courses as the majority of the came ready to the following classes. Also, when pupils had shown signs of improvement, they were promoted to the next group which was motivating for them.

The limitations related to our experiment were the lack of teaching aids (one laptop and one data show device, plus few educational tools), overlapping classes, and teaching after official courses which made pupils a little bit exhausted. In addition, absenteeism hindered the progress of the support for absent pupils. However, absent pupils missed a session each which mitigated the impact of this phenomenon. Arabic classes were stopped after two weeks because of the positive results pupils had made except for two special cases who had dyslexia. We attribute this positive impact to the fact that Arabic is the mother tongue of the participant sample.

In Morocco and within the framework of implementing the requirements of the road map, especially those related to the learner and the need to improve the quality of learning and ensure the provision of appropriate remedial education to raise the level of public-school outputs in terms of basic learning in addition to the results of the reports included in the national program assessing the achievements of the 2019 scholar year, which highlighted a huge decline in the level of achievement at the end of the primary cycle taking into consideration the recommendations of the World Bank's report on the low levels of performance of Moroccan learners, which recorded alarming percentages up from 66 percent of Moroccan pupils who have reached the end of the primary cycle while not mastering basic reading competencies which makes them prone to dropping out of schools, in addition to the negative consequences of suspending in-person teaching as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, experimenting TaRL at the primary level aimed at targeting the most effective ways to address the accumulated difficulties in basic learning, especially those related to Arabic, French and mathematics and supporting the abilities of those involved in the educational process to contribute to raising the quality of educational productivity of primary educational institutions [4]. The following objectives were targeted: (1) increasing the competencies of educational actors in the areas of academic support; (2) addressing the school failures according to levels of need; (3) studying the feasibility of adopting TaRL in resolving difficulties and exploring ways to expand its scope. It is worth noting that national-scale experiment in Morocco included all regional academies of education during the pilot project. The sample involved: 52 educational actors following up TaRL approach testing, 250 schools, 550 teachers and facilitators of TaRL Approach activities, 600 teachers as additional TaRL testers, 11,000 male and female learners benefiting from TaRL remedial approach. The experiment duration took place from 06 September 2022 to 30 December 2022[4].

This study concludes that TaRL is effective as a remedial procedure especially in Arabic as it is the native language in Morocco. It was effective, as much, in the arithmetic even though the one-month camp was not long enough for the zero and one categories to reach the fourth category level (they weren’t taught the division technique). For the French language, we may say that mostly pupils who had some basic literacy were able to move up the ladder (categories two and three) while the lower categories still experienced difficulties. This is may be due to the fact that French is the second learning language and most Moroccan pupils and students keep experiencing difficulties learning the language even in high schools and universities.

Furthermore, over 60 million students in India and Africa have benefited from reorienting instruction based on TaRL [22]. In the same respect, TaRL was found to be effective as a remedial education process against Covid 19 negative learning consequences [23] as it was found to be helpful in many other contexts. However, special cases with mental disabilities and learning difficulties still need help in terms of remedial education. We recommend that other studies should focus on those categories as we wish to see whether TaRL is effective in English language remedial education in the Moroccan context. Further information about the TaRL implementation teams, assessment, classroom methodology, measurement and monitoring, and its different models were discussed in [24].

Finally, this paper should constitute an insightful source about TaRL effects on Arabic and on French as particular cases in an African-Arab country such as Morocco. Such studies should be taken into account in order to avoid over-ambitious curricula as discussed in [25] and address the educational ecosystem problems of each country objectively so as to avoid many problems among which the inequalities in learning provision within the same state. The results of the study are, also, insightful for the other Arab countries wishing to adopt TaRL as well as for countries teaching French as a second language. This study taps into the multitude of remedial approaches in the field of education which constitute an integral part to the teaching process.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank teachers Yassine Echcharyfy and Adnane Abdaoui for their contributions in the remedial teaching sessions.

Список литературы The Effectiveness of the TaRL Approach on Moroccan Pupils’ Mathematics, Arabic, and French Reading Competencies

- A. Chrid, “Benmoussa: A large percentage of primary school students do not master arithmetic operations - Al Jarida 24,” Oct. 2022. https://aljarida24.ma/p/actualites/210611/ (accessed Oct. 18, 2022).

- International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, “Pirls 2016 International Results in Reading. TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center.” Lynch School of Education, Boston College and International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA), 2017. [Online]. Available: http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/pirls2016/international-results/wp-content/uploads/structure/CompletePDF/P16-PIRLS-International-Results-in-Reading.pdf

- A. Binaoui, M. Moubtassime, and L. Belfakir, “The Effectiveness and Impact of Teaching Coding through Scratch on Moroccan Pupils’ Competencies,” International Journal of Modern Education and Computer Science, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 44–55, 2022, doi: 10.5815/ijmecs.2022.05.05.

- Moroccan Ministry of Education, “Initial evaluation of the pilot project ‘Teaching at the Right Level,’” Oct. 2022. Accessed: Oct. 17, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.men.gov.ma/Ar/Pages/DetailActualite.aspx?ActuID=kITPBmXUCss=

- R. Banerji and M. Chavan, “A twenty-year partnership of practice and research: The Nobel laureates and Pratham in India,” World Development, vol. 127, p. 104788, Mar. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104788.

- A. Banerjee et al., “Mainstreaming an effective intervention: Evidence from randomized evaluations of ‘Teaching at the Right Level’ in India,” National Bureau of Economic Research, 2016.

- N. Vromant, L. Kuppens, M. Hazemba, F. K. Mwamba, and E. Cupito, “Scaling Teaching at the Right Level,” Ensuring All Children Learn: Lessons from the South on What Works in Equity and Inclusion, p. 101, 2021.

- OECD, PISA 2018 Assessment and Analytical Framework. OECD, 2019. doi: 10.1787/b25efab8-en.

- Abdessamad Binaoui, M. Moubtassime, and L. Belfakir, “The Impact and Effectiveness of the Syllable-based Reading Approach on Moroccan Pupils’ Reading Competency,” (unpublished).

- A. Widodo and D. Indraswati, “HOW TO DESIGN INCLUSIVE LITERACY AND NUMERACY LEARNING IN ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS?,” Jurnal Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Missio, vol. 14, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Aug. 2022, doi: 10.36928/jpkm.v14i2.1134.

- B. Alcott, P. Rose, R. Sabates, and M. Cherfils, “Experience and lessons of learning intervention programmes across the PAL Network members,” (REAL Centre Research and Policy Paper 18/4). Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK. (2018), Dec. 2018. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1994919 (accessed Oct. 26, 2022).

- “Ins and outs of rolling out Teaching at the Right Level (TaRl) in Pakistan | Unesco IIEP Learning Portal.” https://learningportal.iiep.unesco.org/en/library/ins-and-outs-of-rolling-out-teaching-at-the-right-level-tarl-in-pakistan (accessed Oct. 24, 2022).

- S. Lakhsman, “Améliorer les résultats en lecture et en arithmétique à grande échelle : « Enseigner au bon niveau » (Teaching At The Right Level), l’approche de Pratham,” Revue internationale d’éducation de Sèvres, Jun. 2019, doi: 10.4000/ries.7442.

- W. C. Ngeno, V. Ngindiru, and A. Ali, “Adaptation of solutions from South Asia: Experiences of improving learning outcomes”.

- F. E. Turkson, P. T. Baffour, and B. Wong, “Cost-benefit analysis of interventions to improve learning in Ghanaian schools: A comparison between school feeding and teaching at the right level: Ghana Priorities,” Ghana Priorities, Copenhagen Consensus Center, 2020.

- A. Widodo and U. Umar, “Analysis of Literacy Program Based on Ability Level of Students in Elementary School,” 1, vol. 10, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Aug. 2021, doi: 10.35337/scientia.Vol10.pp71-76.

- Y. Sawada, M. Mahmud, M. Seki, and H. Kawarazaki, “Fighting the Learning Crisis in Developing Countries: A Randomized Experiment of Self-Learning at the Right Level.” Rochester, NY, Jun. 13, 2022. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3471021.

- C. A. Bertram, C. C. N. Mthiyane, and J. Naidoo, “The tension between curriculum coverage and quality learning: The experiences of South African teachers,” International Journal of Educational Development, vol. 81, p. 102353, Mar. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102353.

- K. Radhakrishnan, U. Sharma, and A. R. Shinde, “Phone-Based Assessment : Experience from Nepal (English),” Aug. 2022, Accessed: Oct. 25, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2653224/phone-based-assessment/3676145/

- R. Handa, “A Lesson in Learning: Improving Learning Outcomes in India Via Pedagogical Innovation,” Scripps Senior Theses, Jan. 2018, [Online]. Available: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1105

- Moroccan Ministry of Education, “دليل أجرأة الدعم المؤسساتي وفق مقاربة TaRL. مرحلة التجريب، TaRl implementation guide.” 2022. [Online]. Available: shorturl.at/jsE45

- “Teaching at the Right Level to improve learning,” The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL). https://www.povertyactionlab.org/case-study/teaching-right-level-improve-learning (accessed Jan. 21, 2023).

- M. Kaffenberger, “Modelling the long-run learning impact of the Covid-19 learning shock: Actions to (more than) mitigate loss,” International Journal of Educational Development, vol. 81, p. 102326, Mar. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2020.102326.

- “The TaRL Approach,” Teaching at the Right Level. https://www.teachingattherightlevel.org/the-tarl-approach/ (accessed Jan. 21, 2023).

- L. Pritchett and A. Beatty, “The Negative Consequences of Overambitious Curricula in Developing Countries.” Rochester, NY, Dec. 28, 2012. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2195509.