Research trends in media pedagogy: between the paradigm of risk and the paradigm of opportunity

Автор: Tomczyk Łukasz

Журнал: International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education @ijcrsee

Рубрика: Review articles

Статья в выпуске: 3 vol.9, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The use of computers, internet, and smartphones in the learning and teaching process has become an irreversible fact. Information and communication technologies (ICT) are now one of the fundamental teaching resources and even one of the principal teaching environments. The widespread use of ICT stands in positive correlation to the growing number of studies on educational aspects of the use of new media in schooling. The dynamically growing number of publications in this field requires reflection on the directions of research in the intensely developing sub-discipline of education science, i.e. media pedagogy. The aim of the article is to explore the two dominant directions of research on didactic and upbringing aspects of ICT use in education. The text presents the assumptions and processes assigned to both the opportunity paradigm and the risk paradigm of media pedagogy. These paradigms clash, giving rise to research directed at positive or negative phenomena related to the digitalization of schooling and educational processes. The text is an attempt to draw attention not only to the development of media pedagogy, but also to methodological errors resulting from anchoring research to only one trend.

Media education, paradigms, school, digitalization of education, risk paradigm, opportunity paradigm

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170198644

IDR: 170198644 | УДК: 37.091:004 | DOI: 10.23947/2334-8496-2021-9-3-399-406

Текст обзорной статьи Research trends in media pedagogy: between the paradigm of risk and the paradigm of opportunity

© 2021 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license .

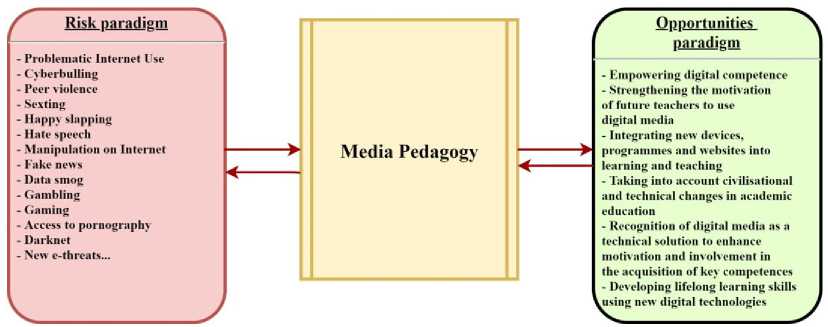

For this reason, it has become necessary to conduct analyses of the research results and redefine the perspective regarding the relationship between the paradigms in the context of modern challenges. There is an urgent need for the integration of the two paradigms due to the rapid changes in the information society and the apparent need to prepare modern teaching staff in the wider European community. A brief summary of the elements assigned to both paradigms is presented in Diagram 1.

Diagram 1. The risk paradigm and the opportunity paradigm

Source: own source

The aim of the article is to explore the characteristics of both the risk paradigm and the opportunity paradigm of media pedagogy. An intermediary aim of this article is to draw attention to the errors and methodological limitations arising from the narrowing of educational research to one perspective, i.e. positive or negative options, as they relate to the digitalization of schooling or educational processes.

Digitalization of education

The phenomenon of the digitalization of education is a global challenge. The process of the implementation of ICT in formal education means that this topic arouses interest not only in specialists involved in educational research in the fields of pedeutology, media pedagogy, educational theory, and computer science, but it also arouses the curiosity of the general public. The effective use of digital media by teaching staff and students has been particularly noticed in the period since March 2020, when most of the processes related to education and upbringing were involuntarily “digitized” ( Potyrała et al., 2021 ; Tomczyk and Walker, 2021 ).

The digitalization of education has become an irreversible phenomenon. For more than two decades, both teachers and experts (scientists, NGO representatives) have drawn attention to the fact that it is necessary to modernize educational environments through the use of IT devices, computers, smartphones, software, and websites that can all become effective teaching resources ( Stošić, 2015 ). Nowadays, i.e. in the post-pandemic stage, the use of new technologies in education has acquired a new meaning. ICTs have not only become an attractive educational gadget, but have formed the basis for crisis didactics (emergency e-learning) over the last several months, enabling the continuity of the educational process in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic ( Ptaszek et al., 2020 ).

Currently, there appears to be no turning back towards the non-application of ICT in education. The implementation of ICT in education in recent years has usually been carried out in an unaccelerated emergency manner. Teachers have become acquainted with the possibilities of new technologies within the framework of self-study, peer education, and specialised courses. In this way, they sought to raise the level of their own digital competences oriented towards teaching and educational activities (Novković Cvetkovićet, Stošić and Belousova, 2018). The digitalisation of education has also taken place through government programmes, the enhancement of teachers’ professional education, and the participation of schools in projects that seek to improve teachers’ teaching skills. In short, changes to the implementation of ICT in subject teaching were usually accelerated by external actors. Nevertheless, there were also situations when transformations took place from the inside, perhaps through passionate teachers or techno-optimistic principals who implemented e-learning platforms in their own schools in recent years, equipped their institutions with Wi-Fi, interactive whiteboards, laptops, tablets, 3D printers, robots, e-books, or software for simulating phenomena (Tomczyk et al. 2017). Regardless of whether the changes associated with the digitalization of education were triggered by external or internal circumstances, it was an inevitable but slow process. Digitalization occurred according to the capacity of the institutions funding education, was mediated by teachers’ attitudes towards new media, or was linked to the broader development of the information society (Ziemba, 2019; Walotek-Ściańska et al., 2014). Most recently, the process of digitalization has gained speed due to the aforementioned economic, pandemic, and modernisation processes.

The focus on digitalization was not only determined by the positive possibilities inherent in the use of ICT in subject teaching. For a long time both teachers and researchers have been focusing on the negative effects of new media on individuals and selected social groups in unusual, abnormal, or crisis situations. Typically, reflection or preventive actions related to the negative consequences of new media use have emerged in circumstances of situations such as cyberbullying ( Pyżalski, 2012 ; Del Rey et al., 2015 ), sexting ( Pyżalski et al., 2019 ), copyright infringement ( Tomczyk, 2019 ), and others. Crises resulting from the negative use of ICT forced schools to take swift action to curtail the phenomenon and counteract the negative consequences ( Tomczyk, 2017 ). The digitalization of education, therefore, generated a number of educational problems that were then faced by teachers, students, parents, and the school management.

Digitalization has caused a division of teachers into groups negatively oriented towards new technologies on the one hand and on the other, enthusiasts who see the potential of new media in education. The dual character of new media has also been noticed among experts involved in research on the processes of upbringing and education. A rarity in comprehensive studies is showing the process of digitalization of education through the simultaneous presentation of ‘dark’ and ‘light’ sides of ICT. Very often the subject of digitalization in scientific studies has been clearly oriented towards exclusively positive or negative dimensions. Of course, this condition has not applied to all studies (e.g. Global Kids Online, EU Kids Online); however, as a trend it has certainly been visible in media pedagogy. The orientation towards one dimension was not only due to the attitude of the researchers dealing with the issues surrounding digitalization, but was also a kind of mapping of the school reality.

In order to understand more fully the extreme approaches involved in the implementation of new media in the educational space, both research trends attributed to media pedagogy are discussed below.

Opportunity paradigm

Researchers, techno-enthusiasts, and teachers representing the research stream and the style of thinking assigned to the opportunity paradigm, emphasise in their statements, analyses, and theoretical frameworks the necessity of implementing teaching solutions based on ICT. Representatives of this perspective automatically assume the existence of positive consequences related to the implementation and use of ICT in school didactics and educational activities ( Greenstein, 2016 ; Tomczyk, 2017 ; Alexander and Rutherford, 2019 ; Tomczyk, 2021 ). Very often the analysis of the impact of new media is combined with technological progress and the necessity to modernise education. Research on the positive aspects of ICT in education stems from the perception of digital didactic means as solutions that are attractive to students, and that enable increased concentration, satisfaction, and involvement during learning. The aforementioned features of the opportunity paradigm are effectively used as an argument justifying the directions of development of formal and non-formal education with the use of digital hardware resources and the Internet ( Tomczyk, 2021 ).

Researchers conducting studies anchored only in the opportunities paradigm are propagators of the idea of the computerisation of education, and thus they clearly see the opportunities that result from the use of ICT. Representatives of this paradigm are convinced of the legitimacy of implementing and conducting research with an emphasis on the benefits of using IT devices (e.g. tablets, mobile phones, computers), and digital teaching aids (e.g. multimedia boards, digital printers, educational software), as well as virtual educational and communication environments (e.g. e-learning platforms). Sometimes researchers assigned to this stream do not take into account the dual character of new media. One consequence of this situation is the creation of research tools, as well as theoretical frameworks, which are prepared only to confirm the only valid hypothesis, which is that without ICT, the quality of education decreases. Such an erroneous assumption may result from poor knowledge of the impact of the use of new media in education, or a high level of techno-optimism, or from insufficient experience either in designing research that takes into account the broader context of media pedagogy or in the broader realm of pedagogical research methodology. At the same time, it should be emphasised that not all of the research anchored in the opportunity paradigm of media pedagogy leads to erroneous results. However, highlighting only the positive sides of the use of new technologies is fraught with the risk of various kinds of errors related to the interpretation of the complex ecosystem that is educational reality.

In order to more precisely exemplify the opportunity paradigm, it is worth referring to the most common phenomena and processes attributed to the positive impact of new media on learning, teaching, and education. For this purpose, it will be useful to use the EU KIDS Online typology, which notes that ICTs in educational contexts are useful as educational resources, enabling contact with others to develop one’s own interests, providing an opportunity to create, initiate, and collaborate in the learning process, enabling access to global information including OER, are useful in creating diverse forms of social engagement, are the basis for creating educational content, are a transmitter of guidance activities, and provide an opportunity for a multifaceted understanding of the surrounding reality, as well as the opportunity to express one’s own identity ( Livingstone and Haddon, 2009 ; Haddon and Livingstone, 2017 ). In turn, Jacek Pyżalski in analysing the phenomena assigned to the paradigm of opportunities in media pedagogy points out that the Internet has become the basis for many positive developmental phenomena for children and young people. Analysing the positive aspects of the impact of new media, he further notes their importance in education and self-development, and in the development of competence in specialised, self-creative, social, consistent, independent, original ways, leading to protection against unwarranted criticism, as well as increased patience, self-improvement, and independence ( Pyżalski, 2019 ). ICT can therefore be a crucial factor in self-development, as well as in improving hard competences of use in the labour market. The opportunity paradigm offers a wide spectrum of possibilities, many of which are proffered by cyberspace and digital tools.

Analysing the last few years of research in the area of media pedagogy, it is possible to see that the positive possibilities of ICT are also linked to creating efficient digital learning environments ( Sanchez, et al, 2021 ; Chan, Bogdanovic and Kalivarapu, 2021 ), supporting the development of children and young people with special educational needs ( Gallardo-Montes et al., 2021 ), simulating real world phenomena through VR and AR technologies ( Fedeli, 2013 ; Gaol and Prasolova-Førland, 2021 ), supporting the development of teamwork skills ( Awour et al, 2021 ), enhancing the functioning of vocational education ( Cattaneo, Antonietti and Rauseo, 2022 ), strengthening the assessment of educational outcomes ( Misiejuk and Wasson, 2021 ), diversifying learning methods and self-assessment ( Cheng, Bogdanovic and Kalivarapu, 2021 ), supporting the development of soft skills ( Samuelsson, Price and Jewitt, 2021 ), and predicting educational achievements ( Yu, Wu and Liu, 2019 ). The aforementioned aspects of the application of ICT are only a fraction of the possibilities offered by ICT. Nowadays, cyberspace and digital devices lend themselves to unlimited deployment in almost every area related to learning and teaching. In turn, such implementations offer an opportunity for pedagogical measurement, which can be based on the opportunity paradigm of media pedagogy, thus significantly highlighting the advantages of using ICT in the educational dimension. The focus of researchers and educators on positive aspects is a driving force for change. The assumption of working hypotheses when implementing new ICT solutions in didactics and education is an indispensable activity for the opportunity paradigm of media pedagogy. The paradigm provides opportunities to improve the educational system through taking into account the strengths that result from the specificities of new media: multimedia, versatility, speed of operation, speed of data transfer, and the universality of ICT, not to mention the exponential growth of software aimed at education. The opportunity paradigm is therefore the basis for many studies on the educational application of ICT for both formal, informal, and non-formal education.

Risk paradigm

A different perspective of the phenomenon of digitisation is provided by research embedded in the risk paradigm. Research that represents the risk paradigm is characterised by an emphasis of the negative consequences that result from the pervasiveness of ICT. In this view, ICT are the cause or consequence of negative behaviors. The use of new media may lead to the breaking of the rules of social life, and can contribute to physical and mental health problems that lead to long-term disorders. Experts embedded in this paradigm very often link negative phenomena mediated by digital media to each other, and integrate problematic functioning in the online world with similar problems in the offline world. The risk paradigm is a kind of warning about how digital technologies hijack life and impede proper socialisation and upbringing (Tusseyev et al., 2021). Studies and opinions representing the risk paradigm are very often cited when problematic behavior among children and adolescents emerges and it is new technologies that receive the blame. Phenomena assigned to the risk paradigm are also often an argument in discussions on the psychosocial functioning of children and adolescents in the modern world. The range of phenomena associated with the ‘dark side’ of the Internet is systematically expanding with the development of information society services.

In the aforementioned EU Kids Online model, the authors highlight that the Internet can be both a space and a source for fostering undesirable behavior ( Pyżalski et al., 2019 ). However, in many reports on negative behavior, cyberspace is just an additional place where young people with certain tendencies are exposed to undesirable phenomena ( Tomczyk and Wąsiński, 2020 ). Thus, in the risk paradigm, one can encounter multiple approaches where new technologies are the cause, the effect, and the space of e-risks.

Typical phenomena attributed to the risk paradigm of media pedagogy include electronic violence and aggression, harassment and stalking, access to pornography, grooming and abuse of sexual content, exposure to encounters with strangers, distress by providing inappropriate content, sexting, exposure to racist content, hate speech, and ideological manipulation. Among the phenomena of concern, representatives of EU KIDS Online also mention the generation of potentially harmful content, product placement, misuse of personal data, access to gambling, and copyright infringement ( Livingstone, Mascheroni and Staksrud, 2017 ). Other threats in the digital world include the issue of problematic internet use (often mistakenly defined as internet addiction) ( Király et al., 2014 ; Király and Demetrovics, 2021 ), and pathostreaming ( Kmieciak-Goławska, 2018 ), FOMO ( Jupowicz-Ginalska, 2018 ), and nomophobia ( Bhattacharya et al., 2019 ).

Jacek Pyżalski, in assessing the behaviors assigned to the risk paradigm of media pedagogy, clearly stresses that the activities listed above are undertaken by a minority, whereas in analysing the literature on the subject, one may receive the impression that they concern the entire adolescent population. Presenting young users of new media only as perpetrators and victims of incidents assigned to the risk paradigm of media pedagogy may create a distorted image of this age group. Pyżalski also points out that the dark side of the Internet is researched through small samples (often accidental), using non-standardised research tools without a proper theoretical foundation, or by overinterpreting the data collected ( Pyżalski, 2017 ). The position he presents is very important for several reasons. Firstly, when examining risky phenomena, it should be kept in mind that only a small percentage of young users of new media experience e-risks, and an even smaller percentage trigger such threats. Moreover, young people are not always fully prepared to deal with problems related to cyberspace on their own. Despite the fact that this is a group which uses new media intensively, selected layers of competence within this group need to be strengthened. The stereotypical approach to young people, indicated by Pyżalski, as intensive users of ICT and also the most threatened or most likely to pose a threat, is surely the wrong approach. The risk paradigm is very often used by educators to show the dark side of new media, as well as to highlight the problems that the young generation of users causes. However, in most cases the studies of this type do not fulfill the elementary principles of social research methodology in the field of pedagogical sciences.

Methodological errors and paradigms of research in media pedagogy – the author’s approach

The two positions presented here are the basis for many studies attributed to media pedagogy and psychology. The unambiguous focus on the positive or negative aspects of the influence of new media on processes related to education is visible in the research assumptions (objectives, hypotheses, ways of interpreting research results) or is unintentionally hidden through how the narrative is constructed around the features and directions of influence of ICT. Emphasising too strongly the positive or negative aspects, or failing to take into account phenomena from the opposite side in the creation of the research model, may lead to errors. This list is an attempt to point out the most typical errors resulting from the failure to take into account the duality of the paradigms. Ten typical errors that may result from intentional or unintentional consideration of only one research paradigm are described below.

-

1. Creating stereotypical knowledge about the influence of the media on the upbringing and educational processes.

-

2. Strengthening negative beliefs among parents, teachers, and students about the use of ICT in education and upbringing.

-

3. Increasing information noise about the impact of ICT on the behavior of individuals and groups.

-

4. Making public methodologically flawed research reports that may become an unscientific basis for the creation and implementation of school digitalization policies.

-

5. Generating descriptions of educational phenomena lacking a holistic perspective.

-

6. Creating false beliefs and establishing incorrect norms related to the how new media is used by children and young people, with these beliefs then providing the basis for the production of new, inadequate, diagnostic tools.

-

7. Methodologically flawed publications entering the scientific circuit, which are then disseminated and cited by less experienced researchers.

-

8. Conducting research that has no real application in the school reality, and therefore is inherently useless.

-

9. Creating training programmes (e.g. preparing future pedagogical staff, or teachers improving their own competences) based on one type of dominant narrative, either techno-optimism or technopessimism.

-

10. Lowering the prestige of media pedagogy as a science based on unclearly defined paradigms or popular opinions.

The errors presented above are typical situations that may occur when one of the two paradigms is dominant or absent. Of course, it should also be taken into account that more experienced scientists or teachers, as well as people with a high level of critical thinking, are able to spot such errors and inaccuracies. Nevertheless, the 10 most common consequences represent a set of specific arguments about the need for a serious and critical debate on the quality of research attributed to media pedagogy.

Conclusions

In analysing the results of research on young people’s behavior in cyberspace, two dichotomous approaches can be observed among teachers, parents, researchers, opinion leaders, and institutions. One of these assumes that digital media bring a number of positive effects when they are integrated into the processes of learning, teaching, and leisure. It is the representatives of this point of view who appreciate the role of ICT, who link the use of digital media with positive effects from a pedagogical point of view. Sometimes these opinions and actions are exaggerated, lacking an empirical basis. One of the most frequently mentioned arguments for including ICT (sometimes thoughtlessly) in almost every educational activity is the desire to keep up with technological progress. The use of newer and faster digital devices as well as graphically appealing software and websites seems to be an indicator of keeping up with constant and rapid change. The opportunity paradigm in scientific and colloquial discussion repeatedly ‘clashes’ with the opposite perspective, where the emphasis is on the negative consequences of ICT use. The risk paradigm is particularly evident in the global studies of media psychologists, where it is assumed that the Internet may be a source or a space conducive to aggression and peer violence, access to pornographic materials, and the sexual and other negative behaviors discussed in the present study. Each of these risks raises many concerns and controversies from an educational perspective. Moreover, each issue is characterised by a huge number of scientific publications (empirical studies) and methodological studies (how to effectively counter e-risks and implement digital media in the process of education and upbringing). However, many of these studies, and thus research, have a unidirectional tone that does not take into account the opposite perspective. Therefore, it becomes necessary to conduct meta-analyses of research results and redefine our perspective on the relationship between the two paradigms in the context of contemporary challenges, with this having a knock-on effect on the modernization of programs that prepare pedagogical personnel.

The risk paradigm and the opportunity paradigm are two increasingly visible trends and research directions in media pedagogy. It is rare for both perspectives to be combined in studies devoted to the education or psychosocial functioning of children and adolescents in the new media space. As shown in this study, each of these paradigms emphasises one side of the impact of new media on groups and individuals. Conducting research in either one or the other runs the risk of distorting reality, which may not only lead to a deepening of the disagreement between techno-optimists and techno-pessimists ( Tomczyk, 2017 ), but also build new stereotypes, distort the basis for creating effective directions for the digitalization of education, and create an imprecise theoretical framework for effective preventive actions against e-risks.

Both the risk paradigm and the opportunity paradigm are necessary directions for reflection on the changes that new media bring about in upbringing and education. The interpenetration of different opinions, positions, assumptions, research results, and theories on the opportunities inherent in new media (Stošić, 2015; Tomczyk and Kopecký, 2016) is a necessity in realizing methodologically correct research on the digitalization of education. The lack of simultaneous consideration of both perspectives in further research assigned to media pedagogy may become one of the cardinal mistakes in the next stage of the development of media pedagogy.

Acknowledgements

The article was written as part of the project “Teachers of the future in the information society— between risk and opportunity paradigm” funded by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange under the Bekker programme, Grant number: PPN/BEK/2020/1/00176. The author would like to thank Prof. Laura Fedeli from the University of Macerata, Italy, for her support with the implementation of the research grant.

Conflict of interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Список литературы Research trends in media pedagogy: between the paradigm of risk and the paradigm of opportunity

- Alexander, S., & Rutherford, J. (2019). A critique of techno-optimism. Routledge handbook of global sustainability governance, 152-167.

- Awuor, N. O., Weng, C., Piedad, E., & Militar, R. (2021). Teamwork competency and satisfaction in online group project-based engineering course: The cross-level moderating effect of collective efficacy and flipped instruction. Computers & Education, 104357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104357

- Bhattacharya, S., Bashar, M. A., Srivastava, A., & Singh, A. (2019). Nomophobia: No mobile phone phobia. Journal of family medicine and primary care, 8(4), 1297. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_71_19

- Cattaneo, A. A., Antonietti, C., & Rauseo, M. (2022). How digitalised are vocational teachers? Assessing digital competence in vocational education and looking at its underlying factors. Computers & Education, 176, 104358. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104358

- Chan, C.-S., Bogdanovic, J., & Kalivarapu, V. (2021). Applying immersive virtual reality for remote teaching architectural history. Education and Information Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10786-8

- Chang, C. Y., Hwang, G. J., & Gau, M. L. (2021). Promoting students’ learning achievement and self-efficacy: A mobile chatbot approach for nursing training. British Journal of Educational Technology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13158

- Del Rey, R., Casas, J. A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Smith, P., ... & Plichta, P. (2015). Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 141-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.065

- Fedeli, L. (2013). Embodiment e mondi virtuali. Implicazioni didattiche [Embodiment and virtual worlds. Didactic implications]. Milano: Franco Angeli.

- Gallardo-Montes, C. del P., Caurcel Cara, M. J., & Rodríguez Fuentes, A. (2021). Technologies in the education of children and teenagers with autism: evaluation and classification of apps by work areas. Education and Information Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10773-z

- Gaol, F.L., Prasolova-Førland, E. (2021) Special section editorial: The frontiers of augmented and mixed reality in all levels of education. Education and Information Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10746-2

- Greenstein, S. (2016). Ten Open Questions for Techno-Optimists. IEEE Micro, 36(04), 86-87. https://doi.org/10.1109/ MM.2016.65

- Haddon, L., & Livingstone, S. (2017). Risks, Opportunities, and Risky Opportunities: How Children Make Sense of the Online Environment. Cognitive Development. Digital Contexts, 275–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-809481-5.00014- 6

- Jupowicz-Ginalska, A., Jasiewicz, J., Kisilowska, M., Baran, T., & Wysocki, A. (2018). FOMO. Polacy a lęk przed odłączeniem– raport z badań [FOMO. Poles and the Fear of Missing Out–A Research Report]. Warszawa: Wydział Dziennikarstwa Informacji i Bibliologii UW.

- Keane, T., Keane, W. F., & Blicblau, A. S. (2016). Beyond traditional literacy: Learning and transformative practices using ICT. Education and Information Technologies, 21(4), 769-781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-014-9353-5

- Király, O., & Demetrovics, Z. (2021). Problematic Internet Use. In Textbook of Addiction Treatment (pp. 955-965). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36391-8_67

- Király, O., Griffiths, M. D., Urbán, R., Farkas, J., Kökönyei, G., Elekes, Z., ... & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Problematic Internet use and problematic online gaming are not the same: Findings from a large nationally representative adolescent sample. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(12), 749-754. https://doi.org/ 10.1089/cyber.2014.0475

- Kmieciak-Goławska, A. (2018). Patostreaming jako narzędzie popularyzacji podkultury przemocy [Pathostreaming as a tool for popularizing the subculture of violence]. Biuletyn Polskiego Towarzystwa Kryminologicznego im. prof. Stanisława Batawii, (25), 171-183.

- Livingstone, S. (2004). Media Literacy and the Challenge of New Information and Communication Technologies. The Communication Review, 7(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714420490280152

- Livingstone, S., & Haddon, L. (2009). EU Kids Online. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology, 217(4), 236. Retrieved from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/24372

- Livingstone, S., Mascheroni, G., & Staksrud, E. (2017). European research on children’s internet use: Assessing the past and anticipating the future. New Media & Society, 20(3), 1103–1122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816685930

- Misiejuk, K., & Wasson, B. (2021). Backward evaluation in peer assessment: A scoping review. Computers & Education, 104319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104319

- Novković Cvetković, B., Stošić, L., & Belousova, A. (2018). Media and information literacy-the basis for applying digital technolo-gies in teaching from the discourse of educational needs of teachers. Croatian Journal of Education: Hrvatski časopis za odgoj i obrazovanje, 20(4), 1089-1114. https://doi.org/ 10.15516/cje.v20i4.3001

- Pelgrum, W. (2001). Obstacles to the integration of ICT in education: results from a worldwide educational assessment. Computers & Education, 37(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0360-1315(01)00045-8

- Petko, D. (2012). Teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and their use of digital media in classrooms: Sharpening the focus of the ‘will, skill, tool’ model and integrating teachers’ constructivist orientations. Computers & Education, 58(4), 1351-1359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.12.013

- Potyrała, K., Demeshkant, N., Czerwiec, K., Jancarz-Łanczkowska, B., & Tomczyk, Ł. (2021). Head teachers’ opinions on the future of school education conditioned by emergency remote teaching. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 7451–7475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10600-5

- Ptaszek, G., Stunża, G. D., Pyżalski, J., Dębski, M., & Bigaj, M. (2020). Edukacja zdalna: co stało się z uczniami, ich rodzicami i nauczycielami [Remote education: what happened to students, their parents and teachers]. Gdańsk: Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne Sp. z oo.

- Pyżalski J. (2019). Internet i jego młodzi twórcy – dobre i złe wiadomości z badań jakościowych [The Internet and its young cre-ators - good and bad news from qualitative research]. Warszawa: NASK.

- Pyżalski, J. (2012). From cyberbullying to electronic aggression: Typology of the phenomenon. Emotional and behavioral difficulties, 17(3-4), 305-317. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2012.704319

- Pyżalski, J. (2017). Jasna strona-partycypacja i zaangażowanie dzieci i młodzieży w korzystne rozwojowo i prospołeczne działania [The bright side - participation and involvement of children and youth in developmentally and pro-social activi-ties]. Dziecko krzywdzone. Teoria, badania, praktyka, 16(1), 288-303. Retrieved from https://dzieckokrzywdzone.fdds. pl/index.php/DK/article/view/587

- Pyżalski, J., Zdrodowska, A., Tomczyk, Ł., & Abramczuk, K. (2019). Polskie badanie EU Kids Online 2018 [Polish EU Kids Online 2018 survey]. Najważniejsze wyniki i wnioski. Poznań: UAM. Retrieved from https://depot.ceon.pl/ handle/123456789/17037

- Reyes, V. C., Reading, C., Doyle, H., & Gregory, S. (2017). Integrating ICT into teacher education programs from a TPACK perspective: Exploring perceptions of university lecturers. Computers & Education, 115, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. compedu.2017.07.009

- Samuelsson, R., Price, S., & Jewitt, C. (2021). How pedagogical relations in early years settings are reconfigured by interactive touchscreens. British Journal of Educational Technology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13152

- Sanchez, E., Paukovics, E., Cheniti-Belcadhi, L., El Khayat, G., Said, B., & Korbaa, O. (2021). What do you mean by learning lab? Education and Information Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10783-x

- Smahel, D., Machackova, H., Mascheroni, G., Dedkova, L., Staksrud, E., Ólafsson, K., Livingstone, S.,& Hasebrink, U. (2020). EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries. EU Kids Online. https://doi.org/10.21953/lse.47fdeqj01ofo

- Stošić, L. (2015). The importance of educational technology in teaching. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education (IJCRSEE), 3(1), 111–114. https://doi.org/10.23947/2334-8496-2015-3-1-111-114

- Tomczyk, Ł. (2017). Nowe media a zagrożenia i działania profilaktyczne na przykładzie założeń programu Bezpieczna+[ New media versus threats and preventive measures on the example of the assumptions of the Safe program]. In M. Górka (ed). Cyberbezpieczeństwo dzieci i młodzieży. Realny i wirtualny problem polityki bezpieczeństwa. Warszawa: Wydaw. Difin.

- Tomczyk, Ł. (2019). The Practice of Downloading copyrighted files among adolescents in Poland: Correlations between piracy and other risky and protective behaviors online and offline. Technology in Society, 58, 101137. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j. techsoc.2019.05.001

- Tomczyk, Ł. (2021). Skala i mechanizmy piractwa cyfrowego wśród czeskich i polskich adolescentów w perspektywie paradygmatu ryzyka pedagogiki mediów [The scale and mechanisms of digital piracy among Czech and Polish adoles-cents in the perspective of the risk paradigm of media pedagogy]. Kraków: Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny. https://doi. org/10.24917/9788380847231

- Tomczyk, Ł., & Kopecký, K. (2016). Children and youth safety on the Internet: Experiences from Czech Republic and Poland. Telematics and Informatics, 33(3), 822-833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.12.003

- Tomczyk, Ł., & Walker, C. (2021). The emergency (crisis) e-learning as a challenge for teachers in Poland. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 6847–6877. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10539-7

- Tomczyk, Ł., & Wąsiński, A. (2020). Risk Behaviors among Youths in a Two-Aspect Approach: Using Psychoactive Substances and Problematic Using of Internet. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 29(1), 27-45. https://doi.org/10.10 80/1067828X.2020.1805839

- Tomczyk, Ł., Szotkowski, R., Fabiś, A., Wąsiński, A., Chudý, Š., & Neumeister, P. (2017). Selected aspects of conditions in the use of new media as an important part of the training of teachers in the Czech Republic and Poland-differences, risks and threats. Education and Information Technologies, 22(3), 747-767. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10639-015-9455-8

- Tusseyev, M., Torybayeva, J., Ibragim, K., Gurbanova, A., & Nazarova, G. (2021). Ensuring the safety of learning and teaching environments. World Journal on Educational Technology: Current Issues, 13(4), 1029–1039. https://doi.org/10.18844/ wjet.v13i4.6299

- Walotek-Ściańska, K., Szyszka, M., Wąsiński, A., & Smołucha, D. (2014). New media in the social spaces. Strategies of influence. Verbum: Prague. Retrieved from https://depot.ceon.pl/bitstream/handle/123456789/7281/new_media_in_ the_social_spaces.pdf?sequence=1

- Yu, C.-H., Wu, J., & Liu, A.-C. (2019). Predicting Learning Outcomes with MOOC Clickstreams. Education Sciences, 9(2), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020104

- Ziemba, E. (2019). The contribution of ICT adoption to the sustainable information society. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 59(2), 116-126. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/08874417.2017.1312635