Analysis of Trainee Satisfaction with Mentorship in Early and Preschool Education Using Artificial Neural Networks

Автор: Tihana Kokanović, Antonija Vukašinović, Siniša Opić

Журнал: International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education @ijcrsee

Рубрика: Original research

Статья в выпуске: 3 vol.13, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Effective mentoring is grounded in reciprocal collaboration between mentors and trainees, where mutual respect and open, reflective dialogue are essential from the very beginning of the internship. The aim of this study was to examine which factors predict trainees’ satisfaction with their mentors by applying a predictive model. The sample consisted of 104 trainee preschool teachers from Croatia. To test the model, perceptron artificial neural networks were used (with one hidden layer and four neurons), employing the hyperbolic tangent activation function. The results indicated a low discrepancy between the training and test datasets, high classification accuracy, and balanced TPR and TNR values, with an AUC above 0.95, confirming excellent predictive model accuracy. The analysis further revealed the relative predictive strength of individual factors related to satisfaction with the quality of mentor cooperation. The mentor–trainee relationship emerged as the strongest predictor, while net salary proved to be a more influential predictor of satisfaction with mentor cooperation than support from principals or professional associates.

Mentor–trainee relationship, machine learning in education, factors of satisfaction

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170211404

IDR: 170211404 | УДК: 373.2.011.3-051:331.108.38; 37.064.2 | DOI: 10.23947/2334-8496-2025-13-3-625-635

Текст научной статьи Analysis of Trainee Satisfaction with Mentorship in Early and Preschool Education Using Artificial Neural Networks

Mentorship is a practice in which a more experienced educator, referred to as a mentor, provides support, guidance, advice, and encouragement to a novice or less experienced educator, referred to as a mentee—in this case, a preschool teacher trainee (Bressman et al., 2018). The primary aim of this practice is to improve the overall quality of teaching and learning in preschool institutions. A preschool teacher trainee, without prior professional experience, acquires relevant knowledge and develops professional competencies during a one-year traineeship in preschool institutions, supported by a mentor and the insti-tution.The objectives of preschool teacher traineeship programs include enhancing trainees’ competence, quality of practice, motivation, job satisfaction, career opportunities, and fostering personal achievement (Hadley et al., 2024; Ingersoll, 2012). Support provided by mentors, professional staff, and the principal within the preschool institution is positively associated with a smoother and more effective transition from traineeship to professional teaching, reduced levels of professional burnout, and sustained motivation for educational work (Carmel and Paul, 2015). The content of the traineeship program is designed to equip preschool teacher trainees with the competencies and sense of responsibility required to fulfill their social role within the educational system (Vassileva, 2021). The core tasks of preschool teacher trainees encompass the application of theoretical knowledge in professional practice, the use of diverse pedagogical strategies to foster children’s development, the planning and organization of educational activities, and the enhancement of communication skills. These tasks often represent a considerable challenge for novice practitioners (Carmel et al., 2023).

Within this process, collaboration with the mentor, systematic exchange of information, and ongoing evaluation constitute essential dimensions of professional development. In Croatia, the traineeship

© 2025 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license .

of preschool teachers is implemented in accordance with a program proposed by the traineeship committee and formally approved by the designated professional body of the preschool institution. This committee—composed of the principal, the mentor, and a professional associate—is responsible for program design, provision of professional support to the trainee, and systematic monitoring of their progress. The mentor, who maintains official records of the traineeship, is typically an educator who has successfully passed the state professional examination.The Regulation on the Procedure, Methods, and Conditions for Career Advancement and the Attainment of Professional Titles of Preschool Teachers, Professional As sociates, and Principals in Preschools (NN 133/1997, NN 83/2024) establishes that educators possessing the required professional qualifications and meeting the prescribed evaluation standards are eligible for career advancement and the attainment of the professional titles of Mentor, Advisor, and Senior Advisor. The evaluation of mentors’ expertise and quality of practice is based both on demonstrated effectiveness in educational work and on their continuous engagement in professional learning and development.In the Republic of Croatia, the induction year for preschool teacher trainees lasts for one year, starting from the date of employment. Preschool institutions are required to adopt a formal probationary program within 15 days of employing a trainee, appoint a traineeship committee, and report the induction to the competent authorities. The Regulation on the Procedures and Conditions for Taking the Professional Examination for Preschool Teachers and Professional Associates in Preschools (NN 133/1997, NN 84/2024) specifies the mandatory content of the program. In addition, preschool teacher trainees are obliged to participate in structured professional development and to engage in a minimum of 30 hours of mentoring with their assigned mentor.The traineeship committee is required to observe the trainee’s professional practice at least twice during the probationary period. Upon completion, the trainee must sit a teacher certification examination, which consists of three components: a written test, an oral examination, and a practical assessment.

Factors Influencing Preschool Teacher Trainees’ Satisfaction with the Induction Program

For a successful and effective induction period, as well as for establishing a high-quality mentoring relationship, it is essential to maintain a collaborative relationship with the mentor ( Ewing, 2021 ; Shanks et al., 2020 ), mutual understanding ( Goodwin et al., 2021 ), acceptance of diverse professional roles, and reciprocal respect ( Ambrosetti, 2014 ; Ingleby, 2014 ; Kupila et al., 2017 ). David and Kim (2023) emphasize the importance of transforming mentorship into a democratic process in which both participants respect one another with the aim of achieving positive outcomes. A key characteristic of the mentor–trainee relationship is the establishment of an open, reflective dialogue from the very beginning of the induction period. Izadinia (2016) stresses that a high-quality mentoring process relies on systematic, constructive, and timely feedback, as well as active listening. According to Nesbit et al. (2025) , mentorship is based on the premise that trainees improve their practice through everyday interactions with other educators and their mentor, and that professional development linked to the environment in which educators carry out their educational practice leads to sustainable and meaningful change. In this context, the collaborative process between the mentor and the trainee involves three critical steps: Goal-setting , including the identification of the necessary steps to achieve those goals; Targeted observations of educational practice aligned with the identified goals; and Provision of feedback by the mentor and modeling to improve pedagogical practice, complemented by reflective practice. Dreer-Goethe (2023) highlights that the well-being of preschool teacher trainees is closely associated with the quality of mentorship. This connection encompasses the mentor’s perception of the mentoring process, their decision to engage in the process, their contribution to the functionality of the mentor–trainee relationship, as well as their choice and application of mentoring styles that support the well-being of both mentor and mentee. Furthermore, the conceptual hypothesis suggests that the quality of mentoring is linked to the well-being of the trainee, which in turn is connected to their professional development. Many of these relationships appear to be reciprocal, implying that mentors’ well-being also contributes to the quality of mentorship and to the well-being of the trainees themselves. Findings from Dreer-Goethe (2023) research with mentors and trainees indicate that the well-being of both parties is strongly shaped by the broader context in which the mentoring process takes place.

In a study conducted by Hudson (2013), both mentors and trainees were examined within a mentorship program that focused on relationships, school culture, and infrastructure, as well as on five key factors of mentorship: personal attributes, systemic requirements, pedagogical knowledge, modeling and feedback, and problem-solving and leadership. The findings indicated that material conditions represent- ed one of the motivating factors for trainees to actively engage in the induction program. Mentors emphasized that their everyday professional experiences were new learning opportunities for trainees, while the trainees expressed overall satisfaction with the mentoring process. The mentors’ focus was primarily on lesson planning, instructional preparation, and the development of classroom management strategies, alongside reflections on their personal teaching philosophies and theories of learning. Similarly, Andrews et al. (2024) argue that the primary goal of formal mentorship is to provide sustained support to trainees in their professional development. Their study examined the experiences of 145 preschool teacher trainees during the first five years of their professional careers, supported by 51 experienced mentors. The project began with a mentor training course, and data were collected through pre- and post-mentoring surveys. The results demonstrated that preschool teacher trainees gained a clearer understanding of their professional role, developed stronger collegial relationships with other educators, and that effective mentorship can significantly contribute to addressing the challenges encountered by novice teachers. The study conducted by Ben-Amram and Davidovitch (2024) involved 46 mentors. Their findings indicate that mentors are primarily motivated by a personal mission and an intrinsic desire to provide support to trainees. Achievement of personal values, vision, and the challenges inherent in mentoring were highlighted as significant motivational factors. Mentors made substantial contributions to trainees’ planning of educational activities and the development of their professional identity. Similarly, the research by De Ossorno Garcia and Doyle (2021) suggests that, from the perspective of trainees, the psychosocial function represents a critical component of the mentor–trainee relationship. Data analyses indicated that preschool teacher trainees emphasize trust, decision-making, personality, and self-efficacy as key motivational factors. In contrast, mentors tend to focus on career development and the fulfillment of programmatic aspects, including monitoring interaction frequency and transferring professional knowledge to trainees.

Beyond the mentor, the principal plays a pivotal role in developing a shared vision for the institution and empowering staff to achieve set objectives. Active participation of principals in educational practice fosters cohesion among teachers and ensures collegiality, which is essential for the successful implementation of pedagogical activities ( Niklasson, 2019 ; Tynjälä and Heikkinen, 2011 ). Principals who cultivate positive relationships with staff and create a supportive organizational culture contribute to increased teacher autonomy in the teaching process. Support provided by principals to trainees during the induction year includes ensuring high-quality mentorship. Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond (2017) emphasize the importance of securing financial resources to sustain mentorship programs. Structured induction programs that include mentor assignment, regular meetings, observation and feedback sessions, discussion of educational practices, and the development of professional growth plans have been shown to be effective in facilitating mentorship. Findings from Li and Khairani (2025) underline several implications for preschool teacher induction programs. The establishment of strong social support systems within the induction process fosters the development of positive pedagogical beliefs among trainees and reinforces their theoretical pedagogical identity. Mentorship programs, collaborative engagement, and inclusion of all participants in the educational process are highlighted as critical components in the professional development of preschool teacher trainees.

Given that the transition from initial education to professional teaching practice is recognized as a critical period in defining each educator as a professional, this study aimed to explore, through assessments by novice educators, their relationship with mentors, satisfaction with the implementation of the induction program, and perceptions of support provided by principals and professional associates.

Materials and Methods

Research Aim

The aim of the study was to identify predictors of preschool teacher trainees’ satisfaction with mentors using Machine Learning – Perceptron Artificial Neural Networks .

Sample

The participants consisted of novice preschool teachers (n = 104) from Croatia. To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the research topic, the study included educators with up to seven years of professional experience, as they were considered capable of reliably evaluating their induction experi-ences.The age distribution of participants was as follows: 41 participants were under 25 years of age, 49 participants were aged 26–35, 12 participants were aged 36–44, and 2 participants were aged 45–55. Regarding professional experience, participants were included if they had completed their traineeship within the past seven years. The distribution of participants according to years of service was as follows: 41 participants had up to 2 years of experience, 32 participants had 3–4 years of experience, and 31 participants had 5–7 years of experience.

Data Collection Method

Data were collected using the Mentor Relationship Assessment Scale ( Vizek Vidović, 2011 ), which consists of 18 items. Two additional subscales were constructed: Principal Support and Professional Associates’ Support . The Principal Support subscale included the following items:v19: During my induction year, I received support and assistance from the principal.v22: The principal treated me as an equal partner during my induction year.v23: The principal showed interest in my professional development during the induction year.v25: The principal monitored and supported all activities in the preschool during my induction year. v27: The principal was sensitive to my needs and those of other staff members during my induction year. v29: The principal provided support and assistance to my mentor during my induction year. The Professional Associates’ Support subscale included the following items: v20: During my induction year, I received support and assistance from professional associates. v21: Professional associates treated me as an equal partner during my induction year. v24: Professional associates showed interest in my professional development during the induction year. v26: Professional associates monitored and supported all activities in the preschool during my induction year. v28: Professional associates were sensitive to my needs and those of other staff members during my induction year. v30: Professional associates provided support and assistance to my mentor during my induction year. Participants indicated their level of agreement on a 3-point Likert scale , with the following response options: 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Partially agree, and 3 = Strongly agree. At the end of the questionnaire, participants were also asked to evaluate their overall satisfaction with the quality of collaboration with their mentor, using a 3-point scale (1 = dissatisfied, 2 = satisfied, 3 = very satisfied). Data were collected via a Google Docs form between June and September 2024. The questionnaire link was distributed through principals, professional associates, and Preschool Teachers’ Associations in Croatia, who then forwarded it to the educators. Participation was anonymous, and respondents were informed that they could withdraw from the survey at any time.

Results

Three composite predictor variables were constructed (Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Composite Variables

|

Min |

Max |

Me |

an |

Mode |

Med |

Std. Dev. |

Skew |

ness |

Kurt |

osis |

|

|

Stat |

Stat |

Stat |

Std. Error |

Stat |

Stat |

Std. Error |

Stat |

Std. Error |

|||

|

Mentor Relationship (KOMP1) |

1,0 |

3,0 |

2,45 |

,064 |

3 |

2,83 |

,660 |

-,954 |

,237 |

-,533 |

,469 |

|

Professional Associates’ Support (KOMP2) |

1,0 |

3,0 |

2,20 |

,064 |

3 |

2,33 |

,655 |

-,461 |

,237 |

-1,01 |

,469 |

|

Principal Support (KOMP3) |

1,0 |

3,0 |

2,24 |

,068 |

3 |

2,50 |

,699 |

-,493 |

,237 |

-1,22 |

,469 |

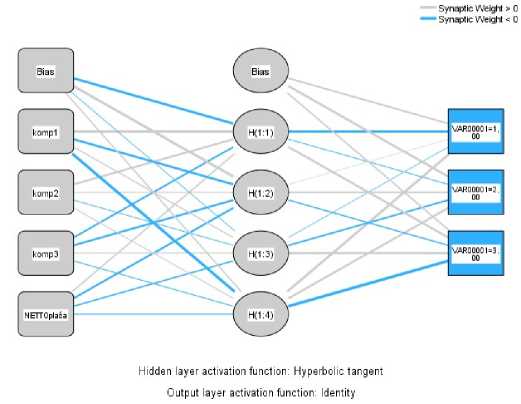

All composite variables were measured on a 3-point Likert scale, with the following response options: 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Partially agree, and 3 = Strongly agree. As indicated, the composite variables exhibit high mean values, low standard errors, left-skewed (negatively skewed), and slightly platykurtic distributions. The dependent variable, Overall, how satisfied are you with the quality of collaboration with your mentor?, was also measured on a 3-point scale (1 = dissatisfied, 2 = satisfied, 3 = very satisfied). Descriptive statistics for the dependent variable are as follows: range = 2, mean = 2.55, standard error of the mean = 0.069, SD = 0.708, skewness = -1.295, kurtosis = 0.233. These distributions suggest that participants generally reported high satisfaction with mentor collaboration, with responses tending toward the upper end of the scale. To assess the significance of the model, Machine Learning using a Perceptron Artificial Neural Network (ANN) was employed. The model consisted of three layers: one input layer, one hidden layer with 4 neurons (nodes), and one output layer with +2 bias units. The Perceptron ANN is a complex, non-parametric mathematical model designed to mimic the functioning of neurons in the brain. It identifies complex relationships among sets of variables and functions as a predictive model based on a loss function. A hyperbolic tangent (tanh) activation function was used (Figure 1). The primary goal was to test the predictive model, specifically the role of predictors on overall satisfaction with mentor collaboration. Initially, independent variables such as gender, age, years of service, preschool size, and professional development were included; however, the model performance was suboptimal. Consequently, these variables were excluded, and the final model incorporated salary (≤1000€: 35 participants, 33.7%; 1001–1200€: 40 participants, 38.5%; 1201–1500€: 26 participants, 25%; 1501–1800€: 3 participants, 2.9%) along with three composite variables: Mentor Relationship (KOMP1), Professional Associates’ Support (KOMP2), and Principal Support (KOMP3).

Figure 1. Three-layer model with 4 neurons (nodes) in the hidden layer

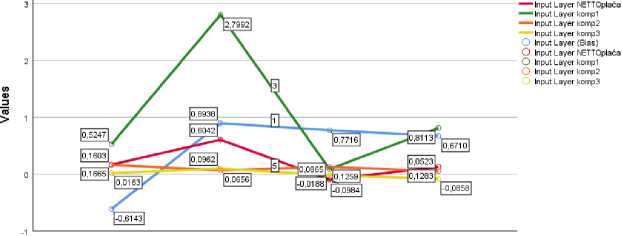

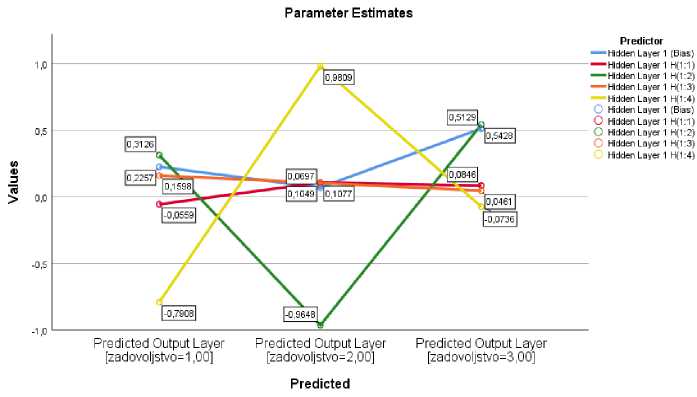

Figure 1 illustrates the predictive model with one hidden layer. A model with two hidden layers (deep learning) was also tested, but no significant improvement was observed compared to the single hidden layer model shown in Figure 1. The dataset was split into 74% training data (n = 77) and 26% testing data (n = 27). Figures 2 and 3 graphically display the activation function values for each input and hidden layer neuron (H1:1, H1:2, H1:3, H1:4) as well as the output layer. The same data split of 74% training and 26% testing was applied in these analyses.

Parameter Estimates

Predictor

— Input Layer (Bias)

Predicted Hidden Predicted Hidden Predicted Hidden Predicted Hidden

Layer 1 H(1:1) Layer 1 H(1:2) Layer 1 H(1:3) Layer 1 H(1:4)

Predicted

Figure 2. Graphical representation of the activation function for the input i hidden layer H(1:1), H(1:2), H(1:3), H(1;4)

Figure 3. Graphical representation of the activation function values for the output layer and the hidden layers H(1:1), H(1:2), H(1:3), and H(1:4).

Table 2 presents the model summary, that is, the accuracy of the predictive model for both the testing and training samples.

Table 2. Model summary

|

Training |

Sum of Squares Error Percent Incorrect Predictions Stopping Rule Used Training Time |

4,950 7,5% 1 consecutive step(s) with no decrease in error a 0:00:00,01 |

|

Testing |

Sum of Squares Error |

1,562 |

|

Percent Incorrect Predictions |

8,3% |

Dependent Variable: Satisfaction with the Quality of Collaboration with the Mentor a. Error computations are based on the testing sample.

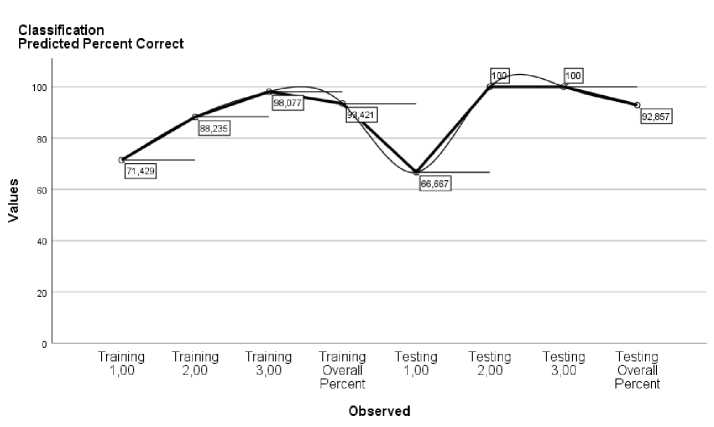

Table 2 shows that the prediction accuracy in the training sample is 92.5%, compared to 91.7% in the testing sample. The minimal discrepancy between the models indicates a high predictive validity regarding satisfaction with the quality of mentor collaboration. Classification accuracy is provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Classification

Predicted

|

Sample |

Observed |

1,00 |

2,00 |

3,00 |

Percent Correct |

|

Training |

1,00 |

5 |

2 |

0 |

71,4% |

|

2,00 |

2 |

15 |

0 |

88,2% |

|

|

3,00 |

0 |

1 |

51 |

98,1% |

|

|

Overall Percent |

9,2% |

23,7% |

67,1% |

93,4% |

|

|

Testing |

1,00 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

66,7% |

|

2,00 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

100,0% |

|

|

3,00 |

0 |

0 |

19 |

100,0% |

|

|

Overall Percent |

14,3% |

17,9% |

67,9% |

92,9% |

Dependent Variable: Satisfaction with the Quality of Collaboration with the Mentor

In the training sample, among those who completely agree (3), 51 were correctly classified, corresponding to a prediction accuracy of 98.1%. Only 1.9% of the responses in this category were misclassified as “partially agree,” representing the error rate. When examining all prediction errors across both the training and testing samples, accuracy levels range between 66.6% and 100%. Lower accuracy is observed in the testing sample within the category “strongly disagree.” The graphical representation of model accuracy is provided in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Accuracy of the predictive model

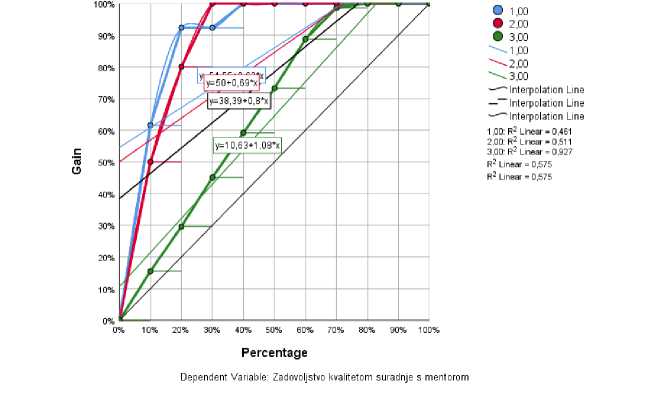

The area under the curve (AUC) for the dependent variable categories is 1 (0.963), 2 (0.970), and 3 (0.997), indicating an excellent balance between true positive rate (TPR) and true negative rate (TNR), i.e., between specificity and sensitivity. This means the model accurately identifies both correct positive and correct negative responses, with a low number of false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN). Additionally, Figure 5 presents the Gain*percentage graph, showing the proportion of each dependent variable category relative to the highest predictive accuracy in the data. Considerable discrepancies are observed: for category 3, 30% of positive cases are captured within the top 20% of results; for category 2, 80% of positive cases are captured; and for category 1, 92% of positive cases are captured.

Figure 5. Gain * percentage

Figure 5 illustrates the relative predictive importance of each individual variable with respect to Satisfaction with the Quality of Collaboration with the Mentor . The results indicate that the mentor relationship (KOMP 1) is the strongest predictor, while salary emerges as a more significant predictor of satisfaction than support from the principal or professional colleagues. This finding can be explained by the fact that salary reflects both an existential need and a status indicator within the profession. Consequently, it is unsurprising that salary exerts a greater influence on perceived satisfaction with mentor collaboration than support from the principal or professional colleagues.

Discussions

Novice educators need support during their entry into the profession. The quality of their professional development and future work will depend on whether they received support during their induction period. This study aimed to identify predictors of novice educators’ satisfaction in relation to their mentors. The results of the relative predictive importance of each individual variable on the value of Satisfaction with the Quality of Collaboration with the Mentor indicate that the relationship with the mentor (KOMP1) is the most significant predictor, while salary is a more important predictor of satisfaction than support from professional colleagues (KOMP2) and support from the principal (KOMP3). Support during the induction period is crucial for guiding novices into the profession. Most novices in the study by Mokoena and van Tonder (2024) faced significant challenges during their professional entry due to the absence of mentor support. Poor guidance of novices, ineffective communication, and lack of principal support were identified as key sources of dissatisfaction in the study by Louws et al. (2017) . Thornton (2024) , who examined mentors’ readiness for mentoring processes, found that many mentors working in educational contexts are insufficiently prepared for this role and suggests participation in programs that would prepare mentors for this process. The author believes that mentors could strengthen their knowledge during such programs and learn various strategies and methods for working with novice educators. In our study, participants rated principal support relatively high (M = 2.24; SD = 0.699), support from professional colleagues slightly lower (M = 2.20; SD = 0.655), while the mentor relationship received the highest rating (M = 2.45; SD = 0.660). Consistent with the findings of Schuck et al. (2018) , a high level of mentor support facilitates coping with the challenges inherent in the profession.

Walker and Kutsyuruba (2019) argue that encouraging novice educators to independently carry out tasks contributes to the development of self-efficacy, confidence, autonomy, and professional identity. Erawan (2019) warns that many novice educators leave the profession due to a lack of professional support, frequently facing behavioral challenges in children that they do not know how to manage, coupled with high workloads. Federičová (2021) emphasizes that approximately 45% of beginning teachers in European countries leave the profession entirely within five years of employment. Similarly, Ingersoll (2012) confirms that negative experiences during induction can lead to professional attrition, noting that 50% of novices exit the profession within five years if early experiences are negative. Considering these findings, our study included novice educators with work experience ranging from the first to the seventh year, confirming that satisfaction derived from the mentor relationship during the induction period positively influences later perceptions and overall job satisfaction. The effectiveness and quality of professional entry, induction, and subsequent work also depend on the characteristics of the novice educator. To successfully develop practical experience, a novice must demonstrate high motivation, enthusiasm, and a desire for learning, empathy and sensitivity in interactions with children, openness to constructive dialogue, flexibility in taking on various tasks, roles, and changes in the work environment, as well as responsibility, reliability, and willingness to engage in teamwork and collaboration.

Accordingly, the first years in the profession are crucial for novice educators to define themselves as professionals and continue their developmental trajectory with motivation. Otherwise, they may leave the profession, perpetuating the concerning trend that has become increasingly prevalent in recent years. Furthermore, our results indicate that the mentor relationship is the most significant predictor of novice educators’ overall satisfaction with the quality of collaboration with their mentor, whereas salary is a more important predictor than support from the principal or professional colleagues. In line with this, Darling- Hammond (2021) emphasizes that educational systems aiming to meet the demands of 21st-century teaching must not only recruit the best novices but also guarantee working conditions comparable to those of established professionals. This approach establishes professional norms that ensure status, salary, professional autonomy, and accountability. Motivation for entering the profession is often a combination of status, work environment, sense of personal contribution, and financial rewards ( OECD, 2005 ). Research by Farinde-Wu and Fitchett (2018) shows that job satisfaction correlates with teacher retention, which, in turn, positively affects the overall climate of the institution. Based on these findings, the authors conclude that job satisfaction can reduce teacher attrition. The mentoring process significantly shapes the professional development of novice educators and their perception of the profession, which consequently influences the formation of the professional culture within the institution.

Conclusions

Professional development of educators begins with initial education and continues with entry into the profession; therefore, the induction period is considered the most critical phase for guiding and retaining novices in the field. The mentor plays a pivotal role in shaping the professional identity of novice educators, making support within this relationship essential to ensure that novices receive timely information and assistance. Early childhood education practice is complex and dynamic, requiring well-prepared educators who have the knowledge, skills, and motivation to manage the challenges it presents. Trust, mutual respect, and regular communication are thus indispensable elements of effective mentoring relationships. The synergy between mentor and novice creates a stimulating environment for learning and development, directly influencing the ongoing growth of both the novice and the mentor. Conversely, the absence of support often results in novices leaving the profession, which, particularly in the current context, negatively impacts the quality of early childhood education institutions.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Faculty of Teacher Education at the University of Zagreb (ufzg-potp12-2025-IK), as well as the preschool teacher trainees who completed the survey questionnaires as part of the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Faculty of Teacher Education, University of Zagreb (ufzg-potp12-2025-IK).

Conflict of interests

The Authors declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

For more information in this regard, please see:

Institutional Review Board Statement

Prior to participation, informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were informed of the study’s objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits, as well as their right to withdraw at any stage without any negative consequences.

All ethical considerations were observed, including the confidentiality of personal information, voluntary participation, and data protection in accordance with applicable legal and institutional guidelines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K., A.V.; methodology, S.O.; software, S.O.; formal analysis, S.O.; writing— original draft preparation, T.K., A.V. and S.O.; writing—review and editing, T.K., A.V. and S.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.