Perceptions of project-based learning by Russian non-linguistic students’ in developing speaking skills in a foreign language

Автор: Kolegova I.A., Nguyen My.V.

Рубрика: Непрерывное образование в течение жизни. Образование разных уровней

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.16, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

In the context of higher education, one of the main goals of teaching English is to enhance students' ability in oral communication. Therefore, in order to study the language thoroughly, it is important to provide students with opportunities for regular practice outside of the classroom. An effective solution could be the use of project-based learning. Over the past decades, empirical studies in various countries have focused on the positive impact of project-based learning. However, there is little attention in the theoretical literature to the study of Russian students' perception of project-based learning.The article explores key aspects of teaching a foreign language using project-based learning at the Institute of Natural and Exact Sciences at the South Ural State University. The research studies Russian students' perception of project-based learning in non-language majors in developing oral English skills. The following tasks were set: to develop a model of project-based learning, to evaluate students' perception of this model when implemented in practice.The following theoretical and empirical methods were applied in the research: analysis of modern pedagogical and methodical literature, questionnaires, individual interviews, mathematical processing of the obtained data.The results showed that a majority of Russian students viewed the integration of English language classes and project-based learning positively. The interviews revealed some problems that students faced in project preparation, which require further investigation. The findings can help English language teachers effectively implement project-based learning for the development of speaking skills.

Learner-centered approach, non-linguistic students, project-based language learning

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147243650

IDR: 147243650 | УДК: 378.147.88 | DOI: 10.14529/ped240203

Текст научной статьи Perceptions of project-based learning by Russian non-linguistic students’ in developing speaking skills in a foreign language

I.A. Kolegova^, , Nguyen, , Ural State University, Chelyabinsk, Russia

И.А. Колегова^, , В.М. Нгуен, , Южно-Уральский государственный университет, Челябинск, Россия

In the context of higher education, one of the primary goals of English teaching programs is to enhance the students’ ability to communicate orally. In fact, there are some problems in teaching speaking skills, especially in the context of English as a foreign language (EFL). For example, students are unmotivated in learning and lack confidence in English communication in class due to low level of English proficiency [23]. Furthermore, students have fewer opportunities for regular practices of English beyond the class [30]. To enhance the effectiveness of Englishspeaking, consequently, it is essential to provide students with great opportunities for the regular practices beyond classrooms. In line with the discussion, the use of project-based language learning (PBLL) might be an effective solution. Over the past decades, various empirical studies have been devoted to the positive impacts of PBLL. In the Thai context, the students believed that PBLL helps them to apply both their specificmajoring knowledge of Information Science and English skills to deal with real-world problems [29]. From the perceptions of Malaysian students of English, the implementation of PBLL activities enhances their oral communicative competence [1]. In the Russian context, learning Eng- lish through PBLL not only enables engineering students to apply the engineering knowledge in the learning process but also significantly improves their oral and written communication [20, 22]. In a most recent study by Slabodar [31], the teachers recognize that students can enhance their self-confidence and English-speaking skills.

In today’s contexts of English education, developing the students’ speaking skills is increasingly becoming the center of learning outcomes in most schools [10]. In order to enhance the students’ English-speaking skills in the EFL context, it is essential to implement pedagogical approaches that effectively maximize the meaningful use of English in each lesson and help students to maintain the regular practices of English beyond classrooms [26, 27]. In response to this pedagogical requirement, learning activities should be focused on group work (GW). As stated by Chappell [12], GW might regularly prompt interactions in person among students. In the language classrooms, as commented by Richard [30], students in GW are profoundly engaged in the meaningful use of target language (L2). In line with the discussion, the use of the communicative language teaching approach (CLT) seems to be an ideal choice. Throughout its history, the use of CLT is mainly for developing the students’ communicative competence. As mentioned in most scholar research in the terms of CLT (e. g., Littlewood [23], Richards [30]), communicative competence is the overlap between grammatical competence (i. e., knowledge of language rules) and sociolinguistic competence (i. e., the use of language in society) with aspects of cultural competence. However, it is also necessary to consider contributing factors that influence the effectiveness of CLT implementation in real-life classrooms.

Regarding the implementing sequence of CLT activities, the functional communication activities should be firstly undertaken in classrooms of English-speaking skills. For instance, after lessons of English grammatical structures, students should practice English through pair activities (information gaps, interviews, picture comparison, etc.), mingling activities (any number of participants: e. g., signature game), or roleplays (any number of participants, depending on the situation). Littlewood [23] suggests that these activities enable students to use the language they know to understand meaning as effectively as possible. Subsequently, students need to practice English through social communication activities. These kinds of activities help students to effectively explore meanings and how to suitably use language in the social context. In most situations, communicative activities in teaching English speaking skills should be organized as a process of information transfer. To be more specific, an effective speaking activity should contain an information gap. As defined by Richard [30, p. 17], an information gap “refers to the fact that in real communication people normally communicate in order to get information they do not possess”. To illustrate this, teachers should organize small group activities (e. g., debates in groups, decision-making, or consensus activities) for students to use English meaningfully and purposefully.

Because of the varieties of English in a world context, it is important to consider the issues of what language contexts should be provided for students to effectively use in real-life social interactions. For the educational practices, the in-structionalization of language social interactions might be acceptably compatible [21]. In our research, this term is defined as modeling common language structures of social interactions in learning materials for English-speaking classrooms. In other words, the teachers firstly introduce some verbal communicative strategies to students, which include common language structures in the native speakers’ daily conversations. Besides, students need to regularly practice these strategies through communicative activities, i. e., working in small groups or pairs, inside classrooms.

Another aspect of English-speaking teaching in the EFL context is to focus on fluency or accuracy in the process of oral communication. As we may know, theories of CLT emphasized originally on the fluency of using language. However, it is criticized that speaking fluently without a certain amount of accuracy is not fluent at all. Indeed, in real-life communicative interactions, lack of accuracy might affect the comprehensibility and intelligibility that students of the English language express. Nevertheless, the teacher should not focus mainly on accuracy when teaching speaking English. To be more specific, the teachers’ intention should be “good” enough, which probably reflects the balanced focus of accuracy and fluency in classrooms of English speaking. In this sense, error correction in speaking English should be also focused on the errors that seriously affect understanding [17]. In the pedagogical practices, students can be more fluent in speaking in case that teachers use material that is familiar to them [6]. From this perspective, the teacher should design appropriate learning materials which include grammar or vocabulary they have already learned.

Moreover, the teacher supported the students to deal with the possible problems to complete their projects on time.

Materials and Methods

We used methods of convenience sampling to choose a research sample for the experimental teaching and data collection.

Table 1

Students’ background information

|

Categories |

Frequencies |

Percentages |

|

Gender |

40 |

100% |

|

Males |

32 |

80% |

|

Females |

08 |

20% |

|

Year of study |

40 |

100% |

|

Year 1 |

40 |

100% |

|

Academic major |

40 |

100% |

|

IT and Mathematics |

40 |

100% |

|

Year of English learning |

40 |

100% |

|

More than 05 years |

30 |

75% |

|

Less than 05 years |

10 |

25% |

|

English proficiency |

40 |

100% |

|

A1 – A2 |

0 |

0% |

|

A2 – B1 |

0 |

0% |

|

B1 – B2 |

40 |

100% |

|

C1 – C2 |

0 |

0% |

The convenience sampling is defined as a sampling method that allows researchers to select appropriate participants who are willing, volunteer, or easily recruited to include in a sample [11, 13].

A sample consists of forty Russian non-linguistic students, who are studying at the Institute of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, South Ural State University (National Research University), Chelyabinsk, Russia. The participants enter at an B1 level and they are expected to leave the class at an B2 proficiency level, corresponding to the Common European Framework Reference for languages (CEFR). The participants’ information background is presented in Table 1.

Ethical approval was obtained to enroll these participants in the present study. All participants consent to participate in the research project by signing a form indicating their agreement.

Results and discussion

Along with the pedagogic intervention, questionnaires and online individual interviews were deployed to collect data for the present study. A period time of five weeks was for the data collection, which consists of one week for designing learning materials and activities, three weeks for the pedagogic intervention, one week for investigating the students’ perceptions, and transcript analysis.

The questionnaires were conducted online (using Google Forms) to investigate: (I) the students’ information backgrounds; (II) The Russian non-linguistic students’ perceptions of the insideclassroom learning activities in the Englishspeaking lessons; (III) The Russian non-linguistic students’ perceptions on the positive effect of PBLL in teaching speaking English, (IV) The Russian non-linguistic students’ perceptions on the negative effect of PBLL in teaching speaking English; and further comments on effects of PBLL or possible solutions in two open-ended questions. In addition, there were five objective question items in each section (II–IV), using the five-point Likert scale and featuring the following choices: (1) Strongly Disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Uncertain, (4) Agree, and (5) Strongly Agree. In order to enable the students to answer question items more accurately in their native language thinking mode and improve the reliability of the data, the questionnaires are designed in both English and Russian. Finally, a total of thirty-eight respondents gave their answers to the questionnaires.

We conducted individual interviews of 50 minutes in length to have the students’ detailed information about how they responded to the questionnaire (e. g., opinions, interests, or beliefs) and their further explanations for the performances or errors in their projects. A total of ten students were interviewed. All of the individual interviews were implemented in English. The interviewees’ responses were recorded. During the individual interviews, we noted the interviewees’ emerged ideas or thoughts for both referred purposes and data collection.

For the data collected from questionnaires, we deployed a frequency distribution (descriptive statistics), in which data values were systematically rank-ordered and the frequencies are provided for each of these values [11]. To illustrate this, the investigated variables in the questionnaires (section II–IV) were labeled in items and numbered from 6 to 20, and the percentages of the students, who responded to the questionnaire items with the five-point Likert scales, were provided for referred purposes. To make the data analysis more convenient, we divided the five-point Likert scales into “ Agree (Strongly Agree & Agree); Uncertainty ; and Disagree (Strongly Disagree & Disagree)”. For the data collected from the individual interviews, the researchers firstly transferred the audio scripts to textual data. Subsequently, the researchers categorized the textual data into specific headings or subheadings according to the investigated variables (i. e., the Russian non-linguistic students’ perceptions on the effectiveness of PBLL for English-speaking lessons, or the Russian non-linguistic students’ perceptions on the problems of PBLL for English-speaking lessons, or the improvements of students in speaking English through PBLL) (Table 2).

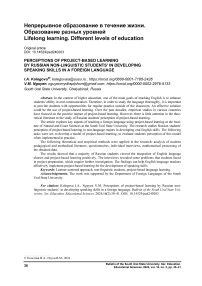

The students provided a positive evaluation of the inside-classroom activities for teaching English speaking skills in the present study. As shown in Fig. 1, nearly 80% of the students (30/38) were interested in learning activities in the English-speaking lessons.

Table 2

The samples of coding process

100.00%

90.00%

0.00%

80.00%

70.00%

60.00%

50.00%

40.00%

30.00%

20.00%

10.00%

I more practiced speaking English when working in small groups or pairs

I could use English as much as possible in the Englishspeaking lessons

I was interested in the learning activities in the Englishspeaking lessons

I felt confident in speaking English when participating in the English-speaking lessons

Disagree Uncertainty

Agree

5.26%

5.26%

15.79%

0%

28.95%

65.79%

7.89%

86.84%

31.58%

52.63%

21.05%

78.94%

Fig. 1. The percentage of students reflecting their perceptions of the inside-classroom learning activities for teaching English-speaking skills

Arguably, learning activities related to pairs or group work frequently enhance the students’ motivations and interests. Furthermore, these activities could foster students’ talking time through practices of speaking English with their partners or teammates. In this study, about 53% of the students (20/38) responded with the same ideas. At the same time, a major percentage of the students (86.84%) argued that they could use English as much as possible in the English-speaking lessons. Additionally, approximately 66% of the students (25/38) were to the point that they felt confident in speaking English when participating in the English-speaking lessons.

The positive effects of project-based language learning in English-speaking lesson

Generally, the Russian non-linguistic students had positive perceptions of PBLL for Englishspeaking lessons (Table 3). As can be seen in Table 3, about 63% of the students (24/38) agreed that the project-based language learning activities were useful for English-speaking lessons. Accordingly, they had more opportunities to practice speaking English regularly when participating in the project-based language learning activities, approximately 50% of the students (18/38) presented the agreements with this perception. In addition, 52.63% of the students (20/38) responded that they had generally improved English- speaking skills. This finding was consistent with that of Bakar [1]. After completing their projects, stu- dents presented their ideas and products in front of the class. Relating to this activity, there were about 42% of the students, who thought that they had felt more confident to make the presentation in English in front of the class. This finding aligns with the teacher’s perception in a study conducted by Slabodar [31] where the students are believed to improve their ability to make presentations in English in front of the audiences through PBLL. More interestingly, over 65% of the students (16/38) could learn something new in English from other students when participating in the project-based language learning activities.

Extract #1

Table 3

Frequency distribution of student positive perceptions of PBLL for English-speaking lessons

|

Items |

Statements |

Disagree |

Uncertainty |

Agree |

|

11 |

I found the PBLL activities useful for English-speaking lessons |

18.42% |

18.42% |

63.16% |

|

12 |

I had more opportunities to practice English regularly when participating in the PBLL activities |

15.79% |

36.84% |

47.37% |

|

13 |

I generally improved my English-speaking skills after participating in the PBLL activities |

13.16% |

34.21% |

52.63% |

|

14 |

I could learn something new in English from other students when participating in the PBLL activities |

10.53% |

23.68% |

65.78% |

|

15 |

I felt more confident when making the presentation in English in front of the class |

13.16% |

44.74% |

42.11% |

Extract #2:

Interviewee 1: It is difficult to gather group members to do projects […].

Interview 3: One of the difficulties is that there are many different assignments to do at the same time […].

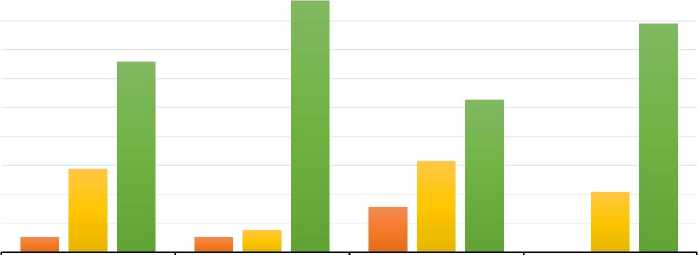

The proposed model for teaching

English-speaking skills through project-based language learning

Following the aforementioned discussion, we suggest a model for teaching English-speaking skills through PBLL (Fig. 2). In the classroom,

Table 4

Frequency distribution of student negative perceptions of PBLL for English-speaking lessons

Fig. 2. The model for teaching English-speaking skills through PBLL

learner-centered activities (e.g., roleplays, making conversations and discussion in groups or pairs) should be appropriately implemented to motivate students and prompt the use of English in the class [18, 25].

Conclusion

By integrating the pedagogic intervention into mixed-methods procedures, the present study was to investigate the Russian non-linguistic students’ perceptions of PBLL for teaching Englishspeaking skills. The findings revealed that the students positively viewed the effectiveness of PBLL in English-speaking

It is possible to state that PBLL is useful for teaching English, especially in the EFL context.

The present study has several pedagogical implications. First of all, PBLL should be effectively implemented in teaching speaking English as a foreign language to engage students in the meaningful use of English beyond the class. In addition, the teacher should apply learning projects that intersect with the students’ expectations and interests. To avoid problems in carrying out projects, students should be encouraged to regularly study in small groups (cooperative learning) and they might choose suitable team mates to complete the learning project effectively. As proposed by Myers [24], students who self-select their teammates perform higher levels of relational satisfaction than students who are randomly assigned to classroom work groups. Besides, students with higher levels of English might support lower ones through cooperative learning in small groups. More importantly, it is necessary to make a reasonable schedule for project time, depending on the particular mainstream educational curriculum. This helps students to have enough time to effectively complete their projects.

Список литературы Perceptions of project-based learning by Russian non-linguistic students’ in developing speaking skills in a foreign language

- Bakar N.I.A., Noordin N., Razali A.B. Improving Oral Communicative Competence in English Using Project-Based Learning Activities. English Language Teaching, 2009, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 73-84. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v12n4p73 (accessed 17.09.2023).

- Beckett G.H. Project-Based Second and Foreign Language Education: Theory, Research and Practice. Ed. by G.H. Beckett, P.C. Miller. Project-Based Second and Foreign Language Education: Past, Present and Future, Information Age, 2006, pp. 3-18.

- Beckett G.H., Slater T. The Project Framework: a Tool for Language, Content and Skills Integration. ELT Journal, 2005, vol. 59, no. 2, pp.108-116. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/eltj/cci024 (accessed 10.10.2023).

- Beckett G. Teacher and Student Evaluations of Project-Based Instruction. TESL Canada Journal, 2002, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 52-66. Available at: https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v19i2.929 (accessed 07.12.2023).

- Bell S. Project-Based Learning for the 21st Century: Skills for the Future. The Clearing House, 2010, vol. 83, no. 2, pp. 39-43. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00098650903505415 (accessed 15.11.2023).

- Bleistein T., Smith M.K., Lewis M. Teaching speaking (Revised Edition). Virginia, USA, Tesol Press Publ., 2020. 90 p.

- Boudersa N., Hamada H. Student-Centered Teaching Practices: Focus on The Project-Based Model to Teaching in the Algerian High-School Contexts. Arab World English Journal, 2015, pp.25-41.

- Boynton P.M., Greenhalgh T. Selecting, Designing, and Developing your questionnaire. BMJ, 2004, vol. 328, no. 7451, pp. 1312-1315. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7451.1312 (accessed 08.11.2023).

- Brown J.D., Hudson T. The Alternatives in Language Assessment. TESOL Quarterly, 1998, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 653-675. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/3587999 (accessed 02.06.2023).

- Burns A. A Holistic Approach to Teaching Speaking in the Language Classroom. Stockholm University, 2012. Available at: https://www.andrasprak.su.se/polopoly_fs/L204517.1411636356l/menu/ standard/file/Anne_Burns.pdf.

- Christensen L.B., Johnson R.B., Turner L.A. Research Methods, Design, and Analysis (13th Ed.). Hoboken, USA: Pearson Press Publ., 2020. 539 p.

- Chappell P. Group Work in the English Language Curriculum: Sociocultural and Ecological Perspectives on Second Language Classroom Learning. Basingstoke, England, Palgrave Macmillan Publ., 2014. 212 p.

- Cresswell J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (3rd Ed.). London, United Kingdom, SAGE publications, Inc. Publ., 2009. 438 p.

- Dornyei Z., Taguchi T. Questionnaires in Second Language Research Construction, Administration, and Processing (2nd Ed.). New York, USA: Taylor & Francis Press, 2010. 185 p.

- Garib A. "Actually, it's real work": EFL Teachers' Perceptions of Technology-Assisted Project-Based Language Learning in Lebanon, Libya, and Syria. TESOL Quarterly, 2022, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 1-29. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3202 (accessed 19.12.2023).

- Huerta-Macías A. Alternative Assessment: Responses to Commonly Asked Questions. Ed. by Richards J., Renandya W. Methodology in Language Teaching: an Anthology of Current Practice. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press Publ., 2002, pp. 338-343.

- Hendrickson J.M. Error Correction in Foreign Language Teaching: Recent Theory, Research and Practice. The Modern Language Journal, 1978, vol. 62, no. 8, pp. 387-398. Available at: https:// elanoldenburg.files.wordpress.com/2008/11/hendricksonerrorcorrection2.pdf (accessed 10.01.2024)

- Jambor Z.P. Learner Attitudes Toward Learner Centered Education and English as a Foreign Language in the Korean University Classroom. Unpublished. Diss. Master (Arts). Birmingham, the University of Birmingham, 2007. 78 p. Available at: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/documents/collegeartslaw/ cels/essays/matefltesldissertations/jambordissertation.pdf (accessed 15.01.2024).

- Juárez G.H., Herrera L.M.M. Learning Gain Study in a Strategy of Flipped Learning in the Undergraduate Level. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), 2009, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 1245-1258. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12008-019-00594-3 (accessed 23.10.2023).

- Kolegova I.A., Levina I.A. Module and Project-Based Teaching of Foreign Language to Future Economists. Bulletin of the South Ural State University. Ser. Education. Educational Sciences, 2022, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 6-13. Available at: https://doi.org/10.14529/ped220401 (accessed 25.01.2024).

- Kotlyarova I.O. The Phenomenon of Integration in the Theory and Practice of Education. Bulletin of the South Ural State University. Ser. Education. Educational Sciences, 2023, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 5-17. (In Russ.) Available at: https://doi.org/10.14529/ped230301 (accessed 20.01.2024).

- Kovalyova Y.Y., Soboleva A.V., Kerimkulov A. Project-Based Learning in Teaching Communication Skills in English as a Foreign Language to Engineering Students. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 2016, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 153-156. Available at: https:// doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v11i04.5416 (accessed 29.01.2024).

- Littlewood W., Wang S. Exploring Students' Demotivation and Remotivation in Learning English. System, 2021, vol. 103, no. 1, pp. 1-10. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102617 (accessed 25.12.2023).

- Myers S.A. Students' Perceptions of Classroom Group Work as a Function of Group Member Selection. Communication Teacher, 2012, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 50-64. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/ 17404622.2011.625368 (accessed 20.12.2023).

- Nunan D. Second Language Teaching & Learning. Boston, MA, Heinle & Heinle publishers Publ., 1999. 330 p.

- Nguyen V.M. English Language-Learning Environments in COVID-19 Era: EFL Contexts, English-Language Environments, Technology-Based Aapproach, English Language Learning. AsiaCALL Online Journal, 2021, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 39-46. Available at: https://asiacall.info/acoj/index.php/ journal/article/view/21 (accessed 04.12.2023).

- Nguyen V.M. Positive Effects of Video-Based Projects on the Communicative English Grammar Lessons. International Journal of Language and Literary Studies, 2021, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 54-68. Available at: https://doi.org/10.36892/ijlls.v2i3.666 (accessed 10.12.2023)

- Nguyen V.M. Solutions to Problems of the Communicative Language Teaching Activities: Raising Learners' Motivations and Applying Technology Equipment. Proceeding of the International Conference "Language Teaching and Learning Today". Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh Press Publ., 2019, pp. 164 -181.

- Poonpon K. Enhancing English Skills through Project-Based Learning. The English Teacher, 2017, vol. 10 (L), pp.1-10.

- Richards J.C. The Changing Face of Language Learning: Learning Beyond the Classroom. RELC Journal, 2015, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 5-22. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688214561621 (accessed 05.12.2023).

- Slabodar I. What do the Lecturers Think? EPIC Lecturers' Perceptions of Implementing PBLL to Teach the Speaking Skills. Teaching English as a Second Language Electronic Journal (TESL-EJ), 2023, vol. 27, no. 2. Available at: https://doi.org/10.55593/ej.27106a4 (accessed 14.01.2024).

- Yamada H. An Implementation of Project-Based Learning in an EFL Context: Japanese Students' and Teachers' Perceptions Regarding Team Learning. TESOL Journal, 2020, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1-16. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.519 (accessed 12.01.2024).

- Zhang Y.Y. Project-Based Learning in Chinese College English Listening and Speaking Course: from Theory to Practice. Canadian Social Science, 2015, vol. 11, no. 9, pp. 40-44. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.3968/7532 (accessed 15.01.2024).