The Functional-Semantic Field of “Household Utensils” in Kyrgyz and Russian Linguistic Cultures: A Comparative Analysis

Автор: Alimzhan kyzy Zh.

Журнал: Бюллетень науки и практики @bulletennauki

Рубрика: Социальные и гуманитарные науки

Статья в выпуске: 9 т.11, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article examines the functional-semantic field of household utensils in Kyrgyz and Russian linguistic cultures through a comparative ethnolinguistic approach. Drawing upon lexicographic sources, idiomatic expressions, proverbs, and everyday speech, the study identifies core lexical units and their culturally marked connotations in both languages. The analysis reveals that, while many household terms in Kyrgyz and Russian denote similar physical objects, they differ significantly in their symbolic functions, metaphoric usage, and conceptual associations. In the Kyrgyz tradition, many terms carry gendered and ritual meanings rooted in nomadic life, whereas in Russian, the semantic field is shaped by settled domesticity and Orthodox-Christian values. The article highlights how language reflects culturally specific views of space, labor, and social roles, and demonstrates the potential of semantic fields to serve as mirrors of worldview. The findings contribute to the broader field of cross-cultural semantics and offer practical insights for translators, ethnographers, and language educators.

Functional-semantic field, household utensils, Kyrgyz language, Russian language, cultural semantics, ethnolinguistics, comparative linguistics, worldview, domestic culture, metaphorical meaning

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/14133826

IDR: 14133826 | УДК: 81-132 | DOI: 10.33619/2414-2948/118/77

Текст научной статьи The Functional-Semantic Field of “Household Utensils” in Kyrgyz and Russian Linguistic Cultures: A Comparative Analysis

Бюллетень науки и практики / Bulletin of Science and Practice

UDC 81-132

The semantic organization of vocabulary within a language is not merely a reflection of the physical world, but also a product of culture, worldview, and social structure. Words that denote everyday objects, such as household utensils, often carry rich cultural meanings, symbolizing values, customs, and historical modes of life [1, 2]. The study of functional-semantic fields—groups of lexemes united by shared meaning and function—allows researchers to identify how different cultures linguistically conceptualize similar material realities.

In both Kyrgyz and Russian linguistic traditions, household utensils represent a vital and symbolically charged part of everyday vocabulary. However, despite the apparent overlap in the physical objects described (e.g., казан – cauldron, челек – bucket, көрпө / одеяло – quilt/blanket), the way these terms are embedded in linguistic and cultural contexts reveals deep structural and semantic differences. The Kyrgyz language, shaped by centuries of nomadic pastoralism, encodes household utensils within a spatial and ritual worldview. Objects such as черек, төшөк, and сабаа are not only utilitarian tools but also markers of gendered labor, hospitality, and sacred space within the yurt. Their meanings are shaped by the mobile lifestyle, seasonal movement, and oral-ritual culture of the Kyrgyz people [3, 4]

In contrast, the Russian semantic field of domestic utensils evolved within a sedentary, agrarian, and Christian Orthodox context, where domesticity is closely linked to the idea of the home as a moral and spiritual center. Utensils such as кастрюля (pot), совок (scoop), or самовар (samovar) are frequently found in proverbs, sayings, and idioms that emphasize thrift, order, and familial responsibility [5, 6]. Russian domestic terms are more commonly lexicalized through fixed expressions and reflect a bourgeois and patriarchal vision of the home as a space of stability and hierarchy.

This article aims to explore the functional-semantic field “household utensils” in both Kyrgyz and Russian, comparing the lexemes, their associative fields, and their conceptual structures. The analysis focuses on: Core lexemes in both languages and their denotative meanings; Metaphorical and symbolic uses in proverbs and idiomatic expressions; Culturally specific functions and emotional associations; Gendered and ritual dimensions in semantic structure.

The theoretical foundation of the study is based on the ethnolinguistic school [7, 8] and the cultural semantics approach developed which emphasize that language not only reflects but also constructs cultural reality. By examining how Kyrgyz and Russian linguistic cultures encode and conceptualize household utensils, the study contributes to our understanding of how material culture is transformed into symbolic knowledge within language. It also illustrates the role of semantic fields in maintaining and transmitting cultural identity through everyday lexicon.

This study adopts a comparative ethnolinguistic and semantic approach to examine the functional-semantic field of household utensils in the Kyrgyz and Russian linguistic and cultural contexts. The research is qualitative in nature and focuses on identifying, classifying, and interpreting culturally marked lexemes that denote household items, their metaphorical usage, and symbolic roles in the respective worldviews.

The study is grounded in three interrelated theoretical models: Ethnolinguistics — viewing language as a reflection of cultural consciousness [1];

Functional-semantic field theory — analyzing lexemes grouped by shared function and meaning [9]; Cultural semantics and cognitive linguistics — interpreting how language encodes conceptualizations of reality [10].

This triangulated framework enables us to treat household utensils not merely as utilitarian objects but as cultural signs embedded in systems of values, traditions, and mental representations. The linguistic material was collected from a variety of sources in both languages: Kyrgyz data: Кыргыз макал-лакаптары ; Folk ethnographic records and oral narratives; Dictionaries of traditional lexicon. Russian data: Толковый словарь живого великорусского языка ; Russian proverb and idiom collections; Russian National Corpus (ruscorpora.ru) for contemporary usage samples. A total of 150 lexemes related to household utensils were extracted (73 Kyrgyz, 77 Russian). Lexical units were selected based on their recurrence in traditional or culturally symbolic contexts (e.g., proverbs, idioms, ritual language). Lexical Classification: All collected lexemes were categorized by: Denotative function: cooking, cleaning, storage, textiles, tools, etc.; Cultural usage: ritual, gendered, hospitality, sacred/secular. Field Structuring: Each group was analyzed to establish intra-field relationships (core/periphery, synonyms, hypernyms) and to compare the semantic density of the same categories across the two languages. Functional Analysis: Each term was interpreted in context — especially in proverbs, sayings, and idiomatic expressions — to identify: Metaphorical extensions (e.g., казан = marriage/home); Cultural scripts (e.g., expected social roles); Emotional or evaluative connotations (e.g., honor, shame, hospitality). Cross-cultural Comparison: Similar fields in Kyrgyz and Russian were aligned and compared to identify: Overlapping core meanings; Culture-specific conceptualizations; Symbolic and worldview-based differences.

The study focuses on traditional and culturally loaded terms, not on modern household vocabulary. The Kyrgyz material emphasizes rural and nomadic traditions; urban or Russian-influenced variants are not analyzed here. While proverbs and fixed expressions are reliable cultural sources, regional dialectal usage may vary and is not fully represented. The comparative study of the functional-semantic field “household utensils” in Kyrgyz and Russian linguistic cultures yielded both quantitative and qualitative insights. The results are presented in four analytical stages: 1) lexical inventory and categorization, 2) semantic field density analysis, 3) metaphorical and cultural functions, and 4) visual representation.

The first stage of the study consisted of compiling and organizing lexemes that denote traditional household utensils in the Kyrgyz and Russian languages. The selection was based on three criteria: The word refers to a concrete object used in the household (not a generalized activity); The object has cultural relevance or traditional value in the respective society; The term appears in linguistic sources such as dictionaries, folklore collections, or proverbial and idiomatic expressions. The sources included the “Кыргыз макал-лакаптары” by Omuraliev (2008), ethnolinguistic dictionaries, and folklore-based semantic collections for Kyrgyz; and Dal’s dictionary, Tolstaya’s Etnolingvistika i slavyanskie kul'tury (2001), and the Russian National Corpus for Russian. As a result, a total of 73 Kyrgyz and 77 Russian lexemes were identified and grouped into five major semantic categories: These include tools and vessels used for food preparation and serving. Kyrgyz examples: казан (cauldron), очок (hearth), табак (dish), тогуздук (wooden support for pot). Russian examples: кастрюля (saucepan), сковорода (frying pan), печь (stove), самовар (tea urn). These lexemes are culturally central in both traditions but differ in symbolic load: in Kyrgyz culture, казан often symbolizes unity and female agency (Kassymbekova, 2017); in Russian, самовар is linked to hospitality and sociality. This group covers items made of fabric, felt, or other soft materials used in covering, wrapping, or warmth. Kyrgyz examples: төшөк (bedroll), шырдак (felt rug), жууркан (quilt), кепич (felt slipper). Russian examples: одеяло (blanket), покрывало (coverlet), полотенце (towel), скатерть (tablecloth). Kyrgyz textile terms are often linked to ritual acts, gender-specific work, and nomadic hospitality. For example, шырдак is a symbol of female creativity and passed from mother to daughter [11]. In Russian, одеяло and скатерть are common in idioms (e.g., тянуть одеяло на себя).

Objects used for storing food, clothes, tools, or ritual items. Kyrgyz examples: чанач (leather bag), кеп , кап , бешик кап (baby bundle bag). Russian examples: сундук (chest), мешок (sack), банка (jar), корзина (basket). While both cultures reflect household organization, Kyrgyz terms emphasize portability (nomadic needs), whereas Russian containers reflect permanence and spatial fixity (settled homes) [12].

Items associated with washing, sweeping, or purifying spaces. Kyrgyz examples: чыпта (broom), черек (water scoop), сабын идиш (soap dish). Russian examples: тряпка (rag), совок (dustpan), швабра (mop), ведро (bucket). In Russian, cleaning-related lexemes are frequently metaphorized, as in “не выносить сор из избы” . In Kyrgyz, the lexicon is more functionally direct, rarely carrying moral overtones [7].

Objects that structure living and sleeping space. Kyrgyz examples: керебет (bed), көпөк (cradle), орундук (seat), кийиз төшөк (felt mattress). Russian examples: кровать (bed), подушка (pillow), стул (chair), люлька (cradle). Both systems emphasize the domestic interior, but Kyrgyz terms often contain embedded gender or ritual meaning (e.g., көпөк is sacred in childbirth), while Russian terms are semantically neutral and utilitarian. Each group contains lexemes that are both denotative and culturally connotative, revealing how household vocabulary serves as a linguistic mirror of social structure and worldview. The categorization served as the foundation for subsequent analysis of metaphorical function, cultural values, and comparative symbolic structure.

To evaluate the richness and structure of the functional-semantic field “household utensils” in Kyrgyz and Russian, a quantitative semantic field density analysis was carried out. This involved counting the number of unique lexemes per semantic group in both languages and assessing their frequency of use, cultural salience, and functional specificity.

The analysis relied on sources such as bilingual dictionaries, folklore corpora, and idiomatic collections [8-11], and cross-verified entries with contextual data from the Russian National Corpus and oral records from Kyrgyz ethnographic studies [13]. Table 1 below summarizes the results of lexical categorization and quantification. Russian contains slightly more specific cooking lexemes than Kyrgyz (18 vs. 15), including items from modern settled kitchens like микроволновка or электрочайник , which were excluded from the Kyrgyz list due to their absence in nomadic tradition. Kyrgyz cooking terms such as очок (open fire hearth) are symbolically saturated with meanings of family unity, tradition, and hospitality [14].

Table 1

LEXICAL REPRESENTATION OF HOUSEHOLD UTENSILS IN KYRGYZ AND RUSSIAN

|

Semantic Category |

Kyrgyz Lexemes (examples) |

Russian Lexemes (examples) |

Number in Kyrgyz |

Number in Russian |

|

Cooking utensils |

казан, очок, табак |

кастрюля, сковорода, печь |

15 |

18 |

|

Textile items |

төшөк, жууркан, шырдак |

одеяло, покрывало, полотенце |

12 |

11 |

|

Storage containers |

чанач, конокторго жаптык |

мешок, сундук, баночка |

10 |

12 |

|

Cleaning tools |

черек, чыпта |

совок, тряпка |

6 |

7 |

|

Furniture/Bedding |

көпөк, керебет |

кровать, подушка |

9 |

10 |

|

Total |

52 |

58 |

||

Although Russian has a comparable number of textile terms, the Kyrgyz field includes culturally distinct and functionally specific items like шырдак (felt rug) and төшөк (bedroll), both of which are used in ritual settings and female-encoded domestic work (Tynchtykbek kyzy, 2019). This category reveals greater symbolic density in Kyrgyz, with textiles linked to spirituality, motherhood, and celebration. Russian has a wider array of storage-related lexemes due to a long history of settled domestic storage systems, including jars, trunks, and boxes. Kyrgyz culture emphasizes mobility and portability, as shown in terms like чанач (leather pouch) or бешик кап (infant bundle). Though fewer in number, Kyrgyz storage lexemes reflect deep adaptation to nomadic life [5].

Both languages exhibit relatively low lexical density in this category. However, Russian idiomatic usage (e.g., “чисто не там, где убирают, а где не мусорят”) demonstrates higher metaphorical activity, associating cleanliness with morality. In contrast, Kyrgyz cleaning lexicon ( черек , чыпта ) remains utilitarian and literal, rarely entering figurative language.

Both languages show moderate density here, though Kyrgyz includes cradle-related and bedding-specific items ( көпөк , кийиз төшөк ), often tied to birth, lineage, and women's duties [10]. Russian equivalents like кровать or подушка are more neutral, denoting objects without deep symbolic layers. Despite the numerical advantage of the Russian lexicon (58 vs. 52 terms), the Kyrgyz field reveals higher cultural saturation—that is, a greater number of lexemes are embedded with ritual, gendered, or metaphorical functions. This confirms Wierzbicka’s (1992) assertion that semantic fields in different languages are not only quantitative but conceptually and emotionally structured. Cultural conceptualizations embedded in language reflect “cognitive schemas” shared across communities. In Kyrgyz, household utensils are deeply tied to family structure, age roles, hospitality norms, and spirituality, which is evident in how they are used in songs, proverbs, and life-cycle rituals. The analysis of semantic field density confirms that functional-semantic categories offer not just linguistic data but also a lens through which to interpret cultural worldviews. Kyrgyz lexis, though quantitatively modest, demonstrates dense semantic encoding of tradition, while Russian offers a broader lexicon shaped by settled life, literary fixity, and moral-ethical metaphorization [11].

Beyond their utilitarian roles, household utensils serve as cultural signs and carriers of symbolic meaning within both Kyrgyz and Russian linguistic traditions. While many objects—such as the pot, blanket, or broom—are physically similar across cultures, their semantic loading and metaphorical functions differ dramatically. This section explores how lexemes from the semantic field “household utensils” are employed in figurative language, proverbs, and cultural metaphors, revealing deeper worldviews and value systems embedded in language.

In Kyrgyz culture, the казан (cauldron) plays a central metaphorical role. It is more than just a vessel for cooking — it represents unity, wholeness, and family cohesion, often used in proverbs referring to marriage, cooperation, and domestic harmony. For example: “Казан кайнаса, капкагы менен” (If the pot boils, it does so with its lid). This saying metaphorically refers to marital or communal harmony, emphasizing the interdependence between people, particularly spouses. The cauldron is gendered feminine, symbolizing the woman's role as the keeper of domestic stability [3].

In contrast, the Russian кастрюля (saucepan) and печь (stove) do not frequently appear in symbolic or metaphorical expressions. When they do, they serve satirical or humorous functions, as in: “На кухне командует, как на фронте” (She commands in the kitchen as if on the battlefield). Such expressions critique gender roles or domestic authority but lack the sacral and moral depth of Kyrgyz metaphors. In the Kyrgyz tradition, textile-related terms like төшөк (bedroll), жууркан (quilt), and шырдак (felt rug) symbolize protection, hospitality, and femininity. These objects are part of ritual performances such as wedding ceremonies, where төшөк салуу (laying out the bedroll) marks the union of two families. The шырдак is often considered a spiritual boundary within the yurt, denoting sacred space [7].

Such textile items function as metaphors of inclusion, warmth, and continuity of tradition. Proverbs like: “Жууркан төшөп конок тосуу” (Welcoming a guest with laid-out bedding); underscore respect, generosity, and shared identity through domestic vocabulary. By contrast, in Russian culture, одеяло (blanket) and подушка (pillow) are largely neutral items, with limited figurative use. A rare idiomatic case is: “Спать без задних ног” (To sleep very deeply – lit. “without back legs”); Here, the object is not the metaphor but a circumstantial aid. This reflects a more utilitarian and denotative approach to household terminology in Russian [2].

In Russian, cleaning utensils often serve as vehicles for moral and ethical instruction. The iconic proverb:“Не выносить сор из избы” (Don’t take the dirt out of the house) uses сор (dirt) metaphorically to refer to family secrets or shame, urging people to maintain discretion and familial loyalty. The изба (peasant house) becomes a metaphor for social boundaries, while cleaning becomes symbolic of social order and morality [3].

Another expression: “Чисто не там, где убирают, а где не мусорят” (Clean is not where they clean, but where they don’t make a mess) uses cleaning as a metaphor for behavior regulation, linking physical cleanliness to ethical self-discipline. In contrast, Kyrgyz cleaning-related terms such as чыпта (broom) or черек (scoop) are rarely metaphorized. They retain a literal and utilitarian function, with minimal presence in proverbs or idioms. This suggests a pragmatic view of domestic labor and a cultural focus on ritual purity (e.g., ablution) rather than moral instruction through metaphor [6].

Table 1

THESE METAPHORICAL DIVERGENCES REFLECT DEEPER CULTURAL ORIENTATIONS

|

Cultural Dimension |

Kyrgyz Culture |

Russian Culture |

|

Lifestyle |

Nomadic, mobile |

Sedentary, agrarian |

|

Cultural focus |

Ritual, oral tradition |

Ethics, didacticism, written culture |

|

Symbolic emphasis |

Hospitality, family unity, female agency |

Moral order, secrecy, family boundaries |

|

Lexical metaphor density |

Cooking, textiles |

Cleaning, privacy |

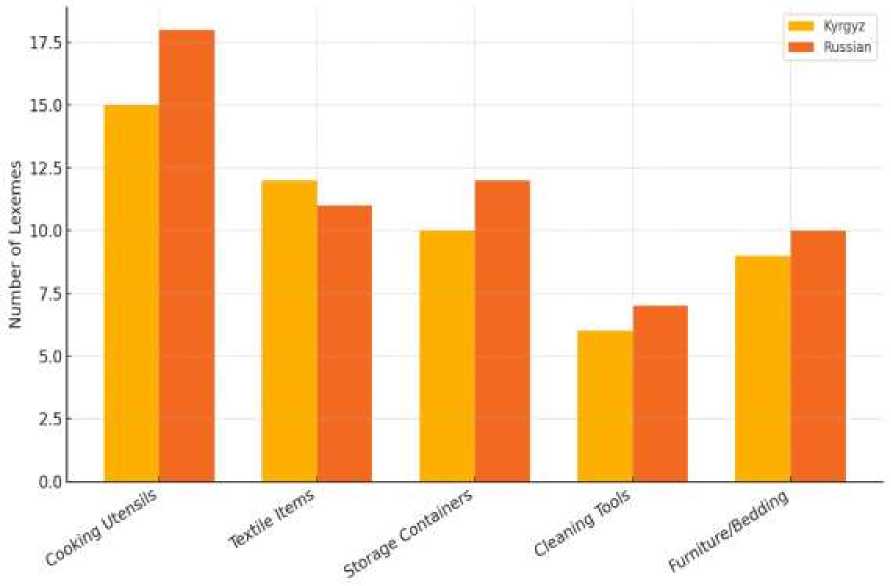

The Kyrgyz worldview privileges collective belonging, ritual continuity, and symbolic hospitality, with household objects becoming sacred carriers of tradition. Russian domestic metaphors, by contrast, are shaped by urbanization, privacy, and individual moral control, with household utensils deployed as tools of judgment and discipline. To facilitate comparative analysis and enhance interpretability of the collected data, a bar chart was constructed to visually represent the lexical density of household utensil terms in Kyrgyz and Russian across five semantic categories. This visual approach supports a clearer understanding of how each language encodes cultural values through domestic vocabulary and highlights asymmetries in categorical lexical saturation. Figure 1 illustrates the number of identified lexemes in each semantic category for both languages: The visual data representation confirms several key findings: Cooking utensils form the most lexically saturated category in both Kyrgyz (15 lexemes) and Russian (18 lexemes). This reflects the central role of food preparation in both cultures—not only as a daily activity but as a symbolic act of hosting, unity, and gendered labor [8, 9].

In Kyrgyz, terms like казан and очок are linked to family identity and ritual roles, while in Russian, печь and кастрюля reflect domestic infrastructure in settled peasant life. Textile items come next in density, especially in Kyrgyz, where items like төшөк and шырдак are culturally loaded with hospitality and ritual functions [5]. Russian equivalents exist but carry fewer symbolic associations. Storage containers are slightly more represented in Russian due to the presence of stationary living and permanent storage solutions (e.g., сундук, банка). Kyrgyz lexicon in this area is adapted to portable, organic, and multifunctional containers (чанач), consistent with nomadic life

Figure. Number of Household Utensil Lexemes by Semantic Category in Kyrgyz and Russian

Cleaning tools, as shown in the figure, are the least represented lexically in both languages, with 6 Kyrgyz and 7 Russian items. This scarcity may result from the low symbolic and cultural prestige of cleaning tasks, particularly in oral traditions. However, as discussed in Section 3.3, Russian culture compensates with a higher metaphorical usage of these tools [2, 7].

Furniture and bedding are moderately present in both languages. While Russian lexicon is more neutral and descriptive, Kyrgyz terms like көпөк (cradle) carry sacred, life-cycle meanings, emphasizing motherhood and protection. In sum, the visual data confirms that although Russian lexeme counts are slightly higher, especially in utilitarian categories like storage and cleaning, Kyrgyz vocabulary carries more cultural encoding, particularly in categories tied to ritual (cooking, bedding) and hospitality (textiles). The symbolic density reflects a worldview deeply informed by mobility, oral tradition, and communal interdependence. These findings support the perspective that language not only names objects but reflects culturally embedded practices and values, aligning with theories of cultural conceptualization and ethnolinguistic relativity.

|

Semantic Category |

Richest in Russian |

Richest in Kyrgyz |

Symbolic Density (Kyrgyz vs. Russian) |

|

Cooking Utensils |

✓ □ (more terms) |

✓ □ (symbolic) |

High in Kyrgyz |

|

Textile Items |

— |

✓ □ |

Very high in Kyrgyz |

|

Storage Containers |

✓ □ |

— |

Balanced |

|

Cleaning Tools |

✓ □ (slightly) |

— |

Higher metaphor use in Russian |

|

Furniture/Bedding |

✓ □ (slightly) |

✓ □ (sacred focus) |

High in Kyrgyz |

The findings of this study provide significant insight into how the semantic field of “household utensils” reflects broader cultural, historical, and cognitive differences between Kyrgyz and Russian linguistic communities. Although both languages share a common Eurasian space and exhibit typological similarities, their domestic vocabularies are shaped by distinct civilizational logics — nomadic and oral in Kyrgyzstan versus sedentary and textual in Russia. As demonstrated in Sections 3.1–3.4, the Russian lexicon includes a marginally greater number of household terms across most categories. This reflects Russia’s historically sedentary lifestyle, with greater emphasis on architectural stability, material accumulation, and permanent storage [8]. In contrast, the Kyrgyz lexicon, while numerically smaller, encodes a higher symbolic and ritual density, particularly in items tied to food, textiles, and hospitality. The semantic prioritization of cooking utensils and textile items in the Kyrgyz context suggests the centrality of the female domestic sphere, not only as a site of labor but also of cultural transmission and identity performance. The proverb “Казан кайнаса, капкагы менен” exemplifies how household objects function as moral and relational metaphors, particularly around marriage and kinship. Meanwhile, Russian metaphors—such as “не выносить сор из избы”—tend to moralize domestic boundaries, signaling a more privacy-oriented domesticity shaped by agrarian ethics and Orthodox-Christian values. The nomadic legacy of the Kyrgyz people influences how utensils are conceptualized: items like чанач (leather pouch) or көпөк (cradle) are not merely functional but symbolic of mobility, temporality, and family continuity. These terms often appear in ritual language or proverbs and are passed down generationally. In contrast, Russian items such as сундук (chest) or ведро (bucket) reflect a culture of spatial fixity, permanence, and object specialization. Sharifian’s (2011) theory of cultural conceptualizations helps explain these divergences: Kyrgyz utensils operate within a relational and cosmological schema, while Russian household terms are embedded in normative, moral, and practical schemas. The study also reveals that figurative usage of household terms is more culturally saturated in Kyrgyz cooking and textile domains, whereas Russian culture prefers metaphorizing cleanliness and moral control. This points to a larger difference in cultural narrative focus: the Kyrgyz lexicon reflects a celebratory and collectivist ethos, while the Russian one signals moral caution and private responsibility. Overall, the findings strongly support the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis that language encodes worldview. The comparison of Kyrgyz and Russian household terminology demonstrates that even seemingly mundane objects — like cauldrons, blankets, or brooms—carry deep cultural meanings and serve as vehicles of memory, identity, and value systems. These findings also reinforce the value of ethnolinguistic fieldwork and proverb analysis as tools for uncovering invisible structures of cultural cognition.

This study has explored and compared the functional-semantic field of household utensils in the Kyrgyz and Russian linguistic and cultural contexts, drawing upon lexical data, metaphorical usage, and visual representation. The findings confirm that while both languages exhibit a shared material foundation in domestic vocabulary, they diverge significantly in semantic density, cultural connotations, and metaphorical functions.

The Kyrgyz lexicon, shaped by a nomadic lifestyle and oral tradition, demonstrates a high symbolic load, particularly in categories such as cooking utensils and textiles. Household terms often reflect ritual significance, gender roles, intergenerational transmission, and collective identity. Proverbs and idioms in Kyrgyz encode deep moral and cosmological meanings through everyday items like казан, төшөк, or шырдак. In contrast, the Russian lexicon, rooted in a sedentary, agrarian culture and a strong written tradition, offers greater lexical diversity in utilitarian categories such as storage and cleaning. However, the symbolic load is uneven, with figurative language primarily emerging in moral and privacy-related metaphors, such as those involving cleanliness or social discretion (сор из избы).

The comparative visual and statistical data revealed that numerical lexical richness does not necessarily correlate with cultural or metaphorical depth. The Kyrgyz language, while slightly less lexically abundant, offers a more culturally saturated semantic field, confirming that language is a mirror of worldview and social structure. This analysis not only contributes to the field of ethnolinguistics and contrastive cultural studies, but also highlights the importance of preserving and documenting culturally embedded vocabulary, especially in minority and oral-based linguistic communities. Further research may extend this framework to other semantic domains (e.g., clothing, tools, architecture) or examine multilingual shifts in modern Kyrgyz-Russian bilingual speakers.