The Influence of The Family on the Development of a Criminal Personality

Автор: Željko Bjelajac, Joko Dragojlović, Dalibor Krstinić

Журнал: International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education @ijcrsee

Рубрика: Original research

Статья в выпуске: 2 vol.13, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The family is the fundamental unit of structure and function in every society, as well as for each individual as a part of that society. As a primary social group, the family plays a key role in shaping an individual’s personality and in the adoption of socially acceptable behavioral norms, while deviations in an individual’s behavior toward criminal tendencies have always been a subject of interest to society as a whole. This paper analyzes the influence of the family environment on the development of a criminal personality, focusing on dysfunctional family relationships, neglect, domestic violence, lack of supervision, and negative behavioral patterns transmitted across generations. Drawing on theoretical foundations from contemporary criminology and developmental psychology, as well as analyzing numerous empirical studies conducted in various social and cultural contexts, this work aims to provide a comprehensive insight into how adverse family conditions - such as emotional neglect, violence, divorce, dysfunctional relationships, and lack of parental supervision - may contribute to the development of deviant behavior in children and adolescents, as well as the formation of antisocial personality traits. Although criminal behavior is a complex social phenomenon that cannot be attributed solely to family influence, the findings of this research confirm that the family environment plays a crucial role in the socialization process and in shaping an individual’s moral compass. In other words, the family is recognized as one of the most influential factors in the formation of personal and social values that can significantly impact the development of criminal tendencies. The aim of this paper is to highlight the importance of prevention through the strengthening of family function and support for at-risk families as part of a strategy to combat criminal behavior.

Criminal behavior, development of criminal personality, family, social environment, psychological factors

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170210293

IDR: 170210293 | УДК: 343.9:316.362, 343.97 | DOI: 10.23947/2334-8496-2025-13-2-515-529

Текст научной статьи The Influence of The Family on the Development of a Criminal Personality

The family is a fundamental social institution that performs numerous functions essential to the development of the individual and the preservation of social order. As the primary and first social environment in which a person begins to interact with others, the family has a profound influence on the formation of identity, the adoption of social norms and values, and the development of the emotional, cognitive, and social structure of personality. The processes that take place within family relationships-whether positive or negative-leave deep marks on an individual’s development and influence future behavioral patterns, including those that may lead to deviance and criminality.

In this context, a criminal personality does not merely refer to a person who has committed a criminal offense, but to an individual who has developed personality traits that favor or encourage participation in criminal activities. Such traits include impulsiveness, aggressiveness, lack of empathy, antisocial tendencies, a propensity for manipulation, and disregard for social rules. A wide range of factors contribute to the emergence of these behavioral patterns-biological, psychological, social, and cultural-but among them, family factors are often the most significant and influential, particularly in early childhood and adolescence.

Dysfunctional family patterns-such as emotional neglect, physical or psychological abuse, authoritarian or overly permissive parenting styles, chronic parental conflict, divorce, alcoholism, substance abuse, and criminal behavior within the family-can significantly increase the risk of a child developing

-

*Corresponding author: zdjbjelajac@pravni-fakultet.info

© 2025 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

unacceptable forms of behavior. Lack of parental supervision, support, and a sense of security often leads children to seek belonging and validation in deviant peer groups, which can further steer them toward criminal activities. Additionally, families with low socioeconomic status, facing poverty, social exclusion, and marginalization, often lack the capacity to meet the child’s needs in a way that ensures healthy personality development.

Modern criminology, sociology, and developmental psychology are increasingly focusing on this specific aspect-the relationship between the family environment and criminal behavior. Theories such as social learning theory, control theory, ecological development theories, and other approaches link the stability and quality of family relationships with the likelihood that an individual will develop antisocial or delinquent behavior. Numerous empirical studies confirm a correlation between dysfunctional family structures and the emergence of criminal behavior, especially during adolescence, a period when individuals are most vulnerable to the influence of their immediate environment.

However, it is important to emphasize that there is no simple or direct causal relationship between the family and criminality. Criminal behavior is a complex phenomenon that cannot be attributed to a single cause. Ultimately, criminology has firmly adopted the scientific view that every perpetrator of a criminal offense is driven by specific motives arising from both subjective and objective circumstances, as well as various contributing variables that may influence criminal behavior ( Bjelajac, 2024 ). Many individuals who grow up in unfavorable family environments never become criminals, while some who come from functional and stable families still develop problematic behavior. For this reason, it is essential to view the influence of the family in interaction with other factors-individual, social, and economic.

The aim of this paper is to provide an analysis of the influence of the family on the development of a criminal personality, through a combination of theoretical and empirical approaches. The research will include a review of relevant literature, theoretical models, and research findings, as well as a critical analysis of the mechanisms through which family factors contribute to the formation of criminal behavior. Special attention will be given to the distinction between direct and indirect family influences, as well as to the possibilities for intervention and prevention at the family level.

Risk Factors Related to Parents and the Family

Some risk factors associated with the family are static, while others are dynamic. Static risk factors-such as a criminal history, parental mental health issues, or a history of childhood abuse-are unlikely to change over time. However, dynamic risk factors, such as poor parental behavior, domestic violence, or parental drug addiction, can be modified through appropriate prevention and treatment programs ( Family-Based Risk and Protective Factors and their Effects on Juvenile Delinquency: What Do We Know?, 2008 ). Risk factors have cumulative and interactive effects: the more risk factors a family is exposed to, the more likely it is to be considered high-risk. Moreover, children and adolescents exposed to certain risk factors are also more likely to follow a life path that may lead to delinquent behavior ( Was serman et al., 2003 ). This is due not only to the accumulation of risk factor effects but also to their interaction: the effect of one factor amplifies the effects of another, and so on. For example, parental alcoholism can trigger family conflicts, which then increase the risk of substance abuse ( Wasserman et al., 2003 ). There is extensive criminological literature suggesting that the family, as the basic building block of human society-especially the nuclear family-has a significant impact on child development. The family home is a natural school for children, where they internalize moral values through bonding, which are likely to guide their future development. Healthy and functional aspects of family life prevent antisocial behavior and/or delinquency, while the absence of proper parental care and negative parental influences, as well as growing up in dysfunctional families, may foster the development of such behaviors ( Dragojlović and Matijašević, 2013 ). Certain conditions and practices can increase the likelihood of externalizing behavior in childhood, violence, aggression, and criminal conduct during later stages of developmen.

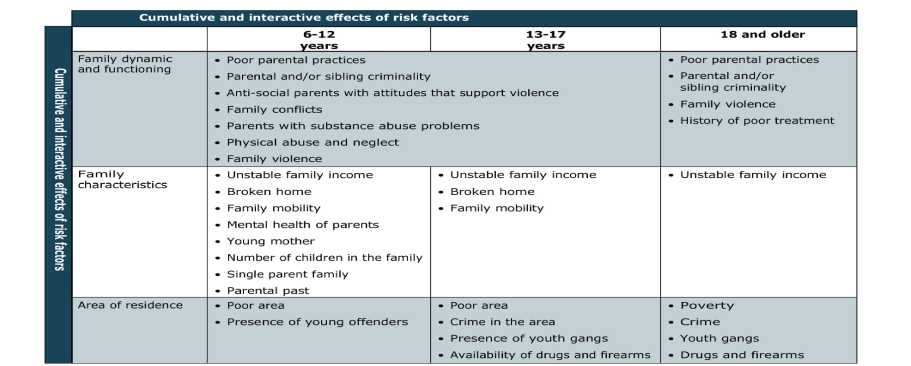

Tabela 1. Juvenile delinquency risk factors associated with family according to age of children and adolescents

Source: Family-Based Risk and Protective Factors and their Effects on Juvenile Delinquency: What Do We Know? (2008). Public Safety Canada. Retrieved April 5, 2025.

The table presents the cumulative and interactive effects of risk factors by age, divided into three developmental stages: children aged 6–12 years, adolescents aged 13–17 years, and young adults over 18 years of age. Risk factors are grouped into three main categories: family dynamics and functioning, family characteristics, and place of residence. The purpose of this classification is to highlight the complexity and interrelatedness of factors that negatively influence psychosocial development and potential delinquency among youth at different life stages. In all age groups, one of the dominant risk factors is inadequate parenting, manifested through a lack of supervision, authority, and emotional support. Among children and adolescents, particular risks include parental or sibling criminal behavior and the presence of parents who display antisocial attitudes or condone violence. Family conflicts, parental substance abuse, physical abuse and neglect, and domestic violence are additional destabilizing factors in the family environment. Among young adults over 18, the same patterns persist, with an added emphasis on a history of poor treatment during childhood and adolescence. For children aged 6–12, risk factors include unstable family income, broken families, frequent relocations, poor parental mental health, young mothers, large numbers of children in the household, single-parent households, and a negative family history. Among adolescents (13–17 years), risk factors remain similar with slightly fewer specific elements, while among young adults, economic instability remains the primary family-related risk. These findings suggest that early and chronic socioeconomic pressures have long-term consequences for development.

The table indicates that risk factors accumulate throughout childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood, with some early risks (e.g., poverty, domestic violence, neglect) persisting into later developmental stages. Moreover, there is interaction between personal, familial, and societal factors, creating a multifaceted burden that can contribute to the development of antisocial behavior. Understanding these connections is essential for designing comprehensive prevention and intervention programs targeted at vulnerable youth groups.

Based on the above, criminal behavior emerges as a multilayered phenomenon influenced by the dynamic interaction of individual, social, economic, and environmental factors. Among the most formative and enduring influences is the family environment, particularly the roles played by parents and primary caregivers. The family is the first and most important social unit in a child’s life, laying the foundation for behavioral patterns, emotional regulation, socialization processes, and moral values. It is within this microcosm that children first encounter the concepts of authority, discipline, empathy, and responsibility.

Dysfunctional family dynamics - such as neglect, abuse, lack of supervision, or deviant parental behavior - although not the sole cause, are consistently associated with the emergence and escalation of deviant and criminal behavior. Longitudinal studies, meta-analyses, and cross-cultural research over the past several decades have further confirmed that the family environment is not only a risk or protective factor in isolation, but also a context in which other ecological and psychological risks converge and interact ( Farrington and Malvaso, 2023 ). This chapter aims to thoroughly examine the various family risk factors that contribute to the development of criminal behavior, integrating classical criminological theories with contemporary empirical findings.

Parental supervision and self-control are among the most critical protective factors against delinquency. When supervision is lacking, children may fail to internalize social norms, face inconsistent consequences for misbehavior, or seek approval from deviant peer groups. Effective parental supervision involves awareness of a child’s whereabouts, peer associations, and daily activities, playing a key role in preventing opportunities for antisocial behavior ( Patterson, DeBaryshe and Ramsey, 1989 ). In this sense, the family environment and parental supervision serve as the first “safety measure” against antisocial behavior.

From a theoretical perspective, Hirschi’s social control theory argues that strong emotional bonds between children and their parents inhibit deviant behavior. These bonds are nurtured through consistent monitoring, emotional support, and the establishment of rules. When such bonds weaken, children become more susceptible to external pressures, including delinquent peer groups.

Complementing this view, the General Theory of Crime by Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990) emphasizes that self-control, largely developed in early childhood through effective parenting, is a key factor in criminal behavior. Poor parental supervision, lax discipline, and failure to model appropriate behavior can lead to the development of low self-control-a trait associated with impulsivity, aggression, and lack of foresight-characteristics often found among offenders.

Moreover, recent studies emphasize that the harmful effects of poor supervision are amplified in contexts of socioeconomic hardship, where external stressors already strain family relationships ( Far rington and Malvaso, 2023 ). Therefore, targeted interventions that strengthen parental involvement and teach supervision skills are essential components of delinquency prevention strategies.

Parenting styles and practices refer to the ways in which parents or caregivers interact with their children. Certain styles and practices appear more likely than others to lead to delinquency, and can therefore be considered risk factors ( Merdović, Počuča, Dragojlović, 2024 ; Hart et al., 1998 ). While parenting practices refer to specific behavioral patterns of parents, parenting styles relate to parent-child interactions that reflect parents’ attitudes toward their children and the emotional climate of the relationship ( Baumrind, 1991 ). The four main parenting styles are: authoritarian, permissive, neglectful/uninvolved, and authoritative.

Parenting style-defined by the dimensions of responsiveness (warmth) and demandingness (control)-is widely recognized as a determinant of youth behavioral outcomes. Baumrind’s typology describes four principal parenting styles: authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, and neglectful ( Baumrind, 1991 ). Among these, authoritative parenting, which balances firm boundaries with emotional support, is consistently associated with the lowest levels of delinquency and antisocial behavior.

Contemporary research further supports and elaborates on this approach. A cross-European study from 2023 showed that both authoritative and permissive parenting (high warmth, low control) were linked with positive outcomes among adolescents, including lower levels of externalizing behavior. In contrast, authoritarian (low warmth, high control) and neglectful (low warmth, low control) styles were associated with increased delinquency-especially when coupled with high family stress or instability, both social and economic.

Moreover, changes in parenting style over time-such as a shift from authoritative to disengaged parenting due to divorce, unemployment, or mental health issues-can have significant negative effects. A longitudinal study by Schroeder and Mowen (2014) found that such changes are linked to weakened attachment, reduced parental influence, and an increased risk of delinquency.

Attachment theory, developed by Bowlby (1982) , emphasizes the psychological mechanisms underlying these outcomes. Secure attachment, fostered through responsible and consistent caregiving, promotes emotional stability and social competence. In contrast, insecure or disorganized attachment-often the result of neglect, inconsistent care, or abuse-is correlated with anxiety, aggression, and difficulty forming trusting relationships. Lyons-Ruth et al. (1993) further observed that disorganized attachment in childhood predicts hostile and aggressive behavior in preschool years, which may evolve into delinquency during adolescence.

Family structure and stability have a significant impact on children’s developmental trajectories.

Incomplete families-such as those with single parents, divorced or remarried parents, or frequent changes in guardianship-are often associated with an increased risk of delinquency. However, recent research emphasizes that it is not the family structure itself that matters most, but rather the quality of relationships and the level of parental involvement within that structure.

Demuth and Brown (2004) pointed out that although adolescents from single-parent or blended families show higher rates of delinquency than those from two-parent households, much of this difference is explained by variations in supervision, attachment, and economic resources. A 2022 Swedish population study confirmed that adolescents living in complex, asymmetrical family structures are more prone to delinquent behavior, but also noted that strong parent-child attachment mitigates this risk (Svensson and Johnson, 2022).

There is strong evidence that family instability, marked by frequent relocations, parental conflict, or shifts in living conditions, has a disruptive impact on children’s psychological well-being. Exposure to chronic parental conflict or domestic violence creates a climate of fear and insecurity, fostering maladaptive coping strategies such as aggression, defiance, and emotional withdrawal ( Jaffe, Wolfe and Wilson, 1990 ).

The cumulative impact of family instability can erode trust in authority, reduce academic achievement, and increase affiliation with deviant peer networks, thereby heightening the risk of criminal involvement.

Parental criminality and substance abuse are among the most significant intergenerational predictors of delinquency. Children learn behavior through observation and imitation, as outlined in Bandura’s Social Learning Theory (1977). When parents themselves engage in criminal or addictive behavior, children may internalize such conduct as normative-perceiving it as normal and acceptable behavior to be emulated (Ibid).

Empirical studies have consistently shown that children of incarcerated parents or those who abuse substances face a higher risk of various adverse outcomes, including academic failure, mental health disorders, and criminal behavior ( Murray and Farrington, 2005 ). Farrington and Malvaso (2023) further observe that the combination of parental convictions and authoritarian discipline is particularly predictive of juvenile delinquency.

Parental substance abuse also creates a home environment characterized by emotional unavailability, neglect, and often violence. These conditions undermine the formation of secure attachments and reduce the likelihood that parents will provide consistent discipline, support, or supervision ( Pearson, D’Lima and Kelley, 2012 ). Children raised in such settings often experience trauma, instability, and social isolation-all of which contribute to criminal trajectories. Due to this familial environment, children tend to normalize the criminal milieu, where substance abuse, alcohol misuse, and frequent incarceration are part of daily life. As a result, they are less likely to perceive such behaviors as unacceptable.

Although economic hardship and family stress do not constitute a direct or immediate cause of criminal behavior, they create an environment in which numerous other risk factors are intensified and activated, potentially leading to the development of deviant patterns. According to the Family Stress Model, economic difficulties result in increased levels of parental stress, frustration, and intra-family conflict, which in turn undermine the quality of parenting practices and increase the likelihood of problematic behaviors in children ( Conger et al., 1992 ).

Financial instability often leads to reduced emotional and cognitive involvement of parents in upbringing, more frequent use of punitive or even violent discipline, and limited capacity to provide an enriching socio-educational environment. Such families frequently lack access to essential social and health services, including mental health support, quality education, and extracurricular programs that serve a preventative function. Farrington and Malvaso (2023) emphasize that the synergistic effect of economic hardship and factors such as harsh parenting or a family history of criminality significantly increases the risk of juvenile delinquency.

Empirical evidence from evaluations of social interventions-such as the Perry Preschool Project, Elmira Nurse–Family Partnership, and Multisystemic Therapy (MST)-shows positive long-term effects in reducing delinquency levels. These programs succeed by enhancing parenting skills, stimulating early educational development, and targeting structural deficits in the social and familial context ( Henggeler et al., 2009 ).

These interventions point to the need for a holistic, multidimensional approach that combines individualized family support with broader social and legal reforms. Such an approach aligns with modern understandings in the fields of criminal justice and social policy, which emphasize the importance of preventative action through reducing social exclusion and strengthening family-based protective factors.

Abuse, neglect, and traumatic experiences represent the most severe forms of family dysfunction and are strongly linked to both immediate and long-term behavioral problems. Physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and chronic neglect disrupt healthy psychological development, often resulting in emotional dysregulation, aggression, and impaired interpersonal functioning ( Widom, 1989 ).

The “cycle of violence” hypothesis suggests that individuals who experience abuse are more likely to engage in violent or criminal behavior later in life. This intergenerational transmission of violence is supported by a growing body of neurobiological and psychological evidence indicating that early trauma alters brain development, stress response systems, and moral reasoning. Contemporary studies also explore how exposure to harsh disciplinary practices-such as frequent yelling, humiliation, or physical punishment-can lead to the development of dark personality traits, including narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy, all of which are associated with criminal behavior. Children exposed to neglect, meanwhile, often struggle with attachment disorders, cognitive delays, and a lack of social competence, increasing their risk of peer rejection and involvement in delinquent subcultures (Dubowitz et al., 2002). Intervention programs that address trauma through therapeutic, educational, and family-based approaches have been shown to reduce behavioral problems and improve resilience in at-risk children.

Siblings are among the longest-lasting relationships in most people’s lives - from early childhood to old age . Older blood relatives play an important role in the development and adjustment of children and adolescents, including the emergence of problematic behavior. This influence arises not only from frequent and often emotionally intense interactions, but also from the impact of siblings and their role in the dynamics of family relationships, which can sometimes be highly complex. It is well known that siblings often imitate one another, with younger children most commonly mimicking their older brothers and sisters. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that such direct and/or indirect influences and their variations play a significant role in shaping the development of aggressive behavior. Compared to the influence of peers, parents, and schools, this factor has been less explored, even though many studies indicate that sibling delinquency is closely linked to adolescent delinquency, especially in early adolescence. In general, siblings learn from one another, with younger children predominantly learning from older ones ( Bjelajac, 2023, pp. 66–67 ). This domain of influence on the formation of delinquent behavior in adolescents is particularly evident in the adoption of risky behavior patterns such as alcohol consumption, smoking, use of psychoactive substances, and early sexual activity. The first signs of such influence are often observed in neglect of school responsibilities and reduced commitment to education. In contrast, functional family relationships, including consistent parenting styles and emotional closeness and support among siblings in early childhood, are associated with the development of numerous prosocial behaviors and more favorable life outcomes.

We have emphasized that parents likely have one of the greatest influences on a child’s life. The development of children is significantly shaped by both the biological and psychosocial aspects of parenting, including parental psychopathology ( Ollendick and Herson, 1989 ). In this regard, it is not surprising that parents and children often exhibit similar psychopathological symptoms. Why do we observe this connection between parental and child psychopathology? The reason may lie in the fact that children learn, imitate, and internalize dysfunctional parental behaviors. Children are at the greatest risk of developing the type of psychopathology demonstrated by their parents due to environmental influences and patterns such as parental modeling ( Burstein, Ginsburg, and Tien, 2010 ; Burstein et al., 2010 ). Parental psychopathology has been observed to be a strong predictor of child psychopathology. Children of parents with anxiety or depressive disorders are more likely to be diagnosed with similar disorders than children whose parents do not suffer from these conditions. The likelihood of a child developing a disorder is five to six times higher if the parent has anxiety, depression, or both ( Beidel and Turner, 1997 ).

It is therefore evident that, in a significant number of cases, there is a strong connection between childhood depression and anxiety and parental psychopathology. Even parental alcoholism increases the risk of various negative outcomes in children. The presence of paternal alcoholism, in particular, can contribute to antisocial behavior and maladjustment in sons ( Bjelajac, 2023, p. 68 ). Accordingly, it is observed that parents with a history of mental illness can influence child development through various mechanisms. Understanding these influences can play an important role in shaping early intervention programs and preventive strategies aimed at reducing anxiety and depression among children.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2022) ( Single Mother Statistics, 2023 ), single-parent households have become an accepted way of life . Approximately 11 million families with children under the age of 18 live in single-parent households. The data show that vulnerable single motherhood has become so common in the United States that 80 percent of single-parent households are led by single mothers, with nearly one-third living in poverty. Two-parent households may be broken due to various circumstances -death, abandonment, divorce, or separation. At the same time, there is a growing number of women who deliberately avoid marital relationships and conceive through anonymous donors, framing this choice as an act of free will and a modern lifestyle, even though such decisions may be detrimental to the biopsy-chological development of the child. This is symptomatic because many authors reveal data showing that delinquency is more likely among children from homes where parents are divorced or separated. Thus, it can be concluded that a single-parent or broken home, as some describe it, may induce criminal behavior, especially when interacting with other risk factors ( Bjelajac, 2023, pp. 62–63 ).

As can be seen, the influence of the family on the development of criminal behavior is profound and multifaceted. While healthy, supportive, and structured family environments act as strong protective factors, dysfunctional family dynamics significantly increase the risk of delinquency and criminal activity. Poor parental supervision, ineffective parenting styles, family instability, parental criminality, economic hardship, and exposure to abuse and neglect all contribute to a child’s vulnerability to antisocial behavior.

It is important to note that these risk factors rarely operate in isolation. Their interaction often amplifies their effect, creating a range of challenges that hinder normative development. Addressing these issues requires early, comprehensive, and context-sensitive interventions that support families in building nurturing environments. Prevention strategies must focus not only on the individual but also on enhancing parenting skills, improving family stability, reducing economic disparities, and delivering trauma-informed care.

Quantifying the Impact of the Family on the Development of a Criminal Personality

Quantifying the impact of the family on the formation of a criminal personality involves assessing the extent to which family factors statistically predict, correlate with, or contribute to the development of antisocial traits and criminal behavior.

Although no single variable can fully explain criminal behavior, a growing body of research has identified consistent familial predictors-such as parenting quality, family structure, and parental criminal history-that correlate with an increased likelihood of criminal outcomes ( Farrington, 2002 ; Murray and Far rington, 2005 ). These findings underscore the central role of the early family environment in individuals’ social development and their potential deviation from societal norms. This chapter explores how these factors are quantified, the strength of their associations, and their interaction with individual and environmental variables in shaping criminal personality.

Longitudinal and cohort studies provide some of the most robust evidence for quantifying the influence of the family. These studies follow individuals over extended periods and track various familial and behavioral variables, allowing researchers to identify causal links rather than mere correlations.

One of the most frequently cited studies is the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development , led by David Farrington, which followed 411 boys from working-class families in London from childhood into adulthood. The study revealed that children from families with poor parental supervision, harsh discipline, and a parental criminal background were significantly more likely to be convicted of crimes later in life ( Farrington, 2002 ). The study quantified that approximately 6% of families accounted for more than 50% of all convictions within the cohort, illustrating the concentrated nature of familial risk and the disproportionate impact of certain family environments.

Similarly, the Pittsburgh Youth Study (PYS) and the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study from New Zealand provided quantitative data linking poor parenting, parental substance abuse, and early family adversity with persistent criminal behavior. These studies often utilize multivariate regression analyses to isolate the effects of family variables from other predictors such as socioeconomic status or school environment ( Loeber et al., 2008 ; Moffitt, 1993 ). Such analytical separation helps to more precisely determine the unique contribution of family variables in the trajectory toward criminality.

The predictive strength of parental criminality is one of the most powerful familial predictors of future offending. Murray and Farrington (2005) analyzed data from multiple cohort studies in the UK and US and found that children of convicted parents were more than twice as likely to be convicted themselves, even after controlling for socioeconomic factors. This suggests a strong intergenerational transmission of criminal behavior.

A meta-analysis conducted by Besemer et al. (2011) found that the odds ratio for intergenerational transmission of criminal behavior was approximately 2.4, indicating a moderate to strong predictive association. This transmission is attributed not only to genetic factors but also to behavioral modeling within the family, social stigma, and shared adverse conditions. Children who grow up observing criminal behavior may internalize such behaviors as acceptable, especially in the absence of positive role models.

Quantitative findings from the Cambridge study also showed that 63% of boys whose fathers had criminal convictions were later convicted themselves, compared to only 30% among those whose fathers had no criminal record ( Farrington, 2002 ). These figures demonstrate that a parental criminal history represents a strong risk marker that further exacerbates other adverse conditions.

Various criminological models and risk assessment tools include family variables as part of their predictive algorithms. For example, the Youth Level of Service / Case Management Inventory (YLS/ CMI) includes family circumstances and parenting style as key domains of risk, emphasizing that the family is not merely a contextual background but a quantifiable determinant of youth outcomes.

In actuarial risk assessments, family-related indicators are often weighted according to their statistical correlation with delinquent outcomes. These models typically assign higher risk scores to youth who experience neglect, inconsistent parenting, or have parents with a criminal history. Studies evaluating the predictive validity of these tools have shown that including family variables increases the accuracy of predictions regarding recidivism and persistent criminal behavior ( Schmidt et al., 2011 ).

Multivariate regression models and structural equation modeling (SEM) techniques are also frequently used in academic research to quantify the relative contribution of family factors. For instance, Loeber et al. (2008) used SEM to demonstrate that poor parental supervision significantly mediates the relationship between socioeconomic disadvantage and juvenile delinquency. These advanced statistical methods allow researchers to visualize both direct and indirect effects within complex systems of variables.

Quantification of parenting quality and its outcomes -i.e., attempts to measure the quality of parenting-often involves multi-item questionnaires and observational checklists. Among them are the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ) and the Parenting Scale , which assess dimensions such as positive involvement, inconsistent discipline, and poor supervision. These tools provide quantitative metrics that can be linked to behavioral outcomes in youth.

Meta-analyses of such studies have shown moderate to strong correlations between poor parenting practices and antisocial behavior. For example, Hoeve et al. (2009) , in a meta-analysis of 161 studies, found that poor parental supervision had a medium effect size of r = .23 in predicting delinquency, while harsh discipline had an effect size of r = .19. These findings are statistically significant and consistent across multiple samples, thereby strengthening the reliability of these associations.

Although moderate, these effects carry substantial weight in behavioral sciences and indicate that family-based interventions can significantly reduce youth offending when parenting quality is improved. Intervention programs that enhance parenting practices-such as consistent discipline, emotional support, and supervision-can serve as highly effective strategies for crime prevention.

In the context of the cumulative and interactional nature of risk factors , it is observed that family-related risk factors rarely operate in isolation. Instead, they interact with other domains such as peer influence, education, and community conditions to either amplify or mitigate risk. This cumulative risk model is supported by studies showing that the presence of multiple risk factors exponentially increases the likelihood of criminal behavior ( Rutter, 1979 ).

In the Rochester Youth Development Study , youth exposed to three or more family risk factors exhibited delinquency rates more than four times higher than their peers without such factors ( Thornberry et al., 2003 ). These findings have led to the use of cumulative risk indices in research and policy to better capture the degree of vulnerability within families. The more adverse conditions a child experiences, the greater the likelihood of behavioral and emotional problems that may lead to criminality.

Additionally, research conducted by Farrington and Malvaso (2023) highlights how combinations of family risk factors-such as parental criminality, harsh parenting, and poverty-interact and significantly increase the probability of juvenile delinquency, more so than any single factor alone. These interaction effects underscore the need for holistic interventions that address multiple dimensions of family dysfunction.

Thus, quantifying the impact of the family on the formation of a criminal personality requires a nuanced synthesis of theoretical models and empirical data. Through numerous longitudinal and meta-analytical studies, family variables-particularly parenting style, parental criminal history, and family stability-have consistently shown moderate to strong associations with criminal behavior.

The predictive strength of these variables varies depending on the population and cultural context but remains significant even when controlling for other social and economic factors. While no single measure can fully capture the complexity of criminal development, combining risk assessment tools, the cumulative risk model, and longitudinal tracking enables better understanding, prediction, and ultimately, prevention of criminal behavior stemming from the family environment.

These insights also emphasize the crucial importance of early interventions and family-based prevention programs. By identifying at-risk families and providing targeted forms of support, policymakers and social workers can interrupt the trajectory from family dysfunction to criminal outcomes, thereby fostering healthier developmental paths for vulnerable children.

Protective Factors as a Response to Risk Factors

The complex interplay between individual, familial, interpersonal, and societal dynamics contributes significantly to the risk of youth violence. Many risk factors associated with violent behavior among young people are closely linked to prolonged exposure to toxic stress, which adversely affects brain development in children and adolescents. Such toxic stress may arise from various adverse conditions faced by youth, including poor living environments, substance abuse, and other forms of instability ( Bjelajac, 2023, p. 81 ).It is essential to recognize that no effort aimed at preventing criminal behavior can be effective or sustainable unless it addresses the underlying causes of such behavior. The elements that serve as a buffer between the presence of risk factors and the onset of delinquency are known as protective factors ( Bjelajac, 2023, pp. 82–83 ). Risk factors are negative influences that affect individuals or communities, potentially leading to increased levels of crime, victimization, and fear within society. Conversely, protective factors are positive influences that enhance individual well-being and community safety, reducing the likelihood of criminal involvement or victimization. Strengthening and reinforcing existing protective factors contributes to the resilience of both individuals and communities, enabling them to better withstand and manage exposure to risk. This approach highlights the importance of proactive strategies that focus not only on mitigating risk but also on fostering protective environments and relationships ( Family-Based Risk and Protective Factors and their Effects on Juvenile Delinquency: What Do We Know?, 2008 ; Kovačević Lepojević, Merdović, and Živaljević, 2022 ).

Considering that resilience to stress and negative influences varies from person to person, and that young people are constantly exposed to numerous challenges and risk factors, the question arises: to what extent is an individual’s psychophysical structure capable of withstanding such pressures? Early identification of risk and the development of protective mechanisms play a crucial role in building resilience, with the family environment being particularly significant. Prevention within the family-through supportive relationships, open communication, stable emotional bonds, and active parental care-forms the foundation for the development of healthy behavioral patterns in children and adolescents.

Although the education system, community, and society at large are also important, research shows that timely measures within the family context can significantly reduce the risk of delinquent behavior. Ongoing parental education, strengthening of family competencies, and raising awareness about the importance of a safety-oriented culture are key components of preventive strategies that are both sustainable and effective over the long term. Prevention that begins in the home often has the most far-reaching impact on protecting young people and guiding their development in a positive direction. The family environment, as the earliest and most enduring developmental anchor, plays a fundamental role in shaping the attitudes, values, and behavioral patterns of children and adolescents. The multiple challenges of contemporary society-from substance abuse and digital violence to extremist narratives and technological misuse-highlight the need for resilience and responsible behavior to be cultivated first and foremost within the family ( Bjelajac and Jovanović, 2013 ; Bjelajac and Filipović, 2020 ; Bjelajac, Matijašević and Počuča, 2012 ; Zirojević and Bjelajac, 2013 ).

The narrative of the development and prevention of criminal behavior involves complex cause-and-effect relationships that do not allow for simple solutions. Certain risk factors-such as global economic disruptions or high unemployment rates-are often structurally conditioned and resistant to rapid change. Numerous studies point to a correlation between low socioeconomic status and an increased likelihood of antisocial and deviant behavior.

|

Table 2 . Protective factors associated with family |

||

|

Family dynamic and functioning |

Family characteristics |

Area of residence |

|

|

|

Source: Family-Based Risk and Protective Factors and their Effects on Juvenile Delinquency: What Do We Know? (2008). Public Safety Canada. Retrieved April 5, 2025.

Nevertheless, there are also risks that can be mitigated through targeted intervention, such as deficits in parental competencies. Through educational programs and professional support, it is possible to improve parenting skills and thereby strengthen the family environment as an important protective factor. Since risks emerge at various levels-individual, familial, school-based, and broader societal-protective measures must also be multilayered, coordinated, and tailored to specific challenges. Naturally, such approaches have their limitations, but they represent an important step in the strategic prevention of criminal behavior, particularly when it comes to vulnerable youth populations.

Materials and Methods

As part of the implementation of this descriptive research, research questions were formulated with the aim of enabling a systematic examination of the family’s influence on the formation and evolution of criminal behavior. Through the application of qualitative research methods-primarily content analysis, case studies, and in-depth analytical approaches-it was possible to explore the complex social and psychological processes underlying the development of deviant and antisocial behavior patterns within the family environment. The intent was to ensure a holistic and interdisciplinary understanding of the phenomenon in question.

The goal of this approach was to provide well-argued answers to the research questions through contextualized and detailed interpretation, in direct correlation with the primary aim of the paper: to identify and analyze the influence of the family on the development of a criminal personality, as well as the mechanisms of its effect in the context of the emergence and progression of an individual’s criminal behavior.

Additionally, by using the method of comparative analysis, the research facilitated a better understanding of the layered and multifactorial nature of criminality, as well as the role, place, and influence of the family in the development of a criminogenic personality. It also pointed to contextual and cultural specificities that may influence variations in the etiology of criminal behavior.

For the purpose of this paper, the survey has been designed and conducted, between February 17, 2025 and June 2, 2025, with a sample of 395 students from the Faculty of Law for Commerce and Judiciary in Novi Sad. The purpose of the survey was to examine students’ perceptions of key family-related factors contributing to the formation of a criminal personality. The survey question, the students, had to answer was: Which of the following family-related factors, in your opinion, contribute most to the development of criminal behavior among young people? (Select up to three factors you consider the most important.) An overview and the results will be presented and discussed at the relevant part of the paper.

Results

The research was conducted from February 17, 2025, to June 2, 2025, on a sample of 395 students from the Faculty of Law for Commerce and Judiciary in Novi Sad. The purpose of the survey was to examine students’ perceptions of key family-related factors contributing to the formation of a criminal personality.

Survey Question: Which of the following family-related factors, in your opinion, contribute most to the development of criminal behavior among young people? (Select up to three factors you consider the most important.)

Response Options:

-

1. Abuse, neglect, and traumatic childhood experiences

-

2. Parents’ mental illness (parental psychopathology)

-

3. Lack of emotional connection with parents

-

4. Domestic violence among family members

-

5. Alcoholism or addiction of one or both parents

-

6. Poverty and poor material conditions

-

7. Lack of parental control and supervision

-

8. Criminal history of the parents

-

9. Divorce and dysfunctional family dynamics

-

10. Absence of one parent (e.g., physical or emotional)

Table 3. Survey Results (most frequently selected answers, by number of responses)

|

No. |

Risk factor |

Results |

Percentage |

|

1 |

Abuse, neglect, and traumatic childhood experiences |

93 |

23,6% |

|

2 |

Parents’ mental illness (parental psychopathology) |

81 |

20,6% |

|

3 |

Lack of emotional connection with parents |

15 |

3,8% |

|

4 |

Domestic violence among family members |

31 |

7,8% |

|

5 |

Alcoholism or addiction of one or both parents |

27 |

6,8% |

|

6 |

Poverty and poor material conditions |

25 |

6,3% |

|

7 |

Lack of parental control and supervision |

19 |

4,8% |

|

8 |

Criminal history of the parents |

74 |

18,7% |

|

9 |

Divorce and dysfunctional family dynamics |

17 |

4,3% |

|

10 |

Absence of one parent (e.g., physical or emotional) |

13 |

3,3% |

Source: Author’s calculation

The survey presented in Table 3 identifies the most frequently selected risk factors perceived to influence negative outcomes in individuals, such as deviant behavior, social maladjustment, or psychological disorders. The respondents’ answers highlight a clear pattern: the family environment, especially during childhood, plays a central role in shaping an individual’s development and future behavior.

The most frequently identified risk factor is “Abuse, neglect, and traumatic childhood experiences”, selected by 23.6% of respondents. This indicates a strong recognition of the lasting effects that early trauma can have on a child’s emotional, social, and psychological development. Childhood maltreatment is often linked to disruptions in attachment, emotional regulation difficulties, and a higher likelihood of adopting maladaptive coping strategies. The second most cited risk factor is “Parents’ mental illness (parental psychopathology)” at 20.6%, suggesting that the psychological well-being of caregivers is seen as critical to a child’s healthy upbringing. Children growing up with mentally ill parents may be exposed to instability, emotional unavailability, or even unsafe environments, all of which can lead to developmental delays or behavioral issues. Closely following is “Criminal history of the parents”, at 18.7%. This reinforces well-established criminological theories regarding the intergenerational transmission of criminal behavior. Such environments often normalize antisocial behavior and may expose children to high-stress situations, poor role models, and social marginalization.

The dominance of these top three risk factors underscores a key insight: adverse family conditions, particularly in early childhood, are perceived as the most influential contributors to negative life outcomes. The responses reflect a biopsychosocial understanding of human behavior, where biological vulnerabilities (e.g. inherited mental illness), psychological trauma, and social influences (e.g. criminal behavior modeled by parents) interact in complex ways.

Mid-ranking factors such as domestic violence (7.8%), alcoholism or addiction (6.8%), and poverty (6.3%) are also critical, though perceived as somewhat less directly damaging than abuse or parental mental illness. These factors contribute to household instability and increase the likelihood of emotional distress, neglect, or exposure to harmful situations.

Less frequently mentioned were lack of emotional connection (3.8%), divorce or dysfunctional family dynamics (4.3%), and absence of a parent (3.3%). While these can also negatively affect children, they may be seen as more manageable or less inherently damaging, particularly if mitigated by other protective factors (e.g. support from extended family, school, or community).

The survey results support existing psychological and sociological research emphasizing the importance of early childhood experiences and parental influence. They suggest that policies and interventions should focus on preventing child abuse, supporting families affected by mental illness, and disrupting cycles of intergenerational criminality. This can be achieved through trauma-informed care, mental health services for parents, social work interventions, and targeted education or mentorship programs for at-risk youth.

Furthermore, the relatively low frequency of responses related to divorce or single parenting may indicate a shift in societal attitudes, reflecting increased normalization of these family structures and a more nuanced understanding that their impact depends on context, not merely presence.

In conclusion, the table provides valuable empirical support for the view that family environment- especially when marked by trauma, mental illness, or criminal behavior-is a central risk factor for developmental and behavioral challenges. Future research and social policy should prioritize early intervention and holistic family support as preventive measures.

Discussion

The previous chapters have provided a comprehensive overview of how the family influences the formation of a criminal personality-from identifying basic risk factors, through their detailed explanation, to attempts at quantification through longitudinal and empirical research. In this discussion, we will analyze how all these findings together contribute to our understanding of the phenomenon, and what dilemmas, limitations, and opportunities emerge for further research and action.

The chapter dedicated to family risk factors demonstrated that dysfunctional family patterns-such as neglect, domestic violence, chronic conflict, emotional detachment, and poor behavioral control-have a clear correlation with an increased likelihood of developing antisocial behavior in children. These findings serve as the foundation for understanding the criminogenic role of the family, as well as a basis for identifying at-risk groups. Even at this stage of the paper, a crucial question arises: are these factors causes, triggers, or merely indirect indicators of deeper socioeconomic problems? The answer is not straightforward, which points to the need for multilayered models of analysis that also account for the broader social context. The chapter focusing on quantitative approaches raises the issue of the measurability of family factors and their predictive power regarding criminal behavior. Studies such as the Cambridge, Dunedin, or Pittsburgh Youth Study offer compelling evidence of the significance of the family environment. Still, no matter how impressive the numbers-such as findings showing that children of convicted parents are twice as likely to be convicted themselves-quantification comes with certain limitations. For instance, there is the risk of overgeneralization, the neglect of cultural context, and the overlooking of individual protective factors. In other words, numbers speak, but they do not explain everything.

A shared theme of both chapters is the emphasis on early childhood and formative family relationships as key determinants of personality development. However, what especially deserves attention is the interaction among risk factors, their overlap, and their cumulative effects. It is precisely this complexity that explains why uniform solutions and approaches often fail to yield long-term results. The family is not an isolated system-it functions within an environment shaped by economic, cultural, and political influences. Therefore, any consideration of family-related factors must be broadened to include the wider societal framework.

From the current analysis emerges a need to balance two narratives: the narrative of risk and the narrative of resilience. While it is important to identify at-risk families, it is even more important to empower them-not through exclusion, but through inclusive policies and support. In this sense, quantitative research should not be used to stigmatize, but rather to enable early identification of needs and the development of preventive programs. Additionally, it is important to ask who produces, interprets, and uses data about family factors. Are they experts, policymakers, or institutions that often operate through a punitive rather than a preventive logic? If family factors are known to have predictive power, then it would be logical for society to invest in prevention-not solely in repressive mechanisms.

In conclusion, the key contribution of the previous chapters lies in the integration of various theoretical and empirical perspectives, which call for a holistic understanding of the family as a space where both risk and protective factors simultaneously develop. The family can play an ambivalent role-it can be a supportive environment for healthy development, but also a source of dysfunction and destructive behavior. In this light, the survey conducted among 395 students at the Faculty of Law for Commerce and Judiciary in Novi Sad further highlights this complexity, confirming that abuse, neglect, and parental psychopathology are recognized as dominant risk factors in the formation of a criminal personality. These findings call for continued dialogue between theory and practice, between statistics and life stories, and point to the urgent need for prevention that begins within the family environment.

Conclusion

The analysis of family factors in the context of criminal behavior reveals a complex and multilayered picture in which the family plays a key-but not exclusive-role in the formation of criminal personality. Through a review of theoretical approaches, the identification of specific risk factors, and their empirical quantification, this paper demonstrates that while the influence of the family is undeniably strong, it must be understood within a broader social and individual context.

The family represents the first and most intense social environment that shapes a child’s values, norms, and behavior patterns. Through early emotional relationships with parents and other family members, a child develops foundational models that later influence their decisions and actions. In this sense, it has been shown that factors such as parental supervision, emotional warmth, consistent discipline, and the absence of violence are key protective elements that reduce the risk of criminal behavior. On the other hand, dysfunctional family patterns-including violence, neglect, parental criminality, and chaotic family structure-represent risk factors that significantly increase the likelihood of developing antisocial traits and behaviors. Although these factors do not predetermine an individual’s fate, their presence contributes significantly to the cumulative effect of risk, especially when protective factors from other life spheres (school, community, peer relationships) are lacking.

Empirical research, including longitudinal studies such as the Cambridge Study, the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, and the Pittsburgh Youth Study, has enabled the quantification of family-related factors and confirmed their predictive power. Based on these findings, it is clear that certain forms of parental behavior and family dynamics can be considered early indicators of risk for criminal development.

However, it is important to emphasize that quantification must not lead to a deterministic approach. No child is doomed to a criminal path simply because they come from a high-risk family. This is precisely why it is necessary to develop and implement policies that not only identify at-risk cases but also provide active support to families in crisis situations. Prevention must be holistic, systemic, and long-term, with a focus on strengthening family competencies, promoting positive parenting, and reducing socioeconomic inequalities.

In conclusion, it can be said that the family has the potential to be both the cause and the solution to the problem of criminality. It can be a source of serious difficulties and risk factors, but also a space from which resilience, support, and the opportunity for change emerge. Criminological policies that recognize this and act accordingly are more likely not only to reduce crime rates but also to contribute to a healthier and more just society overall. Ultimately, strengthening the family unit remains one of the most effective means of preventing youth delinquency and breaking the intergenerational cycle of criminal behavior.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all respondents and to the academic community within the Faculty of Law of the University Business Academy in Novi Sad for their support in publishing this manuscript.