A Hybrid SWARA-NWA Framework for Evaluating AI-Based Image Recognition Algorithms in Educational Technology Applications

Автор: Nikola Gligorijević, Sonja Popović, Vojkan Nikolić, Dejan Viduka, Stefan Popović

Журнал: International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education @ijcrsee

Рубрика: Original research

Статья в выпуске: 3 vol.13, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

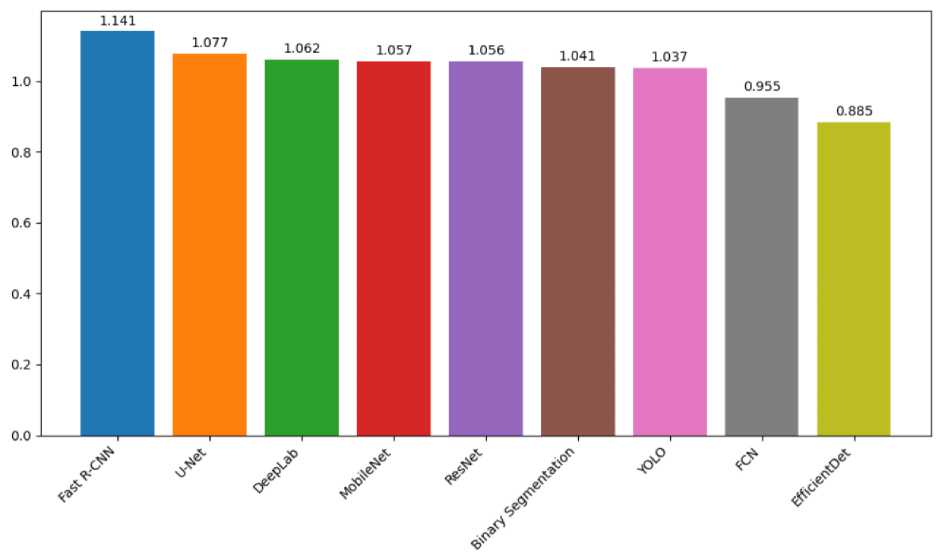

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and computer vision technologies are increasingly integrated into educational environments through intelligent tutoring systems, gesture-based learning, facial expression analysis, and automated evaluation tools. However, selecting the most appropriate image recognition algorithms for educational applications remains a challenge due to varying requirements regarding speed, accuracy, hardware compatibility, and usability in dynamic classroom conditions.This paper proposes a hybrid multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) model based on the Step-wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (SWARA) and Net Worth Analysis (NWA) methods to evaluate and rank nine widely used AI-based visual recognition algorithms. The evaluation is conducted using five education-relevant criteria: processing speed, recognition accuracy, robustness to classroom noise, compatibility with low-end devices, and energy efficiency. Expert assessments from the field of educational technology were used to derive weight coefficients and evaluate algorithm performance.The results show that Fast R-CNN achieved the highest overall score (1.141), followed by U-Net (1.077) and DeepLab (1.062), indicating their suitability for real-time and resource-constrained EdTech environments. Algorithms such as MobileNet (1.057) and YOLO (1.037) also demonstrated balanced performance, making them viable for mobile or moderately demanding educational scenarios. The proposed model offers a structured and transparent decision-support framework that can assist researchers and practitioners in selecting optimal AI algorithms for diverse educational applications.

Educational technology, Artificial intelligence, Computer vision, Multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) and Algorithm evaluation

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170211410

IDR: 170211410 | УДК: 37.091.39:004.85 | DOI: 10.23947/2334-8496-2025-13-3-719-735

Текст научной статьи A Hybrid SWARA-NWA Framework for Evaluating AI-Based Image Recognition Algorithms in Educational Technology Applications

In the past decade, artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have become a key component of the educational sector, enabling personalized instruction, automated assessment, student behavior detection, and real-time learning analytics ( Rane et al., 2023 ; Chen et al., 2020 ; Li et al., 2023 ). A particularly significant role in this development is played by computer vision algorithms, which are applied in handwriting recognition, facial expression analysis, student attendance tracking, and gesture-based interactive learning ( Zabulis, Baltzakis and Argyros, 2009 ). However, these algorithms are predominantly developed for industrial applications, and their direct use in education is often hindered by requirements such as low hardware demand, interpretability, and energy efficiency. Modern educational institutions, especially those implementing smart classrooms or mobile EdTech platforms, face the challenge of selecting AI algorithms that are both pedagogically appropriate and technically feasible ( Dimitriadou and Lanitis, 2023 ).

In the context of Serbia’s ongoing digital educational reform, these challenges gain further com-

© 2025 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license .

plexity. The National Education Development Strategy of the Republic of Serbia until 2030 envisions an intensive digitalization of the teaching process, with an emphasis on improving digital competencies of teachers and students, as well as the integration of digital tools into everyday classroom practice. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the mandatory use of learning management systems (LMS) at the school level, marked the beginning of a systemic digital transformation in the education sector ( Ibrahim et al., 2020 ). In this direction, the e-Dnevnik platform has been widely adopted for electronic documentation of pedagogical processes, while the Unified Information System of Education (JISP) has become a crucial tool for monitoring and analyzing educational data at the national level ( Krstev et al., 2024 ).

Additionally, the conference “The World Ahead of Us – Education in the Era of Artificial Intelligence,” held at the Palace of Serbia, highlighted the latest advancements in AI applications in education, with particular emphasis on the potential of personalized learning, intelligent tutoring systems, and large-scale educational data analytics. These developments underscore the growing need for the development and evaluation of AI algorithms ( Kayal, 2024 ) that are not only technologically efficient but also aligned with pedagogical principles and infrastructural limitations of schools. In line with this, Adžić and colleagues (2024) provide evidence that the acceptance of AI, particularly generative tools, varies across different educational contexts, further emphasizing the necessity for transparent and adaptable evaluation frameworks.

The selection process is further complicated by the fact that decision-makers are often not technical experts, which highlights the need for structured, transparent, and replicable evaluation models ( Sampson et al., 2019 ). In this context, the present study proposes a hybrid multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) framework that integrates the SWARA (Step-wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis) method with Net Worth Analysis (NWA) to evaluate and rank nine contemporary AI algorithms for visual recognition. Drawing on domain expertise in educational technology, the proposed model enables the assessment of algorithms based on criteria that reflect the actual needs of the education system: processing speed, accuracy, robustness to noise, energy efficiency, and suitability for low-end hardware ( Tariq et al., 2024 ).

This approach addresses a gap in the current literature, as most previous studies applying MCDM methods have focused on the selection of e-learning platforms, curricula, or teaching methodologies, while the selection of AI algorithms for educational purposes remains underexplored. The proposed model facilitates a balance between technical performance and educational usability, serving as a practical tool for evidence-based decision-making in the process of educational digital transformation.

Theoretical Framework

In the field of educational engineering, decision-making is increasingly guided by quantitative and systematic approaches, particularly in the selection of technologies, teaching methodologies, educational tools, and infrastructural solutions ( Buenaño-Fernandez et al., 2019 ). Within this context, Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) has emerged as a particularly valuable framework, enabling the evaluation of multiple alternatives based on a variety of often conflicting criteria ( Massam, 1988 ). MCDM methods have proven useful in non-trivial decision-making scenarios that require alignment between technical, pedagogical, organizational, and economic considerations, a fact supported by numerous educational studies ( Malik et al., 2021 ). Recent examples include: Toan et al. (2021) , who employed a hybrid MCDM approach for evaluating e-learning platforms in higher education; Keshavarz-Ghorabaee et al. (2018) , who demonstrated the utility of SWARA and AHP models in selecting digital teaching tools; and Chen and Luo (2023) , who illustrated the effectiveness of fuzzy logic-based MCDM models in assessing teaching quality. Similarly, Mahmoodi et al. (2025) applied MCDM methods to the selection of teaching strategies in STEM education, while Troussas et al. (2025) found TOPSIS and VIKOR techniques beneficial in planning educational infrastructure for primary schools. Marinović et al. (2025) published research optimizing the selection of operating systems within educational contexts.

The Role of MCDM Methods in Educational Contexts

Educational engineering involves the application of engineering principles, systems theory, and design methodologies to the educational process ( Dym, 2004 ). As institutions face increasingly complex decisions, such as the selection of e-learning platforms, learning analytics tools, digital content, and AI algorithms, there is a growing need for transparent and replicable evaluation methods ( Colchester et al., 2017 ).

MCDM methods allow for a structured analysis of alternatives using sets of both quantitative and qualitative criteria ( Sahoo and Goswami, 2023 ). Their value in education is particularly evident in the following cases:

-

• Assessment of digital learning tools and platforms,

-

• Evaluation and selection of adaptive learning software,

-

• Design of data-driven curricula and instructional strategies,

-

• Ranking of teaching methods based on learning outcomes,

-

• Selection of technologies for smart classrooms or AR/VR systems,

-

• Evaluation of AI algorithms for behavior analysis, automated grading, or visual recognition.

Over the past decade, the application of MCDM approaches in education has grown exponentially, both in research and practice, due to their capacity to integrate expert judgment with available data ( Nguyen, 2024 ). This trend is further substantiated by recent studies that emphasize the integration of artificial intelligence in education, such as the work by Milićević et al. (2024) , which outlines current challenges in the implementation of AI in Serbia’s educational system, and Tsankov and Levunlieve (2024) , who examine the structured design of digital content in early childhood education.

Beyond academic insights, concrete shifts in Serbia’s educational landscape further highlight the relevance of MCDM approaches. The introduction of the Unified Information System of Education (JISP), mandatory use of the e-Dnevnik platform, and the nationwide transition to accredited LMS systems illustrate the complexity of selecting technologies that must meet pedagogical, technical, security, and regulatory requirements. By applying MCDM methods, school administrators, ministries, and educational experts can make informed, rational, and well-documented decisions while balancing trade-offs between competing factors such as cost, accessibility, scalability, local support, and personalization capacity ( Popović and Popović, 2021 ; Popović et al., 2022 ).

Moreover, educational development strategies, not only in Serbia and the Western Balkans, but across developed countries, underscore the need for methodological frameworks that support the evaluation and selection of AI solutions in line with strategic goals and the real capacities of educational systems. In this context, the integration of MCDM methods such as SWARA, AHP, TOPSIS, and NWA is not only desirable but essential for the systemic digital transformation of education.

Most Commonly Used MCDM Methods in Education

The most frequently used MCDM methods in educational research and practice include: Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), Step-wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (SWARA), Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Evaluations (PROMETHEE), and PIvotal Point of the Relative Criteria Impact Assessment (PIPRECIA). These methods provide structured and systematic evaluations of multiple alternatives based on a range of criteria-a particularly important feature in educational settings where decisions often involve selecting technologies, curricula, instructional strategies, or student assessment methods. Their application facilitates more transparent, objective, and adaptable decision-making by addressing the inherent complexity of the educational process and incorporating the diverse perspectives of stakeholders ( Vien- net and Pont, 2017 ). In recent years, there has been an increasing number of studies combining MCDM methods with expertise in educational technology to optimize tools and strategies ( Alshamsi et al., 2023 ).

Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

AHP is one of the most widely used methods, designed for hierarchically structuring problems and performing pair wise comparisons of criteria and alternatives. Its popularity in education stems from its ability to break down complex decisions into smaller, logically related components that are easier to analyze. The method supports expert subjective judgments and converts them into quantitative values, enabling the analysis of qualitative aspects within education. As such, AHP has become an important tool for strategic educational decision-making across all levels of governance ( Vaidya and Kumar, 2006 ).

Common educational applications include:

-

• Selection of distance learning platforms,

-

• Prioritization of educational objectives,

-

• Evaluation of educational program quality.

Its advantages lie in its systematic structure and analytical rigor, while its limitations include complexity when handling many criteria and the requirement to check consistency.

Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS)

TOPSIS identifies the optimal solution as the one closest to the ideal and farthest from the worst case scenario. This method is especially useful in education due to its clear and intuitive ranking of alternatives against predefined criteria. Its ability to balance between positive and negative ideal values makes it suitable for decision making situations that require compromise, which is often the case in educational practice. Because of its flexibility and transparency, TOPSIS has become a favored tool among researchers and policy makers in the education sector ( Behzadian et al., 2012 ).

Applications include:

-

• Ranking teaching strategies,

-

• Selection of technologies in higher education,

-

• Evaluation of educational applications.

While TOPSIS offers intuitive interpretation, it relies on proper data normalization and accurate weighting.

Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Evaluations (PROMETHEE)

PROMETHEE uses preference functions and provides flexibility in assessing qualitative criteria. It is particularly suitable for complex educational problems involving multiple alternatives with differing characteristics. Its ability to process both quantitative and qualitative data makes it valuable for analyses involving subjective values, such as pedagogical approaches, student motivation, or the interactivity of learning materials. PROMETHEE also offers visualization through GAIA planes, facilitating decision making in educational institutions ( Brans and Mareschal, 2005 ).

It is commonly applied in:

-

• Selecting teaching methodologies,

-

• Choosing courses within study programs,

-

• Analyzing educational scenarios.

However, it requires expertise in defining preference functions, which can be challenging for non-experts.

Step-wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (SWARA)

SWARA is designed to determine weighting coefficients based on expert opinion. Its strength lies in its ability to transparently convert qualitative expert assessments into quantitative values suitable for MCDM analysis. It is particularly applicable in educational contexts where exact data may be lacking, and expert knowledge is the primary decision making resource. For these reasons, SWARA was selected as the most appropriate method for achieving the research goals of this study ( Keršulienė et al., 2010 ).

Advantages include:

-

• Ease of application,

-

• Suitability for expert-driven contexts,

-

• Support for consensus-based decision-making.

In educational engineering, SWARA is used to:

-

• Prioritize learning quality factors,

-

• Evaluate technology selection criteria,

-

• Determine the importance of competencies in curricula.

Its intuitive structure and lower cognitive load make SWARA especially suitable for educational institutions.

PIvotal Point of the Relative Criteria Impact Assessment (PIPRECIA)

PIPRECIA uses a penalization approach to determine the relative importance of criteria. Unlike traditional weighting methods, it incorporates the influence of each subsequent evaluation through a penalization mechanism, enabling more precise prioritization. It is thus well suited for complex decisions involving numerous criteria and stakeholders. In academic environments, PIPRECIA has proven to be a fast and effective method that delivers consistent results with minimal cognitive burden for experts. Its strength lies in its efficiency when dealing with large sets of criteria and in providing timely results. It is increasingly applied in educational studies, particularly for evaluating policies, strategies, and new curricular designs (Pamučar and Ćirović, 2015).

Integration of MCDM Methods with Educational Technology Systems

In the context of Serbia’s digital transformation of education, there is a pressing need for multi-criteria decision models that combine expert knowledge with quantitative data. The proposed hybrid model integrates AHP, TOPSIS, PROMETHEE, SWARA, and PIPRECIA, enabling comprehensive and flexible analysis of educational decisions. AHP structures the problem and determines weights; TOPSIS identifies optimal solutions based on proximity to ideal values; PROMETHEE addresses subjective aspects through preference functions; SWARA facilitates the integration of expert opinions; and PIPRECIA allows efficient evaluation through penalization. This model can be applied to selecting digital platforms, evaluating AI solutions, budgeting for EdTech, and supporting school level digital decision-making. It is compatible with tools such as MATLAB, Excel, Python libraries, and interactive web platforms, offering visualization, interactive analysis, and real-time adaptability. The SWARA–NWA approach further balances subjective expert insight with objective algorithm performance, enhancing methodological transparency and applicability in educational practice.

Relevance for Selecting AI Algorithms in Education

Most existing research on MCDM in education focuses on the selection of platforms, learning methods, or instructional content. However, the growing use of artificial intelligence and computer vision in educational applications, such as automated grading, visual analytics, and behavior detection, necessitates the use of MCDM techniques to support the selection of appropriate AI algorithms.

This study addresses that gap by:

-

• Defining criteria relevant to the educational context (e.g., computational efficiency, pattern accuracy, robustness to noise),

-

• Applying a well-established hybrid MCDM approach (SWARA–NWA),

-

• And evaluating a set of widely-used computer vision algorithms that are increasingly adopted in educational systems.

Methodology

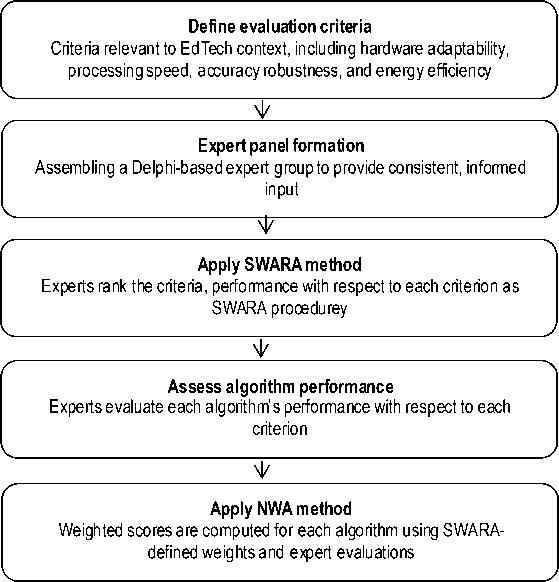

This study (see Figure 1) employs a hybrid Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) approach, combining the Step-wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (SWARA) method for determining the relative importance of evaluation criteria and the Net Worth Analysis (NWA) method for calculating overall scores and ranking AI algorithms in an educational technology context.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the SWARA-NWA Hybrid Evaluation Framework Source: Author’s research

Steps of the SWARA Method

The SWARA method ( Keršulienė et al., 2010 ) enables experts in the fields of education and artificial intelligence to express their judgments regarding the relative importance of predefined evaluation criteria.

-

1. Criteria Prioritization

-

2. Relative Importance (si)

Experts rank the criteria in descending order of importance-from the most to the least significant.

(This is a qualitative step that precedes the quantitative analysis.)

Starting from the second criterion, experts estimate how much less important each criterion is in comparison to the previous one:

Si = relative importance of criterion j with respect to criterion j–1

-

S1= 0 (since there is no preceding criterion for the first one)

-

3. Correction Coefficients

-

4. Recalculated Weights (qj)

Correction coefficients are calculated using the formula:

ki = si + 1 = sj + 1, where ki = 1 and j = 2, 3, … ,

-

a) Raw weights (wj):

wj = 1

1 , wj =k2xk3 x - x kj for j = 2,3,... ,n

-

b) Normalized weights (qj):

Criteria Definition and Expert Panel

For the purpose of this research, five criteria were defined as particularly relevant for educational settings:

-

• Computational efficiency (e.g., hardware requirements and startup speed),

-

• Processing speed (real-time execution performance),

-

• Pattern recognition accuracy (correct identification of handwriting, symbols, or educational elements),

-

• Robustness to noise (e.g., variations in lighting and background),

-

• Energy efficiency (power consumption in mobile or IoT environments).

To obtain reliable expert consensus, the Delphi method was employed, a widely recognized iterative technique for structured elicitation and aggregation of expert opinion under conditions of uncertainty and subjectivity ( Hsu and Sandford, 2007 ).

Application of the NWA Method

Following the determination of criteria weights using the SWARA method, the Net Worth Analysis (NWA) approach ( Zangemeister, 1976 ) was applied to aggregate performance values and compute the final score for each algorithm.

The overall score S for each algorithm A is calculated using the following formula:

si = 7 Ъ ' vi ^/=1

Where:

-

• S represents the total score of algorithm i ,

-

• qj is the normalized weight of criterion j (from SWARA),

-

• vj is the performance of algorithm i with respect to criterion j ,

-

• n is the total number of criteria.

The performance values vj were assigned by domain experts based on a review of prior studies, technical documentation, and practical use in educational tools.

Method Integration

The structured hybrid model ensures transparency and reproducibility in the evaluation process by combining subjective expert judgments with quantitative aggregation ( Zellner et al., 2021 ). The integration of SWARA and NWA allows expert opinions to be transformed into numerical scores, facilitating objective comparison between alternatives while preserving flexibility in assessing qualitative dimensions.

This dual-layered approach provides a balanced interplay between analytical formalism and domain-specific expertise, which is particularly vital in educational contexts where evaluation criteria are often multidimensional and interdependent. The resulting output is a ranked list of algorithms according to their suitability for deployment within educational technology systems, enabling decision-makers to identify the most effective options aligned with the specific constraints and pedagogical needs of their institutions.

Evaluation Criteria

The effective integration of artificial intelligence into educational systems requires the careful selection of algorithms that are not only technically advanced but also aligned with pedagogical contexts and infrastructural constraints ( Kaddouri et al., 2025 ). This study defines five key evaluation criteria that reflect the practical needs of educational institutions, particularly in the context of smart classrooms, mobile learning, and digital platforms with limited hardware capabilities. A similar approach is evident in studies on the integration of sensors and AI in smart classrooms, which emphasize the need to balance pedagogical, infrastructural, and technical dimensions (Mircea et al., 2023).

Computational Efficiency

Many primary and secondary schools, as well as educational institutions in rural or underdeveloped regions, lack access to advanced hardware infrastructure. Thus, one of the fundamental evaluation criteria is the algorithm’s ability to operate on low-resource devices, such as older laptops, tablets, or cost-efficient IoT platforms.

Evaluation dimensions include:

-

• Memory efficiency (RAM, GPU usage),

-

• Minimal system requirements for deployment,

-

• Compatibility with mobile and embedded systems (e.g., Raspberry Pi, Android devices).

Algorithms that rely on complex deep neural networks with high inference costs may be unsuitable in educational environments where access to high-performance GPUs is limited.

Processing Speed

Many EdTech applications, especially those used for interactive learning, student monitoring, or automated assessment, require algorithms capable of real-time data processing. Latency in system response can negatively affect user experience, student engagement, and instructional effectiveness.

Assessment is based on:

-

• Average inference time per sample,

-

• Real-time processing capability of video streams,

-

• System responsiveness to user input in interactive applications.

Particular emphasis is placed on algorithms that maintain performance when handling live video or image sequences, which is essential for smart classroom scenarios and augmented reality (AR) applications.

Accuracy

AI algorithms in education must reliably recognize patterns specific to educational activities, including handwritten text, mathematical expressions, student gestures, diagrams, and physical objects used in STEM instruction.

This criterion refers to:

-

• Ability to accurately classify and segment relevant educational elements,

-

• Reduction of false positives and false negatives,

-

• Reliability in evaluating student work.

Accuracy is measured through both technical performance metrics and practical deployments in real-world educational scenarios. Explainability and transparency remain crucial, especially when AI systems influence pedagogical or administrative decisions. Though not limited to education, Spalević et al. (2024) highlight the importance of explainable AI in sensitive systems, a principle that equally applies to the classroom environment.

Robustness to Environmental Noise

Educational environments, particularly mobile learning contexts, often lack controlled lighting conditions. A tablet camera used in a hallway, playground, or brightly lit classroom may capture low-quality images. Therefore, it is essential that algorithms remain stable and accurate under variable conditions.

This criterion includes:

-

• Resistance to changes in lighting (e.g., overexposure, shadows),

-

• Ability to extract relevant features from images with complex backgrounds,

-

• Robustness when handling noise and degraded input quality.

Robust algorithms offer greater flexibility and ensure consistent reliability in everyday teaching scenarios.

Energy Efficiency and Sustainability

Modern education increasingly relies on mobile and IoT technologies. In smart classrooms, devices such as interactive boards, cameras, sensors, and student-owned equipment often depend on battery power or limited energy sources.

The following aspects are particularly valued:

-

• Energy consumption during algorithm execution (e.g., on smartphones, tablets, or Raspberry Pi devices),

-

• Battery life under continuous operation,

-

• Suitability for “green computing” initiatives in education.

Energy efficiency is regarded as a critical sustainability metric, both from an economic perspective and in terms of environmental responsibility, including the reduction of CO2 emissions.

Case Study

To ensure that the evaluation of AI algorithms for educational purposes yields relevant and applicable results, a case study was conducted involving a panel of experts specializing in educational technology and the application of artificial intelligence in education. Expert judgment constitutes a fundamental component of the SWARA methodology, as both the weights of the evaluation criteria and the performance assessments of algorithms are grounded in professional expertise and consensus.

Selection and Profile of Experts

For the purposes of this study, a panel of seven experts was assembled, each with substantial experience across different domains of educational technology.

The selection criteria for expert inclusion were as follows:

-

• A minimum of five years of professional experience in the development or implementation of EdTech solutions, or in teaching within the fields of information technology and computer science;

-

• Active involvement in research or development of AI applications in education;

-

• Proficiency in computer vision, adaptive learning systems, or smart classroom technologies.

The composition of the expert panel was as follows:

-

• 2 university professors with expertise in artificial intelligence and practical experience in higher education instruction,

-

• 2 EdTech software engineers involved in the development of adaptive learning and assessment platforms,

-

• 1 researcher in the field of human-computer interaction and student behavior analysis,

-

• 1 computer science teacher with practical experience in applying AI tools in classroom settings,

-

• 1 education policy specialist focused on digital transformation and inclusive education initiatives.

This interdisciplinary composition enabled the evaluation process to integrate diverse perspectives, ranging from instructional and practical viewpoints to research-oriented and strategic dimensions.

Evaluation Procedure and Consensus Building

The evaluation was conducted in two phases using the Delphi method, allowing for iterative consensus development while preserving the anonymity of individual expert responses.

Phase one involved individual assessment of the following:

-

• The relative importance of each of the five predefined evaluation criteria (via the SWARA method),

-

• The performance of each algorithm according to the specified criteria (via the NWA method).

Experts used a five-point scale (where 5 indicated the highest possible value) and were encouraged to provide additional qualitative comments and recommendations.

In phase two, aggregated results from the first round were presented to the experts, who were then given the opportunity to revise their initial evaluations in light of observed trends. This procedure resulted in a high level of consensus without the influence of dominant individuals. All responses remained anony- mous, and communication was facilitated through an online platform specifically designed for structured survey-based expert elicitation.

Data Validation and Reliability

To ensure data reliability, several control measures were implemented:

-

• Consistency checks among expert responses (standard deviation < 0.6 in the majority of cases),

-

• Cross-referencing with published literature and technical documentation for each algorithm,

-

• Technical briefings that included concise presentations and practical examples of each algorithm’s potential use in educational scenarios.

Based on expert assessments and the validated dataset, the SWARA method was applied to calculate the criterion weights, followed by the application of the NWA method to derive the final score and ranking for each algorithm.

Results and Discussion

This section presents and interprets the findings obtained through the application of the hybrid SWARA–NWA model for evaluating nine artificial intelligence algorithms within the context of educational technology. The analysis was conducted in three stages: determining the weights of evaluation criteria, assessing algorithm performance according to each criterion, and calculating the total scores to establish a final ranking.

Criterion Weights

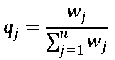

Table 1 displays the results derived from the SWARA method, used to determine the relative importance of five predefined evaluation criteria in the context of EdTech applications. Based on the input of seven experts in educational technology and AI implementation in education, “computational efficiency” was identified as the most significant criterion, receiving a subjective weight of 0.20 and a final normalized weight (qj) of 0.250. This high value reflects the practical need for algorithms that can operate effectively on older computers, tablets, and low-performance devices within educational institutions.

Table 1. SWARA-Based Weight Coefficients for Evaluation Criteria (Source: Author’s research)

Criterion (Sj) (Kj = Sj + 1) (Wj) (qj)

|

Computational efficiency |

0.2 |

1.20 |

1 |

0.250 |

|

Processing speed |

0.15 |

1.15 |

0.870 |

0.217 |

|

Pattern accuracy |

0.12 |

1.12 |

0.776 |

0.194 |

|

Noise robustness |

0.1 |

1.10 |

0.706 |

0.176 |

|

Energy efficiency |

0.08 |

1.08 |

0.654 |

0.163 |

The second most important criterion, according to the experts, was “processing speed” (qj = 0.217), as rapid system response is critical for user experience and instructional efficacy in interactive classrooms and adaptive platforms. “Pattern accuracy” was ranked third (qj = 0.194), as it reflects the algorithm’s ability to reliably recognize handwriting, symbols, diagrams, and other educational elements. The remaining two criteria, “robustness to noise” and “energy efficiency”, received slightly lower final weights (0.176 and 0.163, respectively), though still recognized as relevant, particularly in mobile learning environments and scenarios with unfavorable lighting conditions.

Figure 2. SWARA Criterion Evaluation Overview (Source: Author’s research)

These results clearly indicate that experts favored algorithms enabling broad and inclusive application across diverse educational settings, consistent with the strategic aims of digital transformation in education.

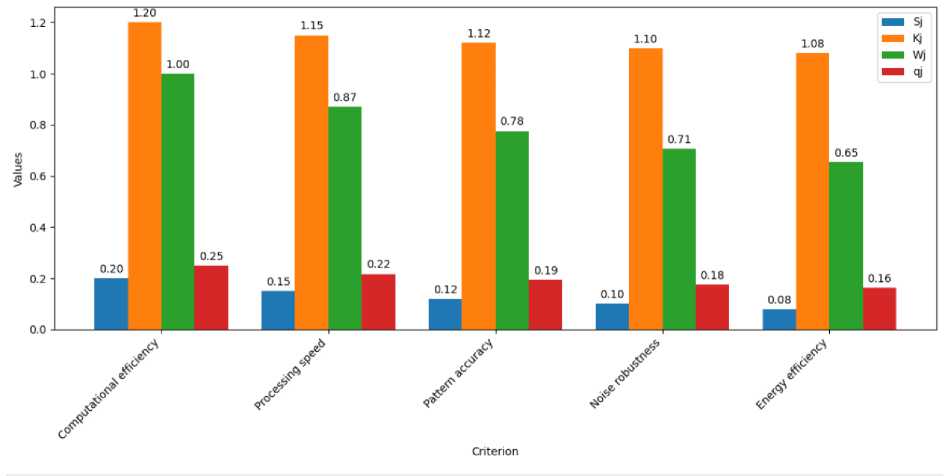

Algorithm Performance Scores

Table 2 presents expert-assigned performance scores for the nine evaluated algorithms across all five criteria. These scores served as input values for the NWA phase, allowing for a detailed comparison prior to score aggregation.

|

Table 2. Expert Performance Scores of AI Algorithms According to Evaluation Criteria (Source: Author’s research) |

|||||

|

Algorithm |

Computational Efficiency |

Processing Speed |

Pattern Accuracy |

Noise Robustness |

Energy Efficiency |

|

Fast R-CNN |

0.193 |

0.245 |

0.213 |

0.245 |

0.245 |

|

U-Net |

0.193 |

0.213 |

0.245 |

0.213 |

0.213 |

|

DeepLab |

0.178 |

0.213 |

0.245 |

0.213 |

0.213 |

|

MobileNet |

0.245 |

0.213 |

0.193 |

0.193 |

0.213 |

|

ResNet |

0.213 |

0.193 |

0.160 |

0.245 |

0.245 |

|

Binary Segmentation |

0.245 |

0.245 |

0.213 |

0.178 |

0.160 |

|

YOLO |

0.213 |

0.245 |

0.193 |

0.193 |

0.193 |

|

FCN |

0.193 |

0.193 |

0.178 |

0.213 |

0.178 |

|

EfficientDet |

0.245 |

0.160 |

0.160 |

0.160 |

0.160 |

The analysis shows that Fast R-CNN received the highest scores in nearly all categories, particularly in processing speed, robustness, and energy efficiency (0.245 each). Although not the lightest in terms of hardware requirements, its score of 0.193 for computational efficiency suggests acceptable resource demands.

Figure 3. Algorithm Evaluation Across Criteria (Source: Author’s research)

U-Net and DeepLab excelled in pattern recognition accuracy (0.245), making them particularly suitable for educational tasks requiring precise interpretation of visual content, such as diagrams and handwritten assignments.

MobileNet performed strongly in computational efficiency (0.245) and energy balance (0.213), rendering it well-suited for BYOD (Bring Your Own Device) strategies and mobile classrooms.

Interestingly, industrially successful models such as ResNet and EfficientDet performed relatively poorly on education-specific criteria. EfficientDet, in particular, received the lowest scores across almost all dimensions, suggesting that its deployment in education would require significant optimization. Binary Segmentation, although very fast (0.245), underperformed in terms of robustness (0.178) and energy efficiency (0.160), limiting its utility in energy-constrained or dynamic environments.

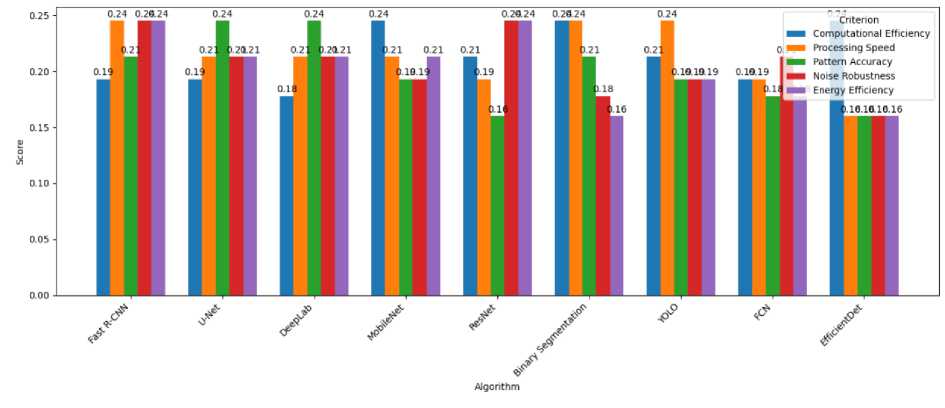

Final Results

Table 3 presents the final NWA scores obtained by applying the weights from Table 1 to the expert scores from Table 2. The algorithms are ranked from 1 to 9 according to their overall suitability.

Table 3. Final NWA Scores and Ranking of AI Algorithms (Source: Author’s research)

|

Algorithm |

Total Score |

Rank |

|

Fast R-CNN |

1.141 |

1 |

|

U-Net |

1.077 |

2 |

|

DeepLab |

1.062 |

3 |

|

MobileNet |

1.057 |

4 |

|

ResNet |

1.056 |

5 |

|

Binary Segmentation |

1.041 |

6 |

|

YOLO |

1.037 |

7 |

|

FCN |

0.955 |

8 |

|

EfficientDet |

0.885 |

9 |

Fast R-CNN achieved the highest total score (1.141), affirming its overall adaptability to the requirements of educational technology. It offers a favorable balance between speed, robustness, and energy efficiency, with reasonable scalability.

U-Net (1.077) ranked second due to its high segmentation accuracy and solid performance across other criteria. It is especially promising for tasks such as automatic evaluation of handwritten work and visual analysis of student responses.

DeepLab (1.062) came in third, characterized by high precision and robustness, making it suitable for AR/VR applications in education.

MobileNet (1.057) and ResNet (1.056) had nearly identical total scores. The former is recommended for mobile applications and low-power environments, while the latter performs reliably in unstructured settings such as outdoor or field-based learning.

The remaining algorithms, FCN, Binary Segmentation, YOLO, and EfficientDet, showed limitations across multiple criteria. While not inherently unsuitable, their deployment would require targeted adaptation, hybrid integration, or use in narrowly defined tasks with specific performance requirements.

Unlike previous studies that employed MCDM methods to select e-learning platforms, curricula, or teaching strategies, this research focuses on evaluating specific computer vision algorithms within educational contexts. For instance, Toan et al. (2021) applied a hybrid AHP–COPRAS model for selecting e-learning systems, and Keshavarz-Ghorabaee et al. (2018) used SWARA and AHP for evaluating digital teaching tools. Marinović et al. (2025) employed the PIPRECIA method to optimize operating system selection in schools. Compared to these approaches, the proposed SWARA–NWA framework enables direct evaluation of AI algorithms based on education-specific criteria such as computational efficiency, robustness to environmental noise, and operability on low-end hardware. This methodological distinction makes the model particularly suitable for decision support in real-world EdTech scenarios, especially in resource-constrained educational settings.

Research Limitations

While the hybrid SWARA–NWA model offers a structured and transparent framework for evaluating AI algorithms in educational environments, several limitations must be acknowledged that may influence the scope and applicability of the findings:

-

1. Subjectivity of expert evaluations – The methodology relies on expert judgment to assign weights and assess algorithm performance, introducing a level of subjectivity.

-

2. Limited number of experts – The panel consisted of seven experts, which is appropriate for the Delphi method, yet a larger sample would enhance statistical validation and understanding of assessment variability.

-

3. Theoretical rather than experimental validation – Algorithm evaluation was based on technical documentation and expert analysis, without direct benchmarking on real educational datasets.

-

4. Restricted set of evaluation criteria – Although the five selected criteria were carefully chosen for EdTech relevance, real-world decision-making may require consideration of additional factors such as implementation costs, technical support availability, user digital literacy, and alignment with local educational policies.

-

5. Focus on computer vision algorithms only – While the selected algorithms are among the most commonly used in AI applications, the study does not address other domains such as natural language processing (NLP), recommendation systems, or intelligent tutoring systems, which are also highly relevant in modern education.

Conclusion

This study presents a hybrid multi-criteria decision-making model based on the SWARA and Net Worth Analysis (NWA) methods for the evaluation of artificial intelligence algorithms in the context of educational technology. The primary objective was to provide a transparent and systematic framework that supports educational institutions, IT teams, and policy makers in selecting the most appropriate AI algorithms tailored to the specific needs of EdTech applications.

Figure 4. Graphical Representation of the Final Results of the Hybrid Model (Source: Author’s research)

The evaluation focused on computer vision algorithms and incorporated five key criteria relevant to educational scenarios: computational efficiency, processing speed, pattern recognition accuracy, robustness to lighting and background disturbances, and energy efficiency. The SWARA method was applied to determine the relative importance of each criterion based on expert assessments, while the NWA method was used to aggregate the performance scores of each algorithm and generate a final ranking, as illustrated in Figure 2.

The findings indicate that Fast R-CNN emerged as the most suitable algorithm for widespread deployment in educational systems, owing to its balanced performance across all criteria. U-Net and DeepLab stood out for their superior accuracy in visual segmentation, making them particularly well-suited for specialized educational tasks that involve complex visual pattern analysis. MobileNet, due to its lightweight architecture and energy efficiency, proved to be an ideal solution for mobile and resource-constrained environments, particularly within the context of inclusive education in underserved regions.

Recommendations for Future Research

Based on the findings and identified limitations of the present study, we propose the following directions for future research:

-

• Empirical validation of the model – Future studies should incorporate experimental testing of the algorithms using real-world educational datasets to complement and verify the theoretical assessments.

-

• Expansion of the algorithm pool – Include algorithms from other areas of AI, such as natural language processing (NLP), recommender systems, and classification models.

-

• Incorporation of additional evaluation criteria – Such as cost-efficiency, availability of open-source implementations, compliance with educational standards, and required teacher training.

-

• Application of alternative MCDM methods – Including AHP, PIPRECIA, or fuzzy MCDM approaches, to compare outcomes and test the robustness of the proposed model.

-

• Involvement of end users (teachers and students) – Through interviews, surveys, and pilot testing to enrich the results with insights drawn from real-life educational experiences.

The proposed model represents a significant methodological advancement toward the rationalization and formalization of decision-making processes related to the adoption of AI-based technologies in education. In the current era of accelerated digital transformation, where educational institutions are striving to balance innovation with systemic constraints, it becomes evident that decision-making based on intuition or fragmented information is no longer sufficient. What is needed is a robust, transparent, and multi-criteria framework that facilitates the inclusion of diverse stakeholder groups, from teachers and learners to IT specialists and educational authorities.

Acknowledgements

The research presented in this paper was carried out within the framework of the project: Multicriteria analysis modeling for decision optimization in computer sciences, at Alfa BK University, Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Sciences, No. 1760.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the reported results in this study are contained within the article itself.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Nikola Gligorijević: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Nikola Gligorijević is the first author and led the research design and implementation of the hybrid SWARA-NWA model.; Sonja Đukić Popović: Validation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Data curation.;