Designing Language Activities for Young Learners Based on Human and AI-generated Stories

Автор: Ekaterina Sofronieva, Svetlana Gyuzeleva-Dimitrova, Christina Beleva

Журнал: International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education @ijcrsee

Рубрика: Original research

Статья в выпуске: 3 vol.13, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article presents the results of a study conducted among novice teachers of English language, trained at two major universities in Bulgaria. The objectives of the study were: 1) to evaluate the extent to which students perceived stories, authored by human and artificial intelligence, as applicable in educational context; 2) to gain an insight into their competence to design story-based language learning activities for preschool and primary school children; and 3) to seek possible relations between their teaching competence, language proficiency levels, skills to use AI-tools and their perceptions of the usefulness and practical classroom application of the two types of narratives. Results showed that students viewed both types of texts as useful in foreign language teaching, but the displayed degree of usefulness was stronger for the AI-generated one. A tentative explanation of this finding could be the capacity of ChatGPT as a large language model to mimic human linguistic production fairly convincingly. Overall, students exhibited a reasonably high degree of understanding of language learning as a collaborative experience and showed abilities to apply interactive approaches and techniques in the activities they proposed. The higher the teaching competence of the participants, the stronger their awareness of the various interdisciplinary links a teacher can make in their language classes to other fields of knowledge. This is a promising indication for the capacity of teachers to capitalize on the affordances of story-based language learning and interweave cross-curriculum references in their teaching practices which brings added value to the learning process.

Early language education, stories, activity design, artificial intelligence

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170211401

IDR: 170211401 | УДК: 37.091.3::811.111; 37.091.39:004.8 | DOI: 10.23947/2334-8496-2025-13-3-573-587

Текст научной статьи Designing Language Activities for Young Learners Based on Human and AI-generated Stories

The present study is part of a large research project launched among university students from different teacher training programmes at two Bulgarian universities - Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski” and New Bulgarian University, aimed at exploring different aspects of the use of stories, generated by human and artificial intelligence (AI), in language education. This study seeks to ascertain the potential applicability of AI-created narrative texts in story-based language teaching practices. Designing activities, the contents of which stem from engaging stories, to achieve specific language learning purposes that are tailored to the needs of particular young learners, is at the core of interactive, learner-centered language classrooms.

Early language learning encompasses cognitive, affective and social aspects. Holistic approaches to teaching languages to children aim at engaging the entire personality of the child by devising communicative opportunities that promote the use of the target language ( Cameron, 2001 ; Pinter, 2017 ). Continued and meaningful input in the target language ( Gass and Mackey, 2015 ) fosters acquisition as it provides a communicative environment where learners, under gentle guidance, explore a new linguistic reality and gain self-confidence.

Language teaching practices that ensure an ongoing exposure of learners to the target language at a level surpassing their current output fluency prove beneficial for sustainable language progress ( Terzioğlu and Kurt, 2022 ). Instruction styles that encourage learners’ efforts to step beyond the current limit of lin-

-

*Corresponding author: e.sofronieva@fppse.uni-sofia.bg

-

© 2025 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

guistic resources available to them ( Gass and Mackey, 2015 ) provide a safe learning space for progress. It should also be noted here that frequent encounters with lexical and grammatical items facilitate their acquisition by young learners. A particularly efficient technique is the provision of a variety of contexts or discursive opportunities where these items are utilized ( Cameron and McKay, 2013 ). Additionally, creating diverse opportunities to communicate in the target language adds substance to incidental lexical gains ( Cameron, 2001 ).

Stories provide an engaging context for language learning ( Harizanova, 2020 ). Research shows that primary school children are better able to comprehend fiction narratives in comparison with nonfiction texts ( Chung et al., 2023 ). This finding is corroborated by viewing the language of stories as representational rather than merely referential ( Hsu, 2015 ). Lexical units and syntactical structure make better sense and are easier to retain ( Godwin-Jones, 2018 ) when placed in a cognitively and emotionally appealing contextual frame ( Ghafar, 2024 ; Goodger, 2025 ). This is further supported by evidence, suggesting that discursive practices in language classrooms step onto context as “the locus of language” ( Dodigovic, 2005: 4 ). Practices in early language teaching incorporating short narratives assist language acquisition by “increasing word knowledge or introducing different sentence patterns” ( Hadaway and Young, 2010: 45 ). Stories have been acknowledged to help increase children’s vocabulary range and awareness of sentence structure ( Mukherji and O’Dea, 2000 ) in their mother tongue as well. Furthermore, stories are also deemed to enhance oral production ( Arias, 2017 ) as they exemplify specific language patterns that young learners employ with a growing confidence in their own language output.

In the early stages of learning a foreign language, listening and speaking skills are the focus of instruction ( Arnold and Rixon, 2011 ). Listening to engaging narratives not only develops awareness of phonological characteristics of the target language but also supports comprehension of word meanings ( Valentini et al., 2018 ; Read and Soberón, 2020 ). Findings from a study among preschool children indicate that listening to stories is “beneficial to the development of oral language complexity and story comprehension in young children” ( Isbel et al., 2004: 161 ).

Findings from research among Taiwanese preschool children ( Hsu, 2015 ) show that engaging plots stimulate critical thinking skills and, additionally, keep learners with shorter attention spans interested in the activity, provided that teachers ensure continued constructive guidance. Further to that, well-designed language learning activities streamline the overall structure of pedagogical interventions ( Littlejohn, 2011 ). These observations are consistent with the view that vocabulary acquisition occurs not through direct instruction but rather through communicative exchanges which situate lexical uses in a specific context ( Elley, 1989 ). The power of the spoken word is further exemplified in the claim that children at primary school are better able to understand the meanings of new words when listening to stories rather than when reading them ( Valentini et al., 2018: 11 ). Research has shown that conversations with young learners as part of interactive read-alouds enable incidental word learning ( Cole et al., 2017 ) as the contextual framework helps children infer the meanings of unfamiliar lexical items ( Elley, 1989 ).

Story-based language activities are particularly effective when performed collaboratively since teamwork can foster communication and enhance learners’ creativity and problem-solving skills. Collaborative learning and group activities have been evidenced to improve the language progress of both individual learners ( Whong, 2011 ) and the entire group ( Moskovkin and Shamonina, 2020 ). Practising the language in small groups provides a safe environment where learners are encouraged to rely on already accumulated knowledge ( Cole et al., 2017 ) and scaffold their skills for social cooperation and joint decision making. Learning is supported by the interactive incorporation of various sensory prompts, physical movement and meaningful references to children’s own prior experience ( Goodger, 2025 ). Further to that, language learning activities that foster cooperation, celebration of achievement and inclusion impact learners’ confidence and, more importantly, provide a learning environment where children feel safe to take risks in their linguistic output ( Vygotsky, 1978 ; Cameron, 2001 ; Cameron and McKay, 2013 ). Some recent studies suggest that there are also ensuing linguistic benefits from a more active social engagement with peers while taking part in language learning activities ( Ghafar, 2024 ).

Language teachers can devise warm-up and/or follow-up activities, based on stories, that aim at revising or introducing new linguistic content. It is through well-designed, insightful and fun activities that young learners can be engaged in using the target language (Read, 2007; Goodger, 2025). Providing children with diverse contexts for language use empowers them to achieve a “more fluent automatic production” (Gass and Mackey, 2015: 185). To further promote linguistic output, it is considered beneficial to vary the communicative setting of language-learning activities, thus challenging learners to experiment with their communicative abilities (Daniel, 2012), as well as to expand the range of linguistic resources they employ (Cameron and McKay, 2013; Gass and Mackey, 2015). As learners gain confidence in their language progress, it would be worthwhile to engage them in activities aimed at an independent generation of contextual cues (Wen, 2021).

When designing a learning activity suited to learners’ needs, educators first consider specific teaching goals and expected outcomes. In the light of current learner-oriented teaching practices, it is of even greater importance to focus activities on language-learning purposes that are “clear and meaningful” ( Moon, 2000: 88 ) for the learners themselves. Young children are eager to make sense of activities they are invited to take part in, and it is this strive to construct meaning which can effectively be put into action in language learning ( Cameron, 2001 ).

The clear narrative structure of stories for young children provides a sustainable model for young learners, which supports a syntactically complicated ( Brinton and Fujiki, 2017 ) and logically consistent output, thus laying solid foundations for the development of narrative skills. Storytelling activities can help reinforce grammatical structures ( Fojkar et al., 2013 ; Arias, 2017 ) and enhance language complexity ( Isbel et al., 2004 ). Compared to participation in conversational exchanges, attempts at producing an oral narrative pose a much greater challenge to young learners’ abilities to plan and control their linguistic production ( Nicolopoulou, 2017 ), which nurtures the development of reflection-on-action learner strategies and learner agency, i.e. “the feeling of ownership and sense of control that learners have over their learning” ( Larsen-Freeman et al., 2021: 6 ).

The present study is also underpinned by the understanding that situates language teaching within the broader framework of educational values for children’s overall development ( Arnold and Rixon, 2011 ). Therefore, language classroom practices which expand functional language goals to include the fostering of skills and knowledge that formally belong to other subject areas or fields of learning ( Richards and Rogers, 2014 ) cultivate sustainable, meaningful and engaging pedagogical interactions. Designing language learning activities that endorse skills and concepts from other domains of knowledge ( Daniel, 2012 ; Mukherji and O’Dea, 2000 ) and develop associative thinking abilities ( Bland, 2021 ) adds value beyond the specific language-related goals of instruction. Additionally, language teaching is inherently meant to equip learners with competencies for intercultural communication ( Dimitrova-Gyuzeleva, 2019 ). Authentic short narratives can be effectively employed in language teaching to develop learners’ intercultural awareness ( Mukherji and O’Dea, 2000 ; Russel and Murphy-Judy, 2020 ; Bland, 2022 ).

Results from a survey among primary school language teachers in Turkey ( Çakir, 2015 ) indicate that teachers may be unwilling to develop their own instructional materials or activities for reasons related to curriculum content, time constraints, or lack of sufficient confidence in using digital technologies. Another study, conducted among primary school language teachers in Slovenia ( Fojkar et al., 2013 ), suggests that time constraints come again to the fore when instructors need to choose between adapted and authentic short stories, as well as between pre-created and self-created accompanying activities. We believe it would be worthwhile to research language teaching practices in Bulgarian educational settings for young children to gain insights into the degree to which language teachers feel confident and competent to apply interactive approaches and activities of their own design.

With regard to the rapid technological advancement that educational practices nowadays avail of, it would be pertinent to acknowledge the growing evidence of artificial intelligence (AI) tools’ usability for complementing language learning ( Sarwari et al., 2024 ; Woo et al., 2024 ). Educators’ choices of how to incorporate AI applications in teaching can benefit from precepts governing the usage of educational technology, such as “the educational value of the tools and applications […], how adequate they are in the acquisition of knowledge, whether there is an interaction between users and tools” ( Stošić, 2015: 112 ). In the field of language instruction, generative AI is deemed to be of useful assistance to language educators as regards the development of learning materials and tasks ( Öksüz Zerey, 2025 ). Moreover, AI systems can “gamify the classroom” ( Shah, 2023: 170 ) by suggesting entertaining activities that either serve to achieve particular educational purposes or ensure a more relaxed learning environment. Our study followed the line of thinking suggested by Murphy (2019) that AI systems or applications are currently better suited for generating predictable and less varied tasks, while complex ones are more efficiently designed by humans ( Chang and Kidman, 2023 ).

From the perspective of inclusive education, there is growing evidence that AI systems can “cre- ate tailored educational content” (Damyanov, 2024: 18) that takes into account diverse learning styles and needs. Additionally, the capacity of AI tools to provide personalized feedback on learners’ progress (Baltezarević and Baltezarević, 2024) has been increasingly acknowledged. Research findings also suggest that AI technologies can be effectively used to promote collaborative learning (Luckin et al., 2016) and conversational practices (Godwin-Jones, 2024). Therefore, implementing AI tools in educational contexts calls for strong awareness on the part of educators of the ethical aspects of AI use (Shah, 2023; Damyanov, 2024; Pack and Maloney 2024). Specific ethical concerns have been raised regarding the degree to which AI technologies are tailored to meet the developmental needs of young children (Berson et al., 2025).

Although there is a lot of research on the value of using stories to facilitate early language acquisition and support children’s general cognitive development, as well as on the learning affordances of educational technology, to our knowledge there have been no studies conducted to ascertain the potential applicability of AI-created narrative texts in story-based language teaching practices. The present study aimed to prove that AI-generated stories are as good as those created by human authors and can effectively be used in educational contexts, saving teachers a lot of time and effort in creating additional teaching materials.

Theoretical background of the study

The present study steps onto the sound theoretical and practical rationale of research on learning in the early years and early language acquisition, on the one hand, and the usability of AI-generated textual output in language instruction, on the other.

Socio-cultural theory and the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development

Our survey is underpinned by the constructivist perspective in education, which calls for active learning and positions the learner at the centre of the educational process. It is the basic tenet of the socio-cultural theory and underlies the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development proposed by social constructivist Lev Vigotsky (1978, 1997) . According to Vygotsky, cognitive growth in childhood is enhanced by interaction with and assistance from a skilled instructor or another significant adult. The Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is hypothesized to construe “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by the independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” ( Vygotsky, 1978: 86 ). A stimulating learning environment and active social interaction with peers and educators within the learning context are vital for cognitive growth. Lev Vygotsky argues that “learning awakens a variety of developmental processes that are able to operate only when a child is interacting with people in his environment and in cooperation with his peers” ( Vygotsky, 1997: 35 ). We perceive this concept as highly relevant to language learning, especially given the constructivist premise that working on tasks that challenge young learners’ capabilities, and yet are made achievable by proper guidance, provides substantial learning benefits within the ZPD. It is argued that successful learning within the ZPD is triggered by involving the children in problem-solving, open-ended tasks – rather than traditional ones with routine procedures and predetermined solutions – and scaffolding the learning experience for them ( Wood, Bruner and Ross, 1976 ). Following these principles, we invited the participants in our study to consider the cognitive benefits for young learners when designing language learning activities based on human- and AI-generated stories, so that they encourage collaboration and facilitate language progress within the ZPD.

Learning-centered, story-based language teaching

As far as language teaching approaches are concerned, we have chosen to design our study within the theoretical framework of using stories to encourage the development of language skills and active language production among young learners. In particular, we have followed the understanding of the holistic, learning-centered approach to language instruction (Cameron, 2001), which highlights the usage of stories as engaging educational resources for children as well as a basis for the design of targeted tasks and activities (Cameron, 2001; Arias, 2017). What we perceive as particularly valuable in Cameron’s theoretical and practical perspective to early language learning are the clearly outlined aspects of making efficient use of stories in language classrooms. These aspects range from choosing tales which engage young learn- ers and, more importantly, offer “space for language growth” (Cameron, 2001: 167) in terms of content, plot organization and use of language, to devising learning activities, based on stories, that support the development of different language skills. Additionally, we have chosen to adhere to the premises of the interactionist approach (Gass and Mackey, 2006, 2015) to language learning, where learners’ output is actively promoted through interventions that provide meaningful input and feedback. Encouraging young learners to use the foreign language is viewed through the perspective of cognitive and social factors, affecting interaction (Gass and Mackey, 2006, 2015), so that the latter be conducive to language acquisition.

In the Companion Volume to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (2020), this focus on an active, action-oriented approach to language learning is even more pronounced and emphasized than in the original document of 2001 (although there, too, an entire chapter is devoted to the characteristics of language tasks and their role in language teaching). What is also worth noting is that the CEFR Companion Volume (2020) adds another level preceding the lowest level of language proficiency (pre-A1) to reflect the desire for an early start in foreign language learning and acknowledge what young learners can actually do with the language they have acquired. In this train of thought, we believe that even young children of preschool age with a limited vocabulary may successfully cope with the functional acquisition of the target language, capitalizing on the affordances of the Zone of Proximal Development ( Vygotsky, 1978 ) under the support of skilled language instructors. Based on these tenets, the participants in our study were invited to design story-based action-oriented tasks and activities suitable for interactions with young learners in the foreign language classroom.

Use of generative AI in language instruction

As far as the usability of AI-generated textual output is concerned, our study stems from the well-grounded theoretical assertion that generative AI systems and tools, such as ChatGPT, are increasingly capable of producing coherent texts which are lexically and grammatically fluent ( Chu and Liu, 2024 ; God win-Jones, 2024 ; Shah, 2023 ). Additionally, the linguistic aspects of AI-written output have been found to imitate closely those of human-created texts ( Shah, 2023 ). We fully endorse the conclusions from recent research that highlight generative AI as complementary to human teaching capacity since “effective material development requires the consideration of the teaching context, student needs and interests, and course objectives - factors that AI alone cannot fully account for” ( Öksüz Zerey, 2025: 153 ).

Within this theoretical framework, our study seeks to gain insight into the usability of AI-generated tales for the design of language-learning activities, as well as for enhancing young learners’ language progress. Therefore, both a human-authored and an AI-generated story have been employed in the methodological task assigned to the study participants. In that light, we have tried to bridge the existing gap in literature and research which have so far primarily focused on human-authored stories in early foreign language education. We believe that AI-generated stories for children have certain potential and teachers can take advantage of the available AI tools to help them generate quality teaching materials.

Materials and Methods

This study took place in the months of November 2024 - January 2025. Students from several programmes in English studies and foreign language teaching offered at two major Bulgarian universities were invited to participate in it on a voluntary basis. The Moodle e-learning platform was used for data collection. The results from the subsequent analysis of teacher trainees’ views on the use of human-written and AI-generated narratives in designing activities suitable for young learners’ foreign language development are presented and discussed in this article.

To fulfil the objectives of our study, participants were tasked to carefully read two children’s stories (one human-authored and one AI-generated) and assess some specific language learning and teaching implications related to them. The particular origin of the texts was not disclosed to the participants. Supplementary, they were further instructed to design language activities for preschool or primary school children based on the two narratives. The teaching goals for each of the suggested activities had to be outlined and justified.

The research questions participants needed to respond to in order to report on their perceptions of the usefulness and practical classroom application of the two stories were the following:

How useful is each story for developing young learners’:

-

• foreign language comprehension? (Q1);

-

• foreign language production? (Q2);

-

• vocabulary in the new language? (Q3);

-

• grammar in the new language? (Q4);

-

• communicative skills? (Q5);

-

• narrative skills? (Q6);

-

• skills to elaborate their own fractured tale? (Q7).

How easily can each story be taught with reference to other fields of knowledge (i.e. interdisciplinary links)? (Q8). How easily can each story be taught in an inclusive way, appropriate for intercultural classrooms? (Q9). How can we use human-authored and AI-generated stories in early foreign language learning? (Q10). For Q1-Q9, students could opt for 1 - “not at all”, 2 - “slightly”, 3 - “moderately” or 4 - “very” when assessing the usefulness of the two narratives on the first nine survey items.

The last item in this section of the survey (Q10) was intended as a methodology assignment which aimed at triggering students’ creativity and raising their teaching competences. As has already been mentioned, they were encouraged to create educational content for classroom interactions with young learners.

Additional data on students’ self-assessed skills and competences were collected. Teaching competences, manifested in their capacity to design educational content, language proficiency and abilities to use AI tools were measured on a 5-point Likert scale with possible responses ranging from 1 to 5 (1-minimal, 2-average, 3-good, 4-very good, 5-excellent). We decided on a self-reported measure as an alternative to external evaluation based on the premise that the participants’ self-reflection and sense of personal knowledge, experience and qualifications are a reliable indicator and should be accounted for.

Two stories were selected to best address the objectives of the study. As mentioned above, the origin of the texts – human-authored or AI-generated – was not revealed to the students.

The rationale behind our choice of the human-authored story (referred to as Story A in the research questionnaire) had several aspects. First of all, we sought an authentic and fairly short text whose linguistic characteristics would match the comprehension level of primary school learners of English and, at the same time, enable them to expand their vocabulary and syntactical range (Gass and Mackey, 2015). Additionally, we aimed at selecting a story with a very clear narrative structure that would be consistent with what young learners have been accustomed to in their own experience with story engagement so far. The clarity and predictability of a story structure further facilitate comprehension (Hadaway and Young, 2010) while reinforcing awareness of how a narrative develops and how its elements are arranged. Thirdly, the selection of the human-authored text followed the premise that the usability of a story for educational purposes is related to its potential to engage learners both cognitively and affectively (Tomlinson, 2003). Thus, the human-written narrative for young learners was selected from among the variety of stories, offered as resources to English language teachers and parents in the LearnEnglish Kids section of the British Council’s website

The AI-generated story (referred to as Story B in the research questionnaire) resulted from an uninterrupted written interaction with ChatGPT-3.5, which occurred on 19 November 2024 from 19:20 hrs to 19:27 hrs. The prompts suggested to the generative AI model were devised in advance and referred to the following expected output characteristics: target audience, length of text, and key plot elements. No additional cues as regards the overall playful tone or action-driven orientation of the solicited content were suggested. The initial output from ChatGPT-3.5 was deemed satisfactory as it corresponded reasonably closely with the above linguistic, structural and engaging characteristics of the selected human-authored narrative. The perceived fluency and narrative consistency of the AI-generated output were congruent with findings from other studies ( Shah, 2023 ; Godwin-Jones, 2024 ; Chu and Liu, 2024 ). Thus, we chose to submit no additional prompts to ChatGPT-3.5, seeking to adjust its initial written production.

A brief linguistic comparison between the human-authored and AI-written story provides additional insights. The human text is predominantly organized as a conversational interaction between the main characters, while the AI text follows a more descriptive, linear narrative development. Furthermore, the name of the pirate captain in the AI-generated story (‘Blackbeard’) conforms with the context very adequately and mirrors the captain’s name in the human-authored text (‘Redbeard’). Thus, ChatGPT displays the capacity to match its linguistic output to specific contexts in a consistent, yet predictable and unoriginal way.

The scripts of the two narrative stories are presented herein below.

Story A

Sanjay saw a bottle floating in the sea. There was something inside it. He took it out.

‘What is it?’ asked Sarah.

‘It’s a map! It’s a map!’

They looked round and saw a talking parrot.

‘Buried treasure! Buried treasure!’

‘Wow! A treasure map! Let’s follow it.’

‘Maybe it’s gold!’

‘Or silver?’

‘Or jewels?’

‘OK. We are here and the treasure is here.’

‘Let’s go! I’ll read,’ said the parrot. ‘Walk 80 metres north.’

‘1, 2, 3 … 78, 79, 80.’

‘Turn right at the big coconut tree and go straight on until the crocodile pond. Cross the bridge, turn left and keep walking. Turn right in front of the big, round rock. Walk straight ahead for 50 metres.’

‘1, 2, 3 … 48, 49, 50.’

‘Go through the cave. Mind the bats! Mind the bats! Walk straight on until the beach. Go along the beach for 200 metres. The treasure is behind the square rock. Over there! Over there!’, the parrot shouted.

‘It’s empty!’ cried Sarah.

Inside there was an old note.

Dear Finder, Sorry, but I took my gold. I needed to buy a new pirate ship. Bye, Captain Redbeard.

‘Well, at least we had a nice walk,’ said Sanjay.

‘Yes, and we made a new friend!’

Story B

One sunny afternoon, siblings Mia and Jake played in their backyard when Jake tripped over a rusty tin box buried under a tree. Inside, they found an old, crumpled map marked with a big red X. ‘A treasure map!’ Mia exclaimed.

The map led them to the forest nearby. As they puzzled over the directions, a squawking voice startled them. ‘Treasure? Follow Polly!’ A colourful parrot flapped down from a tree.

‘You know where the treasure is?’ Jake asked. The parrot bobbed its head. ‘This way! This way!’

Polly led them through the winding forest paths, over a stream, and up a hill. Finally, they reached a small clearing where an ancient chest lay half-buried in leaves.

Excited, the children lifted the heavy lid, only to find the chest empty - except for a yellowed note. It read:

‘To those who find this treasure, the real prize is the adventure you’ve had. Welcome to the crew! -Captain Blackbeard.’

Jake and Mia laughed.

‘We didn’t get gold,’ Mia said, ‘but we found Polly!’

Polly fluffed her feathers proudly. ‘Best treasure ever!’ she squawked.

And from that day on, the three friends were inseparable, ready for many more adventures.

Results and Discussion

We used the statistical package for social sciences IBM SPSS Version 23.0 for both descriptive and inferential statistics in the analysis of data. Mean and standard deviation of scores were computed to offer a picture of the set results as a whole, i.e. show the central tendency and the extent to which individuals in the group deviate from it. Further, paired sample t-test analysis was used to compare group differences of students’ responses in relation to the extent to which they had assessed the usefulness of the two types of texts in early language education of children. Finally, Pearson correlation coefficient measure was employed to test if the registered differences in students’ teaching competence, language proficiency and use of AI levels would influence their valuation of the two types of texts.

Participants

Our selection of participants was a non-random convenience sample which is used in “most research in psychology” ( McBurney and White, 2007: 248 ).

Two hundred and ten students (N=210) participated in the study. They represented the entire population of the students on the language teaching programmes at the universities. An overall high return rate of over 90.0 percent was recorded, which is indicative of participants’ interest in the tasks proposed in the survey. The great majority of the students were females (N=196) and this did not come as a surprise for females have always predominated on teacher training university programmes. Students’ mean age was 26.5 years. All participants had a good command of the English language and their proficiency level was above B1 (CEFR). What is worth noting is that among the participants, there were 18 international students from Austria, Spain, Greece, and Italy who were studying in Bulgaria on the Erasmus exchange or other programmes, as well as a couple of bilingual native speakers of English and Bulgarian.

Procedures

Usefulness of the two stories

First, to address research questions Q1-Q9, participants were asked to evaluate the extent to which they perceived the two stories useful for the development of different aspects of young learners’ language skills and competences on a 4-point Likert scale. A summary of the results is offered in the table below.

Table 1. Mean and standard deviation of participants’ responses

Usefulness of each story for the development of Narrative text Mean Std. Deviation children’s:

|

language comprehension (Q1) |

Story A Story B (AI text) |

3.19 3.23 |

0.741 0.771 |

|

language production (Q2) |

Story A |

3.15 |

0.710 |

|

Story B (AI text) |

3.20 |

0.785 |

|

|

vocabulary (Q3) |

Story A |

3.25 |

0.731 |

|

Story B (AI text) |

3.49 |

0.672 |

|

|

grammar (Q4) |

Story A |

2.88 |

0.772 |

|

Story B (AI text) |

3.37 |

0.715 |

|

|

communicative skills (Q5) |

Story A |

3.21 |

0.770 |

|

Story B (AI text) |

3.07 |

0.785 |

|

|

narrative skills (Q6) |

Story A |

2.94 |

0.819 |

|

Story B (AI text) |

3.37 |

0.792 |

|

|

skills to elaborate their own fractured tale (Q7) |

Story A |

3.01 |

0.874 |

|

Story B (AI text) |

3.40 |

0.757 |

|

|

interdisciplinary skills (Q8) |

Story A |

3.11 |

0.826 |

|

Story B (AI text) |

3.05 |

0.871 |

|

|

intercultural skills (Q9) |

Story A |

3.17 |

0.771 |

|

Story B (AI text) |

3.12 |

0.845 |

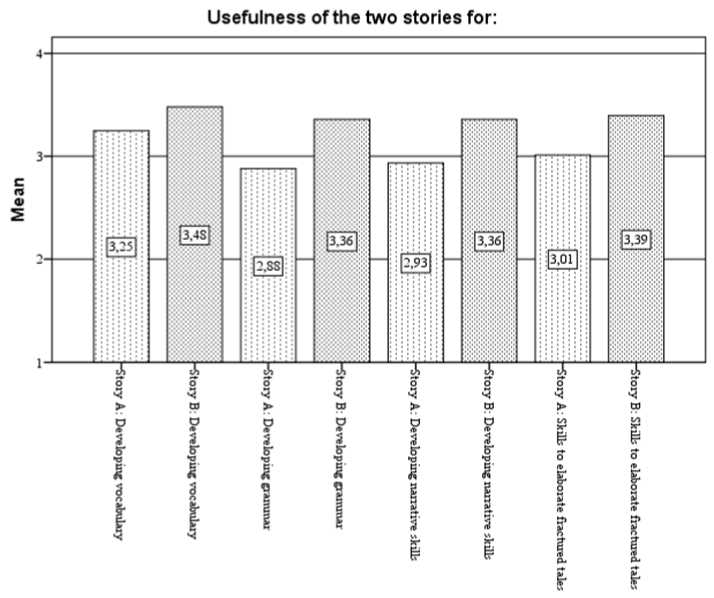

As is seen, the usefulness of text B in most designated aspects of language education was perceived by trainee teachers as more robust compared to that of text A. We used paired sample t-test to further check the strength of the registered group differences. Analysis revealed four areas in which the AI-generated story strongly outperformed the human-authored one, with the corresponding differences being statistically significant (i.e. for “developing vocabulary in the new language”: t= -3.425; df= 209; p = 0.001; for “developing grammar in the new language”: t= -6.641; df= 208; p = 0.000; for “developing young learners’ narrative skills”: t= -5.287; df= 202; p = 0.000; and for “fostering young learners’ skills to develop their own fractured tale”: t= -4.999; df= 204; p = 0.000). Graphical representation of the results follows:

Figure 1. Statistically significant differences in students’ perceptions regarding the usefulness of the two stories for the development of different aspects of young learners’ language skills and competences.

The above aspects of perceived language-learning usability of story B can be viewed in the light of the increasing fluency of AI-generated output ( Shah, 2023 ; Godwin-Jones, 2024 ). Our own experience with written and oral exchanges with ChatGPT confirms the capacity of this large language model to mimic human linguistic production fairly convincingly.

These findings of our study indicate clearly that the AI-authored story is regarded by novice teachers as an educational material which can positively impact the development of young learners’ lexical, grammatical, narrative and narrative-transformative skills. The results strongly suggest that AI textual output, which has been carefully curated to meet specific language learning goals, can successfully complement teaching materials. Previous research on incorporating human-authored tales in language learning yields similar benefits for children’s linguistic output ( Isbel et al., 2004 ; Gass and Mackey, 2015 ; Nicolopoulou, 2017 ; see also Brinton and Fujiki, 2017 ; Fojkar et al., 2013 ; Wen, 2021 ).

Proposed language activities

To address our research question 10 (Q10), we next invited students to create foreign language content for young learners based on the two stories.

Among the proposed students’ methodological designs which aimed to foster children’s comprehension, production and communicative skills in English were different treasure hunt simulations, various roleplays and acting out activities, teamwork suggestions, etc. Changing the script/plot of the story, inventing short dialogues between different characters, transforming the tale to add a new adventure or story character were brought up as useful tools and techniques for developing young learners’ narrative skills and skills to elaborate their own fractured tale. Sample activities of using stories for developing children’s vocabulary and grammar in the new language were somewhat more traditional. They encompassed introducing and reinforcing specific vocabulary, e.g. directions (north, south, east, west), measurements (meters), the natural world (sea, bottle, coconut tree, crocodile pond, forest, stream, hill), emotions (excited, disappointed), etc. Interdisciplinary skills were also involved in view of specific vocabulary. Grammar included categories like past tense verb forms, prepositions, etc. Crosswords, quiz games, bingos, etc. were among the suggested fun language activities. Finally, activities encouraging inclusion of all children and enhancing their comprehension and production ranged from joint visual representations of the sto- ries, counting aloud, following commands, singing and dancing together. On the whole, participants in the study displayed a fairly high degree of understanding of language learning as a collaborative experience.

In summary, there has been a wide array of students’ proposals for various ways of incorporating each story in creative language learning activities for children. We could not possibly account for all instances and exhaust the matter in depth for these methodological designs need to be systemized and categorized in a structured way which is beyond the scope of the present paper. Yet, it will be fair to conclude that teacher trainees have displayed a great deal of enthusiasm, engagement and creativity in their ventures, trying to bridge different theories and practices in their classroom interaction with children. The study participants viewed both texts as appropriate and useful in the foreign language education of children, despite the perceived overall advantages of the ChatGPT-generated story for language teaching purposes. They appreciated different features in both stories: the appeal for young learners of the two action-oriented plots, rich in humorous twists and reflective messages on friendship and adventure. The latter are highlighted in most teacher trainees’ responses and subsequently reflected in their proposed creative methodological designs.

To illustrate participants’ performance in the assigned task, we offer below samples of two designs of language learning activities, one by a bilingual foreign student and one by a Bulgarian student. As is seen in the examples, both the human and AI stories can be successfully used as the basis for a treasure hunt-themed activity, aimed at learners of different ages.

Two case studies of students’ proposals for language learning activities for children

Task prompt: Suggest a way of incorporating each story into the design of a language learning activity for primary school children. When designing the activities, have in mind particular teaching goals. Outline each activity in the appropriate space below. Indicate learners’ age for each activity.

Design 1 (by participant No 73)

STORY A STORY B

Activity: Picture sequencing &retelling

Age Group: 6-8 years old

Goal: Improve listening and speaking skills

How it works : The teacher provides pictures representing key moments from the story. Children listen to the story, then work in groups to arrange the pictures in the correct order. Afterward, they retell the story using simple sentences, practising vocabulary and sentence structure.

Teaching goals :

Help kids understand spoken English by listening to the story;

Teach them how to put events in order so they follow the story correctly;

Let them practise speaking by retelling the story in their own words;

Introduce new words related to the story to enrich their vocabulary.

Activity: Treasure hunt & new vocabulary

Age Group: 7-9 years old

Goal: Learn new vocabulary and practise giving directions

How it works : After reading the story, children are given a “treasure map” with clues written in English. Each clue contains a simple instruction (“Go two steps forward and look under the chair”). They must follow the directions to find small “treasures” (stickers, flashcards, or small toys). This activity helps reinforce prepositions of place, action words, and storytelling elements.

Teaching goals :

Make learning fun by using a treasure hunt to teach directions;

Teach words like “under”, “next to” and “behind” through movement and actions;

Encourage teamwork by having students work together to find clues;

Improve thinking skills by using simple puzzles or step-by-step instructions.

|

Design 2 (by participant No 114) |

|

|

STORY A |

STORY B |

|

Activity : Treasure hunt simulation |

Activity : Parrot story creator |

|

Age : 6-7 years old |

Age : 8-10 years old |

|

Steps : Create a large map in the classroom or playground resembling the one in the story. Include landmarks like a coconut tree, crocodile pond, and cave. Read the story aloud, pausing at the directional commands. Ask learners to follow these directions on the map to find a hidden “treasure chest”. Once they reach the “treasure”, have a group discussion about what they found and practise new vocabulary (e.g. north, straight, left, right). |

Steps : Discuss the parrot’s role in the story and its humorous comments. Have learners work in pairs to invent a short dialogue between the parrot and the children, imagining a new adventure. Each pair presents their dialogue to the class, focusing on using expressive language and incorporating humor. |

|

Teaching goals : Develop comprehension of directional language; Practise action verbs (walk, turn, cross); Encourage teamwork and active participation. |

Teaching goals : Develop conversational skills and creativity; Practise forming sentences and using vocabulary in a playful context; Build confidence in speaking and presenting. |

The above samples are indicative of the comparable potential of both AI-generated and human-written stories to serve as a pedagogically appropriate basis for the design of language learning activities. Secondly, participants in our study adopted an increasingly multidimensional and age-appropriate approach to activity design to promote language use via the active involvement of young learners. The suggested methodological designs are strongly aligned with the understanding that empowering learner agency in young children ( Isbel et al., 2004 ) is at the core of material selection for language classrooms and activity design to support language progress ( Larsen-Freeman et al., 2021 ). Furthermore, the samples of novice teachers’ designs of language learning activities exemplify the current views of early language teaching as a set of communicative, playful and enjoyable practices that aim higher than the acquisition of mere functional literacy ( Harizanova, 2020 ; Bland, 2022 ). Sparking the curiosity and the sense of delight in young learners can be best achieved through narratives whose cognitive and emotional complexity prevails over the linguistic one ( Tomlinson, 2003 ). Additionally, the suggested activity designs highlight the benefits of engaging young learners in joint pursuits that incorporate sensory and physical stimuli along with collaborative communication, thus adding to the affective and social meaningfulness of language instruction. This methodological aspect of the study findings echoes views of group learning as promoting general learning strategies ( Cole et al., 2017 ) and making language progress durable, as well as emotionally satisfactory ( Bland, 2022 ; Nilsson, 2025 ).

Students’ teaching competence and skills

Finally, our last study objective was to seek for meaningful relations between students’ self-reported teaching competence, language proficiency, and skills to use AI tools on the one hand, and on the other hand, their perceptions of the usefulness of the two stories for enhancing second language use in young children. Means and standard deviation scores were computed for the studied variables. Results showed that students had assessed their competences and skills moderately high (for teaching competence: mean 3.15, std. dev. 0.96; for language proficiency: mean 3.70, std. dev. 0.81; and for skills to use AI tools: mean 2.84, std. dev. 1.05). All means were above or close to the midpoint of 3.00, and it was quite expected that the language proficiency and teaching competence of teacher trainees would outweigh their AI usage skills.

Pearson correlation coefficient revealed meaningful relationships between students’ teaching competence and their perceived usefulness of story A (the human-authored narrative) for developing young learners’ grammar (r =0.146*; p = 0.04) and building up communicative skills (r =0.172*; p = 0.01) in the new language. Such correlations were not found significant in relation to the AI-generated narrative.

Students’ competence also correlated positively with their assessment of the degree of ease to teach both stories with reference to other fields of knowledge (for story A: r =0.172*; p = 0.01); (for story B: r =0.177*; p = 0.01). The higher the experience of the students in designing language learning activities, the stronger their awareness of various interdisciplinary links to other fields of knowledge (e.g. maths, geography, the natural world, etc.) they could make using both texts in their classroom interaction. This finding holds promise for language classrooms in Bulgaria as the capacity to interweave cross-curriculum references in language teaching brings added value to the learning process. Designing language-learning tasks to empower not only confident language command but also to support the development of skills and knowledge in extra-linguistic areas has been proven a beneficial practice ( Arnold and Rixon, 2011 ; Daniel, 2012 ; Richards and Rogers, 2014 ).

On the other hand, students’ language proficiency was not correlated to any of the studied constructs which means that students’ evaluation of the usefulness of the two texts in foreign language teaching does not depend on how proficient they are in that foreign language. It should be noted, though, that teacher trainees’ proficiency in English was above level B1, which is one of the state requirements for obtaining the foreign language teacher qualification. In this sense, the study participants’ views can be regarded as reasonably objective.

Finally, students’ skills to use AI tools correlated positively with their perceptions of the usefulness of story A for developing young learners’ vocabulary (r =0.146*; p = 0.04) and communicative skills (r =0.153*; p = 0.03). Once again, interestingly, these correlations were statistically significant only in relation to the human-authored text. The tentative interpretation of this finding we can offer is that the more skilled interactions with AI tools – in particular, large language models, such as ChatGPT – attune the users to the stylistic constraints of their fluent, yet often unoriginal, output.

Conclusions

The study confirmed the usability and the potential of both AI-generated and human-authored narrative texts as complementary resources for early language learning. In particular, the applicability of AI-written stories for the development of meaningful and interactive language learning activities has been convincingly highlighted in the results from this survey conducted among trainee teachers of English. Furthermore, AI-generated and human-authored narrative texts were perceived as comparably conducive to the promotion of both linguistic and general cognitive and social skills in young language learners. These findings corroborate the specific theoretical framework of language learning and usability of AI systems in language education, underpinning our research. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, these methodological perspectives have not been previously addressed in research and broaden the existing approaches to using AI-generated output in early language instruction.

An additional finding that merits highlighting with a view to research on early language learning is the established positive correlation between novice language teachers’ experience in activity design for language learning purposes and their ability to relate young learners’ linguistic skills to other, extralinguistic areas of knowledge. This resonates with the strive for holistic, learner-centred pedagogies in language education.

Limitations of the present study, both theoretical and practical, need to be properly acknowledged. Firstly, the survey was conducted among novice language teachers. Secondly, the language of the sources that we have referred to is predominantly English, which reduces the scope of available research that may be relevant to the chosen topic. Furthermore, our study collected and analyzed self-reported data which calls for caution as to the generalizability of the findings.

We believe that further exploration of how AI output or AI tools can be meaningfully used in language instruction merits continued highlighting. Further to that, identifying ethical guidelines for the responsible employment of AI systems in educational practices will be of significant value.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the participants in this study.

Funding

This study is partially financed by the European Union - NextGenerationEU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project Sofia University Marking Momentum for Innovation and Technological Transfer (SUMMIT) № BG-RRP-2.004-0008-3.3.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in full compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional Review Board approval was not required since the study did not approach human participants in any interventional way and no vulnerable subjects or groups were involved. All participants were adult university students who took part in the survey on a voluntary basis. Informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. Minimal risk for research respondents was ensured. Fully anonymized datasets were used which do not allow participants to be traced.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, E.N.S., S.G.D.-G. and C.N.B.; methodology, E.N.S., S.G.D.-G. and C.N.B., software, E.N.S., formal analysis, E.N.S., S.G.D.-G. and C.N.B., writing—original draft preparation, E.N.S., S.G. D.-G. and C.N.B., writing—review and editing, E.N.S., S.G.D.-G. and C.N.B.; funding acquisition, E.N.S.; supervision, E.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscriptf.