Toxic communication zones and emotive markers in the Russian-language work environment

Автор: Pavlova E.B., Valeeva N.G.

Журнал: Вестник Волгоградского государственного университета. Серия 2: Языкознание @jvolsu-linguistics

Рубрика: Развитие и функционирование русского языка

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.22, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The paper addresses the problems of toxic communications in the workplace and considers lexical and grammatical means of expressing emotions. The material for the study was former workers’ comments and anonymous questionnaires completed by current employees of Russian enterprises. Based on empirical data processed under Fisher’s angular transformation method, which enabled highly accurate comparison of small samples, three toxic communication zones in industrywere identified: the zones of toxic bosses, toxic management, and toxic workers. The authors performed a Likert scale survey of executives, managers, and workers. The results of single-factor and two-factor analysis of variance helped us to establish the relation between toxic communication and so-called toxicity focuses, that is, standard topics which are constantly in the centre of destructive communications in the workplace. The paper determines lexical and grammatical means of expressing emotions which are emotive markers of toxic communication (affectives and connotatives). It shows that abusive words and phrases, zoolexics, vernacular and slang vocabulary, colloquial emotionally colored vocabulary, and phraseological units are equally relevant for all three zones of toxic communication zones. Quantitative analysis of the identified emotive markers in terms of their structural and morphological characteristics revealed the abundance of interjections, nouns, adjectives, and adverbs of degree and intensity.

Toxic communication, toxic communication zones, work communication, markers of toxicity, affectives, connotatives, lexical and grammatical means of expressing emotions

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149143717

IDR: 149143717 | УДК: 811.161.1:159.942 | DOI: 10.15688/jvolsu2.2023.2.2

Текст научной статьи Toxic communication zones and emotive markers in the Russian-language work environment

DOI:

The concept “toxic” has recently become widespread, as evidenced by the fact that in 2018 Oxford Dictionaries chose “toxic” as its international word of the year, selecting it from a shortlist that included such politically inflected contenders as “gaslighting”, “incel” and “techlash”. But the word was chosen less for statistical reasons. Katherine Connor Martin, the company’s head of U.S. dictionaries, said the word was chosen more for the sheer variety of contexts in which it has proliferated, from conversations about environmental poisons to laments about today’s poisonous political discourse. The Oxford Dictionary website also reports that “toxic” has “truly taken off into the realm of metaphor, as people have reached for the word to describe workplaces, schools, cultures, relationships and stress” [McKirdy, 2018]. The results of Google search queries (1,440,000,000 occurrences) in 2022 show that the word is still relevant. In English, phrases with the word “toxic” regularly describe communication in the field of industrial and business relations: The Toxic Workplace; Toxic Work Environments; toxic communication, a toxic working environment, toxic people, toxic behaviour at the workplace, A Toxic Office, a Toxic Workplace Culture, a Toxic Work Relationship, Toxic Coworkers, Toxic Jobs, toxic work environment. For example, American news and information website Axios says White House As “Most Toxic Working Environment on the Planet”. A similar trend is observed in the Russian language as well. In addition to “containing toxins (toxic substances)”; “poisonous”, this word started to have figurative meanings which characterize relations in business: toksichnyy rukovoditel’ (toxic boss), toksichnye kollegi (toxic colleagues), toksichnye rabotniki (toxic workers), toksichnye delovye otnosheniya (toxic business relationships). All this allows us to talk about extension of the semantic weight of the word “toxic”. The definition of “toxic” is increasingly related to the notion of communication.

The analysis of an extensive body of literature shows that toxic communication is considered mainly from the standpoint of the psychological characteristics of a person, his or her behavioural reactions [Lipman-Blumen, 2006; Kets de Vries, Balazs, 2011; Kets de Vries, 2014; Morais, Randsley de Moura, 2018; Eissa, Wyland, 2018; Ten Brinke, Lee, Carney, 2019]. Researchers examined the effects of the derogatory group labels on the behavioural responses [Carnaghi, Maas, 2006]. They studied destructive communication in various social groups [Glenn, Chow, 2002; Munn, 2020], analysed the use of derogatory language towards groups of people [Carnaghi, Maas, 2007; Fasoli, Carnaghi, Paladino, 2015; Walton, Banaji, 2004] conflict-initiating factors and management styles in intergenerational relationships in and out of family context [Wiebe, Zhang, 2017], thoroughly explored the problems of social pain, which is the pain caused by the threatened or actual loss of social connections [Eisenberger, 2010; Riva, Brambilla, Vaes, 2016]. The problems discussed are focused upon the dependence between the language style matching (LSM), subjective perception of the interaction quality (perceived responsiveness and affect) and the behaviour of a romantic partner in two communicative contexts: conflict and social support [Bowen, Winczewski, Collins, 2016]. Experts show keen interest in the research of various sides of communication [Moscatelli, Prati, Rubini, 2019; Cavazza, Guidetti, 2018], the specifics of semantics and pragmatics of slurs [Hedger, 2013; Croom, 2014; Anderson, Lepore, 2013], and search for ways to analyze online hate speech and toxic communication [Gagliardone, Pohjonen, Orton-Johnson, 2022].

There are scientific advancements in the field of social neuroscience, which prove that the participants who were exposed to threat demonstrated a consistent increase in their cortisol levels indicative of a stress response, compared to those who were not exposed to a threat. These findings suggest that group-based threats do indeed incur a stress related physiological response [Sampasivam et al., 2018].

All these studies form a good theoretical basis to explore toxic communication in the working environment and its consequences for employees.

Multi-stage, extensive research aimed at understanding the modern forms of employment show “that people do in fact deem poor worker treatment (e.g., asking employees to do demeaning tasks that are irrelevant to their job description, asking employees to work extra hours without pay) as more legitimate when workers are presumed to be ‘passionate’ about their work. Taken together, these studies suggest that although passion may seem like a positive attribute to assume in others, it can also license poor and exploitative worker treatment” [Kim et al., 2020, p. 121].

Some papers examine the problems of leaders possessing various levels of charisma concluding that “leaders low on charisma are less effective because they lack strategic behavior; highly charismatic leaders are less effective because they lack operational behavior” [Vergauwe et al., 2018, p. 110].

In addition to that, there is research dedicated to so-called upward bullying of managers. The results of some qualitative study design suggest that “several factors could be linked to the bullying: being new in the managerial position; lack of clarity about roles and expectations; taking over a work group with ongoing conflicts; reorganizations. The bullying usually lasted for quite some time. Factors that allowed the bullying to continue were passive bystanders and the bullies receiving support from higher management. The managers in this study adopted a variety of problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies. However, in the end most chose to leave the organization” [Björklund et al., 2019]. However, bullying most often comes from destructive bosses and managers.

Toxic communication, particularly in the speech of bosses or managers, is considered mainly from the standpoint of linguistic mechanisms of non-ecological speech behaviour, among which there are violations of business etiquette, the presence of verbal forms of intentional confusion, and the formation of psychological dependence of subordinates on their superiors [Patterson et al., 2018]. In general, researchers have been studying the problem of toxic communication for two decades already [Frost, 2003; Appelbaum, Roy-Girard, 2007, Sheth, Shalin, Kursuncu, 2021]. The studies of Englishspeaking authors show that about one-fifth of American workers consider that is their work environment toxic. Besides, it is estimated that a single toxic employee can cost a company more than $12,000 [Housman, Minor, 2015]. The toxicity can affect the performance of other employees as well: 38 percent of employees say they decrease the quality of their work in a toxic work environment, 25 percent say they have taken out their frustration on customers, and 12 percent have simply left their jobs because of a toxic workplace. As noted by experts in the field of linguistics of emotions, verbalized emotions have a significant impact on the psychological and physical health of a person [Shakhovsky, 2014].

A number of scientific works were devoted to the study of this phenomenon in the theory and practice of interpersonal and business communication [Too, Harvey, 2012], personnel management [Branch, Ramsay, Barker, 2007; Erickson et al., 2015], and also in connection with the problems solved by ecolinguistics [Shamne, Shovgenin, 2010; Fill, 2018; Haugen, 1972; Steffensen, Fill, 2013; Stibbe, 2020; Chen, 2016] and linguoecology [Skovorodnikov, 2019]. The papers of Russian scientists consider linguistic

РАЗВИТИЕ И ФУНКЦИОНИРОВАНИЕ characteristics of speech communication of the so-called toxic leader [Ionova, 2018, p. 1]. Researchers point out rightly that “toxic communications at the workplace can negatively impact overall job satisfaction and are often subtle, hidden, or demonstrate human biases” [Bhat et al., 2021, p. 2017].

Detailed studies on the impact of toxic communication patterns in industry on management practices were also carried out on the example of Russian enterprises [Fedorova, Menshikova, 2014]. However, in the Russian-language scientific literature, the problems of toxic communication in the workplace, despite their importance, are not given enough attention, which underlines the relevance of research on toxic Russian-language communication in industry due to practical reasons.

The object of this study is toxic communication in industry which means the forms of destructive communication in the production sector that violate ethical standards, incite people to dissatisfaction and anxiety, reduce motivation and urge the intention to quit their jobs. In this study, we analyse main areas of toxic Russian-language communication in the production sector, as well as speech markers of toxicity (negative affectives and connotatives) [Shakhovsky, 1994; Shakhovsky, 2019], whose widespread use can reduce the effectiveness of communication.

Materials and methods

We used former employees’ comments about Russian chemical enterprises posted on the website work-info.name (Work-Info) as the material of our study. We analysed what reasons had forced these employees to leave their jobs and what negative characteristics of enterprises were emphasized in the comments. A total of 322 comments were studied.

In addition, the employees of two organizations – a chemical enterprise and a healthcare institution – were asked to complete an anonymous questionnaire. The choice of organizations that differ in the scope of activity was determined by the research hypothesis which consisted in the fact that production workers are more likely to encounter toxic communication than employees of a healthcare institution. The sample consisted of 25 employees of the chemical

РУССКОГО ЯЗЫКА

enterprise and 30 employees of the healthcare institution. All the respondents received the questionnaires with the following questions:

Have you ever felt insecure and frightened in your workplace?

Have you ever felt intimidated by your boss?

Have you ever been irritated when dealing with your boss?

Have you witnessed conflicts between your boss and employees?

Have you been involved in conflicts with your boss?

Have you witnessed conflicts between employees?

Have you been involved in conflicts with employees?

Have you been insulted by your supervisor?

Have you been insulted by your colleagues?

Have you been persecuted because of your ethnicity?

Have you been persecuted because of your religious beliefs?

Have you been persecuted because of your sexual orientation?

Have you been persecuted because of your appearance, your body type?

The criterion for dividing the subjects into those who “had an effect” and those who “had no effect” was a sign of toxic communication presence (the fact of conflicting speech behaviour or the fact of stress in the workplace). Focusing on the hypothesis, we accepted that there was an “effect” when the respondent confirmed the toxicity of communication (60% or more of the answers were “yes”), and that there was “no effect” when the respondent did not note the toxicity of communication (60% or more of the answers were “no”).

In this study, the Fisher angular transformation method was employed to benefit from the opportunity to compare small samples with high accuracy of calculations. The calculation was carried out according to the formula:

n ' n

ф * = ( ф 1 - Ф 2 ) • —1--- 2-

\ П 1 + n 2

where: φ1 is the angle corresponding to a larger percentage; φ2 is the angle corresponding to a smaller percentage; n 1 is the number of observations in the first sample; n 2 is the number of observations in the second sample.

Having examined former employees’ feedback about Russian chemical enterprises and the anonymous questionnaires, we found that, speaking of the examples of toxic communication at work, employees of Russian companies often noted rudeness and violent language of their bosses and colleagues, but they expressed practically no complaints about bullying related to discrimination by sex, age, ethnicity, religion, etc. Following this observation, we arranged a Likert scale survey (rating scale method) to identify the focuses of toxicity and their possible dependence on the employee’s attribution to one of the ranges (boss, manager, employee) among the bosses, managers, and employees of a chemical enterprise (separately for each of these groups). As is known, Likert’s methodology uses a scale which allows revealing the respondents’ attitude to the problem in question where they express their agreement or disagreement with the proposed statement. There are various modifications of measurement scales which include two to seven evaluation points. We used the classic scale including five points: disagree – 1; partly disagree – 2; neutral – 3; partly agree – 4; agree – 5. To identify the factors that influence toxic communication, we performed further statistical processing of the data which included single-factor and multi-factor analysis of variance performed with the standard Excel tools.

Results and discussion

The results of processing the respondents’ questionnaires using the Fisher angular transformation method are shown in Table 1.

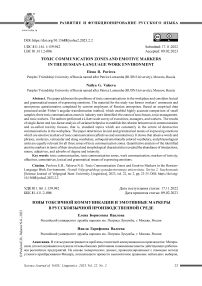

For clarity, let as draw the Fisher significance axis (Fig. 1).

As can be seen from the data in Table 1 and Figure 1, the obtained empirical value of φ * is in the area of insignificance. Therefore, we reject the hypothesis about the dependence between toxic communication in industry and the scope of the organization’s activity. In other words, any organization can become toxic. Our conclusion is backed by other pieces of research, (e.g.: [Björklund et al., 2019]). The analysis of the former employees’ comments of the Russian chemical enterprises shows that at least three zones of toxic communication can be distinguished: toxic boss; toxic workers; toxic management. The main markers of toxicity expressing emotions and possessing denotative emotionality are negative affectives: abusive words and phrases, invectives. In terms of structural-morphological classification, affectives are represented by interjections, nouns, phrasemes, and fixed noun + adjective expressions. The status of optional emotivity is represented by speech unit connotations. The group of connotatives can include word-formative derivatives with affixes of emotive-subjective evaluation, word-formative (semantic) derivatives of various types, zoolexics, vernacular and slang vocabulary, colloquial emotionally colored vocabulary, phraseological units, adjectives, adverbs of degree and intensity. In toxic communication, the status of optional emotionality can be illustrated by the following typical examples: chelovechishka (spineless human); voryuga (crook); direktrisa (directress) colloquial, disapproving of a female chief executive; zveryuga (brute) about the boss, sil’no-presil’no (very very), poedom est (rap (someone) over the knuckles). The optional emotionality is regularly realized by the tropeized zoolexemes where the

Table 1. Calculation of the Fisher criterion when comparing two groups of employees questioned

|

Group |

“There is an effect” Number of test subjects |

p |

“There is no effect” Number of test subjects |

p |

Total |

|

1 |

19 (76%) |

p < 0,05 |

6 (24%) |

p < 0,01 |

25 (100%) |

|

2 |

22 (73,3%) |

8 (26,7%) |

30 (100%) |

||

|

φ*EM= |

0,229 |

||||

Fig. 1. The Fisher significance axis

semantic structure is reduced to a symbolic component, expressing the social emotion of evaluating such qualities as greed, rapacity, cruelty, dumbness, stupidity and stubbornness: shakal (jackal), baran (ram), ovtsa (sheep), osyol (donkey) about the colleagues. In zoolexems, the emotion of evaluating such features of a person’s appearance as obesity/thinness ( slon/slonikha (elephant), korova (cow), vobla (roach), selyodka (herring)) or unattractiveness ( obezyana (monkey)), untidiness ( svinya (pig)) is also metaphorically actualized.

Table 2 shows the identified toxic communication zones with illustrative typical examples from the comments analysed. The markers of toxicity are in italics.

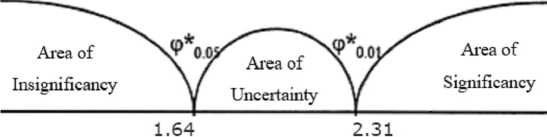

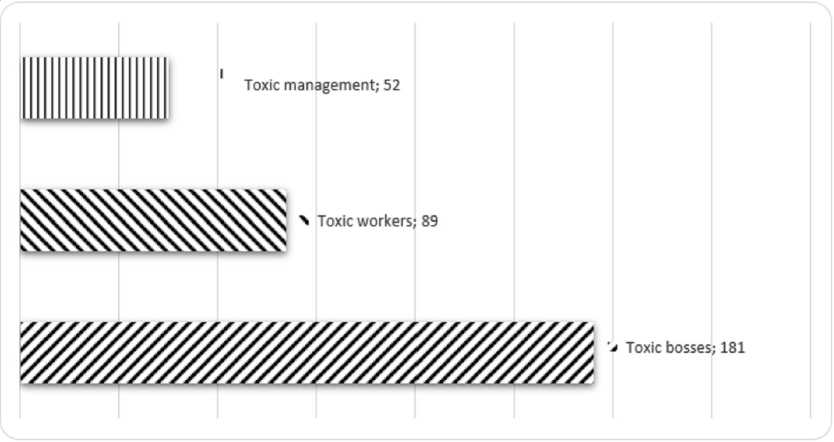

All comments given as illustrative material were posted in Russian. In the paper (Table 2) we provide our own translations of these comments into English. As shown in Table 2, the Communication of a toxic boss zone is characterized by aggressive speech actions, violations of business etiquette and destructive activities which incite subordinates to react in a negative manner and even quit the job. The Communication of toxic workers zone can be divided into two sectors – the sector of toxic actors who poison their colleagues with destructive communication and the sector of toxic recipients who constantly experience colleagues’ violent communication. Even though toxic employees-actors are often high performers, eventual results of their work are negative due to the destructive effect on colleagues causing economic harm to the production or organization. Thus, toxic employees-recipients experience a double toxic pressure – from their boss and co-workers, which leads to a decrease in their performance, emotional burnout and, in general, to constant staff turnover. The Toxic management communications zone reflects the destructive component of management communication in industry, which is characterized by intentional confusion, the absence of feedback, and weak corporate culture. Figure 2 shows the zones of toxic communication in industry according to the number of the negative comments analysed.

Table 2. Zones of toxic communication

|

Zone of toxic communication |

Comment examples |

|

Communication of a toxic boss |

Just an ordinary energy vampire ... sucks out vitality and energy from the people!!! yells at everybody no matter what they do; he doesn’t filter what he says when talking to his subordinates, humiliates them; Gosh! He takes out his rage and negativity on people with such fury that they get sick, go to hospital with a heart attack; throws temper tantrums through the office; I went to work... and two days later it started!!!! The directress speaks with burning hatred of her subordinates calling them fat pigs , lazy critters , etc.; The director and his deputy are simply crooks . The head of the department... does not know how to talk to people. For her, they’re cattle , expendable ! Ohhhh ... I’ve never written comments, but the management here is just trash |

|

Communication of toxic workers |

Employees look like watch dogs ; ill-mannered; gossips and envious people are everywhere; employees are intimidated and lack initiative; people working there are cowed and slavelike, they twitch nervously when looked at; they are a herd of confused cattle ; in some departments there are Sharks working who rap everyone over the knuckles and ease out any potential employee who can take their place. Of course, because they are all over 55, and they themselves do not want to work and do not give others; ratted on me to the directress , a dry old roach |

|

Toxic management communications |

They hold three meetings a day, talk bullshit , and then the secretary calls up and asks who exactly are tasked and what the tasks are; the meeting can last an hour or two with a large number of staff, but for the most part, the only thing you can learn about in such meetings is that someone from our staff is a moron or an idiot ; no living corporate culture; they don’t introduce you to anyone, no one gets you acquainted with other employees, no one greets you. The territorial manager is a jackal , he is always nosing about , looking for any kind of a clue to deprive a person of his salary. You have to work like a donkey to reach the targets and no one cares if you make it or not, the targets must be reached or the shift manager will eat you up ; Oh, gosh! This is really some kind of sanctuary for fearless idiots |

As shown in Figure 2, the zones of the toxic bosses and toxic colleagues have the greatest impact on workers. In addition, all the zones we have identified tend to overlap each other, thus creating the strongest pressure of toxic communication on the employee (Fig. 3).

As was already mentioned, the detailed study of the comment about organizations and the toxic communication zones revealed the need to find the toxicity focuses and their potential dependencies on the employee’s attribution to one of the ranges (boss, manager, employee) among the employees of a chemical enterprise (separately for each of the distinguished groups). To solve this problem, we organized a Likert scale survey. The respondents in each group were asked to evaluate the degree of their agreement or disagreement with each of the following statements. Tables 3 to 5 show examples of typical answers given by the respondents in each employee group.

As can be seen from the typical answers, the focus of toxic communication gravitates towards such features as stupidity or excessive emotionality; the respondents reacted less to ethnicity, religious beliefs, and sexual orientation. In the Employee group, a strong irritating factor was the specific of someone’s body type and appearance. To verify statistical significance of the identified dependencies, we performed the analysis of variance.

Fig. 2. Quantitative data reflecting the distribution of toxic communication zones

Toxic bosses

Fig. 3. Overlapping of toxic communication zones in industry

Table 3. Typical Likert scale answers for the boss group

|

Statement |

Strongly disagree (1) |

Mostly disagree (2) |

Neutral (3) |

Mostly agree (4) |

Strongly agree (5) |

|

Employee’s stupidity irritates me |

– |

– |

– |

– |

× |

|

Intemperance and the lack of culture irritate me |

– |

– |

– |

× |

– |

|

The lack of professional skills irritates me |

– |

– |

– |

– |

× |

|

People whose ethnicity is other than the titular nation irritate me |

– |

× |

– |

– |

– |

|

People whose religious beliefs are other than the titular religion irritate me |

– |

× |

– |

– |

– |

|

People with non-standard sexual orientation irritate me |

– |

– |

× |

– |

– |

|

Specific features of people’s body and appearance irritate me |

– |

× |

– |

– |

– |

|

The fact that the team is mostly female/ male irritates me |

– |

– |

× |

– |

– |

Table 4. Typical Likert scale answers for the manager group

|

Statement |

Strongly disagree (1) |

Mostly disagree (2) |

Neutral (3) |

Mostly agree (4) |

Strongly agree (5) |

|

Employee’s stupidity irritates me |

– |

– |

– |

– |

× |

|

Intemperance and the lack of culture irritate me |

– |

– |

– |

– |

× |

|

The lack of professional skills irritates me |

– |

– |

– |

× |

– |

|

People whose ethnicity is other than the titular nation irritate me |

– |

× |

– |

– |

– |

|

People whose religious beliefs are other than the titular religion irritate me |

– |

× |

– |

– |

– |

|

People with non-standard sexual orientation irritate me |

– |

– |

– |

× |

– |

|

Specific features of people’s body and appearance irritate me |

– |

– |

– |

– |

× |

|

The fact that the team is mostly female/male irritates me |

– |

– |

× |

– |

– |

Table 5. Typical Likert scale answers for the employee group

|

Statement |

Strongly disagree (1) |

Mostly disagree (2) |

Neutral (3) |

Mostly agree (4) |

Strongly agree (5) |

|

My colleagues’ stupidity irritates me |

– |

– |

– |

– |

× |

|

Intemperance and the lack of culture irritate me |

– |

– |

– |

× |

– |

|

The lack of professional skills irritates me |

– |

– |

– |

× |

– |

|

People whose ethnicity is other than the titular nation irritate me |

– |

– |

× |

– |

– |

|

People whose religious beliefs are other than the titular religion irritate me |

– |

– |

× |

– |

– |

|

People with non-standard sexual orientation irritate me |

– |

– |

– |

× |

– |

|

Specific features of people’s body and appearance irritate me |

– |

– |

– |

– |

× |

|

The fact that the team is mostly female/male irritates me |

– |

– |

– |

– |

× |

At the first stage of our statistical analysis, we planned to find out whether toxic communication in the organization generally depends on the boss, manager, and employee communication zones. The influence of the communication zone on the toxic communication was determined by means of the Excel single-factor ANOVA tool. We used the rates obtained by processing the Likert scale questionnaires as quantitative data.

In Table 6: SS are the sums of squares; df is the degree of freedom; MS are mean squares; F is the calculated value of Fisher’s F -criterion; P is the value.

If P < α = 0.05, then the factor in question is statistically significant. In our case, P > α = 0.05 which evidences the absence of a statistically significant dependence. As F = 0.78 does not exceed the upper critical value F = 1.78, F < Fcr , that means that there are no significant differences between the groups, therefore, toxic communication does not depend on the boss, manager, or employee zone.

To verify the results with the Excel two-factor ANOVA tool, in addition to the communication zone factor, we used the topic toxicity focus factor. The topic toxicity focus is understood as an enduring topic identified with the Likert scale, which appears in toxic speech: lack of intelligence, lack of self-control and culture, lack of professional skills, appearance (body type specifics), non-standard sexual orientation, etc. Table 7 summarizes our analysis of variance.

Below is the analysis of the obtained results:

– the calculated value of the F -criterion for the communication zone factor is 1.67. The critical value of the F -criterion is 1.79, which means that the influence of this factor is insignificant;

– the calculated value of the F -criterion for the topic toxicity factor is 17.76. The critical value of the F -criterion is 2.10, which means that the influence of this factor is significant.

The obtained statistically significant results of the two-factor ANOVA are in line with the data resulting from the single-factor ANOVA, which proves that the toxic communication does not depend on the employee range, or the boss, manager, or employee zone. In other words, it exists in all these zones.

The obtained statistically significant results of the two-factor analysis of variance are in line with the data obtained using the Likert scale; they prove the statistically significant correlation between the toxic communication and the most enduring toxic (topical) focuses. One of the ways to overcome the destructive effects of toxic communication is to foster a healthy corporate speech culture that may weaken “communicative wars of all against all” in the workplace.

Conclusions

Therefore, the empirical study has not proved the expected dependence between the toxic communication and the organization’s area of activity and its goals. Although the percentage of those who encountered toxic communication at the chemical enterprise was higher than at the healthcare institution (76% of respondents vs 73.3%), these differences in percentages are not statistically significant. Verification of these samples using the Fisher criterion showed the absence of statistical superiority of one sample over another. The obtained empirical value φ*EM = 0.229 is less than the established critical value of statistical significance of 1.64 and is

Table 6. Results of the single-factor analysis of variance

|

Analysis of variance |

||||||

|

Source of variance |

SS |

df |

MS |

F |

P-Value |

F critical |

|

Between the groups |

16.16667 |

14 |

1.154762 |

0.78926 |

0.678622 |

1.787079 |

|

Intra-group |

153.625 |

105 |

1.463095 |

– |

– |

– |

|

Total |

169.7917 |

119 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Table 7. Results of the two-factor analysis of variance

|

Analysis of variance |

||||||

|

Source of variance |

SS |

df |

MS |

F |

P-value |

F critical |

|

Lines |

16,16667 |

14 |

1,154762 |

1,67159 |

0,073984 |

1,793981 |

|

Columns |

85,925 |

7 |

12,275 |

17,76883 |

4,9E-15 |

2,104448 |

|

Error |

67,7 |

98 |

0,690816 |

– |

– |

– |

outside the area of significance. Among the markers of toxicity, the employees of the chemical enterprise and health care institution named abusive words and phrases ( tupitsy (nitwits), tupye tvari (stupid brutes), nepuganye idioty (fearless idiots), bydlo (cattle), gadyushnik (shithole), pomoyka (trash heap)), zoolexemes ( kollegi – zmei v zmeinom logove (colleagues are like vipers in their nest); administratory – sobaki tsepnye (managers are like watchdog)), colloquial expressions ( organizovannost’ na nule (management is at zero)); phraseological units ( polny nol’ (complete zero); nol’ bez palochki (an empty zero), vyzhaty limon (squeezed lemon)).

The analysis of former employees’ feedback about their employers shows that there are at least three zones of toxic communication in the industry (toxic boss, toxic management, toxic employees), which tend to overlap, thereby creating additional risks for the organization’s performance. However, no dependence has been revealed between toxic communication and key representatives of the identified zones, that is, bosses, managers, and employees (the obtained criterion F = 0.78 does not exceed the upper critical value Fcr = 1.78, F < Fcr ). In other words, toxic communication proliferates in each of the identified zones.

The Likert scale analysis of the respondent’s questionnaires and further statistical analysis ( F = 17,76, F > Fcr ) also show that in Russian companies there is a strong correlation between toxic communication and so-called toxicity focuses – standard topics – which are constantly in the centre of destructive communication. These topics are lack of intelligence, lack of self-control and culture, lack of professional skills, appearance (body types), non-standard sexual orientation, etc.

Verbalization of zones of toxic communication zones is carried out by means of various linguistic levels. At the lexical level, the main markers of toxicity in work communication are negative emotives and affectives that are abusive words, phrasemes, invectives, and connotatives including word-formative derivatives with affixes of emotive-subjective evaluation, zoolexics, vernacular and slang vocabulary, colloquial emotionally colored vocabulary, and phraseological units.

At the grammatical level, affectives are represented by interjections, nouns, phrasemes, and fixed noun + adjective expressions, emotional and evaluative adjectives and adverbs of degree and intensity; connotatives are limited to nouns in the material studied.

So, we can say that promoting corporate speech culture targeted against the toxicity focuses that we have identified is the key method of minimizing toxic communication risks in the Russian industry.

Список литературы Toxic communication zones and emotive markers in the Russian-language work environment

- Anderson L., Lepore E., 2013. What Did You Call Me? Slurs as Prohibited Words. Analytic Philosophy, vol. 54, no. 3, pp. 350-363. DOI: 10.1111/ phib.12023

- Appelbaum S.H., Roy-Girard D., 2007. Toxins in the Workplace: Affect on Organizations and Employees Corporate Governance. International Journal of Business in Society, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1728. DOI: 10.1108/14720700710727087

- Bhat M.M., Hosseini S., Awadallah A.H., Bennett P., Li W., 2021. Say 'YES' to Positivity: Detecting Toxic Language in Workplace Communications. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021, pp. 2017-2029. DOI: 10.18653/v1/2021 .findings-emnlp. 173

- Bjorklund C., Hellman T., Jensen I., Ákerblom C., Bjork Bramderg E., 2019. Workplace Bullying as Experienced by Managers and How They Cope: A Qualitative Study of Swedish Managers. Int J Environ Public Health, vol. 16, no. 23, art. 4693. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph16234693. URL: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/16/23/4693

- Bowen J., Winczewski L.A., Collins N.L., 2016. Language Style Matching in Romantic Partners' Conflict and Support Interactions. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 263-286. DOI: 10.1177/0261927X16666308

- Branch S., Ramsay S., Barker M., 2007. Managers in the Firing Line: Contributing Factors to Workplace Bullying by Staff - An Interview Study. Journal of Management & Organization, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 264-281. DOI: 10.1017/S1833367200003734

- Carnaghi A., Maas A., 2006. The Effects of the Derogatory Group Labels on the Behavioral Responses. Psicologia Sociale, vol. 1, pp. 121-132. DOI: 10.1482/21504

- Carnaghi A., Maass A., 2007. In-Group and Out-Group Perspectives in the Use of Derogatory Group Label: Gay Versus Fag. Journal ofLanguage and Social Psychology, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 142-156. DOI: 10.1177/0261927X07300077

- Cavazza N., Guidetti M., 2018. Captatio Benevolentiae: Potential Risks and Benefits of Flattering the Audience in a Public Political Speech. Journal of Language and Social

- Psychology, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 706-720. DOI: 10.1177/0261927X18800132

- Chen S., 2016. Language and Ecology: A Content Analysis of Ecolinguistics as an Emerging Research Field. Ampersand, vol. 3, pp. 108-116. DOI: 10.1016/j.amper.2016.06.002

- Croom A.M., 2014. The Semantics of Slurs: A Refutation of Pure Expressivism. Language Sciences, vol. 41, pp. 227-242. DOI:10.1016/j. langsci.2013.07.003

- Eisenberger N.I., 2012. The Pain of Social Disconnection: Examining the Shared Neural Underpinnings of Physical and Social Pain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, vol. 13, pp. 421-434. DOI: 10.1038/nrn3231

- Eissa G., Wyland R., 2018. Work-Family Conflict and Hindrance Stress as Antecedents of Social Undermining: Does Ethical Leadership Matter? Applied Psychology, vol. 67, no. 4, pp. 645-654. DOI: 10.1111/apps.12149

- Erickson A., Shaw B., Murray J., Branch S., 2015. Destructive Leadership. Organizational Dynamics, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 266-272. DOI: 10.1016/ j.orgdyn.2015.09.003

- Fasoli F., Carnaghi A., Paladino M.P., 2015. Social Acceptability of Sexist Derogatory and Sexist Objectifying Slurs Across Contexts. Language Sciences, vol. 52, pp. 98-107. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2015.03.003

- Fedorova A., Menshikova M., 2014. Social Pollution Factors and Their Influence on Psychosocial Wellbeing at Work. International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conferences on Social Sciences and Arts - SGEM2014 (Bulgaria, Albena, September 1-10, 2014), vol. 2, pp. 839-846. DOI: 10.5593/sgemsocial2014/ B12/S2.107

- Fill A., 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Ecolinguistics. London, Routledge. 476 p.

- Frost P.J., 2003. Toxic Emotions at Work: How Compassionate Managers Handle Pain and Conflict. Cambridge, MA, Harvard Business School Press. 256 p.

- Gagliardone I., Pohjonen M., Orton-Johnson K., eds., 2022. How to Analyze Online Hate Speech and Toxic Communication. London, SAGE Publications, Ltd. DOI: 10.4135/9781529609721

- Glenn C.V., Chow P., 2002. Measurement of Attitudes Toward Obese People Among a Canadian Sample of Men and Women. Psychological Reports, vol. 91, no. 2, pp. 627-640. DOI: 10.2466/ pr0.2002.91.2.627

- Haugen E., 1972. The Ecology of Language. Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press. 366 p.

- Hedger J.A., 2013. Meaning and Racial Slurs: Derogatory Epithets and the Semantics/Pragmatics Interface. Language & Communication, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 205-213. DOI: 10.1016/j.langcom.2013.04.004 Housman M., Minor D., 2015. Toxic Workers. Harvard, Harvard Business School. 38 p.

- Ionova S.V., 2018. Toksichnyy rukovoditel: lingvoekologiya rechevogo povedeniya [Toxic Head: Linguoecology of Verbal Behavior]. Ekologiya yazyka i kommunikativnaya praktika [Ecology of Language and Communicative Practice], vol. 4, pp. 1-12. DOI: 10.17516/2311-3499-033

- Kets de Vries M., 2014. Coaching the Toxic Leader: Four Pathologies That Can Hobble an Executive and Bring Misery to the Workplace - And What to Do About Them. Harvard Business Review, vol. 92, no. 4, pp. 100-109.

- Kets de Vries M., Balazs K., 2011. The Shadow Side of Leadership. The Sage Handbook of Leadership. London, Sage, pp. 380-392.

- Kim J.Y., Campbell T.H., Shepherd S., Kay A.C., 2020. Understanding Contemporary Forms of Exploitation: Attributions of Passion Serve to Legitimize the Poor Treatment of Workers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 118, no. 1, pp. 121-148. DOI: 10.1037/pspi0000190

- Lipman-Blumen J., 2006. The Allure of Toxic Leaders: Why We Follow Destructive Bosses and Corrupt Politicians - And How We Can Survive Them. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 320 p.

- McKirdy E., 2018. Toxic: Oxford Dictionaries Sums Up the Mood of 2018 with Word of the Year. URL: https://www.ksl.com/article/46427887/ toxic-oxford-dictionaries-sums-up-the-mood-of-2018-with-word-of-the-year

- Morais C., Randsley de Moura G., 2018. The Psychology of Ethical Leadership in Organisations. Palgrave MacMillan. 96 p. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-02324-9

- Moscatelli S., Prati F., Rubini M., 2019. If You Criticize Us, Do It in Concrete Terms: Linguistic Abstraction as a Moderator of the Intergroup Sensitivity Effect. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, vol. 38, no. 5-6, pp. 680-705. DOI: 10.1177/0261927X19864686

- Munn L., 2020. Angry by Design: Toxic Communication and Technical Architectures. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, vol. 7, no. 53, pp. 1-11. DOI: 10.1057/s41599-020-00550-7

- Patterson E., Branch S., Barker M., Ramsay S., 2018. Playing with Power: Examinations of Types of Power Used by Staff Members in Workplace Bullying - A Qualitative Interview Study. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management an International Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 32-52. DOI: 10.1108/QROM-10-2016-1441

- Riva P., Brambilla M., Vaes J., 2016. Bad Guys Suffer Less (Social Pain): Moral Status Influences Judgements of Others' Social Suffering. British Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 88-108. DOI: 10.1111/bjso. 12114

- Sampasivam S., Collins K.A., Bielajew C., Clément R., 2018. Intergroup Threat and the Linguistic Intergroup Bias: A Stress Biomarker Study. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 632-655. DOI: 10.1177/ 0261927X18799807

- Sheth A., Shalin VL., Kursuncu U., 2021. Defining and Detecting Toxicity on Social Media: Context and Knowledge Are Key. Neurocomputing, vol. 490, pp. 312-318. DOI: 10.1016/j.neucom.2021.11.095

- Shamne N.L., Shovgenin A.N., 2010. Teoreticheskie osnovy postroeniya algoritma ekolingvisticheskogo monitoringa [Theoretical Grounds of Algorithm Design for Ecolinguistic Monitoring]. Vestnik Volgogradskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Seriya 2, Yazykoznanie [Science Journal of Volgograd State University. Linguistic], vol. 9, no. 2 (12), pp. 153-161. Shakhovsky V.I., 2019. Kategorizatsiya emotsiy v leksiko-semanticheskoy sisteme yazyka [Categorization of Emotions in the Lexico-Semantic System of Language]. Moscow, URSS Publ. 206 p.

- Shakhovsky V.I., 2014. Emotivnaya lingvoekologiya: kompleksnyy podkhod k izucheniyu yazyka, rechevoy deyatelnosti i cheloveka [Emotive Lingua-Ecology: the Complex Approach to the Study of Language, Speech Activity, and a Human Being]. Voprosy psikholingvistiki [Journal of Psycholinguistics], vol. 19, pp. 13-21.

- Shakhovsky V.I., 1994. Tipy znacheniy emotivnoy leksiki [Types of Emotive Vocabulary Meanings]. Voprosy yazykoznaniya [Topics in the Study of Language], vol. 1, pp. 20-25.

- Steffensen S.V, Fill A., 2013. Ecolinguistics: The State of the Art and Future Horizons. Language Sciences, vol. 41, pp. 6-25. DOI: 10.1016/j.langsci.2013.08.003

- Skovorodnikov A.P., 2019. O nekotorykh nereshennykh voprosakh teorii lingvoekologii [On Some Unanswered Questions of the Linguo-Ecological Theory]. Politicheskaya lingvistika [Political Linguistics], vol. 5, no. 77, pp. 12-25. DOI: 10.26170/pl19-05-1

- Stibbe A., 2020. Ecolinguistics: Language, Ecology, and the Stories We Live by. London, Routledge. 260 p. DOI: 10.4324/9780367855512

- Ten Brinke L., Lee J.J., Carney D.R., 2019. Different Physiological Reactions When Observing Lies Versus Truths: Initial Evidence and an Intervention to Enhance Accuracy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 117, no. 3, pp. 560-578. DOI: 10.1037/pspi0000175

- Too L., Harvey M., 2012. "TOXIC" Workplaces: The Negative Interface Between the Physical and Social Environments. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 171-181. DOI: 10.1108/ 14630011211285834

- Vergauwe J., Wille B., Hofmans J., Kaiser R.B., De Fruyt F., 2018. The Double-Edged Sword of Leader Charisma: Understanding the Curvilinear Relationship Between Charismatic Personality and Leader Effectiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 114, no. 1, pp. 110-130. DOI: 10.1037/pspp0000147

- Walton G.M., Banaji M.R., 2004. Being What You Say: The Effect of Essentialist Linguistic Labels on Preferences. Social Cognition, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 193-213. DOI: 10.1521/soco.22.2.193.35463

- Wiebe W.T., Zhang Y.B., 2017. Conflict Initiating Factors and Management Styles In Family And Nonfamily Intergenerational Relationships: Young Adults' Retrospective Written Accounts. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 368-379. DOI: 10.1177/0261927X16660829